INTERVIEW with JOSEPH FUJIKAWA Interviewed by Betty J. Blum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

Download This

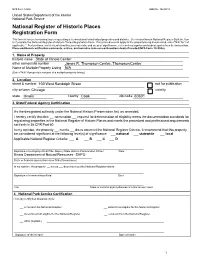

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~ _ B-1382 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Completelhe National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property I historic name Highfield House____________________________________________ other names B-1382___________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4000 North Charles Street ____________________ LJ not for publication city or town Baltimore___________________________________________________ D vicinity state Maryland code MD county Baltimore City code 510 zip code 21218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E] meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide ^ locally. -

Kimmel in the C M Nity

THE SIDNEY KIMMEL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER CENTE R AT JOHNS HOPKINS KIMMEL IN THE C MNITY PILLARS OF PROGRESS Closing the Gap in Cancer Disparities MUCH PROGRESS HAS been made in Maryland toward eliminating cancer disparities, and I am very proud of the role the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center has played in this progress. Overcoming cultural and institutional barriers and increasing minority participation in clinical trials is a priority at the Kimmel Cancer Center. Programs like our Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities, Office of Community Cancer Research, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund at Johns Hopkins, and Day at the Market are helping us obtain this goal. Historical Trends (1975-2012) The challenge before Maryland is greater than Mortality, Maryland most states. Thirty percent of Maryland’s citizens are All Cancer Sites, Both Sexes, All Ages Deaths per 100,000 resident population African-American, compared to a national average 350 of 13 percent. We view our state’s demographics as 300 black (includes hispanics) an opportunity to advance the understanding of 250 factors that cause disparities, unravel the science White (includes hispanics) 200 that may also play a contributory role, and become the model for the rest of the country. Our experts are 150 setting the standards for removing barriers and 100 hispanic (any race) improving cancer care for African-Americans and 50 other minorities in Maryland and around the world. 0 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Although disparities still exist in Maryland, we year of Death continue to close that gap. Overall cancer death rates have declined in our state, and we have narrowed the gap in cancer death disparities between African -American and white Marylanders by more than 60 percent since 2001, far exceeding national progress. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

50 Year Old Air Conditioning Systems in USA (How They Are Kept Operating and Energy Efficient)

CIBSE ASHRAE Group 15 February 2012 50 year old air conditioning systems in USA (How they are kept operating and energy efficient) David Arnold Partner, Troup Bywaters + Anders (D.Arnold@TBandA@com) Royal Academy Visiting Professor Faculty of Engineering, Science and Built Environment London South Bank University ([email protected]) Chicago Architecture and Art Showcase Chicago Architecture and Art Showcase Chicago Architecture and Art Showcase Trump International Hotel and Tower Fisher Building 50 year old air conditioning systems in USA John Hancock Richard J Daley Inland Steel Building Comparison Building Inland Steel Richard J Daley John Hancock Completed 1958 1965 1970 Floors / Height 19 / 101m (332ft) 31 / 203m (667'-5") 100 / 334m (1,127ft) Gross Floor Area 28,780m² 136,220m² 232,542m² Tinted Single/Double? Single Ground to 41 Thermal Tinted Single Full height glass Double 43 to 97 Dual Duct Perimeter Induction Perimeter Induction Air conditioning High Velocity (Changeover) (Changeover) Floor outlet CAV Reheat Interior CAV Reheat Interior Fuel Gas Heavy Oil / Gas Electric Boiler Power 10.3 MW 29MW 19.3MW Frig Power 3.3MW 29MW 24MW The Inland Steel Building - 1958 The Inland Steel Building - 1958 Interior Photo c1960 The Inland Steel Building - 1958 Steam Boiler (1957) Fans and Pneumatic Controls (1957) The Richard J Daley Center 1966 John Hancock Center 1970 Energy Saving Measures Energy Measure Inland Steel Richard J Daley John Hancock Digital Controls ✓✓✓ Inverter Drives ✓✓✓ CAV t o VAV ✓✓✓ Thermal Performance Retrofit Glazing -

S13 Chicago Trip Itinerary

st Architecture Studio: 1 Year Spring Coordinator: Kai Gutschow Spring 2013, CMU, Arch #48-105, M/W/F 1:30-4:20 Email: [email protected] Class Website: www.andrew.cmu.edu/course/48-105 Off. Hr: M/W/F 12:30-1:00pm & by appt. in MM302 (3/18/13) CHICAGO FIELD TRIP Thu. 11:30pm - Depart CMU MMCH, by bus: Kai cell phone: 412-606-6840 Fri. ca.8:00am - arrive Chicago (note time change, one hour earlier) Leave bags at H.I. Chicago: 24 East Congress Parkway, Chicago, 312‐360‐0300 Fri. approx. 9:00am - begin walking tour at HI Chicago hostel 1. Auditorium Bldg (Roosevelt U.), Sullivan [1887-90], 430 S. Michigan 2. Santa Fe Building, Burnham [1904], 224 S. Michigan (Chicago Arch’l Foundation) Visit Skidmore Owings & Merrill offices (10:00AM apptmt.) * Drawing assignment in lobbies 3. Monadnock Bldg, Burnham [1889-91], 53 W. Jackson Blvd. 4. Federal Center, Mies v.d. Rohe [1959-74] 219-230 Dearborn St. (Calder) 5. Rookery Building, Burnham [1885] F.L. Wright [1907], 209 S. La Salle St 6. Marquette Bldg, Holabird/Roche [1893-5] 140 S. Dearborn 7. Inland Steel Building, S.O.M. [1956-57], 30 W. Monroe St. 8. Carson Pirie Scott (Target?), Sullivan [1899], 1 S. State 9. Reliance Bldg (Hotel Burnham), Burnham [1891-95], 32 N. State St. 10. Marshall Fields (Macy’s), Burnham [1892-1907] 111 N. State LUNCH at Marshal Fields food courts (basement and top flor) 11. Civic Ctr (Daley Ctr), Murphy & SOM [1965], Washington/Dearborn (Picasso) 12. Thompson Ctr., Murphy/Jahn [1979-85], 100 W. -

Permit Review Committee Report

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS December 3, 2009 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held a regular meeting on December 3, 2009. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 N. LaSalle St., Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:55 p.m. PRESENT: David Mosena, Chairman John Baird, Secretary Yvette Le Grand Christopher Reed Patricia A. Scudiero, Commissioner Department of Zoning and Planning Ben Weese ABSENT: Phyllis Ellin Chris Raguso Edward Torrez Ernest Wong ALSO PRESENT: Brian Goeken, Deputy Commissioner, Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division Patricia Moser, Senior Counsel, Department of Law Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A tape recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division offices, and is part of the permanent public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Mosena called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of the November 5, 2009, Regular Meeting Motioned by Baird, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 2. Preliminary Landmark Recommendation UNION PARK HOTEL WARD 27 1519 W. Warren Boulevard Resolution to recommend preliminary landmark designation for the UNION PARK HOTEL and to initiate the consideration process for possible designation of the building as a Chicago Landmark. The support of Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward), within whose ward the building is located, was noted for the record. Motioned by Reed, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 3. Report from a Public Hearing and Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council CHICAGO BLACK RENAISSANCE LITERARY MOVEMENT Lorraine Hansberry House WARD 20 6140 S. -

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E. -

S Ep 25 196 2

S EP 25 196 2 .BRAR( REINFORCED CONCRETE STRUCTURAL FACADE, ITS APPLICATION FOR HIGH RISE OFFICE BUILDINGS by Robert P. Sitzenstock B. Arch., The Ohio State University 1954 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology July 1962 Signature of Author: Robert P. Sitzenstock Signature of Head of Department Lawrence B. Anderson V/ July 16, 1962 Pietro Belluschi, Dean School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 39, Massachusetts Dear Dean Belluschi:- In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Architecture, I hereby submit this thesis entitled "Reinforced Concrete Structural Facade, Its Application for High Rise Office Buildings." ResapcgXultj, Robert P. Sitzenstock A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S I am grateful to the following people for their invaluable advice and assistance during the thesis. Professor Giulio Pizzatti Turiu, Italy Doctor Howard Simpson Cambridge, Mass. Mr. A.J. Harris London, England Professor Eduardo F. Catalano ----- Advisor The members of the M.I.T. Faculty who participated in the preliminary thesis jury, May, 1962. C 0 N T E N T S Abstract 2 Exposition 3 High Rise Office Building Analysis 4 Design Criteria 17 Building Concept 20 Structural Concept 21 Calculations 24 Mechanical and Electrical Systems 39 Research Material 41 Drawings 1 A B S T R A C T This thesis is concerned with an investigation of reinforced concrete structural facade, its application for high rise office buildings. Special attention is given to the struc- tural mullion and its relationship to the floor and mechanical systems. -

Minutes of the Meeting Commission on Chicago Landmarks October 4, 2012

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS OCTOBER 4, 2012 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held a regular meeting on October 4, 2012. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 N. LaSalle St., City Hall Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:50 p.m. PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Rafael Leon, Chairman John Baird, Secretary Tony Hu James Houlihan (arrived after item 1) Ernest Wong Anita Blanchard Christopher Reed Mary Ann Smith Andrew Mooney, Commissioner of the Department of Housing and Economic Development ALSO PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Eleanor Gorski, Assistant Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development, Historic Preservation Division Arthur Dolinsky, Department of Law, Real Estate Division Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A tape recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Housing and Economic Development, Historic Preservation Division offices and is part of the permanent public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Leon called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of the September 6, 2012, Regular Meeting Motioned by Smith, seconded by Wong. Approved unanimously. (8-0) Commission member Jim Houlihan arrived. 2. Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council MARTIN SCHNITZIUS COTTAGE WARD 43 1925 N. Fremont Street Resolution to adopt the Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council that the MARTIN SCHNITZIUS COTTAGE be designated as a Chicago Landmark. Alderman Michelle Smith, (43rd Ward), within whose ward the building is located, expressed support for the designation. Michael Spock on behalf of the Barbara Spock Trust, the property owner, also expressed support for the landmark designation. -

9780714839622-Mies-Preview.Pdf

6 Introduction Critical Realism: Life and Form 14 Apprenticeship in Reform 20 Riehl House: Country House Critical Realism 32 Bismarck Memorial: Form and Space 44 Kröller-Müller Villa: Living Geometry Avant-garde: Art and Life 58 Glass Skyscraper: New Beginnings 82 Good Forms for New Types 92 Esters and Lange Houses: New Language 114 Weissenhofsiedlung: Urban Montage Task: Mastering Modernity 138 Barcelona Pavilion: Spiritualizing Technology 168 Tugendhat House: An Elevated Personal Life 182 Neue Wache: In the World and Against It 194 Bauhaus Education 210 Reichsbank: In Dark Times Organic Architecture 232 Resor House: Autonomy 244 AIT/IIT: Open Campus 258 IIT: Clear Construction Unfolding Structure 282 Farnsworth to Crown Hall: Clear Span 314 860–880 Lake Shore Drive: High Rise 338 Seagram Building: Dark Building 364 50 x 50 House to New National Gallery: Variations and Permutations 400 Lafayette Park: City Landscape 444 Event Space: Living Life Large 468 Notes 506 Bibliography 530 Index 007 Ludwig Mies, Riehl House, Potsdam-Neubabelsberg, 1906–7; entrance from the upper walled garden 008 Ludwig Mies at the Riehl house, ca.1912 008 007 In 1906 Bruno Paul recommended Mies to the philosopher Alois Riehl Whereas the neighbouring villas were built as Italian or German Re- became the locus for an alternative way of life. Critical of placing Riehl House: Country and his wife, Sophie, who were looking to build a quiet house for naissance icons set within miniature picturesque gardens, the Riehl houses as features in the centre of their lots and treating the garden summers, weekends and their imminent retirement in the fashionable House was designed by Mies as a simple neo-Biedermeier block as a residual fragment of a picturesque landscape, Muthesius argued Berlin suburb of Potsdam-Neubabelsberg 008.