The Archaeology of a Great Lakes Scow Schooner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004 Institute of the North • U.S. Arctic Research Commission • International Arctic Science Committee Arctic Ocean Marine Routes This map is a general portrayal of the major Arctic marine routes shown from the perspective of Bering Strait looking northward. The official Northern Sea Route encompasses all routes across the Russian Arctic coastal seas from Kara Gate (at the southern tip of Novaya Zemlya) to Bering Strait. The Northwest Passage is the name given to the marine routes between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans along the northern coast of North America that span the straits and sounds of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Three historic polar voyages in the Central Arctic Ocean are indicated: the first surface shop voyage to the North Pole by the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Arktika in August 1977; the tourist voyage of the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Sovetsky Soyuz across the Arctic Ocean in August 1991; and, the historic scientific (Arctic) transect by the polar icebreakers Polar Sea (U.S.) and Louis S. St-Laurent (Canada) during July and August 1994. Shown is the ice edge for 16 September 2004 (near the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice for 2004) as determined by satellite passive microwave sensors. Noted are ice-free coastal seas along the entire Russian Arctic and a large, ice-free area that extends 300 nautical miles north of the Alaskan coast. The ice edge is also shown to have retreated to a position north of Svalbard. The front cover shows the summer minimum extent of Arctic sea ice on 16 September 2002. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service WAV 141990' National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Cobscook Area Coastal Prehistoric Sites_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ' • The Ceramic Period; . -: .'.'. •'• •'- ;'.-/>.?'y^-^:^::^ .='________________________ Suscruehanna Tradition _________________________ C. Geographical Data See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in j£6 CFR Part 8Q^rjd th$-§ecretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. ^"-*^^^ ~^~ I Signature"W"e5rtifying official Maine Historic Preservation O ssion State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this -

1Ba704, a NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE in the MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN and MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION, THE PEOPLE OF AFRICATOWN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY AND THE SLAVE WRECKS PROJECT PREPARED BY SEARCH INC. MAY 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION 468 SOUTH PERRY STREET PO BOX 300900 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 PREPARED BY ______________________________ JAMES P. DELGADO, PHD, RPA SEARCH PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY DEBORAH E. MARX, MA, RPA KYLE LENT, MA, RPA JOSEPH GRINNAN, MA, RPA ALEXANDER J. DECARO, MA, RPA SEARCH INC. WWW.SEARCHINC.COM MAY 2019 SEARCH May 2019 Archaeological Investigations of 1Ba704, A Nineteenth-Century Shipwreck Site in the Mobile River Final Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Between December 12 and 15, 2018, and on January 28, 2019, a SEARCH Inc. (SEARCH) team of archaeologists composed of Joseph Grinnan, MA, Kyle Lent, MA, Deborah Marx, MA, Alexander DeCaro, MA, and Raymond Tubby, MA, and directed by James P. Delgado, PhD, examined and documented 1Ba704, a submerged cultural resource in a section of the Mobile River, in Baldwin County, Alabama. The team conducted current investigation at the request of and under the supervision of Alabama Historical Commission (AHC); Alabama State Archaeologist, Stacye Hathorn of AHC monitored the project. This work builds upon two earlier field projects. The first, in March 2018, assessed the Twelvemile Wreck Site (1Ba694), and the second, in July 2018, was a comprehensive remote-sensing survey and subsequent diver investigations of the east channel of a portion the Mobile River (Delgado et al. -

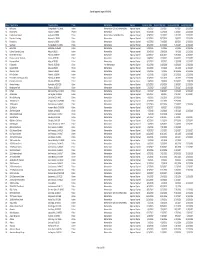

Project-Approval-Log-Condos.Pdf

Condo Approval Log as of 3‐16‐19 State Project Name Project Location Phase Warrantable Decision Expiration Date HOA Cert Exp Date Insurance Exp Date Budget Exp Date AL Bella Luna Orange Beach, AL. 36561 Entire Warrantable ‐ O/O or 2nd Home Only Approval Expired 3/5/2017 2/27/2017 4/7/2017 12/31/2016 AL Brown Crest Auburn, AL 36832 Phase 1 Warrantable Approval Expired 9/24/2016 11/2/2016 2/28/2017 12/31/2016 AL Creekside of Auburn AL, Auburn 36830 Entire Warrantable ‐ Freddie Mac Only Approval Expired 3/28/2017 3/13/2017 11/1/2017 12/31/2017 AL Donahue Crossing Auburn, AL. 36830 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 11/13/2016 10/27/2016 7/4/2017 12/31/2016 AL Residences Auburn, AL 36830 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/15/2016 7/14/2016 8/6/2016 12/31/2016 AL Seachase Orange Beach, AL 36561 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 12/1/2016 11/14/2016 5/23/2017 12/31/2016 AZ Bella Vista Scottsdale, AZ 85260 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/10/2015 9/3/2015 5/9/2016 12/31/2015 AZ Colonial Grande Casitas Mesa, AZ 85211 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 3/14/2018 2/28/2018 7/6/2018 12/31/2018 AZ Desert Breeze Villas Phoenix, AZ 85037 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 11/25/2017 11/21/2017 6/25/2018 12/31/2017 AZ Discovery at the Orchards Peoria, AZ 85381 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 8/8/2017 7/19/2017 8/24/2017 12/31/2017 AZ Eastwood Park Mesa, AZ 85203 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/12/2017 9/7/2017 1/30/2018 12/31/2017 AZ El Segundo Phoenix, AZ 85008 Entire Non‐Warrantable Approval Expired 9/21/2018 8/28/2018 11/8/2018 12/31/2018 AZ Leisure World Mesa, AZ 85206 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 3/11/2018 3/4/2018 1/1/2018 12/31/2017 AZ Mountain Park Phoenix AZ 85020 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 7/13/2015 7/2/2015 11/15/2015 12/31/2015 AZ Palm Gardens Phoenix, AZ 85041 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 7/11/2016 7/5/2016 11/23/2016 12/31/2016 AZ Pointe Resort @ Tapatio Cliffs Phoenix, AZ. -

A Door County Beach in SPRING & EARLY SUMMER

A Door County Beach in SPRING & EARLY SUMMER Discover the four-season beauty of a Lake Michigan beach in Door County, Wisconsin, USA Presented by Glidden Lodge Beach Resort Input from Carolyn Rock, Natural Resource Educator, Whitefish Dunes State Park, Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin “You can tell all you need to about a society from how it treats animals and beaches. Frank Deford All photos taken in May and June of 2012 Ripples of the lake bed can be seen and felt. Formed by wave action, these ripples are small versions of the unique landforms found at the Ridges Sanctuary. Beach chairs near the beach volleyball court offer visitors a view of Lake Michigan as well the competition. An on site spring feeds vegetation around the edges of the beach. Every suite at Glidden Lodge Beach Resort give guests a sunrise view of Lake Michigan. Spring time moss dots the remnants of the Niagra Escarpment. For visitors seeking shade from the hot summer sun, cedar trees on the grounds of Glidden Lodge Beach Resort offer relief. Just down the beach from Glidden Lodge Beach Resort: Whitefish Dunes State Park 4 mile drive or 3.5 mile hike along the beach Shipwreck Australasia Surveying Takes Place At Whitefish Bay Excerpted from Aaron Conklin of the University of Wisconsin, Madison < http://www.news.wisc. edu/20802> At a time when everyone else had switched to iron and steel, James Davidson steadfastly clung to wood, building some of the largest wooden schooners ever to sail the Great Lakes, and becoming a legendary shipbuilding titan in the process. -

JIYC Regatta 2005

JIYC Regatta 2005 June 18 - 19 CLICK FOR A PDF FILE OFF HOBIE COURSE SHEETS Final Results Class Skipper Member Position HOLDER POULNOT 1 HOLDER THOMAS 2 HOLDER BLAIR 3 HOLDER BLAIR 4 HOLDER HAMILTON 5 LASER OREILLY 1 LASER STANGER 2 LASER PACKARD 3 LASER MUHLHAUSEN 4 LASER CALLAHAN 5 LASER LAROCHE 6 LASER BROWN 7 LASER WHITESIDES 8 LASER GOWANS 9 LASER TYNER 10 LASER BYRD 12 LASER GOWANS 13 LASER HAZELTINE 14 LASER GERVAIS 1 RADIAL LASER HAMILL 2 RADIAL LASER SHAPIRO 3 RADIAL LASER SWANSON 4 RADIAL LASER MCKELVEY 5 RADIAL LASER BONNER 6 RADIAL LASER WHITESIDES 7 RADIAL LASER RADIAL REVES C 8 LASER REVES B 9 RADIAL LASER BEAM 9 RADIAL MC SCOW HARKEN 1 MC SCOW MARENAKOS 2 MC SCOW KRAWCHECK 3 MC SCOW SCARBOROUGH 4 MC SCOW LOVIN 5 MC SCOW MOSSMAN 6 MC SCOW PONTIONS 7 MC SCOW DOEHLER 8 MC SCOW HAMMIL 9 MC SCOW NORMAN 10 MC SCOW HAMILTON 11 MC SCOW MILLER 11 SIOD BRYAN 1 SIOD STANGER 2 SIOD MADSEN 3 SIOD HIERS 4 SIOD GRIMBALL 5 SIOD LAROCHE 6 SIOD HAYNSWORTH 7 SNIPE GIBBS 1 SNIPE MUHLHAUSEN 2 SNIPE PALZZO 3 SNIPE BURNS 4 SNIPE SEABROOK 5 MINOR 6 SNIPE MINOR 6 JY15 PARKER 1 JY15 HAGOOD 2 JY15 SMYTHE 3 Class Skipper Member Position E SCOW GRIFFITH 1 E SCOW JORDAN 2 E SCOW WILKINS 3 E SCOW HULL 4 E SCOW PRAUSE 5 E SCOW MARTCHINK 6 E SCOW PERRIN 7 E SCOW ELLYN 8 SUNFISH JR ROHDE 1 SUNFISH JR MCINTOSH 2 SUNFISH JR NETTLES 3 SUNFISH JR ZEIGLER 4 SUNFISH JR MCINTOSH 5 SUNFISH JR HAZELTINE 6 SUNFISH JR WARREN 7 SUNFISH JR BATES 8 SUNFISH JR NETTLES 9 SUNFISH JR BOLAN 10 SUNFISH JR. -

Melges Promo

# THE WORLD LEADER IN PERFORMANCE ONE DESIGN RACING # # MELGES.COM # # MELGES.COM MELGES BOAT WORKS, INC. was founded by Harry C. Melges, Sr. in 1945. Melges became an instant leader in scow boat design, production and delivery in the U.S., particularly in the Midwest. Harry, Sr. initially built boats out of wood. The first boats produced were flat-bottomed row boats, which provided a core business to keep his vision and the company alive. It wasn't long before he branched into race boat production delivering the best hulls, sails, spars, covers and accessories ensuring his customers stayed on the competitive cutting-edge. Melges (pronounced mel•gis), is one of the most reputable, recognized and respected family names in the sailing industry. The devotion, generosity, perseverance and passion that surrounds the name is undeniable. It will forever be a legendary symbol of quality, excellence and experience that is second-to-none. Early on Harry Sr.’s son, Harry “Buddy” Melges, Jr. was involved in operating the family boat building business. Over time, Buddy established an impressive collection of championship titles and Olympic medals. During the 1964 Olympics, Buddy was awarded a bronze medal in the Flying Dutchman and in 1968 won a gold medal at the Pan Am Games. In 1972, he won a gold medal in the Soling in Kiel, Germany — the Soling’s official debut in Olympic competition. In the years that followed, Buddy won over 60 major national and international sailing championship titles. They include the Star in 1978 and 1979; 5.5 Metre in 1967, 1973 and 1983; International 50 Foot World Cup in 1989; Maxi in 1991 and the National E Scows in 1965, 1969, 1978, 1979 and 1983. -

We Paddle the Globe. Current Designs Borrows Its Design Influence and Techniques from Waters Across the Globe

2017 We paddle the globe. Current Designs borrows its design influence and techniques from waters across the globe. Inspired by these purpose-built kayaks and the pioneers that fueled the sport’s innovation, we’ve continued to advance the art through new techniques, materials and technologies. It’s a philosophy born from the idea that it’s not about where you take your kayak – it’s where the kayak takes you. So regardless of the destination, we invite you to begin each journey by exploring our North American, Greenland, British and new Danish style collections, in addition to a range of recreational and specialty models. Each one destined to be “a work of art, made for life” that let’s you take your passion further. 1 Makers OF movement Our international design influence and the visionaries who shape it. Long before the paddle enters the water, New England-based kayak designer Barry each kayak begins with a pen stroke. The Buchanan partnered with us on the famous product of inspiration and experience, hard chine kayak, the Caribou. And later, Nigel Current Designs develops and refines each Foster and CD brought the Greenland-styled model through collaborations with some of Rumor to the world’s waters. The newest the sport’s most celebrated designers and global collaboration can be seen in the Prana craftsmen. These partnerships have become and Sisu models, ushering in our Danish one of the hallmarks of the brand – and collection of kayaks. Celebrated Danish continue to shape its future. kayak designer Jesper Kromann-Andersen Beginning with the flagship Solstice line, has worked with our team to marry classic visionary designers have left their mark hull design with innovative twists for an on the Current Design fleet, while inspiring utra-stylish, remarkably versatile experience an entire generation of paddlers. -

Chapter 3, Historical and Cultural Resources

Door County Comprehensive and Farmland Preservation Plan 2035: Volume II, Resource Report CHAPTER 3: HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCES 16 | Chapter 3: Historical and Cultural Resources Door County Comprehensive and Farmland Preservation Plan 2035: Volume II, Resource Report INTRODUCTION This chapter begins by briefly discussing Door County’s “community character,” which is intertwined with many of the county’s historical and cultural resources. It then provides a brief history of the county’s residents and its development, followed by an inventory of the historical resources in Door County. Included are discussion of the county’s historical associations; the area’s maritime history and maritime museums, lighthouses, and shipwrecks; general museums; archaeological sites; sites on the state and/or federal historic registries; and cemeteries. Finally, this chapter provides an inventory of cultural resources, such as cultural organizations, educational and cultural opportunities, visual and performing arts groups and venues, and festivals. COMMUNITY CHARACTER Community character is defined by a variety of sometimes intangible factors, including the people living in the area, the visual character of the area, and the quality of life and experiences offered to residents and visitors. Door County’s community character was ranked as either the county’s highest or second- highest asset during the public input exercises conducted at the county-wide visioning sessions held between 2006 and 2007. As is evidenced by the lists below of responses from residents at those visioning meetings, all aspects of community character – the people, the visual attributes, and the general quality of life as well as the county’s specific historical and cultural resources – define or exemplify life in Door County. -

Small Boats on a Big Lake: Underwater Archaeological Investigations of Wisconsin’S Trading Fleet 2007-2009

Small Boats on a Big Lake: Underwater Archaeological Investigations of Wisconsin’s Trading Fleet 2007-2009 State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Technical Report Series #10-001 Keith N. Meverden and Tamara L. Thomsen ii Funded by grants from the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, National Sea Grant College Program, and the Wisconsin Department of Transportation’s Transportation Economics Assistance program. This report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, the National Sea Grant College Program, or the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. The Big Bay Sloop was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 14 January 2009. The Schooner Byron was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 20 May 2009. The Green Bay Sloop was listed on the National Register of Historic Places On 18 November 2009. Nominations for the Schooners Gallinipper, Home, and Northerner are pending listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Cover photo: Wisconsin Historical Society archaeologists survey the wreck of the schooner Northerner off Port Washington, Wisconsin. Copyright © 2010 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved iii CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS…………………..………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………….. vii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………. ….. 1 Research Design and Methodology……………………… 3 2. LAKESHORING, TRADING, AND LAKE MICHIGAN MERCHANT SAIL………………………………………….. 5 Sloops…………………………………………………… 7 Schooners……………………………………………….. 8 Merchant Sail on Lake Michigan………………………. 12 3. THE BIG BAY SLOOP……………………………………... 14 The Mackinaw Boat……………………………………. 14 Site Description………………………………………… 16 4. THE GREEN BAY SLOOP………………………………… 26 Site Description………………………………………… 27 5. THE SCHOONER GALLINIPPER ………………………… 35 Site Description………………………………………… 44 6. -

Shipwreck Surveys of the 2018 Field Season

Storms and Strandings, Collisions and Cold: Shipwreck Surveys of the 2018 Field Season Included: Thomas Friant, Selah Chamberlain, Montgomery, Grace Patterson, Advance, I.A. Johnson State Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Technical Report Series #19-001 Tamara L. Thomsen, Caitlin N. Zant and Victoria L. Kiefer Assisted by grant funding from the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute and Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, and a charitable donation from Elizabeth Uihlein of the Uline Corporation, this report was prepared by the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, the National Sea Grant College Program, the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, or the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association. Note: At the time of publication, Thomas Friant and Montgomery sites are pending listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Places. Nomination packets for these shipwreck sites have been prepared and submitted to the Wisconsin State Historic Preservation Office. I.A. Johnson and Advance sites are listed on the State Register of Historic Places pending listing on the National Register of Historic Places, and Selah Chamberlain site is listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places. Grace Patterson site has been determined not eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Cover photo: A diver surveying the scow schooner I.A. Johnson, Sheboygan County, Wisconsin. Copyright © 2019 by Wisconsin Historical Society All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS AND IMAGES ............................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................