Iyengar's Sitayana: a Retelling of the Saga of Sita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Phase-II), Bihar Under RAY 1: Name of Slum:- New Ambedkar Colony

DPR for construction of 1061 DUs at Patna (Phase-II), Bihar under RAY 1: Name of Slum:- New Ambedkar Colony (Sandalpur) Sr.No Name Of Beneficiary Father/Husband's name 1 Manorma Devi Hari Manjhi 2 Manju Devi Bhunesabar Das 3 Mala Devi Hemnt Ram 4 Lalati Devi Mukundas Ravi Das 5 Rajani Devi Sajay Prasad 6 Sumitra Devi Jagdesh Chaudhari 7 Punam Devi Surendra Ram 8 Chonhi Maham Sattan 9 Hema Devi Shiv Ram 10 Sona Devi Raju Chaudhari 11 Sushila Devi Vipin Rout 12 Poonam Devi Rajesh Ram 13 Shyamsundri Devi Kalichran 14 Renu Devi Late Ajay Chaudhari 15 Pinki Devi Bikki Chaudhari 16 Shakuntala Devi Tuntun Ram 17 Rinki Devi Jay Kumar 18 Kiran Devi Santosh Ram 19 Mamta Devi Ashok Das 20 Gunja Devi Prem Ram 21 Anisha Khatoon Late Md Shafique 22 Sangeeta Devi Kundan Ram 23 Chanda Devi Munna Chaudhari 24 Kiran Devi Surendra Rout 25 Amna Khatoon Md. Shamim 26 Babita Devi Sunil Kumar 27 Shila Devi Late Khagri Ram 28 Runi Devi Sanju Manjhi 29 Rina Devi Rajendra Sahani 30 Gulawasa Khatoon Md. Shahid 31 Salma Khatoon Md. Eadu 32 Sapana Devi Ravi Ram 33 Sabina Khatoon Md. Samsulak 34 Sakhandra Devi Late Ramchandra Das 35 Mariyam Khatoon Md. Golden 36 Sunita Devi Ganesh Ram 37 Amna Khatoon Md. Aslam 38 Soni Khatoon Md. Sahid 39 Fula Pati Devi Rambadan Das 40 Sakuntala Devi Ganesh Das 41 Neha Devi Raj Kumar Chaudhary 42 Nitu Devi Dilip Ram 43 Girish Devi Late Swaminath Raut 44 Pinki Devi Ranjit Ram 45 Bina Devi Binay Prasad 46 Mina Devi Ramanand Ram 47 Nilam Devi Suresh Ram 48 Gita Devi Late Santosh Ram 49 Reena Devi Rajesh Ram 50 Jully Devi Sambho Ram 51 Binita Devi Binod Kumar 52 Sumitra Devi Bindeshi Das 53 Laxmi Devi Shukhdeo Das 54 Asha Devi Suresh Ram 55 Radha Kumari Sanjay Kumar 56 Anita Kumari Deepu Kumar 57 Lalmuni Devi Late Raja Ram 58 Tarnnum Khatoon Md. -

A Case of the Possession Type in India with Evidence of Paranormal Knowledge

Journal o[Scic.icwt~fic.Explorulion. Vol. 3, No. I, pp. 8 1 - 10 1, 1989 0892-33 10189 $3.00+.00 Pergamon Press plc. Printed in the USA. 01989 Society for Scientific Exploration A Case of the Possession Type in India With Evidence of Paranormal Knowledge Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, University of Virginia, Charlottesvill~:VA 22908 Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, India 5epartment of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, Universily of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908 Abstract-A young married woman, Sumitra, in a village of northern India, apparently died and then revived. After a period of confusion she stated that she was one Shiva who had been murdered in another village. She gave enough details to permit verification of her statements, which corresponded to facts in the life of another young married woman called Shiva. Shiva had lived in a place about 100 km away, and she had died violently there-either by suicide or murder-about two months before Sumitra's apparent death and revival. Subsequently, Sumitra recognized 23 persons (in person or in photographs) known to Shiva. She also showed in several respects new behavior that accorded with Shiva's personality and attainments. For example, Shiva's family were Brahmins (high caste), whereas Sumitra's were Thakurs (second caste); after the change in her personality Sumitra showed Brahmin habits that were strange in her fam- ily. Extensive interviews with 53 informants satisfied the investigators that the families concerned had been, as they claimed, completely unknown to each other before the case developed and that Sumitra had had no normal knowledge of the people and events in Shiva's life. -

Ramakatha Rasavahini I Chapter 3

Chapter 3. Curse of No Progeny for Dasaratha The envy of Ravana ithin a short time, Dasaratha’s fame illumined all quarters, like the rays of the rising sun. He had the intre- Wpidity and skill of ten charioteers rolled into one, so the name Dasa-ratha (the ten-chariot hero) was found appropriate. No one could stand up against the onrush of his mighty chariot! Every contemporary ruler, mortally afraid of his prowess, paid homage to his throne. The world extolled him as a hero without equal, a paragon of virtue, a statesman of highest stature. Ravana, the demon (rakshasa) King of Lanka, heard of Dasaratha and his fame. He was so envious that he determined on a sure plan to destroy him, by means fair or foul. Ravana sought for an excuse to provoke Dasaratha into a fight; one day, he sent word through a messenger that unless tribute was paid to him, he would have to meet Ravana on the battlefield and demonstrate his superior might in war. This call was against international morality, but what morality did a demon respect? When Dasaratha heard the messenger, he laughed outright, in derision. Even while the messenger was look- ing on, he shot sharp deadly arrows, which reached Lanka itself and fastened the gates of that city! Addressing the envoys, Dasaratha said, “Well, Sirs! I have now made fast the doors of your fortress city. Prema Vahini Your master cannot open them, however hard he may try. That is the ‘tribute’ I pay to your impertinent lord.” When the envoys returned and informed Ravana of this, he was shocked to find all the doors closed fast. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks. -

Ramayana: a Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play As Scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Ramayana: A Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play as scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Volume I Compiled by Tumuluru Krishna Murty Edited by Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi © Tumuluru Krishna Murty ‘Anasuya’ C-66 Durgabai Deshmukh Colony Ahobil Mutt Road Hyderabad 500007 Ph: +91 (40) 2742 7083/ 8904 Typeset and formatted by: Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi Cover Designed by: Insty Print 2B, Ganesh Chandra Avenue Kolkata - 700013 Website: www.instyprint.in VOLUME I No one can shake truth; no one can install untruth. No one can understand My mystery. The best you can do is get immersed in it. The mysterious, indescribable power has come within the reach of all. No one is born and allowed to live for the sake of others. Each has their own burden to carry and lay down. - Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Put all your burdens on Me. I have come to bear it, so that you can devote yourselves to Sadhana TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME I PRAYERS 11 1. SAMARPANAM 17 2. EDITORIAL COMMENTS 27 3. THE ESSENCE OF RAMAYANA 31 4. IKSHVAKU DYNASTY-THE IMPERIAL LINE 81 5. DASARATHA AND HIS CONSORTS 117 118 5.1 DASARATHA 119 5.2 KAUSALYA 197 5.3 SUMITRA 239 5.4 KAIKEYI 261 INDEX 321 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1: DESCENT OF GANGA 113 FIGURE 2: PUTHRAKAMESHTI YAGA 139 FIGURE 3: RAMA TAKING LEAVE OF DASARATHA 181 FIGURE 4: DASARATHA SEES THE FATALLY INJURED SRAVANA 191 PRAYERS Vaamaankasthitha Jaanaki parilasat kodanda dandaamkare Chakram Chordhva karena bahu yugale samkham saram Dakshine Bibranam Jalajadi patri nayanam Bhadradri muurdhin sthitham Keyuradi vibhushitham Raghupathim Soumitri Yuktham Bhaje!! - Adi Sankara. -

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List S.no Town Name Father_Name Mobile_No Pres_Address_StreetName 1 Jalesar BABY YASH PAL SINGH 7451085904 MOHALLA AKBARPUR HAVELI, JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 2 Jalesar MOHAR SHRI DEVI HAKIM SINGH 8006820002 BHAAMPURI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 3 Jalesar VIPIL KUMAR CHANDARPAL 7534009766 MOHALLA AKABRPUR HAWELI V.P.O JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 4 Jalesar GUDDO BEGUM LAL KHAN 9568203120 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 5 Jalesar CHANDRVATI VIJAY SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 6 Jalesar POONAM BHARATI MIHALLA AKABARPUR 8869865536 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 7 Jalesar SAROJ KUMARI KUWARPAL SINGH 9690823309 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 8 Jalesar MOHAMMAD FAHIM MOHAMMAD SAHID 8272897234 MOHHALA KILA , JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 9 Jalesar SHAJIYA BEGAM BABLU 9758125174 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 10 Jalesar AMIT KUMAR DAU DAYAL BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 11 Jalesar KARAN SINGH LEELADHAR BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 12 Jalesar GUDDI NAHAR SINGH 9756578025 BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 13 Jalesar MADAN MOHAN PURAN SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 14 Jalesar KANTI MUKESH KUMAR 9027022124 MOHALLA BARHAMAN PURI JALESAR ETHA 15 Jalesar SOMATI DEVI BACHCHO SINGH 7906607313 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 16 Jalesar ANITA DEVI SATYA PRAKESH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 17 Jalesar VIRENDRA SINGH AMAR SINGH 7500511574 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, -

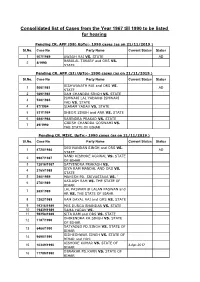

Consolidated List of Cases from the Year 1967 Till 1990 to Be Listed for Hearing

Consolidated list of Cases from the Year 1967 till 1990 to be listed for hearing Pending CR. APP (DB) UpTo:- 1990 cases (as on 21/11/2019 ) Sl.No. Case No Party Name Current Status Status 1 507/1989 AWADH RAI VS. STATE AD BABULAL TIWARY and ORS VS. 2 8/1990 STATE Pending CR. APP (SJ) UpTo:- 1990 cases (as on 21/11/2019 ) Sl.No. Case No Party Name Current Status Status BISHWANATH RAI and ORS VS. 1 506/1981 AD STATE 2 569/1981 RAM CHANDRA SINGH VS. STATE ISHWARI LAL YADAV@ ISHWARI 3 530/1983 YAD VS. STATE 4 87/1984 SIARAM YADAV VS. STATE 5 531/1984 SHEOJI SINGH and ANR VS. STATE 6 688/1984 RAJENDRA PRASAD VS. STATE GIRISH CHANDRA GOSWAMI VS. 7 89/1990 THE STATE OF BIHAR Pending CR. MISC. UpTo:- 1990 cases (as on 21/11/2019 ) Sl.No. Case No Party Name Current Status Status DEO NANDAN SINGH and ORS VS. 1 4728/1986 AD STATE NAND KISHORE AGRWAL VS. STATE 2 9987/1987 OF BIHAR 3 12816/1987 SATYENDRA PRAKASH VS. SIYA RAM MANDAL AND ORS VS. 4 2165/1988 STATE 5 240/1989 MAHESH PD. SRIVASTAVA VS. ' KAILASH RAM VS. THE STATE OF 6 270/1989 BIHAR LAL PASWAN @ LALAN PASWAN and 7 283/1989 AR VS. THE STATE OF BIAHR 8 7282/1989 RAM DAYAL RAI and ORS VS. STATE 9 19316/1989 M/S DURGA BHANDAR VS. STATE 10 19439/1989 RAMA YADAV VS. 11 59258/1989 SITA RAM and ORS VS. STATE DHIRENDRA KR.SINGH VS. -

Year II-Chap.3-RAMAYANA

CHAPTER THREE Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman in RAMAYANA Year II Chapter 3-RAMAYANA THE RAMAYANA Introduction Valmiki is known as Adi Kabi, the first poet. He wrote an epic in Sanskrit, the Ramayana, which depicts the life of Rama, the hero of the story. Sage Narada narrated the story of Rama to Valmiki. Ramayana is divided into the following: o Balakanda (Book of Youth) - Boyhood of Rama, o Ayodhya Kanda (Book of Ayodhya) - Life in Ayodhya after Rama and Sita’s wedding, o Aranya Kanda (Book of Forest) – Rama’s forest life and abduction of Sita by Ravana, o Kishkindha Kanda (Book of Holy Monkey Empire) – Rama’s stay in Kishkindha after meeting Hanuman and Sugriva, o Sundara Kanda (Book of Beauty) – Hanuman’s Prank-locating Sita in Ashoka grove, and o Yuddha Kanda (Book of War) – Rama’s victory over Ravana in the war and Rama’s coronation. The period after coronation of Rama is considered in the last book - Uttara Kanda. The feature story Dasaratha was the king of Kosala, an ancient kingdom that was located in present day Uttar Pradesh. Ayodhya was its capital- located on the banks of the river Sarayu. Dasaratha was loved by one and all. His subjects were happy and his kingdom was prosperous. Even though Dasaratha had everything that he desired, he was very sad at heart; he had no children. During the same time, there lived a powerful Rakshasa (demon) king in the island of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), located just south of India. He was called Ravana. He had ten heads. -

8 Relevance of Ramayana to Modern Life

8 Relevance of Ramayana to modern life The whole universe is under the control of God. God is governed by Truth. Noble souls are the guardians of Truth. Such noble souls are verily The embodiments of Divinity. [Sanskrit sloka] Embodiments of Love! All are essentially the embodiments of Divinity. Eswara sarva bhoothanam (God dwells in all be- ings). Isavasyam idam jagat (God permeates the entire uni- verse). Where is the need to search for such an all-pervasive Divinity? Sarvata Pani Padam Tath Sarvathokshi Shiromu- kham, Sarvata Sruthimalloke Sarvamavruthya Thi- sthati. [Sanskrit sloka] How can you search for Him who is moving about with thousands of feet, thousands of eyes, and thousands of ears? It Sathya Sai Speaks, Volume 32 part1 99 is utterly foolish to search for God. God is within you. Since you have forgotten your true Self and are carried away by the temporary and transient physical body, you are unable to un- derstand the Divine. When you get rid of body attachment and develop attachment towards the Self, only then you can under- stand the divine Atmic Principle. Values contained in Rama's story Embodiments of Love! Life is like a game of chess; not merely that, it is like a battlefield. The story of Rama teaches us the threefold Dharma (code of conduct) pertaining to the individual, the family and the society. You have to make every effort to understand the duties of the individual, the family and the society. Rama is the ocean of compassion. He is love per- sonified. It is possible to understand His divinity only through the path of love. -

Bharata's Army Crosses the Ganges

“Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Ayodhya Kanda – Chapter 89 Bharata’s Army Crosses the Ganges Summary Having passed the night on the banks of Ganga, Bharata asks Guha to make arrangements for their troops to cross the river by boats. Accordingly, Guha has kept ready five hundred boat with their ferry-men for the purpose. All of them reach the opposite shore of the river. Encamping the army at the shore in the magnificent woods of Prayaga, Bharata along with the priests and king's counselors, approach the hermitage of Bharadwaja. Chapter [Sarga] 89 in Detail vyushya raatrim tu tatra eva gangaa kuule sa raaghavah | bharatah kaalyam utthaaya shatrughnam idam abraviit || 2-89-1 Bharata, born in Raghu race, having passed the night in that place on the banks of Ganga, rising at dawn, said to Shatrughna as follows: shatrugha uttishtha kim sheshe nishaada adhipatim guham | shiighram aanaya bhadram te taarayishyati vaahiniim || 2-89-2 "O, Shatrughna! wake up! Why sleep longer/ Bring Guha the king of Nishadas quickly and be happy. Let him convey the army across the river." jaagarmi na aham svapimi tathaiva aaryam vicintayan | ity evam abraviid bhraatraa shatrughno api pracoditah || 2-89-3 Thus urged by Bharata, his brother Shatrughna said, "I am not sleeping. Thinking of that Rama alone, I have been wakeful." Page 1 of 6 “Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Ayodhya Kanda – Chapter 89 iti samvadator evam anyonyam nara simhayoh | aagamya praanjalih kaale guho bharatam abraviit || 2-89-4 While those two lions -

RAMAYANA Retold by C

RAMAYANA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, American Gita Society) Contents 1. The Conception 39. A Second Father Dies 2. Sage Viswamitra 40. Left Eyelids Throb 3. Trisanku 41. He Sees Her Jewels 4. Rama Leaves Home 42. Sugriva's Doubts Cleared 5. Rama Slays The Monsters 43. The Slaying Of Vali 6. Sita 44. Tara's Grief 7. Bhagiratha And The Story Of 45. Anger And Reconciliation Ganga 46. The Search Begins 8. Ahalya 47. Son Of Vayu 9. Rama Wins Sita's Hand 48. The Search In Lanka 10. Parasurama's Discomfiture 49. Sita In The Asoka Park 11. Festive Preparations 50. Ravana's Solicitation 12. Manthara's Evil Counsel 51. First Among The Astute 13. Kaikeyi Succumbs 52. Sita Comforted 14. Wife Or Demon? 53. Sita And Hanuman 15. Behold A Wonder! 54. Inviting Battle 16. Storm And Calm 55. The Terrible Envoy 17. Sita's Resolve 56. Hanuman Bound 18. To The Forest 57. Lanka In Flames 19. Alone By Themselves 58. A Carnival 20. Chitrakuta 59. The Tidings Conveyed 21. A Mother's Grief 60. The Army Moves Forward 22. Idle Sport And Terrible Result 61. Anxiety In Lanka 23. Last Moments 62. Ravana Calls A Council Again 24. Bharata Arrives 63. Vibhishana 25. Intrigue wasted 64. The Vanara's Doubt 26. Bharata Suspected 65. Doctrine Of Surrender And Grace 27. The Brothers Meet 66. The Great Causeway 28. Bharata Becomes Rama's Deputy 67. The Battle Begins 29. Viradha's End 68. Sita's Joy 30. Ten Years Pass 69. Serpent Darts 31.