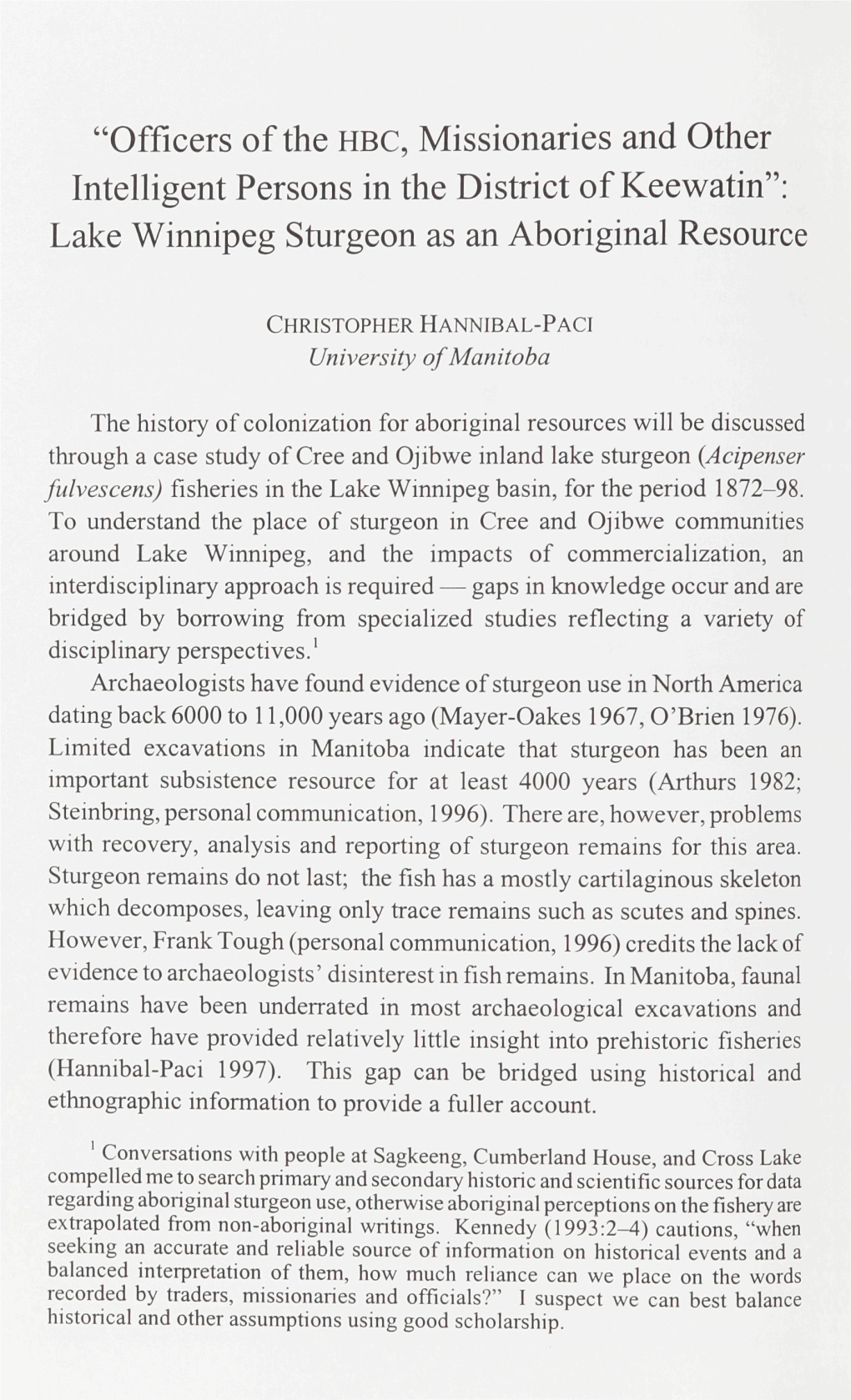

Lake Winnipeg Sturgeon As an Aboriginal Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pimachiowin Aki Annual Report 2020

Annual Report 2020 ON THE COVER Poplar River First Nation students at Pinesewapikung Sagaigan (Weaver Lake), summer 2020 Pimachiowin Aki Corporation Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is a not-for-profit charitable organization with a mandate to coordinate and integrate actions to protect and present the Outstanding Universal Value of an Anishinaabe cultural landscape and global boreal biome. Pimachiowin Aki is a 29,040 km2 World Heritage Site in eastern Manitoba and northwestern Ontario. The site was inscribed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List in 2018. The Corporation is a partnership of the Anishinaabe First Nations of Bloodvein River, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi and Poplar River, and the governments of Manitoba and Ontario. The Corporation’s Vision Pimachiowin Aki is celebrated for its cultural and natural values, and regarded as a model of sustainability. Pimachiowin Aki is an organization that is recognized as a cross-cultural, community-based leader in World Heritage Site management. The Corporation’s Mission To acknowledge and support Anishinaabe culture and safeguard the boreal forest; preserving a living cultural landscape to ensure the well-being of Anishinaabeg and for the benefit and enjoyment of all people. Table of Contents Message from the Co-Chairs ....................................................... 1 Board of Directors and Staff ........................................................ 2 Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site......................................... -

Treaty 5 Treaty 2

Bennett Wasahowakow Lake Cantin Lake Lake Sucker Makwa Lake Lake ! Okeskimunisew . Lake Cantin Lake Bélanger R Bélanger River Ragged Basin Lake Ontario Lake Winnipeg Nanowin River Study Area Legend Hudwin Language Divisi ons Cobham R Lake Cree Mukutawa R. Ojibway Manitoba Ojibway-Cree .! Chachasee R Lake Big Black River Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg Dryden !. !. Kenora !. Lily Pad !.Lake Gorman Lake Mukutawa R. .! Poplar River 16 Wakus .! North Poplar River Lake Mukwa Narrowa Negginan.! .! Slemon Poplarville Lake Poplar Point Poplar River Elliot Lake Marchand Marchand Crk Wendigo Point Poplar River Poplar River Gilchrist Palsen River Lake Lake Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point !. Weaver Lake Charron Opekamank McPhail Crk. Lake Poplar River Bull Lake Wrong Lake Harrop Lake M a n i t o b a Mosey Point M a n i t o b a O n t a r i o O n t a r i o Shallow Leaf R iver Lewis Lake Leaf River South Leaf R Lake McKay Point Eardley Lake Poplar River Lake Winnipeg North Etomami R Morfee Berens River Lake Berens River P a u i n g a s s i Berens River 13 ! Carr-Harris . Lake Etomami R Treaty 5 Berens Berens R Island Pigeon Pawn Bay Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Asinkaanumevatt Pigeon Point .! Kacheposit Horseshoe !. Berens R Kamaskawak Lake Pigeon R !. !. Pauingassi Commissioner Assineweetasataypawin Island First Nation .! Bradburn R. Catfish Point .! Ridley White Beaver R Berens River Catfish .! .! Lake Kettle Falls Fishing .! Lake Windigo Wadhope Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Who opee .! Douglas Harb our Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Little Grand Pigeon River Little Grand Rapids 14 Bradbury R Dogskin River .! Jackhead R a p i d s Viking St. -

Asatiwisipe Aki Management Plan – Poplar River First Nation

May 2011 ASATIWISIPE AKI MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL DRAFT May, 2011 Poplar River First Nation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND SPECIAL THANKS benefit of our community. She has been essential to documenting our history and traditional use and occupancy. The most important acknowledgement goes to our ancestors who loved and cherished this land and cared for it for centuries to ensure all Thanks go to the Province of Manitoba for financial assistance and to future generations would have life. Their wisdom continues to guide us the staff of Manitoba Conservation for their assistance and support. today in our struggles to keep the land in its natural beauty as it was created. We are very grateful to all of our funders and particularly to the Metcalf Foundation for its support and for believing in the importance of a The development and completion of the Asatiwisipe Aki Lands Lands Management Plan for our community. We would also like to thank Management Plan has occurred because of the collective efforts of many. the Canadian Boreal Initiative for their support. Our Elders have been the driving force for guidance, direction and motivation for this project and it is their wisdom, knowledge, and Meegwetch experience that we have captured within the pages of our Plan. Our Steering Committee of Elders, youth, Band staff and Council, and other community members have worked tirelessly to review and provide Poplar River First Nation feedback on the many maps, text and other technical materials that have Land Management Plan Project been produced as part of this process. Community Team Members We, the Anishinabek of Poplar River First Nation, have been fortunate Thanks go to the following people for their time, energy and vision. -

SNC Figure 7-11-Oct09.Mxd

M er u Poplar River 16 r Riv k Wakus opla ut rth P aw No a R Lake Ontario .! . Lake .! Slemon Negginan .! Winnipeg Poplarville Lake Poplar Study Point Area P op la r R Elliot Lake iv er Manitoba Marchand M ar Wendigo Point cha nd Gilchrist Lake Palsen River Lake Cr k Lake Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg !. !. Kenora Dryden !. !. Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point Opekamank !. Weaver Lake Charron ail Crk. McPh Lake P o p la r Bull R iv Lake e r a a Wrong Lake b b o Harrop Lake o Mosey Point i i o o r r t t i i a a t t n Shallow n River f n Lake a n Lea Lewis a Leaf River Sou Lake O O M th M McKay Point Le af P R Eardley Lake o p la r R iv e r i R Lake Winnipeg Etomam North Morfee Lake Project Terminus Station 156+211.731 5799349.082 N 642855.071 E Berens River R Carr-Harris Berens River 13 mi ma Lake Eto Berens B Island e Pigeon re Pawn Bay ns R Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Pigeon Point .! Asinkaanumevatt Kacheposit Horseshoe Be !. Kamaskawak rens R Lake P !. Pauingassi Commissioner ig !. eo Island n Assineweetasataypawin R. R First Nation rn dbu .! Bra Catfish Point .! W B h e i re Catfish te n B s e R Lake a i v v e er r R Fishing Lake Windigo Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Whoopee .! Douglas Harbour Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Pi Little Grand Rapids 14 ge Br o adb n ury R R iv Dogskin River .! Jackhead er St. -

All-Season Road Connecting Berens River to Poplar River First Nation

Project Description Project 4 - All-Season Road Connecting Berens River to Poplar River First Nation Prepared for: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Submitted by: Manitoba Floodway & East Side Road Authority November 2014 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents iii List of Figures v List of Photos v List of Maps vi List of Attachments vi 1 GENERAL INFORMATION AND CONTACTS ............................................................................. 7 1.1 Nature of the Project and Proposed Location .............................................................. 7 1.2 Proponent Information ................................................................................................. 7 1.2.1 Name of the Project ........................................................................................ 7 1.2.2 Name of the Proponent ................................................................................... 8 1.2.3 Address of the Proponent ............................................................................... 8 1.2.4 Chief Executive Officer .................................................................................... 8 1.2.5 Principal Contact Person ................................................................................. 8 1.3 Jurisdictions and Other Parties Consulted .................................................................... 9 1.4 Environmental Assessment Requirements ................................................................. 10 1.4.1 Canadian -

April 2007 from Poplar/Nanowin Rivers Park Reserve To: Poplar River First Nation Asatiwisipe Aki Protected Lands

BRIEF: April 2007 From Poplar/Nanowin Rivers Park Reserve to: Poplar River First Nation Asatiwisipe Aki Protected Lands • The Poplar/Nanowin Rivers Protected Area covers 777,270 ha (1,920,680 acres) of Manitoba Boreal forest lands and waters on the east side of the province, near the top of the eastern shore of Lake Winnipeg • As part of Manitoba’s Boreal regions (2/3 of the province) the dominant landscape feature within the Protected Area is stands of spruce, pine, tamarack and fir. Muskeg (a mat of sphagnum moss and water), peat bogs, rivers, cold lakes and wetlands abound. • Lake Winnipeg provides the western border of the Protected Area – important as the fifth-largest freshwater Lake in Canada and 10th in the world • The lands within the Poplar/Nanowin Rivers Protected Area are an example of an intact Boreal ecosystem where natural processes such as fire, wind and insects plus climate determine species’ cycles as well as functions of the boreal ecosystem. Due to large size and intactness, the boreal forest here provides ecological services that benefit Poplar River First Nation members, Manitobans and the world: . clean water through water filtration . clean air through oxygen production . rebuilding of soils and restoration of nutrients . holding back floodwaters and releasing needed water into rivers and streams . carbon storage through absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the soil, trees, and water systems . maintaining biodiversity by providing habitat for countless species • Logging, mining, and development of oil, petroleum, natural gas or hydro-electric resources are legally prohibited within protected areas in Manitoba, as are activities that risk significant impacts on habitat. -

UN-GGIM Country Report of Canada 2018

UNITED NATIONS STATISTICS DIVISION Country Report of 2018 Prepared by: Canada Centre for Mapping and Earth Observation, Natural Resources Canada Table of Contents Country Report Overview ............................................................................................................. i I. Introduction: Canada’s Political Landscape and Policy Priorities ............................... 1 II. Canada’s International Responsibilities and Activities in Geomatics ........................... 6 III. Canadian Spatial Data Infrastructure ............................................................................. 8 IV. Collaborative SDI Initiatives: ......................................................................................... 11 Arctic Spatial Data Infrastructure ............................................................................................. 11 Marine Spatial Data Infrastructure ............................................................................................ 13 Spatial Data Infrastructure Manual for the Americas ............................................................... 15 Open Geospatial Consortium .................................................................................................... 15 Canadian Council on Geomatics ............................................................................................... 17 GeoBase .................................................................................................................................... 17 Geographical Names Board -

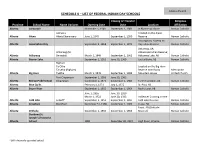

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Community Sharing Circle Briefing Note: Poplar River First Nation

Community Sharing Circle Briefing Note Poplar River First Nation, Manitoba Briefing Note of IISD’s Natural and Social Capital Program and the IISD Foresight Group October 2011 Purpose and Context of the Sharing Circle An interactive sharing circle-style workshop was held in Poplar River on March 22, 2011 to explore a series of questions to better understand how the local environment helps maintain and improve the well-being of First Nations peoples living in remote communities. The sharing circle also discussed observed changes in the local environment and how the community might possibly cope with and adapt to future environmental changes related to climate variability and change. The sharing circle was facilitated by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). The insights compiled serve several purposes, including informing local planning efforts and the Pimachawin Aki’s proposal for World Heritage Site status. IISD will also harness the insights to help advance practical terminology for communicating to policy-makers the important linkages between human well-being and the variety of services provided by the environment. About Poplar River First Nation Poplar River First Nation is located on the east side of Lake Winnipeg at the mouth of the Poplar River, approximately 340 km north of Winnipeg. Their traditional territory consists of the Poplar River/Nanowin Park Reserve, which covers a surface area of approximately 7,773 km2 and is located entirely in Manitoba. There are no outstanding treaty land entitlements on their land. The Poplar River First Nation has a registered population of 1,606 people as of August 2011, with 1,210 living on the reserve.1 Of the total population, 400 people declared being in the labour force, working mostly in the services sector (health care, social services, educational services, government services, sales) with the rest of the employment in the trades, primary and processing industries (transport, manufacturing, utilities, equipment operators and related occupations). -

Linguistic Vitality in Manitoba

Linguistic Vitality in Manitoba A survey of language, health, and wellbeing in a northern Ojibwa community Stephen Kesselman University of Manitoba Poplar River First Nation Azaadiwi-ziibi Nitam-Anishinaabe o The People and Language • ~ 1200 residents • Majority Ojibwa, some Metis Nation • Ojibwe Continuum • Northwestern, Anishinaabemowin – EGIDS 7 ‘shifting’ o The Land and Community • Sophia Rabliauaskas • Pimachiowin Aki -The Land that gives Life world heritage project Poplar River First Nation (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Anishinaabewaki.jpg) Poplar River language survey project Motivating questions: What?, How?, and Why? of describing linguistic health • What is guiding this description? - Limits of LVE and EGIDS - modified framework adapted from LVE • How is it being done? - Survey method, ‘bottom-up’ approach • Why are we doing it? 1. Describe the vitality of Ojibwe in PRFN from the eyes of those who live there. 2. Consider linguistic vitality in terms of determinants of health Our Framework A re-envisioning of LVE Removes: Factors of Vitality • Documentation 1 Intergenerationality Consolidates: 2 Number of Speakers • Numbers – total and proportional • Attitudes – community and official 3 Domains and Functions • Domains – all domains 4 Attitudes and Beliefs Redefines: 5 Access to Educational Materials • Materials Adds: 6 Programs • Programs – Ongoing and planned 7 Language Knowledge • Knowledge – compared to self-reports and relative to age-groups and total numbers The Survey Questionnaire design and target factors o 4 Sections Vitality Factor # of relevant 1. Background questions 2. Attitudes and Beliefs 1 Attitudes and Beliefs 14 3. Ojibway in the Community 2 Domains and Functions 9 4. Language Knowledge 3 Knowledge 9 o Questions specific to target factors 4 Intergenerationality 8 5 Number of Speakers 5 o Factors represented proportionately 6 Programs 4 to their relevance, for our purposes 7 Access to Materials 2 The Survey Questions – targeting factors e.g. -

The Importance of Non-Anonymous Birds

Jim Duncan A young The Importance of Barred Owl chick, recently Non-anonymous Birds fledged and about to be Encounters with Banded Owls banded. by Jim Duncan, Manager of the Biodiversity and Endangered Species Section, Manitoba Conservation housands of birds pass through our lives but sometimes a particular individual bird leaves its mark Ton us – like the Ruffed Grouse ‘George’ that stalked my wife and family in our yard for over 8 months. Many of us want to think (or are even convinced) that ‘our pair’ of robins has returned to our home garden. Occasionally a unique feature, such as a raspy atypical song or an injury (such as the one-legged female Red-winged his practice requires Blackbird encountered “T considerable effort, over many years by Bob and is undertaken under Nero in Charleswood), permit and with strict confirms our suspicion. In the world of scientific animal care guidelines...” literature however, anecdotal speculation about the identification of individual birds and their associated biology are routinely and ruthlessly eliminated by editors with thick red pens. Thus to expound any facts or theories on individual birds in such IN THIS ISSUE... venues requires more extreme methods – capturing birds and applying Canadian Wildlife Service bands. The Importance of Non-anonymous Birds .... p. 1 & 5 President’s Corner ..................................... p. 2 & 16 My wife Patsy, a biologist, and I have been banding Great Gray Owls and other owl species in Manitoba for over 25 Member Profile: John Gray ................................p. 3 years, along with colleagues such as Herb Copland, Bob BIG TREES, Little Trees ........................................p. -

FIVE THINGS the Federal Government Must Do for Lake Winnipeg

FIVE THINGS THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT MUST DO FOR LAKE WINNIPEG Hecla Island; Photo: Paul Mutch Paul Photo: Island; Hecla FOREWORD Lake Winnipeg has been a lifeline for the people of all our communities who have lived on the lake for thousands of years. We have shared the good gifts of fresh fish, waterfowl and other aquatic life which have provided sustenance for our families. Our communities have also shared the responsibility to care for the lake and all its life. As Anishinaabe, we have always tried to follow the laws and teachings given to us from our Creator on how to respect and care for all life. For many years now, these laws and teachings have been dominated by a different set of laws, and the lake is suffering. There has been a complete lack of respect for the spirit and life of the lake. - Sophia Rabliauskas KNOWLEDGE HOLDER, POPLAR RIVER FIRST NATION 2 | LAKE WINNIPEG INDIGENOUS COLLECTIVE | LWIC.ORG FIVE THINGS the federal government must do for Lake Winnipeg 1. Recognize phosphorus as the cause of blue-green algal blooms on Lake Winnipeg 1.1 Accept the International Joint Commission’s recommendation of an annual phosphorus- 8 loading target for the Red River to combat the eutrophication of Lake Winnipeg. Request further evidence to justify the proposed nitrogen-loading target. PAGE 1.2 Set limits for phosphorus in sewage effluent within updated Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations under the renewed Fisheries Act. 2. Use evidence to guarantee impact from every federal government dollar spent to reduce phosphorus loading to Lake Winnipeg 2.1 Renew the Lake Winnipeg Basin Program in Budget 2022.