Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSIDE the Prabhakhaitanfoundationchronicle Their Musicto Life Words to Bring Melodies in Authors String on Musiciansas World Ofbooks Dive Into the POETRY of LIFE 14

The Prabha Khaitan Foundation Chronicle January 2020 I Issue 10 Dive into the world of books on musicians as authors string melodies in words to bring their music to life POETRY OF HINGLISH ROMANCE IS LIFE BABU WRITE 14 15 13 INSIDE 2 INSIDE MITHILA Music, Memories STORIES 18 and More “If winter comes, can spring be far behind?” — GAMECHANGER Percy Bysshe Shelley. LAUNCH Spring has definitely arrived, bringing with it renewed zeal and spirit, and the Foundation 20 has been taking advantage of the same. It has been our constant endeavour to feature new writers and showcase new genres and WINNING narratives. And like spring, our bouquet of literary events also embodied the new — both WOMAN in terms of essence and faces. Music was the flavour of the season. We 26 have been privileged to host some of the greatest luminaries from the world of music. Their stories unveiled the ordinary behind the A ROOM WITH A extraordinary legends of timeless melodies. Sessions featured maestros of classical music, VIEW stalwarts of the Bollywood music industry, music queens who broke all stereotypes 34 and more. While their stories awed us, their words humbled us. Hope you enjoy reading MANISHA JAIN the extraordinary tales of some of the best of Communications & Branding Chief, music. CAUSE OF THE Prabha Khaitan Foundation Alongside putting together our regular MONTH events, we are busy gearing up for the Ehsaas Conclave. The mantra of the Conclave is 38 ‘Learning, Linking and Leadership.’ Ehsaas Women from all over India and abroad will be coming together at the conclave to bond CELEBRATING over ideas and experiences. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Special Conference Issue (Vol. 12, No. 5, 2020. 1-11) from 1st Rupkatha International Open Conference on Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Humanities (rioc.rupkatha.com) Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n5/rioc1s17n3.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s17n3 Identity, Indigeneity and Excluded Region: In the Quest for an Intellectual History of Modern Assam Suranjana Barua1 & L. David Lal2 1Assistant Professor in Linguistics, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Information Technology Guwahati, Assam, India. Email: [email protected] 2Assistant Professor in Political Science, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Information Technology Guwahati, Assam, India. Email: [email protected] Abstract If Indian intellectual history focussed on the nature of the colonial and post-colonial state, its interaction with everyday politics, its emerging society and operation of its economy, then how much did/ does North- East appear in this process of doing intellectual history? North-East history in general and its intellectual history in particular is an unpeopled place. In Indian social science literature, North-East history for the last seventy years has mostly revolved around separatist movements, insurgencies, borderland issue and trans- national migration. However, it seldom focussed on the intellectuals who have articulated the voice of this place and constructed an intellectual history of this region. This paper attempts to explore the intellectual history of Assam through understanding the life history of three key socio-political figures – Gopinath Bordoloi, Bishnu Prasad Rabha and Chandraprabha Saikiani. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Abbas, Haider

AUTHOR INDEX, 2012 Abbas, Haider: Will Mulayam Checkmate Ahlawat, Neerja: The Political Economy of Congress? (LE) Haryana's Khaps (C) Issue no: 09, Mar 03-09, p.5 Issue no: 47-48, Dec 01-13, p.15 Abhinandan, T A et al: Suppression of Ahmad, Nesar: See Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala Constitutional Rights (LE) Issue no: 17, Apr 28-May 04, p.5 Ahmad, Shakeel: See Singh, K P Abodh Kumar; Neeraj Hatekar and Rajani Ahmed, Imtiaz: Teesta, Tipaimukh and River Mathur: Paanwalas in Mumbai: Property Linking: Danger to Bangladesh-India Rights, Social Capital and Informal Relations (F) Sector Livelihood (F) Issue no: 16, Apr 21-27, p.51 Issue no: 38, Sep 22-28, p.90 Ahmed, Mokbul M: See Vishwanathan, P K Acharya, Rajib; Shagun Sabarwal and Shireen J Jejeebhoy: Women's Aiyar, Suranya: The Child and the Family Empowerment and Forced Sex Within (LE) Marriage in Rural India (SA) Issue no: 12, Mar 25-31, p.4 Issue no: 02, Jan 14-20, p.65 Ajay Kumar: Khap Panchayats: A Adams, Bill: See Vira, Bhaskar Socio-Historical Overview (RA) Issue no: 04, Jan 28 - Feb 03, p.59 Adhikary, Sourav: Consolidating Religio-Political Forces (LE) -: Misrepresentation of Authors Issue no: 19, May 12-18, p.5 Views (LE) Issue no: 06, Feb 11-17, p.4 Adve, Nagraj: A Prolonged Enquiry (BR) Issue no: 32, Aug 11-17, p.35 Ajit, D: See Saxena, Ravi Agarwal, Ravi: E-Waste Law: New Paradigm Akhter, Majed: The Politics of Or Business as Usual? (C) Sovereignty in Pakistan (C) Issue no: 25, Jun 23-29, p.14 Issue no: 02, Jan 14-20, p.17 Aggarwal, Ankita; Ankit Kumar and Aashish Akolgo, Bishop; Raina -

Space Exploration's Next Frontier

Tuesday, June 16, 2020 Shawwal 24, 1441 AH Doha today: 330 - 450 The future Space exploration’s next frontier: Remote-controlled robonauts. P4-5 COVER STORY HOLLYWOOD BACK PAGE White celebs rush to Artists laud Qatar’s resilience amplify Black Lives Matter. during unjust blockade. Page 15 Page 16 2 GULF TIMES Tuesday, June 16, 2020 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT SERIES TO BINGE WATCH ON AMAZON PRIME PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.12am Shorooq (sunrise) 4.45am Zuhr (noon) 11.36am Asr (afternoon) 2.59pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.27pm Isha (night) 7.57pm USEFUL NUMBERS Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Modern Love been a date. An unconventional new family. These are unique Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 CAST: Anne Hathaway, Tina Fey, Andy Garcia stories about the joys and tribulations of love, each inspired Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 SYNOPSIS: An unlikely friendship. A lost love resurfaced. by a real-life personal essay from the beloved New York Times 44593363 A marriage at its turning point. A date that might not have column Modern Love. Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post – General Postal Corporation 44464444 Humanitarian Services Office (Single window facility for the repatriation of bodies) Ministry of Interior 40253371, 40253372, 40253369 Ministry of Health 40253370, 40253364 Hamad Medical Corporation 40253368, 40253365 Qatar Airways 40253374 ote Unquo Qu te “Childhood is a short season.” — Helen Haye The Expanse to find a missing young woman; Julie between Earth, Mars and The Belt. -

Gulabo Sitabo’: Satire Served with Real Lakhnavi Wit “Gulabo Sitabo” (Stream- Tle

B-8 | Friday, June 19, 2020 BOLLYWOOD www.WeeklyVoice.com ‘Gulabo Sitabo’: Satire Served With Real Lakhnavi Wit “Gulabo Sitabo” (stream- tle. Gulabo-Sitabo are traditional would draw your sympathy at the ing on Amazon Prime); Cast: glove puppets of Uttar Pradesh. irst glance, only to incite aver- Amitabh Bachchan, Ayushmann Sitabo is the overworked spouse sion the moment you fathom his Khurrana, Vijay Raaz, Brijendra while and Gulabo the smart par- unabashed greed.. Kala, Srishti Shrivastava, Far- amour who mostly knows how to It must have been a mammoth rukh Jafar; Direction: Shoojit get her way for nothing. task for Ayushmann Khurrana to Sircar; Rating: * * * (three stars) In the ilm, Amitabh Bachchan stand up to such a formidable act is cast as the haggard old Mirza, but the new-generation star sim- By Vinayak Chakravorty obsessed about shielding his ply brings out his best. mansion from a series of people He lives out the atta chakki- First thing, “Gulabo Sitabo” is who have a shark’s gaze on the waala Bankey only too authenti- positioned as a comedy but the sprawling but crumbling proper- cally, down to a heartland accent ilm would not fulil deinition of ty. Ayushmann Khurrana is Ban- highlighted by a lisp, and supple- the genre in the traditional Bolly- key, one of Mirza’s tenants who mented by the right physical at- wood sense. This is not irst day- has not paid rent (a princely sum tributes. irst show LOL stuff, and it would of Rs 30) for months. Mirza and Bankey’s show- seem a prudent move to launch Without giving away spoilers, Scene from ‘Gulabo Sitabo’ down sequences are the ilm’s this reined whiff on OTT. -

D8A4 E` Ac`SV ?R \R R Reert\

'* ; "<%"= %"== !" RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 /* 01 2 /!") " # $%& !" !"#$% &$' * 3) ) 34 5)6.33..3 . ) 36 +8 &!&'#(%') )'# ..-8) .3 5) )' !)'# ') , 384 ,.9) 3).) . ))3*75 ** )' !#* )'&' +'*%' ' # $%& ' '(%)*)*+ , -": - .-/ rapes and violence for decades meet Pakistan’s Punjab and the Nankana incident Governor and Chief Minister,” shows how minorities there are he said. Longowal said the del- persecuted and why they need egation will comprise Rajinder citizenship in India. Singh Mehta, Roop Singh, Lekhi also said that this Surjit Singh and Rajinder incident should open the eyes Singh. !"" of Congress leaders such as So- “We have spoken with the nia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and Gurdwara Nankana Sahib Q ))*+ no borders. Navjot Singh Sidhu, TMC sup- management committee...They Taking to Twitter, Rahul remo Mamata Banerjee, the told us the situation is normal ! he Shiromani Gurdwara termed Friday attack repre- leftists and the “Urban Naxals” now,” Longowal said. # $% TParbhandhak Committee hensible, and said the only who have been opposing the The SGPC chief said the &'() +L (SGPC), the apex body which known antidote to bigotry is amended Citizenship Act. sentiments of the Sikh com- *,- provincial authorities in the - manages Sikh shrines, will love, mutual respect and under- Meanwhile, strongly con- munity were hurt with the Punjab province have informed L send a four-member delegation -

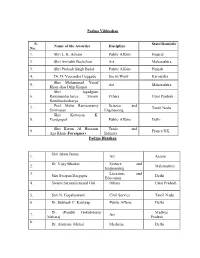

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

Assamese Children Literature: an Introductory Study

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(4): 91-97 Article Received: 08th October, 2020; Article Revised: 15th February, 2021; Article Accepted: 20th March, 2021 Assamese Children Literature: An Introductory Study Dalimi Pathak Assistant Professor Sonapur College, Sonapur, Assam, India _________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION : Out of these, she has again shown the children Among the different branches of literature, literature of ancient Assam by dividing it into children literature is a remarkable one. Literature different parts, such as : written in this category for the purpose of the (A) Ancient Assam's Children Literature : children's well being, helps them to raise their (a) Folk literature level children literature mental health, intellectual, emotional, social and (b) Vaishnav Era's children literature moral feelings. Not just only the children's but a real (c) Shankar literature of the later period children's literature touches everyone's heart and (d) Pre-Independence period children literature gives immense happiness. Composing child's Based on the views of both the above literature is a complicated task. This class of mentioned researchers Assamese children literature exist in different languages all over the literature can be broadly divided into three major world. In our Assamese language too multiple levels : numbers of children literature are composed. (A) Assamese Children Literature of the Oral Era. While aiming towards the infant mind and mixing (B) Assamese Children Literature of the Vaishnav the mental intelligence of those kids with their Era. wisdom instinct, imagination and feelings, (C) Assamese Children Literature of the Modern literature in this category will also find a place on Era. the mind of the infants. -

October 26, 2017 Enquiries

VOL 11 ISSUE 42 ● NEW YORK/DALLAS ● OCTOBER 20 - OCTOBER 26, 2017 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 THE INDIAN PANORAMA 2 ADVERTISEMENT FRIDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2017 www.theindianpanorama.news VOL 11 ISSUE 42 ● NEW YORK/DALLAS ● OCTOBER 20 - OCTOBER 26, 2017 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 No second coming for A NEW DAWN FOR Diwali stood for Hindu- Australian Senate rejects Anna: A bogus morality is THE CONGRESS Muslim solidarity in the proposed visa, citizenship 8 dangerous 9 PARTY IN PUNJAB 16 Mughal era 23 curbs India and US have a "Natural, Instinctive Relationship", says President Trump Celebrates Diwali at White Ambassador Chakravorty House; Praises India, Indian Americans WASHINGTON (TIP): Following in the footsteps of his predecessor Barak Obama, President Trump himself led from the front by hosting a Diwali celebration in the White House on October 17. In his first Diwali Taking questions at the IACC reception to Ambassador Sandeep Chakravorty on October 17. celebration in the Oval Office From L to R: Consul L Krishnamurthy, IACC President of the White House, Trump Rajiv Khanna and Ambassador Sandeep Chakravorty was accompanied by senior Photo / Bidisha Roy Indian-American members of the administration, Bidisha Roy including US Ambassador to NEW YORK CITY (TIP): The India-America Chamber of the UN Nikki Haley, Seema Commerce (IACC) hosted a reception on October 17, 2017 to Verma, administrator of welcomeAmbassador Sandeep Chakravorty, India's Consul Centers for Medicare and General in New York. In his welcome address IACC President Medicaid Services, Ajit Pai, Rajiv Khanna pointed out that India's relations with the Chairman of the US Federal United States are at a critical juncture and Ambassador Communications Chakravorty would be a key person to strengthen the bilateral Commission and Raj Shah, relationship. -

Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia: a Versatile Legend of Assam

PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 DR. BHABENDRA NATH SAIKIA: A VERSATILE LEGEND OF ASSAM NilakshiDeka1 Prarthana Dutta2 1 Research Scholar, Department of Assamese, MSSV, Nagaon. 2 Ex - student, Department of Assamese, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh. Abstract:The versatile personality is generally used to refer to individuals with multitalented with different areas. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was one of the greatest legends of Assam. This multi-faceted personality has given his tits and bits to both the Assamese literature, as well as, Assamese cinema. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was winner of Sahitya Academy award and Padma shri, student of science, researcher, physicist, editor, short story writer and film director from Assam. His gift to the Assamese society and in the fields of art, culture and literature has not yet been adequately measured.Saikia was a genius person of exceptional intellectual creative power or other natural ability or tendency. In this paper, author analyses the multi dimension of BhabendraNathSaikias and his outstanding contributions to make him a versatile legendary of Assam. Keywords: versatile, legend, cinema, literature, writer. 1. METHODOLOGY During the research it collected data through secondary sources like various Books, E-books, Articles, and Internet etc. 2. INTRODUCTION BhabendraNathSaikia was an extraordinary talented genius ever produced by Assam in centuries. Whether it is literature or cinema, researcher or academician, VOLUME 11 ISSUE 9 2020 http://www.proteusresearch.org/ Page No: 401 PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 BhabendraNathSaikia was unbeatable throughout his life. The one name that coinsures up a feeling of warmth in every Assamese heart is that of Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia. 3. EARLY LIFE, EDUCATION AND CAREER BhabendranathSaikia was born on February 20, 1932, in Nagaon, Assam. -

Lakshmi Full Movie 720P

Lakshmi Full Movie 720p 1 / 4 2 / 4 Lakshmi Full Movie 720p 3 / 4 Option 2 Torrent 1.1 GB Hindi HD 720p; Lakshmi Bomb 2018 HD Hindi Dubbed 800MB . WorldFree4u.com. 300mb Movies Download .... Prabhu Deva and Ditya Bhande in Lakshmi Dance Movies, All Movies, Movie Songs,.. 21-Jan-2020 - Lakshmi (2018) Tamil 720p Real DVDScr [1.2 GB] Full Tamil Movie.. You can watch this Movie hd free Lakshmi Bomb Hindi .... Watch Lakshmi (2018) full movie online in HD. Enjoy this Drama film starring Sam Paul:Channel 99 Head,Karunakaran:Azhagu (Krishna's Cafe Worker),Jeet .... My Hindi debut direction movie Laxmi is releasing in #Disneyplushotstar at 7.05 pm today. Through Tamil movie Kanchana, I wanted to convey .... Based on true events, Lakshmi is a story of heroism and untold courage. Lakshmi, a 13 year old girl is kidnapped and sold into prostitution.. Laxmi Bomb movie download in 720p/480p leaked by tamilrockers tamilyogi filmyap: ... Laxmii Movie Download Leaked by Tamilrockers in Hd.. 787 Web TORRENT JOKER 2019 movie download full HD 720p Hindi ... Bomb Movie Download Laxmmi Bomb Full Movie Download Laxmi Bomb movie.. Lakshmi Movie Online Watch Lakshmi Full Length HD Movie Online on YuppFlix. Lakshmi Film Directed by A L Vijay Cast Prabhu Deva, Ditya Bhande, .... Laxmi Bomb Full Movie Download 720p 480P by Pagalworld. Laxmi Bomb Full Movie Download: Laxmi Bomb Full Movie Download is a film .... Background music credit : NCS Download Link of Laxmi Movie http://dl.videoohot.com/su/haqjUT50Subscribe the channel and press the bell .... Laxmii Full HD Available For Free Download Online on Tamilrockers And Other Torrent Sites.