Bertrand Goldberg Preserving a Vision of Concrete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lbbert Wayne Wamer a Thesis Presented to the Graduate

I AN ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE USE BUILDING; by lbbert Wayne Wamer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Lehigh University 1982 TABLE OF CCNI'ENTS ABSI'RACI' 1 1. INTRODlCI'ICN 2 2. THE CGJCEPr OF A MULTI-USE BUILDING 3 3. HI8rORY AND GRami OF MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS 6 4. WHY MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS ARE PRACTICAL 11 4.1 CGVNI'GJN REJUVINATICN 11 4. 2 EN'ERGY SAVIN CS 11 4.3 CRIME PREVENTIOO 12 4. 4 VERI'ICAL CANYOO EFFECT 12 4. 5 OVEOCRO'IDING 13 5. DESHN CHARACTERisriCS OF MULTI-USE BUILDINCS 15 5 .1 srRlCI'URAL SYSI'EMS 15 5. 2 AOCHITECI'URAL CHARACTERisriCS 18 5. 3 ELEVATOR CHARACTERisriCS 19 6. PSYCHOI..OCICAL ASPECTS 21 7. CASE srUDIES 24 7 .1 JOHN HANCOCK CENTER 24 7 • 2 WATER TOiVER PlACE 25 7. 3 CITICORP CENTER 27 8. SUMMARY 29 9. GLOSSARY 31 10. TABLES 33 11. FIGJRES 41 12. REFERENCES 59 VITA 63 iii ACKNCMLEI)(}IIENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. Lynn S. Beedle for the supervision of this project and review of this manuscript. Research for this thesis was carried out at the Fritz Engineering Laboratory Library, Mart Science and Engineering Library, and Lindennan Library. The thesis is needed to partially fulfill degree requirenents in Civil Engineering. Dr. Lynn S. Beedle is the Director of Fritz Laboratory and Dr. David VanHom is the Chainnan of the Department of Civil Engineering. The author wishes to thank Betty Sumners, I:olores Rice, and Estella Brueningsen, who are staff menbers in Fritz Lab, for their help in locating infonnation and references. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~ _ B-1382 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Completelhe National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property I historic name Highfield House____________________________________________ other names B-1382___________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4000 North Charles Street ____________________ LJ not for publication city or town Baltimore___________________________________________________ D vicinity state Maryland code MD county Baltimore City code 510 zip code 21218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E] meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide ^ locally. -

The Dearborn Express Sponsored by the South Loop Referral Group

The Dearborn Express Sponsored by the South Loop Referral Group Serving Printers Row and Dearborn Park Al Hippensteel, editor [email protected] Sept 30th, 2015 Vol. 3, No.13 River South Mega-Development Meets the In this Issue Plan Commission http://chicago.curbed.com/ The September meeting of Lorraine Schmall reviews the book, the Chicago Plan Com- mission was held yester- “The Girl Who was Saturday day and at the end of the Night, by Heather O’Neal. agenda was an unveiling of plans for the empty On Page 7. riverfront property south of River City to be devel- oped by a joint venture of Mike interrupts this Debate for the Chicago based CMK and “Truth.” Page 5 Sydney, Australia based Lend Lease. Developer CMK Companies had pur- chased nearly all of the vacant property along the South Branch of the Chi- Margaret Wallyn provides us cago River between Harri- Rendering via CMK] son Street and Roosevelt Road last with a restaurant review for winter in three different transactions and proposed a Asian Outpost. Page 9 mega-development for the site calledRiver South. Chi- cago based architecture firm Perkins+Will was then hired to lead the site planning for the project to be con- structed on both sides of the existing River City. Original plans for the mixed-use River City complex by architect Bertrand Goldberg were much grander INDEX than what ended up getting built, including a visionary Jazz Showcase ………...……… ……….……….……...….……...………....p 2 concept of three 72 story cylindrical towers. These tow- South Loop Neighbors………..…...…………….…………….…….…...…p 3 ers, referred to as the "River City Triad" were to be Bonnies Blog …………...….....…………….……….…...………….….……..p 4 similar in design to the famous towers at Marina City on the main branch of the river, except this version was Mondays with Mike.………….………………………………………………..p 5 11 stories taller and was to include three intermediate Book Review ………………….....….…………...………………………………p 7 skybridges linking the towers roughly every 18 floors. -

Chicago's First Lady Cruises 2018 Fact Sheet

Media Contact: Michael Queroz Lauren Martin Public Communications Inc. Public Communications Inc. [email protected] [email protected] (312)558-1770 (312)558-1770 Chicago’s First Lady Cruises 2018 Fact Sheet About Chicago’s First Lady Cruises • This year marks the 25th anniversary of Chicago’s First Lady Cruises and the Chicago Architecture Center (CAC)’s – formerly known as the Chicago Architecture Foundation (CAF) – partnership connecting Chicago locals and visitors to the city’s rich architectural history through the official Chicago Architecture Foundation Center River Cruise aboard Chicago’s First Lady. • The CAFC River Cruise aboard Chicago’s First Lady is the #1 ranked tour in Chicago based on TripAdvisor user reviews. • Guests often praise the cruise as the best way to see Chicago’s world-famous skyscrapers in their entirety and at angles that cannot be seen by foot. • The 90-minute boat cruise is the most in-depth architecture river tour available. They include interpretations by passionate CAC-certified volunteer docents of more than 50 buildings along the Chicago River, as well as insights into the city’s rich architectural history. • CAC-certified docents undergo nearly 100 hours of rigorous training through the CAC. • The Twilight River Cruise occurs at sunset and provides guests the traditional daytime cruise experience in a serene atmosphere. • The Capture Chicago Photography Cruise is a docent-led tour available for photographers throughout the summer that includes three pauses throughout the cruise for prime photography opportunities. • Tours include views of iconic buildings including: Tribune Tower, Wrigley Building, Marina City, Merchandise Mart, Civic Opera House, Aqua Tower and newer buildings such as 150 N. -

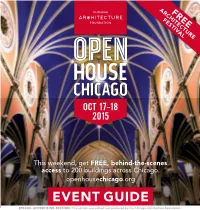

EVENT GUIDE SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION: This Section Was Edited and Produced by the Chicago Architecture Foundation

ARCHITECTUREFREE FESTIVAL This weekend, get FREE, behind-the-scenes access to 200 buildings across Chicago. openhousechicago.org EVENT GUIDE SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION: This section was edited and produced by the Chicago Architecture Foundation. 1 PRESENTED BY About the Chicago Architecture Foundation Five years ago, the Chicago to embark on a tour, workshops for Architecture Foundation (CAF) students, lectures for adults and decided to bring a city-wide festival of field trip groups gathered around architecture and design to Chicago— our 1,000-building scale model of the quintessential city of American Chicago. architecture. London originated the In addition to Open House Chicago, “Open House” concept more than 20 CAF is best known for our 85 different years ago, New York City had several Chicago-area tours, including the top- years under its belt and even Toronto ranked tour in the city: the Chicago produced a similar festival. By 2011, it Architecture Foundation River Cruise was Chicago’s time and Open House aboard Chicago’s First Lady Cruises. Chicago was born. Our 450 highly-trained volunteer CAF was founded in 1966. As a docents lead more than 6,000 walking, STS. VOLODYMYR & OLHA UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC CHURCH (P. 10) photo by Anne Evans nonprofit organization dedicated boat, bus and L train tours each year. to inspiring people to discover why CAF also offers exhibitions, public designed matters, CAF has grown programs and education activities Ten things to know about over the years to become a hub for for all ages. Open House Chicago learning about and participating in Learn more about CAF and our architecture and design. -

Hotel Recommendations

Hotel Recommendations The CTBUH recommends staying at one of the many downtown hotel options and taking a taxi or CTA Green Line train to and from the IIT campus. Most downtown hotels are about 10-15 minutes by taxi or Green Line train. 5-star Hotels 4-star Hotels Four Seasons Hotel Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 120 E. Delaware Pl, Chicago, IL 60611 230 N. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60601 www.fourseasons.com/chicagofs/ www.hardrockhotelchicago.com/ Located across from the John Hancock Building at the north end of the Magnicent Mile, this Located on Michigan Avenue in the 1929 Carbide & Carbon Building with Art Deco hotel features unrivalled guest-room views of Lake Michigan and the city skyline. furnishings, just steps from the Loop and Millennium Park. Park Hyatt Chicago Hotel Burnham 800 N Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60611 1 West Washington, Chicago, IL 60602 http://parkchicago.hyatt.com/ www.burnhamhotel.com/ Located at Water Tower Square, across from the John Hancock building, and includes an Located in the Reliance Building, a National Historic Landmark built in 1895 by Burnham and award winning restaurant and a private art gallery. Root as one of the rst skyscrapers, this boutique hotel is located in the heart of the loop. Trump International Hotel & Tower Hotel Sax Chicago 401 N. Wabash Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611 333 N. Dearborn St, Chicago, IL 60654 www.trumpchicagohotel.com/ www.hotelsaxchicago.com/ The 2nd tallest building in the US, the Trump showcases panoramic views of the Chicago Located within the classic Marina City Towers in the heart of downtown, this chic boutique skyline and Lake Michigan. -

Les Numéros En Bleu Renvoient Aux Cartes

276 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. 10 South LaSalle 98 American Writers Museum 68 35 East Wacker 88 Antiquités 170, 211 55 West Monroe Building 96 Aon Center 106 57th Street Beach 226 Apollo Theater 216 63rd Street Beach 226 Apple Michigan Avenue 134 75 East Wacker Drive 88 Aqua Tower 108 77 West Wacker Drive 88 Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary 161 79 East Cedar Street 189 Architecture 44 120 North LaSalle 98 Archway Amoco Gas Station 197 150 North Riverside 87 Argent 264 181 West Madison Street 98 Arrivée 256 190 South LaSalle 98 Arthur Heurtley House 236 225 West Wacker Drive 87 Articles de voyage 145 300 North LaSalle Drive 156 Art Institute of Chicago 112 311 South Wacker Drive Building 83 Artisanat 78 321 North Clark 156 Art on theMART 159 A 325 North Wells 159 Art public 49 330 North Wabash 155 Arts and Science of the Ancient World: 333 North Michigan Avenue 68 Flight of Daedalus and Icarus 98 333 West Wacker Drive 87 Arts de la scène 40 360 CHICAGO 138 Astor Court 190 INDEX 360 North Michigan Avenue 68 Astor Street 189 400 Lake Shore Drive 158 AT&T Plaza 118 515 North State Building 160 Atwood Sphere 127 543-545 North Michigan Avenue 134 Auditorium Building 73 606, The 233 Auditorium Theatre 80 646 North Michigan Avenue 134 Autocar 258 730 North Michigan Avenue Building 137 Avion 256 860-880 North Lake Shore Drive 178 Axis Apartments & Lofts 179 875 North Michigan Avenue 138 900 North Michigan Shops 139 919 North Michigan Avenue 139 B 1211 North LaSalle Street 192 Baha’i House of Worship 247 1260 North Astor -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

INTERVIEW with JOSEPH FUJIKAWA Interviewed by Betty J. Blum

INTERVIEW WITH JOSEPH FUJIKAWA Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 1995 Revised Edition © 2003 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Outline of Topics vii Oral History 1 Selected References 31 Curriculum Vitæ 33 Index of Names and Buildings 35 iii PREFACE Since its inception in 1981, the Department of Architecture at The Art Institute of Chicago has engaged in presenting to the public and the profession diverse aspects of the history and process of architecture, with a special concentration on Chicago. The department has produced bold, innovative exhibitions, generated important scholarly publications, and sponsored public programming of major importance, while concurrently increasing its collection of holdings of architectural drawings and documentation. From the beginning, its purpose has been to raise the level of awareness, understanding, and appreciation of the built environment to an ever-widening audience. In the same spirit of breaking new ground, an idea emerged from the department’s advisory committee in 1983 to conduct an oral history project on Chicago architects. Until that time, oral testimony had not been used frequently as a method of documentation in the field of architecture. -

Marina City.” Chicago Tribune, November 12, 1994, P

DRAFT PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITTED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN JULY 2015 MARINA CITY 300-340 N. STATE ST.; 301-351 N. DEARBORN ST. CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner 1 2 CONTENTS Map of District 5 Development of Marina City 6 Residential Development in Post-War Chicago 6 William Lane McFetridge and the Building Service Employees International Union 8 Bertrand Goldberg, Early Life and Work (1913-1959) 12 Planning Marina City 14 The Site 15 Marina City and the “Total Environment” 15 The Design Phase 17 Building Marina City 19 Financing Marina City 22 Marketing and Public Reception of Marina City 25 Marketing and Publicity 25 Public Reception 27 Replicating the Model and the Legacy of Marina City 30 The Architecture of Marina City 31 Physical Description 31 Marina City and Expressionist Modern Architecture 35 Bertrand Goldberg After Marina City 39 Criteria for Designation 39 Significant Historical and Architectural Features 47 Selected Bibliography 48 Illustration Credits 52 Acknowledgments 53 3 MARINA CITY 300 N. STATE STREET PERIOD OF SIGNIFICANCE: 1960-1967 ARCHITECT AND ENGINEERS: BERTRAND GOLDBERG ASSOCIATES SEVERUD-ELSTAD-KRUEGER Marina City, designed by architect Bertrand Goldberg and constructed between 1960 and 1967, is an icon of Chicago architecture and urban planning. This “city within a city,” the first of its kind to layer residential, commercial, and entertainment uses into a dense high rise complex in the center city, was the most ambitious and forward-thinking post-war urban renewal project in Chicago in an era defined by ambitious urban renewal projects. -

Inside This Issue

VOICE The Journal of Preservation Chicago WINTER 20 11 ISSUE No 10 INSIDE THIS ISSUE LATHROP HOMES REDEVELOPMENT STIRS CONTROVERSEY Page 3 READ THE LATEST PRESERVATION STATUS REPORT Page 6 8 SCHLITZ TAVERNS LANDMARKED Page 7 333 East Superior St., 1975, Bertrand Goldberg - Bertrand Goldberg and Associates Architect Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum CAN GOLDBERG’S MODERN MASTERPIECE BE SAVED? Perhaps the most overused word in the architectural principles, resulting in a uniquely original design lexicon is “unique”. It has been bandied about so philosophy. Rather than steel and glass, he adopted frequently that when a truly revolutionary piece of concrete as his medium; its plasticity the ideal architecture is built, the word loses all its meaning. material to realize his vision. Goldberg opined that However, in 1975, when Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice there were no right angles in nature and strove to Women’s Pavilion opened on Chicago’s Northwestern create a more organic architecture, thus gravitating Hospital campus, the world witnessed the completion to more circular forms. of a structure that truly was unique. Now, merely 35 years old, this amazing masterwork is threatened Best known for his prescient Marina City, Goldberg with demolition. created a complete urban environment within a single development, a city within a city for urban Goldberg trained at Harvard and studied, for a time, professionals which provided affordable rental at the German Bauhaus under the direction of archi- housing, retail services, entertainment, and office -

A New Era of American Architectural Concrete: from Wright to Som First Volume

Roberto Gargiani A NEW ERA OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURAL CONCRETE: FROM WRIGHT TO SOM FIRST VOLUME TREATISE ON CONCRETE Treatise on Concrete Directed by Roberto Gargiani A NEW ERA OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURAL CONCRETE: FROM WRIGHT TO SOM FIRST VOLUME prologue chapter five. Effects of Scale and Prestressing: Surface Finishes by the Book: The Accomplishments Works by SOM and Mies of Architectural Concrete Goldsmith: Superstructure and Bracing Learning from Nervi chapter one. The Self-Built Construction of Wright SOM’s Quest for an Expressive Structure and Residential Fabrication Systems The Bridges and Prestressed Girders of SOM and Khan Wright’s Desert Concrete: Toward a Constructional New Paths of Gravity: Goldsmith and Lin Primitivism Mies’s Reinforced Trilith Textile and Concrete Blocks for the Usonian Houses The Experimental Residential Construction chapter six. The Skyscrapers of Mies, Kahn, and Wright of Rudolph and Goldberg The Unclear Structure of Mies and Severud The Monolithic Houses of Le Tourneau and IBEC for the Seagram Building The Lift Slab Method by Youtz & Slick and by the Johnson and the Enigma of Diagonal Bracing Vagtborg Corporation Kahn’s Tower of Triangular Concrete Frames The Richards Laboratories: Prefabrication chapter two. The Primitive Frame of Mies and Post-Tensioning Beauty is the Splendor of Truth: Mies’s Chicago Debut Wright’s Tripod Frame Construction and Molded Belluschi’s Equitable Building: The Copy Ornament The Promontory Apartments: The Degree Zero The Illinois Mile-High Cantilever Sky-City of the New Chicago Frame Prototype Variations chapter seven. Architectural Concrete Variations, Affordable Housing in Chicago, or the Miesian Aesthetic from Breuer to Saarinen Mo-Sai Precast Concrete Cladding Panels chapter three.