9. Bharati Bharali-Assamese Cinematic Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P. Anbarasan, M.Phil, Phd. Associate Professor Department of Mass Communication and Journalism Tezpur University Tezpur – 784028

P. Anbarasan, M.Phil, PhD. Associate Professor Department of Mass communication and Journalism Tezpur University Tezpur – 784028. Assam. [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: +91-9435381043 A Brief Profile Dr. P. Anbarasan is Associate Professor in the Dept. of Mass Communication and Journalism of Tezpur Central University. He has been teaching media and communication for the last 15 years. He specializes in film studies, culture & communication studies, and international communication. He has done his doctorate from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Earlier he had studied in University Madras and Bangalore University. Before becoming teacher he worked in All India Radio and some newspapers. He has published books on Gulf war and European Radio European identity and Culture in addition to other culture and communication research works. His interest area is media and the marginalized. 1 Work Presently Associate Professor in Mass Communication and Experience Journalism, at Tezpur central University since March 2005. Earlier worked as Lecturer in the Department of Mass communication & Journalism, Assam University, Silchar, Assam from September 2000 to March 2005. Prior to that worked as Junior officer of the Indian Information Service, from 1995 to 2000 and was posted at the Central Monitoring Service, New Delhi ( March 1995 to Sept. 2000). 2 Education Obtained PhD from at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi on the topic: “The European Union’s Cultural and Audiovisual Policy: A Discourse towards Integration beyond Borders” in 2012. Earlier completed M Phil in 1997 at Jawaharlal Nehru University on a topic, “Gulf Crisis and European Media: A study of Radio coverage and Its Impact”. -

Assamese Children Literature: an Introductory Study

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(4): 91-97 Article Received: 08th October, 2020; Article Revised: 15th February, 2021; Article Accepted: 20th March, 2021 Assamese Children Literature: An Introductory Study Dalimi Pathak Assistant Professor Sonapur College, Sonapur, Assam, India _________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION : Out of these, she has again shown the children Among the different branches of literature, literature of ancient Assam by dividing it into children literature is a remarkable one. Literature different parts, such as : written in this category for the purpose of the (A) Ancient Assam's Children Literature : children's well being, helps them to raise their (a) Folk literature level children literature mental health, intellectual, emotional, social and (b) Vaishnav Era's children literature moral feelings. Not just only the children's but a real (c) Shankar literature of the later period children's literature touches everyone's heart and (d) Pre-Independence period children literature gives immense happiness. Composing child's Based on the views of both the above literature is a complicated task. This class of mentioned researchers Assamese children literature exist in different languages all over the literature can be broadly divided into three major world. In our Assamese language too multiple levels : numbers of children literature are composed. (A) Assamese Children Literature of the Oral Era. While aiming towards the infant mind and mixing (B) Assamese Children Literature of the Vaishnav the mental intelligence of those kids with their Era. wisdom instinct, imagination and feelings, (C) Assamese Children Literature of the Modern literature in this category will also find a place on Era. the mind of the infants. -

Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia: a Versatile Legend of Assam

PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 DR. BHABENDRA NATH SAIKIA: A VERSATILE LEGEND OF ASSAM NilakshiDeka1 Prarthana Dutta2 1 Research Scholar, Department of Assamese, MSSV, Nagaon. 2 Ex - student, Department of Assamese, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh. Abstract:The versatile personality is generally used to refer to individuals with multitalented with different areas. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was one of the greatest legends of Assam. This multi-faceted personality has given his tits and bits to both the Assamese literature, as well as, Assamese cinema. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was winner of Sahitya Academy award and Padma shri, student of science, researcher, physicist, editor, short story writer and film director from Assam. His gift to the Assamese society and in the fields of art, culture and literature has not yet been adequately measured.Saikia was a genius person of exceptional intellectual creative power or other natural ability or tendency. In this paper, author analyses the multi dimension of BhabendraNathSaikias and his outstanding contributions to make him a versatile legendary of Assam. Keywords: versatile, legend, cinema, literature, writer. 1. METHODOLOGY During the research it collected data through secondary sources like various Books, E-books, Articles, and Internet etc. 2. INTRODUCTION BhabendraNathSaikia was an extraordinary talented genius ever produced by Assam in centuries. Whether it is literature or cinema, researcher or academician, VOLUME 11 ISSUE 9 2020 http://www.proteusresearch.org/ Page No: 401 PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 BhabendraNathSaikia was unbeatable throughout his life. The one name that coinsures up a feeling of warmth in every Assamese heart is that of Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia. 3. EARLY LIFE, EDUCATION AND CAREER BhabendranathSaikia was born on February 20, 1932, in Nagaon, Assam. -

A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema

A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema INDRANI BHARADWAJ Registered Number: 1424030 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication and Media Studies CHRIST UNIVERSITY Bengaluru 2016 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Media Studies ii CHRIST UNIVERSITY Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Indrani Bharadwaj Registered Number: 1424030 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ [AASITA BALI] _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ iii iv I, Indrani Bharadwaj, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: v vi CHRIST UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema Indrani Bharadwaj The following study deals with the relationship between Assamese Cinema and its connection to Italian Neorealism. Assamese Cinema was founded in 1935 when Jyoti Prasad Agarwala released his first film “Joymoti”. -

Print This Article

The world of Assamese celluloid: ‘yesterday and today’ Violet Barman Deka, Delhi University, [email protected] Volume 9. 1 (2021) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2021.358 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The study explores the entire journey of the Assamese cinema, which means a journey that will narrate many stories from its past and present, furthermore also will try to analyze its future potential. This paper deals with the trends emerging in genres, technical advancement, and visual representation along with a cult that emphasized the commercial success of cinema by toeing the style of Bollywood and world cinema. It explores the new journey of Assamese cinema, which deals with small budgets, realistic approaches, and portraying stories from the native lanes. It also touches upon the phase of ‘freeze’ that the Assamese cinema industry was undergoing due to global pandemic Covid-19. Keywords: Assamese cinema; Regional cinema; Jyotiprasad Agarwala; Regional filmmaker; Covid-19; OTT platform New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press The world of Assamese celluloid: ‘yesterday and today’ Voilet Barman Deka Introduction Is there any transformation in the craft of Assamese cinema or it is the same as it was in its beginning phase? Being a regional cinema industry, has the Assamese cinema been able to make its space in the creative catalog of Indian and world cinema? Is there anything radical that it has contributed towards the current and the next generation who is accepting and appreciating experimental cinema? This paper aims to explore the elongated journey of the Assamese cinema, a journey that will narrate many stories from its past and present as well analyze its future potential. -

Signed Mou of Assam State Film (Finance & Development) Corpn Ltd..Pdf

signed-mou-asf_fd_cl MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING (M o U) BETWEEN ASSAM STATE FILM (F INANCE & DEVELOPMENT ) C ORPORATION LTD . AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT Government of Assam For the Financial Year 2006-07 signed-mou-asf_fd_cl PREAMBLE The Assam State Film (Finance and Development) Corporation Ltd. was incorporated on 4 th September, 1974 with an Authorized Share Capital of Rupees Ten Lakh only with 1000 equity Shares @ Rs.1000.00 each. The Corporation was registered under the Companies Act, 1956. The Corporation has staff strength of eleven employees excluding the Managing Director. The Corporation is engaged in financing Loan to the Producers of Asomiya Films, organizing Film Festivals and Film appreciation Courses for encouragement of Assamese Film Lovers and has been trying to focus the rich Cultural heritage to the rest of our Country through this media. MISSION Promotion of Asomiya Film Industry & also widely acclaimed non-Asomiya Films along with preservation of cultural heritage. OBJECTIVES 1. To finance production of Assamese Films by advancing loans, subsidies, grants etc. or by extending financial assistance in any other related matter. 2. To encourage, foster, aid establish and maintain institutions for imparting knowledge and instructions on all matters connected with and allied to Film Industry. 3. To carry on the business of production of Films. 4. To carry on the business of financers, producers, distributors, exhibitors, agents of cinema Films and other allied Industry. 5. To construct, run and manage Cinema Show House, Theatre Halls, auditoriums etc. on modern line. 6. To give awards, subsidies and to hold film festivals etc, for the improvement and encouragement of better quality Films. -

Contributions of Women's to 20 Century Assamese Novel

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 05, 2020 Contributions of Women’s To 20th Century Assamese Novel Gyanshree Dutta Research Scholar, Department of Assamese, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh, Assam, India Abstract A healthy society is being formed by the equal efforts of men and women. Contributions of both are important to create a real society. In country like India, women in parallel with man faced difficulties in the old days. But now it is seen to be the opposite. Now a days both men and women are bringing pride to the country by achieving a high level of success. In this way in the context of the North-East India, women’s of Assam have significant contributions to Assamese literature along with the various aspects of knowledge, Cultures, Science etc. This study attempts to discuss contributions of women’s to the Assamese Novel of the 20th century. Keyword : 20th century Assamese novel, women’s contributions, women’s views. 0.0 Introduction : Women’s have been facing difficulties in moving forward in parallel with men in society since ancient times. In this way, the skills that previously Assamese women had shown in the social, cultural field; in addition to the entire responsibility of children and families were not socially recognized. Rather than women were tied up with some religious discipline. But reforms the 19th century, the circulation of female education under the initiative of missionary in Assam changed the previous tradition for women. In the light of education Assamese women were able to establish their own in all social fields by gradually expanding their family ties. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 15 March Final.Pdf

INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE 2015-2016 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Prof. M.G.K. Menon Mr. Vipin Malik Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. R.K. Pachauri Mr. N.N. Vohra Executive Committee Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, Chairman Mr. K.N. Rai Air Marshal Naresh Verma (Retd.), Director Mr. Suhas Borker Cmde. Ravinder Datta, Secretary Smt. Shanta Sarbjeet Singh Mr. Dhirendra Swarup, Hony. Treasurer Dr. Surajit Mitra Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. U.D. Choubey Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Chairman Air Marshal Naresh Verma (Retd.), Director Dr. U.D. Choubey Cmde. Ravinder Datta, Secretary Mr. Rajarangamani Gopalan Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, CFO Mr. Dhirendra Swarup, Hony. Treasurer Medical Consultants Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. Mohammad Qasim Dr. Gita Prakash IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance & Accounts Officer Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Rajiv Mohan Mehta, Manager, Catering Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Annual Report 2015–2016 This is the 55th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February 2015 to 31 January 2016. It will be placed before the 60th Annual General Body Meeting of the Centre, to be held on 31 March 2016. Elections to the Executive Committee and the Board of Trustees of the Centre for the two-year period, 2015–2017, were initiated in the latter half of 2014. -

Selected List

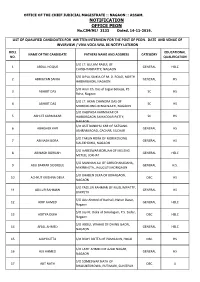

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE :: NAGAON :: ASSAM. NOTIFICATION OFFICE PEON No.CJM(N)/ 3133 Dated, 14-11-2019. LIST OF QUALIFIED CANDIDATES FOR WRITTEN INTERVIEW FOR THE POST OF PEON. DATE AND VENUE OF INVERVIEW / VIVA VOCA WILL BE NOTIFY LATERON ROLL EDUCATIONAL NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHERS NAME AND ADDRESS CATEGORY NO. QUALIFICATION S/O LT. GULAM RASUL OF 1 ABDUL HOQUE GENERAL HSLC CHRISHTANPATTY, NAGAON S/O BIPUL SAIKIA OF M. D. ROAD, NORTH 2 ABHIGYAN SAIKIA GENERAL HS HAIBARGAON, NAGAON S/O Arun Ch. Das of Jagial Bebejia, PS. 3 ABHIJIT DAS SC HS Raha, Nagaon S/O LT. AKAN CHANDRA DAS OF 4 ABHIJIT DAS SC HS MORIKOLONG BENGENAATI, NAGAON S/O KALIPADA KARMAKAR OF 5 ABHIJIT KARMAKAR HAIBORGAON SAMADDAR PATTY, SC HS NAGAON S/O ASIT BANDHU KAR OF SATSANG 6 ABHISHEK KAR GENERAL HS ASHRAM ROAD, CACHAR, SILCHAR S/O TARUN BORA OF MORIKOLONG 7 ABINASH BORA GENERAL HS SIALEKHOWA, NAGAON S/O HARESWAR BORUAH OF MELENG 8 ABINASH BORUAH GENERAL HSLC METELI, JORHAT S/O MANNAN ALI OF SARUCHAKADAHA, 9 ABU BAKKAR SIDDIQUE GENERAL H.S. MIKIRBHETA, JALUGUTI,MORIGAON S/O BHABEN DEKA OF BORAGAON, 10 ACHYUT KRISHNA DEKA OBC HS NAGAON S/O FAZILUR RAHMAN OF MUSLIMPATTY, 11 ADILUR RAHMAN GENERAL HS BARPETA S/O Aziz Ahmed of Itachali, Natun Bazar, 12 ADIP AHMED GENERAL HSLC Nagaon S/O Joy Kt. Deka of Simaluguri, P.S. Sadar, 13 ADITYA DEKA OBC HSLC Nagaon S/O ABDUL WAHAB OF DHING GAON, 14 AFJAL AHMED GENERAL HSLC NAGAON 15 AJAY DUTTA S/O BIJOY DUTTA OF PAMGAON, HOJAI OBC HS S/O LATIF AHMED OF AZAD NAGAR, 16 AJIJ AHMED GENERAL HS NAGAON S/O SOMESWAR NATH OF 17 AJIT NATH OBC X BHALUKEKHOWA, PUTIMARI, SUNITPUR S/O TITARAM PANGGING OF SONARI, 18 AJOY PANGGING STP HS CHARAIDEO S/O LT AKON BORAH OF GHAGRAPARA 19 AKANTA BORAH OBC HS CHUBURI, SONITPUR S/O LT PRAFULLA LASKAR OF BARKOLA, 20 AKASH LASKAR OBC HSLC NAGAON S/O Girish Raja of Pub Solmara, P.S. -

Assamese Poetry (1889-2015) Credits: 4 = 3+1+0 (48 Lectures)

P.G. 2nd Semester Paper: ASM801C (Core) Assamese Poetry (1889-2015) Credits: 4 = 3+1+0 (48 Lectures) Objective: The romantic trend of Assamese poetry as initiated by the jonaki in 1889 continued more or less upto 1939. The socio-economic-political changes brought about by the Second World War and India’s independence added new tone and tenor to Assamese poetry. In contemporary times, myriad factors have deeply influenced Assamese poetry thereby giving to it a separate character. This Course is expected to familiarize the students with this history of Assamese poetry by way of considering some select poems of the representative Assamese poets of the period in question. Unit I : Romantic Poetry (First Wave) Lakshminath Bezbaroa Priyatama Padmanath Gohain Baruah Milan-Mahatva Chandradhar Baruah Smriti Unit II : Romantic Poetry (Second Wave) Ambikagiri Roychoudhury Ki Layanu Dila Mok Nalinibala Devi Natghar Ananda Chandra Barua Prithibir Preme Mok Dewaliya Karile Unit III : Modern Poetry Hem Barua Yatrar Shesh Nai Navakanta Barua Bodhidrumar Khari Ajit Barua Chenar Parat Nilamoni Phukan Alop Agote Aami Ki Kotha Pati Aachilo Bireswar Barua Anek Manuh Anek Thai Aru Nirjanata Unit IV : Modern Poetry (Contemporary) Gyan Pujari Aakal Shirshak Rafikul Hossain Ratir Boragi Anupama Basumatary Machmariyar Sadhu Jiban Narah Rong Reference Books Assamese Asamiya Kabitar Kahini : Bhabananda Dutta Asamiya Kabitar Bisar-Bishleshan : Archana Puzari (ed.) Asamiya Kabita : Karabi Deka Hazarika Adhunik Asamiya Kabitar Tinita Stwar : Malini Goswami & Kamaluddin -

E-Newsletter

DELHI hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh a large number of languages in India, and we have lots BHASHA SAMMAN of literature in those languages. Akademi is taking April 25, 2017, Vijayawada more responsibility to publish valuable literature in all languages. After that he presented Bhasha Samman to Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao, Prof. T.R Damodaran and Smt. T.S Saroja Sundararajan. Later the Awardees responded. Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao expressed his gratitude towards the Akademi for the presentation of the Bhasha Samman. He said that among the old poets Mahakavai Tikkana is his favourite. In his writings one can see the panoramic picture of Telugu Language both in usage and expression. He expressed his thanks to Sivalenka Sambhu Prasad and Narla Venkateswararao for their encouragement. Prof. Damodaran briefed the gathering about the Sourashtra dialect, how it migrated from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu and how the Recipients of Bhasha Samman with the President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi cultural of the dialect has survived thousands of years. He expressed his gratitude to Sahitya Akademi for Sahitya Akademi organised the presentation of Bhasha honouring his mother tongue, Sourashtra. He said Samman on April 25, 2017 at Siddhartha College of that the Ramayana, Jayadeva Ashtapathi, Bhagavath Arts and Science, Siddhartha Nagar, Vijayawada, Geetha and several books were translated into Andhra Pradesh. Sahitya Akademi felt that in a Sourashtra. Smt. T.S. Saroja Sundararajan expressed multilingual country like India, it was necessary to her happiness at being felicitated as Sourashtrian. She extend its activities beyond the recognized languages talked about the evaluation of Sourashtra language by promoting literary activities like creativity and and literature. -

South Asian Film & Television 16 + Guide

SOUTH ASIAN FILM & TELEVISION 16 + GUIDE www.bfi.org.uk/imagineasia This and other bfi National Library 16+ guides are available from http://www.bfi.org.uk/16+ IMAGINEASIA - SOUTH ASIAN FILM & TELEVISION Contents Page IMPORTANT NOTE ........................................................................................ 1 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................. 2 APPROACHES TO RESEARCH, by Samantha Bakhurst.................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 6 BANGLADESH............................................................................................... 7 Focus on Filmmakers: Zahir Raihan................................................................. 9 BHUTAN, NEPAL & TIBET.............................................................................. 9 PAKISTAN..................................................................................................... 10 Focus on Filmmakers: Jamil Dehlavi ................................................................ 16 SRI LANKA .................................................................................................... 17 Focus on Filmmakers: Lester James Peries ..................................................... 20 INDIA · General References............................................................................ 22 · Culture, Society and Film Theory ......................................................... 33 · Film