DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 254 SE 014 529 AUTHOR Stocklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

YWEIGNITE /Youngwomenempowered @Youngwomenempowered Tonight's Program

#YWEIGNITE /youngwomenempowered @youngwomenempowered tonight's program 6:00pm - Cocktail Reception Raffles Wine Toss Feed the Fire Photo Booth - sponsored by Seattle Party Shots Y-WE Ignite Passport The first 20 to complete their passport take home a piece of Y-WE’s heart! 7:30pm - Dinner Program Video: Dreams Take Flight Emcee Welcome: Sonja Lerner & Adanech Muno Co-Directors Welcome: Jamie-Rose Edwards & Victoria Santos Table Talks Spoken Word Performance: Suhur Ahmed & Nikai Mackie Live Auction Keynote: Aisha Al-Amin Raise Your Heart for Y-WE Raffle Winners Announced (must be present to win) Musical Performance: Beatriz Angel-Ramos, Prisca Denis, Carla Ferrazzi, Miles King & Sophie Theriault We extend our deepest gratitude to tonight’s brave and inspiring youth performers. As a show of respect and love, please do not chat at your tables when our world-changing leaders take the stage. (Trust us, you won’t want to miss a second of their powerful performances!) Special thanks to Kamilla Kafiyeva & McKain Lakey, Y-WE Teaching Artists thank you for attending ignite 2018 Tonight’s Video Made Possible by: Suzanne Hayward Michael B. Maine Producer & Y-WE Board Member Photographer Richard Hemmingway Justen Van Dyke Editor Videographer #YWEIGNITE /youngwomenempowered @youngwomenempowered Y-WE empowers young aboutwomen from us diverse backgrounds to step up as leaders in their schools, communities, and the world. We do this through intergenerational mentorship, intercultural collaboration, and creative programs that equip girls with the confidence, resiliency, and leadership skills needed to achieve their goals and improve their communities. For more information, please visit www.y-we.org. -

Notice and Agenda Special Council Meeting CALL to ORDER

Notice and Agenda Special Council Meeting Public Notice is hereby given of a Special Council Meeting duly called in accordance with Section 126 of the Community Charter, to be held on: Date: Tuesday, May 20, 2014 Time: 4:00 p.m. Place: Anderson Room Richmond City Hall 6911 No. 3 Road Public Notice is also hereby given that this meeting may be conducted by electronic means and that the public may hear the proceedings of this meeting at the time, date and place specified above. The purpose of the meeting is to consider the following: CALL TO ORDER RECESS FOR OPEN GENERAL PURPOSES COMMITTEE **************************** RECONVENE FOLLOWING OPEN GENERAL PURPOSES COMMITTEE RICHMOND OLYMPIC OVAL CORPORATION 1. UNANIMOUS CONSENT RESOLUTIONS OF THE SHAREHOLDER OF RICHMOND OLYMPIC OVAL CORPORATION (File Ref. No.: 06-2050-20-ROO) (REDMS No. 4232131) CNCL-5 See Page CNCL-5 for AGM Material CNCL-30 See Page CNCL-30 for ROO 2013 Annual Report CNCL – 1 (Special) 4221360 Special Council Agenda Tuesday, May 20, 2014 RESOLVED THAT: (1) the Shareholder acknowledges and confirms the previous receipt of financial statements of the Company for the period from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2013, together with the auditor’s report on such financial statements, which financial statements were approved by the Company’s board of directors on April 23, 2014 and presented to the Shareholder at the Finance Committee meeting of Richmond City Council on May 5, 2014; (2) the shareholder acknowledges that the following directors are currently serving a 2 year term and -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 15} Research completed as of August 1, 2014 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) Team: Arizona Scorpions Principal Owner: Tris Tilley Team Website Arena: Glendale Community College Team: Atlanta Aliens Principal Owner: Adrian Provost Team Website Arena: Jefferson Basketball Stadium Team: Atlanta Wildcats Principal Owner: William D. Payton IV Team Website Arena: Henry County High School Team: Austin Boom Principal Owner: C&J Elite Sports LLC Team Website Arena: N/A © Copyright 2014, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Bay Area Matrix Principal Owner: Jim Beresford Team Website Arena: Diablo Valley College Team: Birmingham Blitz Principal Owner: Birmingham Blitz LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: Bill Harris Arena Team: Bowling Green Bandits Principal Owner: Matt Morris Team Website Arena: N/A Team: Calgary Crush Principal Owner: Salman Rashidian Team Website Arena: SAIT Polytechnic Team: Central Texas Swarm Principal Owner: Swarm Investment Group/ Shooting Stars Sports & Entertainment Team Website: N/A Arena: N/A Team: Central Valley Titans Principal Owner: Josh England Team Website: N/A Arena: Exeter Union High School © Copyright 2014, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 2 Team: Chicago Court Kingz Principal Owner: Unique Starz Sports & Entertainment Team Website Arena: N/A Team: Chicago Steam Principal Owner: Ron Hicks Team Website Arena: South Suburban College Team: Colorado Cougars Principal Owner: Patrick Kelly Team Website Arena: Loveland High School Team: Colorado Kings Principal Owner: Durrell Middleton Team Website Arena: Overland High School Team: Columbus Life Bearcats Principal Owner: Terence Coley Team Website: N/A Arena: Carver High School Update: In June 2013, Columbus Life Tigers and Georgia Bearcats merged to make the Columbus Life Bearcats. -

Seattle Terminal Radar Approach Control

Seattle Terminal Radar Approach Control TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to Seattle TRACON 3 Seattle TRACON Today 4 Seattle TRACON Leadership Team 6 Our Expectations of All Employees 10 Policies 11 Local Area Information 13 Restaurants of Note 16 Online Resources 18 Seattle TRACON Directory 22 2 Welcome to Seattle TRACON On behalf of everyone here, I am pleased and honored to have this opportunity to welcome you. Here you will have an opportunity to work with an outstanding team of professionals that help make this a great place to work and develop your skills. We are delighted that you will be joining us. We are very proud of our facility. This is an exciting area to live and work in. We have one of the newest and most unique TRACONs ever built. We are committed to a high standard of excellence and are very proud of the professional air traffic services that we provide within the Western Washington State area. The pages that follow include some information about the TRACON, management and staff. In this package we are also including information on the local area to help you familiarize yourself with the area. Once you report to the TRACON you will have ample time to study during the classroom portion of your training program. The training department has put together some information if you wish to familiarize yourself in advance. All of us want to make your tenure at this TRACON as enjoyable and rewarding as possible. Please feel free to ask any questions and express your thoughts and ideas to the staff and senior leadership. -

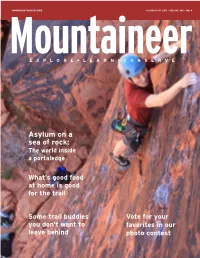

Asylum on a Sea of Rock: the World Inside a Portaledge

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG JULY/AUGUST 2011 • VOLUME 105 • NO. 4 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E Asylum on a sea of rock: The world inside a portaledge What’s good food at home is good for the trail Some trail buddies Vote for your you don’t want to favorites in our leave behind photo contest inside July/Aug 2011 » Volume 105 » Number 4 11 These are your true trail buddies Enriching the community by helping people Don’t forget your electrolyte and hydration partners explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest. 15 A vacation for you, a plus for trails The many benefits of summer trail-work vacations 11 17 Good trail food starts at home Dehydrating your own meals for the hills 21 Living large on the portaledge Kitchen, cot, kite, refuge: life on a portaledge 24 Photo contest semifinalists Vote for the winners! 4 I’M WHERE? Trail companions that will stand by you Guess the location in the photo 21 7 conservation currents News about conservation and recreational access 9 reaching OUT Connecting the community to the outdoors 12 playground Outdoor puzzles for the young Mountaineers 13 CLIffnotes Life on the ledge The latest from the climbing world 14 steppING Up 24 For Helen Engle, stewardship comes naturally 19 OUR fRIENdS American Alps Challenge in North Cascades 32 branching OUT News from branch to branch Photo contest semifinals 37 GO GUIdE Trips, outings, events, courses, seminars The Mountaineer uses . -

Live Auction Catalog

Welcome Good Evening! On behalf of Board members and staff of the Boys & Girls Clubs of Snohomish County, I would like to welcome you to our Grand Gala. Tonight I would like to ask you to join me in celebrating and giving recognition to the staff, volunteers, and contributing members of our clubs. Through our 17 clubs we provided services to over 16,000 kids last year. Even though we are all facing an uncertain and challenging economy, our team has succeeded in expanding support for an ever increasing number of kids in need. Our clubs don’t get a lot of attention. They are located for service, not for visibility. They quietly provide a safe place for kids. They offer daycare services and they feed many children that would not otherwise get the food and nutrition they need. Kids in our clubs will be found doing homework, making friends, playing sports and games, and being mentored and guided by positive role models. Our clubs build futures and create opportunity where opportunities are rare and futures dim. We do great things, but we need your support. Tonight you have the opportunity to invest in our kids. Your investment will be used to build the very foundation of the future of our community: our youth. As a stockholder you will receive regular dividends: safe kids; healthy, nourished children; kids ready and able to learn; young adults with opportunity and prepared for success. I hope you have a very enjoyable evening and I would like to thank you in advance for your generosity and sacrifice, and for joining me in investing in our kids, our community, and our future. -

GOOD for YOU, GOOD for YOUR COMMUNITY Learn, Serve, and Train in the National Guard You’Ve Seen the Images

GOOD FOR YOU, GOOD FOR YOUR COMMUNITY Learn, Serve, and Train in the National Guard You’ve seen the images. A community is in ruins after a disaster and the Army National Guard rolls in to help. Now imagine it’s your community. Imagine it’s you rebuilding a community’s dreams. - Train and Serve Close to Home - Respond to Domestic Emergencies - Serve Part-time in Your Community - Education Benefits SERVE YOUR COMMUNITY AND BUILD YOUR FUTURE IN THE ARMY NATIONAL GUARD VISIT: GoWaGuard.com NORTHWEST ATHLETIC CONFERENCE 2016 NWAC Clark College, TBG 121 BASKETBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS 1933 Fort Vancouver Way Vancouver, WA 98663-3598 PHONE (360) 992-2833 ADVERTISING SALES (360) 992-2777 E-MAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.nwacsports.org March 10-13, 2016 NWAC STAFF Executive Director Marco Azurdia Everett Community College, Everett, WA Executive Assistant Carol Hardin Compliance Manager Jim Jackson Director of Operations Garet Studer Sports Information Director Tracy Swisher Live Webcasts: Sports Information Assistant Spencer Roland https://www.youtube.com/c/NWACSportsNetwork NWAC EXECUTIVE BOARD North: Rusty Wire, Bellevue North: Jorge de la Torre, Edmonds East: Ken Burrus, Spokane PROGRAM DIRECTORY East: Cheryl Holden, Columbia Basin West: Shelley Bannish, Centralia 6-7 MEN’S & WOMEN’S TEAM STATISTICS West: Duncan Stevenson, Pierce (Chair) 8-9 MEN & WOMEN’S LEADERS South: Dick Magruder, Portland 11 PAST CHAMPIONS South: Jayme Frazier, Linn-Benton 13 MEN & WOMEN’ BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT TOTALS 13 MEN’S STANDINGS, WOMEN’S STANDINGS Presidents Washington: -

IBL Releases Yamhill Highflyers 2010 Schedule

For immediate release: Portland, Oregon November 4, 2009 2:00PM Pacific Coast Time News story written by: IBL Commissioner Mikal Duilio Contact: 866IBLGAME or [email protected] INTERNATIONAL BASKETBALL LEAGUE RELEASES 2010 SCHEDULE FOR THE YAMHILL HIGHFLYERS Portland, Oregon—the International Basketball League announces the 2010 IBL schedule for the Yamhill Highflyers. The Highflyers will play their home games in Yamhill County particularly with games in Newberg and McMinnville (official venues to be announced). The schedule was released to the owner a few weeks ago and released publicly today—six months in advance of the team’s first home game. About the team last year/2009: in 2009, the team was in a ‘coming soon’ mode that the IBL uses to get teams ready for a full entry; in that year, the Yamhill Highflyers played 2 home games and 8 away games. The star of the team was supposed to be Chris Hunt—and he ended up truly being that star player. Hunt averaged 14.6 points per game and 8.4 rebounds/per game in 26 IBL games overall (he played for the Hotshots of Central Oregon when not involved in the Highflyers season) but more impressive were the huge numbers he put up while with the Highflyers; it is expected that Chris Hunt will return as the team’s captain in 2010. About the team this year/2010: the Highflyers will be a full 22game team so they will be a better team—more competitive as the overseas players who comprise most teams in the International Basketball League typically want to play for a full season (full season of stats—20 to 22 games, full season of workouts, etc.). -

1956 , the Mountaineer Organized 1906 • Incorporated 1913

The M_ 0 U NTA I N E E R SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 1906 CJifty Qoulen Years of ctl([ountaineering 1956 , The Mountaineer Organized 1906 • Incorporated 1913 Volume 50 December 28, 1956 Number 1 Boa KOEHLER Editor in Chief MORDA SLAUSON Assistant Editor MARJORIE WILSON Assistant Editor SHIRLEY EASTMAN Editorial Assistant JOAN ASTELL Everett Branch Editor BRUNI WISLICENUS Tacoma Branch Editor IRENE HINKLE Membership Editor I,, � Credits: Robert N. Latz, J climbing adviser; Mrs. Irving Gavett, clubroom custodian (engravings) ; Elenor Bus well, membership; Nicole Desme, advertising. Published monthly, January to November· inclusive, and semi monthly during December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc., P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. (Clubrooms, 523 Pike St., Se attle.) Subscription Price: $2 yearly. Entered as second class matter, April 18, 1922, at Post Of fice in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright 1956 by THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc. Photo: Shadow Creek Falls by Antonio Gamero. Confents I E A FoR.WORD-hy Paul W. Wiseman__________________________________________________________________________ 5 History" 1906 THE FrnsT TwE 'TY-YEARS 1930-by Joseph T. H<izard_ ________________:____________________ 6 1931 THESECOND TwE 'TY-FIVE YEARS 1956-by Arthur R. Winder________________________ 14 1909 THE EvERETT BRANCH 1956-by Joan Astell ------------------------------------------------- 21 1912 THE TACOMA BRANCH 1956-by Keith D. Goodman---------------------------------------- 23 A WORD PORTRAIT OF EDMONDS. MEA 'Y-by Lydia Love,·ing Forsyth ______________________ 26 MEANY: A PoEM-by A. H. Albertson ..------------------ --------------------------------------------------- 32 FLEETING GLIMP ES OF EDMOND S. MEANY-by Ben C. Mooers------------------------------ 33 FrnsT SUMMER OUTING: THE OLYMPICS, 1907-by L. A. Nelson-----------------�--------- 34 EARLY Oun Gs THROUGH THE EYES OF A GIRL-by Mollie Leckenby King------------ 36 JOHN Mum's AscE T OF MOUNT RAINIER (AS RECORDED BY HIS PHOTOGRAPHER A. -

EAGLES 3RD ANNUAL HALL of FAME BENEFIT AUCTION CATALOG Friday, March 22, 2013 Silent Auction Items: White Bidding Closes on All Items in This Section at 6:10 Pm

Honoring Our EAGLES 3RD ANNUAL HALL OF FAME BENEFIT AUCTION CATALOG Friday, March 22, 2013 Silent Auction Items: White Bidding closes on all items in this section at 6:10 pm. Item #101 ACROPOLIS GIFT CARD VALUE: $40 Enjoy a night out at Acropolis Pizza & Pasta in downtown Kirkland for some of the best sandwich grinders in town. Happy Acropolis Item #102 BAYMONT INN & SUITES GETAWAY WITH CAFE VELOCE GIFT CARD VALUE: $165 Great for a birthday, anniversary, weekend getaway, or anything else you can think of. Leave the kids at home and enjoy a one-night stay at the Baymont Inn & Suites in their King bedroom suite including whirlpool. Also included is a great Italian dinner just around the corner at Café Veloce, which offers some of the best Italian food with one of the most unique and special Italian dining experiences. Evening Schedule Café Veloce is a family-owned business decorated in vintage Italian racing styles. Baymont Inn & Suits and Cafe Veloce 5:00 PM– REGISTRATION & SILENT AUCTION OPENS Item #103 SILENT AUCTION CLOSING SCHEDULE PAMPER YOURSELF WITH A NEW HAIRCUT 6:10 pm – White Section AND COFFEE DOWNTOWN KIRKLAND VALUE: $70 This package includes a $45 gift card for a women’s haircut at Haute Philosophy 6:30 pm – Blue Section Salon in downtown Kirkland, as well as a $25 gift card to Café Ladro to either pop 6:50 pm – Gold Section in for a relaxing cup of coffee just a block from the salon, or any of the other 15 Café Ladro locations in the Seattle area. -

2019-2020 Annual Report

LAND FOR GOOD EVERGREEN CARBON CAPTURE 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT A MESSAGE FROM OUR CEO Earlier this year, I planted trees alongside hundreds of volunteers on the banks of the Green-Duwamish River. The cold bit at our cheeks. Soil squeezed under our fingernails. The air carried a festive energy as we worked together to tackle climate change. When we left, the banks were filled with Western redcedars and firs ready to offset carbon emissions. This past season was the strongest yet for Forterra’s Evergreen Carbon Capture program. Families, individuals, and over 30 businesses planted 6,000 trees to address their carbon footprints. Our nine field partners and 300 volunteers worked together across 11 sites in the Puget Sound region to plant trees. Together, we are addressing our global climate crisis, restoring our local forests, and cleaning the air for our region. The trees we plant today will be around for generations to come. Thank you for your generosity and commitment to making this a better place for all of us. Michelle Connor President & CEO Forterra PHOTOS: MIKE FIECHTNER President & CEO Michelle Connor plants Western redcedar Forterra AmeriCorps member Fate Syewoangnuan with Seattle Sounders FC near the Duwamish River. provides instructions to ECC planting volunteers. EVERGREEN CARBON CAPTURE 2019- BY THE NUMBERS 2020 30 300 6,000 CORPORATE & NONPROFIT TREE-PLANTING TREES PLANTED THROUGHOUT PARTNERS VOLUNTEERS THE PUGET SOUND 11 9 30,000 TREE-PLANTING FIELD PARTNER TONS OF C02e SITES ORGANIZATIONS SEQUESTERED* * ASSUMING 100-YEAR AVERAGE LIFESPAN FOR TREES PLANTED CLEANING UP CARBON FOOTPRINTS BY PLANTING TREES Over the past year, Forterra’s Evergreen Carbon Capture (ECC) program added some 6,000 more trees to local forests, building climate resilience and restoring the ecological function of our urban green spaces and forested lands.