In and out of Years and Over a Century of Picturebooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 109 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #377 - Beatrix Potter Original Art done for Anne Carroll Moore #328 - Velveteen Rabbit - 1st in dw #305 - Rare Cold War moveable #127 - First Mickey Mouse book #253 - Lawson Ferdinand drawing sgd by Leaf #254 - Ferdinand 1st edition signed in dw Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] ABC MANUSCRIPT WITH BOOK, DRAWINGS AND DUMMY RARE TUCK RAG 1. ABC.ABC MANUSCRIPT. Offered here is a fantastic group of items comprising “BLACK” ABC the various phases of the development of a book from rough dummy to published work. -

4–9–02 Vol. 67 No. 68 Tuesday April 9, 2002 Pages 16969–17278

4–9–02 Tuesday Vol. 67 No. 68 April 9, 2002 Pages 16969–17278 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 22:30 Apr 08, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\09APWS.LOC pfrm04 PsN: 09APWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 68 / Tuesday, April 9, 2002 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202–523–5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–523–5243 issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Exploring Illustrations of Caldecott Award Books to Increase Vocabulary Acquisition

A Picture’s Worth a Thousand Words: Exploring Illustrations in Caldecott Award Books to Increase Vocabulary Acquisition Klair McGlynn Shawmont Elementary School Overview Rationale Objectives Strategies Classroom Activities Annotated Bibliography/Resources Appendix/Content Standards Overview "What is the use of a book," thought Alice "without pictures or conversation?" ~from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland The objective of the curriculum unit, A Picture’s Worth a Thousand Words: Exploring Illustrations in Caldecott Award books to Increase Vocabulary Acquisition, is to examine how the award winning illustrations capture the emotional appeal and responses of both young and old viewers and to provide a plethora of learning opportunities to build vocabulary in a kindergarten classroom. It will provide an introduction to Children‟s Literature through picture books and their illustrations with implications for educators to utilize illustrations to teach new words. After presenting a brief history and criteria for selection of this prestigious distinction, this unit will focus on the merits of using the Caldecott Award books to teach vocabulary development. Educators should recognize the elements of Caldecott books that appeal to children, which include their illustrations, characters, and genres. These books can be used to enhance student learning in a variety of ways. The books can be readily integrated with different subjects, related to important character principles, and used as a source of inspiration. Understanding the appeal and potential uses of Caldecott books can help teachers to value these books as vital resources for their classrooms. This unit is intended for kindergarten students in a self-contained classroom. It should be completed after the second marking period when students have developed basic concepts of print and can engage in and experiment in reading and writing. -

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

A Brief History of Children's Storybooks

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AN ORIGINAL STORY WITH RELIEF PRINT ILLUSTRATIONS MARILYN TURNER MCPHERON Fall 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Art with honors in Art Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robin Gibson Associate Professor of Art Thesis Supervisor Jerrold Maddox Professor of Art Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College ABSTRACT Children’s literature, in the form of picture and storybooks, introduce a child to one of the most important tools needed to succeed in life: the ability to read. With the availability of affordable books in the 18th century, due to the introduction of new mechanization, individuals had the ability to improve their lives and widen their worlds. In the 19th century, writers of fiction began to specialize in literature for children. In the 20th century, books for children, with beautiful, colorful illustrations, became a common gift for children. The relatively rapid progression from moralistic small pamphlets on cheap paper with crude woodcuts to the world of Berenstain Bears, colorful Golden Books, and the tongue-twisters of Dr. Seuss is an intriguing social change. The story of how a storybook moves from an idea to the bookstore shelf is equally fascinating. Combining the history of children’s literature with how a storybook is created inspired me to write and illustrate my own children’s book, ―OH NO, MORE SNOW!‖ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Schreyer Honors College, -

MPLC Producer List Is Broken Down Into Seven Genres for Your Programming Needs

9/1/2020 CLU CLU The MPLC producer list is broken down into seven genres for your programming needs. Subject to the Umbrella License ® Terms and Conditions, Licensee may publicly perform copyrighted motion pictures and other audiovisual programs intended for personal use only, from the list of producers and distributors below in the following category: General Membership Clubs MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios (f/k/a Twentieth Buena Vista Pictures Cannon Pictures Century Fox Film Corp.) Dreamworks Animation SKG Dreamworks Pictures (Releases 2011 to Dreamworks Pictures (Releases prior to present) 2011) Fine Line Features Focus Features Fox - Walden Fox 2000 Films Fox Look Hanna-Barbera Hollywood Pictures Lionsgate US Lorimar Telepictures Lucasfilm Marvel Studios Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios New Line Cinema Nickelodeon Movies Orion Pictures Paramount Classics Paramount Pictures Paramount Vantage Picturehouse Pixar Animation Studios Polygram Filmed Entertainment Republic Pictures RKO Pictures Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) STX Entertainment Touchstone Pictures United Artists Pictures Universal Pictures USA Films Walt Disney Pictures Warner Bros. Pictures Warner Independent Pictures CHILDRENS Central Park Media Cosgrove Hall Films DC Comics D'Ocon Dreamworks Classics (f/k/a Classic Family Entertainment Library Media) Golden Books Entertainment Harvey Entertainment Peter Pan Video Scholastic Entertainment Warner Bros. Animation Zodiak Kids Studios UK (fka The Foundation) 9/1/2020 -

The Magazine Celebrating Television's Golden Era of Scripted Programming

Issue #3 January 2016 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming 10 x 60’ DRAMA SERIES SEASON 2 IN PRODUCTION Photo: © Tibo & Anouchka – Capa Drama / Zodiak Fiction / Incendo / Canal + NATPE Stand: 533 Scripted OFC DecJan16.indd 2 04/01/2016 14:40 TBI_FC_VERSAILLES_Zodiak_AD.indd 1 21/12/2015 12:41 A Philosophy Teacher Finds Off-beat Ways to Impact and Change the Lives of his Adolescent Students Contact us at NATPE MIAMI 2016 Find us at Booth 225 www.tv3.cat/sales [email protected] pXX TV3 DecJan16.indd 1 15/12/2015 11:14 In this issue Editor’s Note In the international television business of January 2016, the concept of ‘packaging’, which underpins the American film and TV industries, is not normal procedure. Fast-talking agents and demanding talent representatives exist everywhere, of course, but only in the US do you have that kind of standardised process that links actors, directors and writers to scripts doing the rounds. Now, with US channels keener than ever to work with international partners on high-end drama series, the American agent is branching out from Los Angeles and New York City. Not only that, they see 4 the skill set their regular days jobs have provided – negotiation tactics, rights ownership knowledge, contracting and, crucially, the gift of the gab – as proof that they can sell these packages overseas. In our lead feature on new BBC-AMC spy thriller The Night Manager, William Morris Endeavor’s head of global television, Chris Rice, explains how the famous LA agency became player in international distribution. -

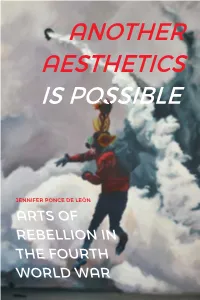

Another Aesthetics Is Possible

ANOTHER AESTHETICS IS POSSIBLE JENNIFER PONCE DE LEÓN ARTS OF REBELLION IN THE FOURTH WORLD WAR another aesthetics is pos si ble dissident acts A series edited by Macarena Gómez- Barris and Diana Taylor ANOTHER AESTHETICS IS POS SI BLE JENNIFER PONCE DE LEÓN ARTS OF REBELLION IN THE FOURTH WORLD WAR duke university press durham and london 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Aimee Harrison Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and Montserrat by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Ponce de León, Jennifer, [date] author. Title: Another aesthetics is possible : arts of rebellion in the Fourth World War / Jennifer Ponce de León. Other titles: Dissident acts. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: Dissident acts | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020027258 (print) LCCN 2020027259 (ebook) ISBN 9781478010203 (hardcover) ISBN 9781478011255 (paperback) ISBN 9781478012788 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Art and society—Argentina. | Art and society—Mexico. | Art and society—United States. | Social movements in art. | Art—Political aspects. | Aesthetics— Political aspects. | Aesthetics—Social aspects. Classification: LCC N72.S6 P663 2021 (print) | LCC N72.S6 (ebook) | DDC 701/.03—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020027258 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020027259 Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Cover art: Francisco Papas Fritas (Francisco Tapia Salinas), painting from the series Folk lor insurrecto, 2017. -

Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making PREMS 162317

INFORMATION DISORDER : Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making PREMS 162317 ENG Council of Europe report Claire Wardle, PhD Hossein Derakhshan DGI(2017)09 Information Disorder Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking By Claire Wardle, PhD and Hossein Derakhshan With research support from Anne Burns and Nic Dias September 27, 2017 The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the Directorate of Communications (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). Photos © Council of Europe Published by the Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex www.coe.int © Council of Europe, October, 2017 1 Table of content Author Biographies 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 10 Part 1: Conceptual Framework 20 The Three Types of Information Disorder 20 The Phases and Elements of Information Disorder 22 The Three Phases of Information Disorder 23 The Three Elements of Information Disorder 25 1) The Agents: Who are they and what motivates them? 29 2) The Messages: What format do they take? 38 3) Interpreters: How do they make sense of the messages? 41 Part 2: Challenges of filter bubbles and echo chambers 49 Part 3: Attempts at solutions 57 Part 4: Future trends 75 Part 5: Conclusions 77 Part 6: Recommendations 80 Appendix: European Fact-checking and Debunking Initiatives 86 References 90 2 Authors’ Biographies Claire Wardle, PhD Claire Wardle is the Executive Director of First Draft, which is dedicated to finding solutions to the challenges associated with trust and truth in the digital age. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

GOLDEN MEAN: COMMERCIAL CULTURE, MIDDLE-CLASS IDEALS, AND THE LITTLE GOLDEN BOOKS By JULIE SINN CASSIDY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Julie Sinn Cassidy 2 To all the Sinns and Scheitlins 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Before all else and for so many reasons, I thank my husband David J. Cassidy, a documentary film producer who will forever be plagued by a Partridge family pop star. This project on Little Golden Books came to fruition under the guidance of Dr. John Cech, to whom I am deeply grateful. Moreover, I want to thank my dissertation committee—Dr. Kenneth Kidd, Dr. Marsha Bryant, and Dr. Linda Lamme—for providing excellent insight, feedback, and encouragement throughout this process. They have all challenged and shaped me as a writer and scholar. For her editorial eye, I would also like to thank Miriam Downey, who read every word of this dissertation multiple times. This project would not have been possible without two specific Little Golden Book collectors, Steve Santi and Holly Everson, who provided me with access to their collections and answered my numerous questions. Diane Muldrow, the current editor of the Little Golden Books at Random House, graciously filed in any information gaps. The generous Children’s Literature Association’s Hannah Beiter Graduate Student Scholarship and the University of Florida’s O. Ruth McQuown Supplemental Scholarship for Graduate Women provided me with the funds to travel across the country, dig through archives, and present at conferences. -

Social Construction of Gender-(Un)Fairness an Analysis of Educational Material and Individual Language

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin Social Construction of Gender-(un)fairness An Analysis of Educational Material and Individual Language Use Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von lic. phil. Franziska Moser Berlin, 2013 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Bettina Hannover, Freie Universität Berlin Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Sabine Sczesny, Universität Bern Disputation: 5. Juli, 2013 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements For reasons of data protection, the acknowledgements are not included in this version. Table of contents Table of Contents Abstract Zusammenfassung Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Social construction of gender-(un)fairness – The educational level 8 Study 1: Subtile und direkte Mechanismen der sozialen Konstruktion von Geschlecht 29 Study 2: How gender-fair are German schoolbooks in the 21st century? 50 Study 3: Are there signs of change? 78 Chapter 3: Social construction of gender-(un)fairness – The individual level 96 Study 4: Who uses gender-inclusive language? 99 Chapter 4: General Discussion 127 References 147 Curriculum vitae 168 List of publications 170 Appendix 171 Erklärung This research was conducted within the Marie Curie Initial Training Network: Language, Cognition, & Gender, ITN LCG, funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n°237907 (www.itn-lcg.eu). Abstract Abstract The issues of gender roles, gender development and gender equality have been subject to research for several decades. Many studies have shown that traditional gender roles still prevail, if to a lesser extent than in past decades. Also indices of gender equality still point to gaps in the economic and political participation of female and male persons. -

Escuela Superior Politécnica Del Litoral Escuela De Postgrado En Administración De Empresas Maestría En Gestión De Proyectos

ESCUELA SUPERIOR POLITÉCNICA DEL LITORAL ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO EN ADMINISTRACIÓN DE EMPRESAS MAESTRÍA EN GESTIÓN DE PROYECTOS TESIS DE GRADO PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE: MAGISTER EN GESTIÓN DE PROYECTOS TEMA: APERTURA DE UN CENTRO DE ACTIVIDADES LITERARIAS PARA NIÑOS EN LA CIUDAD DE GUAYAQUIL AUTORES: Aline Gutiérrez Northía María Lorena Vera Lino Iván González Aguayo DIRECTOR: María Luisa Granda, PhD. Guayaquil - Ecuador Octubre 2013 I Sin duda alguna, dedico la tesis a Papaito Dios, ser divino que derrama en mi muchas bendiciones de superación, fortaleza y lucha constante a lo largo de mi vida. A mi madre, más que una bendición es mi ángel de la tierra, que gracias a su apoyo incondicional y su maravilloso amor he salido adelante atravesando obstáculos y alcanzando metas. A mi hermanita Crys que con su alegría y su gran cariño me ha fortalecido en todo momento. A mi abuelita y Tíos: Antonio, Lucia, Españita, Luis y Clemencia, mi gran familia que siempre me respalda en toda decisión. A mis amigos Ivan y Aline porque como equipo logramos cumplir nuestro objetivo de graduarnos, llevándonos cada uno de nosotros el tesoro de una valiosa amistad. Finalmente les dejo mi frase motivadora: “El amor de Dios y de tus seres queridos hacia a ti es la herramienta que jamás puede faltar para emprender tus sueños, ten claro tus objetivos, tu alcance y fechas propuesta porque solo depende de Ti, los logros que tengas en la vida…” Lorena II A la memoria de mi querido tío Angel Bolivar Cuadrado, siempre es una fuente de inspiración recordar su lucha.