Seatle Parks and Recreation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks and Recreation

PARKS AND RECREATION Parks and Recreation Overview of Facilities and Programs The Department of Parks and Recreation manages 400 parks and open areas in its approximately 6,200 acres of property throughout the City, works with the public to be good stewards of the park system, and provides safe and welcoming opportunities for the public to play, learn, contemplate, and build community. The park system comprises about 10% of the City’s land area; it includes 485 buildings, 224 parks, 185 athletic fields, 122 children's play areas, 24 community centers, 151 outdoor tennis courts, 22 miles of boulevards, an indoor tennis center, two outdoor and eight indoor swimming pools, four golf courses, studios, boat ramps, moorage, fishing piers, trails, camps, viewpoints and open spaces, a rock climbing site, a conservatory, a classical Japanese garden, and a waterfront aquarium. The development of this system is guided by the Seattle Parks & Recreation Plan 2000, the 38 neighborhood plans, the Joint Athletic Facilities Development Program with the Seattle School District, the 1999 Seattle Center and Community Centers Levy, the 2000 Parks Levy, and DPR’s annual update to the Major Maintenance Plan. 2000 Parks Levy In November 2000, Seattle voters approved a $198.2 million levy lid lift for Parks and Recreation. The levy closely follows the plan forged by the Pro Parks 2000 Citizens Planning Committee. The levy is designed to fund more than 100 projects to improve maintenance and enhance programming of existing parks, including the Woodland Park Zoo; acquire, develop and maintain new neighborhood parks, green spaces, playfields, trails and boulevards; and add out-of-school and senior activities. -

The Groupon Bite of Seattle®, July 15-17 at Seattle Center, Is A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Megan Postiglione July 11, 2016 Festivals Inc. (425) 295-3262 [email protected] THIS WEEKEND: Catch a Ride to the Groupon Bite of Seattle® The Groupon Bite of Seattle®, July 15-17 at Seattle Center, is a summer favorite! The Bite celebrates its 35th Anniversary this year and features 60+ restaurants and vendors, local Craft Beer and Cider Tasting, all-new The Wine Bar and Craft Courtyard, 5 music & entertainment stages, a free movie night on Friday, July 15th at 8:30pm featuring Jurassic World, Beer Gardens featuring both local craft beer and local spirits signature cocktails, local chefs performing live cooking demonstrations and mystery ingredient cook-offs on stage, a Family Fun stage, Sponsor tours & samples, and much more! With so much going on guests should plan for crowded streets as high attendance is anticipated for the 2016 festival. These transportation tips can help you save time, gas and some very sore feet! PLAN AHEAD The Groupon Bite of Seattle® is located at Seattle Center in the Uptown neighborhood (Street address is 305 Harrison St. Seattle, WA 98109). Allow time to drive to the Center, park and maneuver through the crowds. Arriving early will ensure that you don’t miss out on any of the Bite events! Information on current road construction may be found here: http://www.seattlecenter.com/news/detail.aspx?id=1609 USE METRO SERVICE It is easy to navigate Seattle’s transit system with Metro’s Trip Planner, and you can plan your trip to Seattle Center from anywhere in the region. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 254 SE 014 529 AUTHOR Stocklin

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 254 SE 014 529 AUTHOR Stocklin, William J. TITLE What's It All About? Survival Through Education. A Proposal for the Creation and Implementation of Environmental Education in the Northwest Region of Washington State. INSTITUTION Northwest Environmental Education Center, Bellingham, Wash. PUB DATE Oct 70 NOTE 185p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Community Programs; Cooperative Programs; County Programs; *Environmental Education; *Program Development; *Project Applications; Regional Programs; *Staff Improvement IDENTIFIERS Northwest Environmental Education Center ABSTRACT A request for the creation and implementation of environmental education in the northwest region of Washington state is prepared in this project proposal. Designed as a model to aid in the development of a state plan for environmental education, this interdisciplinary, field- and people-oriented project of the Northwest Environmental Education Center plans to establish model/pilot projects throughout the region. Implementation is by a three-phase plan. The first, at the community level, establishes a pilot program in the SedrorWoolley school district aimed at staff improvement and development, development of curriculum learning packages, field program implementation, and disseminating information about the program. The second phase proposes a two-part study with the Watcom County Park Board and schools participating to develop a county-wide model for the implementation of environmental education in the schools. A county environmental analysis project will be undertaken with the findings used in school program development. Regional applications compose the third phase and constitute a major portion of the document. The Whidbey Island site is to be utilizedas a regional center for staff improvement and development, operating a program which will provide school districts with a hierarchy of environmental education specialists. -

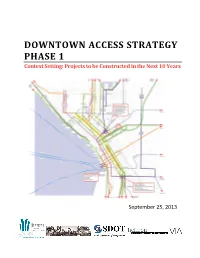

Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to Be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents

DOWNTOWN ACCESS STRATEGY PHASE 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 II. Review of Existing Plans, Projects, and Programs ......................................... 2 III. Potential Construction Concerns and Opportunities .................................. 3 A. Existing Construction Planning Tools 3 B. SDOT’s Construction Hub Coordination Program 4 C. Construction Mitigation Strategies Used by Other Cities 7 D. Potential Construction Conflicts and Opportunities 10 IV. Future Transportation Network Opportunities ......................................... 12 A. North Downtown 12 B. Denny Triangle / Westlake Hub 14 C. Pioneer Square / Chinatown-ID 15 D. Downtown Core and Waterfront 16 V. Future Phases of Downtown Access Strategy ............................................. 18 A. Framework for Phase 2 (2014 through 2016) 18 B. Framework for Phase 3 (Beyond 2016) 19 - i - September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years I. INTRODUCTION Many important and long planned transportation and development projects are scheduled for con- struction in Downtown Seattle in the coming years. While these investments are essential to support economic development and job growth and to enhance Downtown’s stature as the region’s premier location to live, work, shop and play, in the short-term they present complicated challenges for con- venient and reliable access to and through Downtown. The Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) and its partners, Historic South Downtown (HSD) and the Seat- tle Department of Transportation (SDOT), seek to ensure that Downtown Seattle survives and prospers during the extraordinarily high level of construction activity that will occur in the coming years. -

![King County Metro Schedule [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2992/king-county-metro-schedule-pdf-452992.webp)

King County Metro Schedule [PDF]

Route 62 Snow Shuttle continues 62 WEEKDAY/Entre semana 62 WEEKDAY/Entre semana north to NE 125th To DOWNTOWN SEATTLE ➜ To SAND POINT ➜ 5 St, then east to S Sand Green S Lake S Lake Green Sand N Sand Point Wy NE. an d Point Lake Wallingford Union Downtown Seattle Downtown Seattle Union Wallingford Lake Point P E e on Sand Pt Way NE 65th St NE Ravenna Blvd Stone Way N Dexter Ave N 3rd Ave S Washington St S Jackson St 3rd Ave Dexter Ave N N 45th St NE Ravenna Blvd NE 65th St Sand Point Way i i N 75 45 ev 26 vNE GREEN LAKE ROOSEVELT t NE & & & & & & & &&&&&&NE & A NE 74th St W COMM CTR HS VIEW h A T yN MAGNUSON T t52 NE 74th St 35th Ave NE 68th Ave NE N 45th St Harrison St Union St 4th Ave S 5th Ave S Union St Mercer St Stone Way N NE 68th St 35th Ave NE NE 74th St Green 65 PARK t5 RIDGE Lake NE 68th St E Stop #10640 Stop #37940 Stop #16515 Stop #7350 Stop #18390 Stop #450 Stop #625 Stop #1530 Stop #570 Stop #18465 Stop #29231 Stop #16400 Stop #37460 Stop #10640 1h NE 65th St NE Wy n T T SAND N y — — 4:56 5:05 5:20 5:27‡ 5:32‡ 5:34 5:40 5:48 5:59 6:06 6:14‡ 6:20‡ 74, 75 E W law R Princeton ay — — 5:31 5:40 5:55 6:03‡ 6:08‡ a N POINT 5:59 6:05 6:14 6:25 6:34 6:42‡ 6:48‡ od venn 372 o ev 5:45 5:52 5:58 6:09 6:22 6:31‡ 6:36‡ Green Lk Kirkw RAVENNA 6:15 6:22 6:32 6:44 6:53 7:02‡ 7:08‡ ne W W HAWTHORNE A PARK GREEN t a — — 6:13 6:23 6:40 6:48‡ 6:53‡ 6:33 6:40 6:50 7:02 7:11 7:20‡ 7:26‡ ht53 So B HILLS LAKE N 55th St ood Pl l RAVENNA 6:15 6:22 6:28 6:39 6:55 7:05‡ 7:10‡ 6:48 6:55 7:05 7:17 7:26 7:35‡ 7:41‡ 62nd Ave NE N — — 6:40 6:51 7:09 7:18‡ -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

As a DiErent Route Through Downtown Buses Continuing INTERBAY Swedish S

N 152 St to Shoreline CC Snohomish County– to Aurora toAuroraVill toMtlk to Richmond NE 150 St toWoodinvilleviaBothell 373 5 SHORELINE 355 Village Beach Downtown Seattle toNSt Terr to Shoreline CC toUWBothell 308 512 402 405 410 412 347 348 77 330 309 toHorizonView 312 413 415 416 417 421 NE 145 St 373 308 NE 145 St toKenmoreP&R N 145 St 304 316 Transit in Seattle 422 425 435 510 511 65 308 toUWBothell 513 Roosevelt Wy N Frequencies shown are for daytime period. See Service Guide N 143 St 28 Snohomish County– 346 512 301 303 73 522 for a complete summary of frequencies and days of operation. 5 64 University District 5 E 304 308 For service between 1:30–4:30 am see Night Owl map. 512 810 821 855 860 E N 871 880 y 3 Av NW 3 Av Jackson Park CEDAR W Frequent Service N 135 St Golf Course OLYMPIC y Linden Av N Linden Av PARK t Bitter i Every 15 minutes or better, until 7 pm, Monday to Friday. C HILLS weekdays Lake e 372 Most lines oer frequent service later into the night and on NW 132 St Ingraham k a Ashworth Av N Av Ashworth N Meridian Av NE 1 Av NE 15 Av NE 30 Av L weekends. Service is less frequent during other times. (express) 373 77 N 130 St Roosevelt Wy NE 372 weekends 28 345 41 Link Light Rail rapid transit North- every 10 minutes BITTER LAKE acres 8 Av NW 8 Av Park 5 NW 125 St N 125 St Haller NE 125 St E RapidRide limited stop bus for a faster ride 345 Lake NE 125 St every 10–12 minutes 346 PINEHURST 8 Frequent Bus every 10–12 minutes BROADVIEW 99 347 348 continues as LAKE CITY 75 Frequent Bus every 15 minutes 41 345 NE 120 St Northwest -

Central Seattle

CENTRAL SEATTLE Capitol Hill Eastlake Leschi Madison Park Madrona Old Seattle charm, thriving urban center. Early in Seattle’s history, Capitol Hill and adjacent First Hill were where bankers, shipping executives and other newly rich called home. Today the neighborhood is a thriving urban center, and Broadway — the neighborhood’s main drag — serves as its focal point. Music and art are prominent cornerstones of this counter-culture community, with clubs, theatres, bookstores and galleries found all throughout the neighborhood. Internationally renowned Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) schedules showings at the Harvard Exit and Egyptian Theatres on Capitol Hill. During the academic year, Capitol Hill is filled with backpacking students who go to one of the nearby major institutions of higher learning — Seattle Central Community College and the nationally acclaimed Cornish College of the Arts. CAPITOL HILL Seattle University is on First Hill, but many of its students, faculty and staff neighborhood work and play on Capitol Hill. MADISON PARK neighborhood Madison Park, located south of the 520 bridge, is a neighborhood of stunning homes and condos, many with gorgeous views of the lake and Mount Rainer. Madison Park could be considered an urban center retreat, as it’s close to downtown Seattle and yet maintains the feeling of a lovely, slow-paced residential area. The upscale commercial district is both a draw to the neighborhood and greatly treasured by those who live nearby. CAPITOL HILL activities & community Farmer’s Market: The Capitol Hill Broadway Farmer’s Market is one of the few year-round markets in Seattle. The market is a wonderful opportunity to shop for fresh ingredients, learn about local non-profits, hear fun live music, and watch cooking demonstrations. -

4450 Green Lake Way N

4450 GREEN LAKE WAY N KIDDER.COM OFFERING MEMORANDUM | SEATTLE, WA CONTACT JASON ROSAUER 206.296.9608 [email protected] ROB ANDERSON, JD 206.296.9644 [email protected] KRISTYN KRUEGER 206.398.2270 TABLE OF [email protected] CONTENTS 01 INVESTMENT SUMMARY KIDDER.COM The Offering Offering Process The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only Investment Highlights by the party receiving it from Kidder Mathews and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Kidder Mathews. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only 02 a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence PROPERTY OVERVIEW investigation. Kidder Mathews has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income Existing Structure or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the Site Overview property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal Property Details regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the Property Financials financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Kidder Mathews has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Kidder Mathews conducted any investigation regarding these 03 matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. -

Foldrite Template Master

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL Dancing Family Fun Center City Cinema Music And Concerts - MUSIC UNDER THE STARS DANCING ‘TIL DUSK BACK TO SCHOOL BBQ WITH SOUNDERS FC Join us for movies under the stars! Pre-movie DOWNTOWN SUMMER SOUNDS Freeway Park activities start at 6 p.m. and the movie begins Freeway Park ♦ Hing Hay Park Denny Park City Hall, Denny, Freeway, Occidental Live broadcast of the performance from at dusk. Occidental Park ♦ Westlake Park BBQ, games and a backpack and school Square, and Westlake parks Benaroya Hall on 98.1 Classical KING FM. Thirteen magical evenings of free, live music and supplies giveaway. Fri., July 12 Cascade Playground Free live music at a variety of locations Bring a picnic! BBQs are available for grilling. social dancing (no experience or partner required). Saturday, Aug. 31 ♦ 11 a.m.-2 p.m. Spider-Man: Into the throughout downtown Seattle. Fridays, July 5, 12, 19, 26 ♦ 7-10 p.m. Spider Verse All programs run 6-9:30 p.m. BLOCK PARTY All programs run 12-1 p.m. SUMMER STAGE ♦ 6 p.m. - one-hour beginner lesson Cascade Playground Westlake Park Tue., July 9 City Hall Park Cascade Playground Aquaman ♦ 7 p.m. - Let the dancing begin! Free raffle, BBQ, bouncy houses and music. Fri., July 12 Denny Park Concerts in the park with talented local Visit www.danceforjoy.biz for more information Tuesday, Aug. 6 ♦ 4-8 p.m. Fri., July 19 Cascade Playground Tue., July 16 City Hall Park musicians! Up Fri., July 19 Denny Park Thu., July 11 Zydeco Hing Hay Park CASCADE KIDS DAYS Thursdays, June 13-Aug. -

Comprehensive List of Seattle Parks Bonus Feature for Discovering Seattle Parks: a Local’S Guide by Linnea Westerlind

COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF SEATTLE PARKS BONUS FEATURE FOR DISCOVERING SEATTLE PARKS: A LOCAL’S GUIDE BY LINNEA WESTERLIND Over the course of writing Discovering Seattle Parks, I visited every park in Seattle. While my guidebook describes the best 100 or so parks in the city (in bold below), this bonus feature lists all the parks in the city that are publicly owned, accessible, and worth a visit. Each park listing includes its address and top features. I skipped parks that are inaccessible (some of the city’s greenspaces have no paths or access points) and ones that are simply not worth a visit (just a square of grass in a median). This compilation also includes the best of the 149 waterfront street ends managed by the Seattle Department of Transportation that have been developed into mini parks. I did not include the more than 80 community P-Patches that are managed by the Department of Neighbor- hoods, although many are worth a visit to check out interesting garden art and peek at (but don’t touch) the garden beds bursting with veggies, herbs, and flowers. For more details, links to maps, and photos of all these parks, visit www.yearofseattleparks.com. Have fun exploring! DOWNTOWN SEATTLE & THE Kobe Terrace. 650 S. Main St. Paths, Seattle Center. 305 Harrison St. INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT city views, benches. Lawns, water feature, cultural institutions. Bell Street Park. Bell St. and 1st Ave. Lake Union Park. 860 Terry Ave. N. to Bell St. and 5th Ave. Pedestrian Waterfront, spray park, water views, Tilikum Place. 2701 5th Ave.