For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. 青島港國際股份有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. 青 島 港 國 際 股 份 有 限 公 司 (A joint stock company established in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 06198) VOLUNTARY ANNOUNCEMENT UPDATE ON THE PHASE III OF OIL PIPELINE PROJECT This is a voluntary announcement made by Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. (the “Company”, together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”). Reference is made to the voluntary announcement of the Company dated 28 December 2018, in relation to the groundbreaking ceremony for the phase III of the Dongjiakou Port-Weifang-Central and Northern Shandong oil pipeline construction project (the “Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project”). The Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project was put into trial operation on 8 January 2020. As of the date of this announcement, the Dongjiakou Port-Weifang-Central and Northern Shandong oil pipeline has extended to Dongying City in the north, opening the “Golden Channel” of crude oil industry chain from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Bay. SUMMARY OF THE PHASE III OF OIL PIPELINE PROJECT The Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project is the key project for the transformation of old and new energy in Shandong Province, and the key construction project of the Group. -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB6680 GEF Huai River Basin Marine Pollution Reduction Project Project Name Public Disclosure Authorized Region EAST ASIA AND PACIFIC Sector Sector: General water, sanitation and flood protection sector (55%); Pollution Control and Waste Management (45%) Project ID P108592 GEF Focal Area International waters Borrower(s) THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Implementing Agency Dongying Municipal Government, Shandong Province, China Office of Foreign Economy No. 127 Lishan Road, Lixia District Jinan Shandong 250013 Public Disclosure Authorized Tel: (86-531) 8697-4445 Fax: (86-531) 8694-2489 [email protected] Environment Category [ ] A [X] B [ ] C [ ] FI [ ] TBD (to be determined) Date PID Prepared June 23, 2011 Date of Appraisal July 8, 2011 Authorization Date of Board Approval October 31, 2011 1. Key development issues and rationale for Bank involvement 1.1 Over the past 30 years, China has seen impressive and unprecedented economic growth. Public Disclosure Authorized However, this rapid growth, compounded by population growth and urban migration, has been achieved at the cost of considerable deterioration of the water environment caused mostly by land-based pollution from industries, farming and domestic sources. This has alerted Chinese policy makers and general public to give pollution reduction and control a much higher priority and this is clearly articulated in the 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015), which aims to sustain the rapid and steady development of China’s “socialist market economy” following a green growth path. 1.2 The Huai River Basin covers four provinces, i.e. Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui and Henan. The key development challenge in the Huai River Basin is to maintain the balance between socio-economic development and environmental protection. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

8 June 2012 Norton Rose Australia ABN 32 720 868 049 Level 15, RACV Tower 485 Bourke Street MELBOURNE VIC 3000 AUSTRALIA Tel +61 3 8686 6000 Company Announcements Fax +61 3 8686 6505 Australian Securities Exchange GPO Box 4592, Melbourne VIC 3001 Level 2 DX 445 Melbourne 120 King Street nortonrose.com MELBOURNE VIC 3000 Direct line +61 3 8686 6710 Our reference Email 2781952 [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam Form 604 - Notice of change of interests of substantial shareholder We act for Linyi Mining Group Co., Ltd. (Linyi), a wholly owned subsidiary of Shandong Energy Group Co., Ltd. (Shandong Energy) in relation to its off-market takeover bid for all of the shares in Rocklands Richfield Limited ABN 82 057 121 749 (RCI). On behalf of Linyi, Shandong Energy and their related bodies corporate, we enclose a Notice of change of interests of substantial holder (Form 604) in respect of RCI. This Form 604 is being provided in accordance with section 671B(1)(c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) because Linyi has made an off-market takeover bid for all the shares in RCI in respect of which it issued a bidder’s statement on 7 June 2012. A copy of the enclosed Form 604 is being provided to RCI today. Yours faithfully James Stewart Partner Norton Rose Australia Encl. For personal use only APAC-#14668568-v1 Norton Rose Australia is a law firm as defined in the Legal Profession Acts of the Australian states and territory in which it practises. Norton Rose Australia together with Norton Rose LLP, Norton Rose Canada LLP, Norton Rose South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) and their respective affiliates constitute Norton Rose Group, an international legal practice with offices worldwide, details of which, with certain regulatory information, are at nortonrose.com 604 page 2/2 15 July 2001 Form 604 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of change of interests of substantial holder To Company Name/Scheme Rocklands Richfield Limited (RCI) ACN/ARSN ACN 057 121 749 1. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 18

Factory Factory Address Country Sector FTE No. workers % Male % Female ESSENTIAL CLOTHING LTD Akulichala, Sakashhor, Maddha Para, Kaliakor, Gazipur, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 669 55% 45% NANTONG AIKE GARMENTS COMPANY LTD Group 14, Huanchi Village, Jiangan Town, Rugao City, Jaingsu Province, China CHINA Garments 159 22% 78% DEEKAY KNITWEARS LTD SF No. 229, Karaipudhur, Arulpuram, Palladam Road, Tirupur, 641605, Tamil Nadu, India INDIA Garments 129 57% 43% HD4U No. 8, Yijiang Road, Lianhang Economic Development Zone, Haining CHINA Home Textiles 98 45% 55% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% 17% ASIAN LEATHERS LIMITED Asian House, E. M. Bypass, Kasba, Kolkata, 700017, India INDIA Accessories 978 77% 23% AMAN KNITTINGS LIMITED Nazimnagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 1708 60% 30% V K FASHION LTD formerly STYLEWISE LTD Unit 5, 99 Bridge Road, Leicester, LE5 3LD, United Kingdom UK Garments 51 43% 57% AMAN GRAPHIC & DESIGN LTD. Najim Nagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 3260 40% 60% WENZHOU SUNRISE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. Floor 2, 1 Building Qiangqiang Group, Shanghui Industrial Zone, Louqiao Street, Ouhai, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China CHINA Accessories 716 58% 42% AMAZING EXPORTS CORPORATION - UNIT I Sf No. 105, Valayankadu, P. Vadugapal Ayam Post, Dharapuram Road, Palladam, 541664, India INDIA Garments 490 53% 47% ANDRA JEWELS LTD 7 Clive Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex, TN35 5LD, United Kingdom UK Accessories 68 CAVENDISH UPHOLSTERY LIMITED Mayfield Mill, Briercliffe Road, Chorley Lancashire PR6 0DA, United Kingdom UK Furniture 33 66% 34% FUZHOU BEST ART & CRAFTS CO., LTD No. 3 Building, Lifu Plastic, Nanshanyang Industrial Zone, Baisha Town, Minhou, Fuzhou, China CHINA Homewares 44 41% 59% HUAHONG HOLDING GROUP No. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

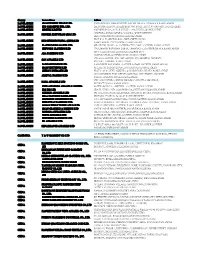

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Annual Report 2019

HAITONG SECURITIES CO., LTD. 海通證券股份有限公司 Annual Report 2019 2019 年度報告 2019 年度報告 Annual Report CONTENTS Section I DEFINITIONS AND MATERIAL RISK WARNINGS 4 Section II COMPANY PROFILE AND KEY FINANCIAL INDICATORS 8 Section III SUMMARY OF THE COMPANY’S BUSINESS 25 Section IV REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 33 Section V SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 85 Section VI CHANGES IN ORDINARY SHARES AND PARTICULARS ABOUT SHAREHOLDERS 123 Section VII PREFERENCE SHARES 134 Section VIII DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS, SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND EMPLOYEES 135 Section IX CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 191 Section X CORPORATE BONDS 233 Section XI FINANCIAL REPORT 242 Section XII DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE FOR INSPECTION 243 Section XIII INFORMATION DISCLOSURES OF SECURITIES COMPANY 244 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Board, the Supervisory Committee, Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of contents of this annual report (the “Report”) and that there is no false representation, misleading statement contained herein or material omission from this Report, for which they will assume joint and several liabilities. This Report was considered and approved at the seventh meeting of the seventh session of the Board. All the Directors of the Company attended the Board meeting. None of the Directors or Supervisors has made any objection to this Report. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Certified Public Accountants LLP (Special General Partnership)) have audited the annual financial reports of the Company prepared in accordance with PRC GAAP and IFRS respectively, and issued a standard and unqualified audit report of the Company. All financial data in this Report are denominated in RMB unless otherwise indicated. -

20200316 Factory List.Xlsx

Country Factory Name Address BANGLADESH AMAN WINTER WEARS LTD. SINGAIR ROAD, HEMAYETPUR, SAVAR, DHAKA.,0,DHAKA,0,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS GARMENTS IND. LTD. 255, NASIRABAD I/A, BAIZID BOSTAMI ROAD,,,CHITTAGONG-4211,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH DENITEX LIMITED 9/1,KORNOPARA, SAVAR, DHAKA-1340,,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH JAMIRDIA, DUBALIAPARA, VALUKA, MYMENSHINGH BANGLADESH PIONEER KNITWEARS (BD) LTD 2240,,MYMENSHINGH,DHAKA,BANGLADESH PLOT # 49-52, SECTOR # 08 , CEPZ, CHITTAGONG, BANGLADESH HKD INTERNATIONAL (CEPZ) LTD BANGLADESH,,CHITTAGONG,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH FLAXEN DRESS MAKER LTD MEGHDUBI, WARD: 40, GAZIPUR CITY CORP,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH NETWORK CLOTHING LTD 228/3,SHAHID RAWSHAN SARAK, CHANDANA,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH 521/1 GACHA ROAD, BOROBARI,GAZIPUR CITY BANGLADESH ABA FASHIONS LTD CORPORATION,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE- AMTOIL, P.O. HAT AMTOIL, P.S. SREEPUR, DISTRICT- BANGLADESH SAN APPARELS LTD MAGURA,,JESSORE,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH TASNIAH FABRICS LTD KASHIMPUR NAYAPARA, GAZIPUR SADAR,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH CHERRY INTIMATE LTD PLOT # 105 01,DEPZ, ASHULIA, SAVAR,DHAKA,DHAKA,BANGLADESH COLOMESSHOR, POST OFFICE-NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD SADAR,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE-JOYPURA, UNION-SHOMBAG,,UPAZILA-DHAMRAI, BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD DISTRICT,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH VINTAGE DENIM APPARELS LIMITED BOHERARCHALA , SREEPUR,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS IDR LTD CDA PLOT NO: 15(P),16,MOHORA -

Albania Bangladesh MANUFACTURING SITES

MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2020 No of Manufacturing Site Name Product Type Address Employees Albania Italstyle Shpk Accessories Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat 100 - 500 Bangladesh A One (Bd) Ltd Apparel Plot No 114-120 Depz Ganakbari Ashulia Dhaka-1349 1000 - PLUS Abanti Colour Tex Ltd Accessories Plot S A 646 Shashongaon Enayetnagar Fatullah Narayanganj 1000 - PLUS Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Home Furnishing Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 1000 - PLUS Adury Apparels Ltd Apparel Karardi Shibpur Narshingdi 1000 - PLUS Ajax Sweater Ltd Apparel Zirabo Bazar Ashulia Epz Road Savar Dhaka 1341 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Apparel 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1000 - PLUS Akh Shirts Ltd & Akh Fashions Ltd Apparel 133 34 Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1000 - PLUS Akm Knit Wear Limited Apparel Karnapara Savar Dhaka 1000 - PLUS Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Apparel Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 1000 - PLUS Aman Knittings Limited Apparel 5th Floor Kulasur Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1000 - PLUS Amantex Limited Apparel Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur 1000 - PLUS Ananta Apparels Ltd - Adamjee Epz Apparel Plot 246 - 249 Adamjee Epz Narayanganj 1431 1000 - PLUS Ananta Garments Ltd Apparel Nistapur Ashulia Depz Road Savar Dhaka 1341 1000 - PLUS A-One Polar Ltd Apparel Vulta Rupgonj Narayangonj Dhaka 1000 - PLUS Aptech Caswier Ltd Apparel Aptech Industrial Park Holding 30 Sarabo Kashimpur Gazipur 500 - 1000 Arabi Fashions Ltd Apparel Bokran Monipur Mirzapur Gazipur 1000 - PLUS Armour Garments Ltd Apparel 380 13 1 East Rampura -

China, 11/09/2019 SUEZ NWS Wins Industrial Wastewater Treatment

China, 11/09/2019 SUEZ NWS Wins Industrial Wastewater Treatment Project in Dongying to Optimize Water Resources Following a project win to treat drinking water in Qingdao, Shandong, SUEZ NWS has recently won a contract with total investment of RMB 300 million for centralized wastewater treatment in the Dongying Chemical Industry Park located in Dongying, Shandong. The project will boost local efforts to better manage water resources and further improve the environment. The envisaged wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in the Dongying Chemical Industry Park will have a treatment capacity of 26,000 m3 per day. A joint venture1 formed between SUEZ NWS and its local partner will be responsible for the investment, construction and operation of the plant. The plant will provide industrial wastewater treatment services exclusively for enterprises in the park for the next 50 years. Construction work will begin in late 2019 and be completed by late 2020. Upon its completion, the plant will provide centralized treatment of existing industrial wastewater streams in the park. It will also have capacity to meet the growing treatment demand from future park projects. The WWTP will ensure the production of high-quality treated wastewater in compliance with standards, and the reuse of 40% of this water to supply the industries of the Park. This will greatly improve the water environment and drive the local circular economy. Wang Feng, Deputy Secretary of the Dongying District Party Committee and District Head, said: "We hope that SUEZ NWS will exert its rich experience in the construction, operation and management of wastewater treatment plants in this project to promote the centralized treatment of wastewater in the park and concentrate on emission to effectively improve the district’s environment. -

CHINA Shandong Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve

CHINA Shandong Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve Chen Kelin and Yuan Jun Wetlands International-China Programme Yan Chenggao Ministry of Forestry, PRC THE CONTEXT Ecological profile Shandong Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve (11833-11920E, 3735-3812N) is situated in the northeast of Dongying City, Shandong Province, the People's Republic of China, which faces the Bohai Sea in the North and borders Laizhou Bay in the East (see appended map). It has a warm-temperate continental monsoon climate, with dry and windy spring, hot and rainy summer, cool and clear autumn, cold, dry and snowless winter. This area has an average annual temperature of 11.9C, a frost-free period of about 210 days, an average annual precipitation of 592 mm, mean annual evaporation of 1962 mm and average annual relative humidity of 68%. The Yellow River plays a dominant role in forming and maintaining the regional hydrology. The river has its lowest discharge from late March to June. With increasing water consumption upstream, especially the rapid development of water diversion works for irrigation, the river flow drys out frequently. The main flood season is from July to October, when there is heavy rainfall in the middle and lower reaches. From October to mid December, the river flow is steady. Then it will be ice bound season from the end December to March, during which the water level often rises drastically owing to poor drainage from ice blocking down the river channel. According to the observation data of Lijin hydrological station in the Yellow River Mouth from 1950 to 1985, the mean discharge is 41.9 billion m3, with an range from the maximum of 79.31 billion m3 to the minimum of 9.15 billion m3. -

Similarities and Differences in PM2.5, PM10 and TSP Chemical Profiles of Fugitive Dust Sources in a Coastal Oilfield City in China

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 14: 2017–2028, 2014 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2013.06.0226 Similarities and Differences in PM2.5, PM10 and TSP Chemical Profiles of Fugitive Dust Sources in a Coastal Oilfield City in China Shaofei Kong1,2*, Yaqin Ji2, Bing Lu2, Xueyan Zhao2,3, Bin Han2,3, Zhipeng Bai2,3* 1 Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, Key Laboratory for Aerosol- Cloud-Precipitation of China Meteorological Administration, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 2 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Nankai University, Weijin Road 94#, Tianjin, China 3 Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, Beijing 100012, China ABSTRACT PM2.5, PM10 and TSP source profiles for road dust, soil dust and re-suspended dust were established by adopting a re- suspension chamber in the coastal oilfield city of Dongying. Thirty-nine elements, nine ions, organic and elemental carbon 2+ 2– were analyzed by multiple methods. The results indicate that Ca, Si, OC, Ca , Al, Fe and SO4 were the most abundant species for all the three types of dust within the three size fractions. OC/TC ratios were highest for dusts in Dongying when compared with those in the literature, which may be related to the large amounts of oil that is consumed in this area. Na, Mg and Na+ in soil and road dust also exhibited higher mass percentages, indicating the influence of sea salt, as the city is close to the coast. Enrichment factors analysis showed that Cd, Ca, Cu, Zn, Ba, Ni, Pb, Cr, Mg and As were enriched, and these elements were more abundant in finer fractions of the fugitive dust.