BR-October 08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Rajya Sabha Debates

5341 Oral Answers [24 SEP. 1965] to Questions 5342 RAJYA SABHA Friday, the 25th September, 1965/the 2nd Asvina, 1887 (Saka) The House met at ten of the clock, MR. CHAIRMAN in the Chair. ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS t[THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI JAISUKHLAL HATHI): A statement is laid on the Table of the House. STATEMENT A steady reduction in the proportion of those dependent on agriculture is an important objective of our Five Year Plan. In the Third Plan it was proposed that about two-thirds of the increase in the labour force during the 15 years 1961—1976 should be absorbed in non- f [AGRICULTURISTS AND AGRICULTURAL agricultural occupations. To this end LABOUR programmes for the development of industries, transport and power, rural •806. SHRI B. N. SHARGAVA: Will the industrialisation and intensification of Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to agriculture are being pursued systematically state what more steps Government propose to through our Plans. Special attention to these take to bring down the percentage of aspects is being given in the context of the agriculturists and agricultural labour in the Fourth Plan.] total number of working force?] ] English translation 748RS—1 5343 Oral Answers [ RAJYA SABHA] to Questions, 5344 SHRI M. M. DHARIA: Is the Government considering to have an enactment of the nature of minimum wages for agricultural labourers while bring, ing down the proportion? SHRI JAISUKHLAL HATHI: Perhaps that SHRI JAISUKHLAL HATHI: In the Third might be under the consideration of the Plan a target of employment opportunities for Labour Ministry. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

P. D. T. Achary LOKSABHASECRETAR~T NEW DELHI SPEAKER RULES SPEAKER RULES

P. D. T. Achary LOKSABHASECRETAR~T NEW DELHI SPEAKER RULES SPEAKER RULES P. D. T. ACHARY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi-I 10 001, (India). First Published, 2001 Price: Rs. 600/- ©2007 Lok Sabha Secretariat Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Eleventh Edition). Printed by: J ainco Art India, New Delhi-lIO 005, (India). TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Nos. FOREWORD ..................................................................................... (iii) PREFACE ••.........................................•..............................•••..........•• (v) CHAPTERS 1. Adjournment of Debate on a Bill ................................... 1 2. Adjournment Motion ..................................................... 5 3. Allegation ....................................................................... 20 4. Arrest of a Member ........................................................ 25 5. Bills ................................................................................ 30 6. Budget ............................... .......... ................................... 44 7. Calling Attention. ............. ........... ........... .......... ........... ... 59 8. Censure Motion against Ministers ......... ........................ 67 9. Consideration of Demands for Grants by Departmentally- related Standing Committees (DRSCs) ......................... 72 10. Custody of Papers of the House ..................................... 74 11. Cut Motions ........... ...... -

Olitical Amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of olitical amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA fc I A Guide to the Microfiche Collection POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Associate Editor and Guide compiled by August A. Imholtz, Jr. A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaîion Data: Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by a printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55655-206-8 (microfiche) 1. Political parties-India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1I527 1989<MicRR> 324.254~dc20 89-70560 CIP International Standard Book Number: 1-55655-206-8 UPA An Imprint of Congressional Information Service 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD20814 © 1989 by University Publications of America Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. TABLE ©F COMTEmn Introduction v Note from the Publisher ix Reference Bibliography Part 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups India Congress Committee. (Including All India Congress Committee): 1-282 ... 1 Communist Party of India: 283-465 17 Communist Party of India, (Marxist), and Other Communist Parties: 466-530 ... 27 Praja Socialist Party: 531-593 31 Other Socialist Parties: -

Bangladesh Enterprise Institute (Bei)

|| W E E K L Y N E W S H I G H L I G H T S || BANGLADESH ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE (BEI) A Brief Highlights on Contemporary Issues of South Asia Date: April 30, 2021 – May 06, 2021 MYANMAR: NATIONAL UNION GOVERNMENT & SRILANKA: SRILANKA MOVES TO BAN THE AFGHANISTAN: PULLOUT OF US and NATO UN SECURITY COUNCIL CONCERNS ON THE BURQA Forces FROM AFGHANISTAN: WARNING FROM ASEAN-JUNTA CONSENSUS THE TALIBAN The consensus made between ASEAN and the The Sri Lankan Cabinet has recently imposed a ban The Taliban has threatened US and NATO Junta leaders during last week to end the domestic on the burqa (outer veil worn by Muslim women) forces that it would resume targeting them in turmoil in Myanmar has earned mixed views from which is awaiting a debate at the legislature of the Afghanistan if they fail to withdraw all its various quarters, including the UN Security country. Public Security Minister, Sarath troops by 1 May 2021, as per the agreement Council. The National Union Government (NUG), Weerasekar, termed the burqa as a sign of religious signed in Qatar with the Taliban. According to the coalition of pro-democratic forces in extremism and a threat to national security. The the agreement, the US is supposed to Myanmar, was very skeptical about this proposal has been widely criticized as it is being completely withdraw all of its troops from development which, in their view, had impeded viewed as targeting and stigmatizing a minority Afghanistan within six weeks. However, the their voice to be heard. -

1463 Wakf (Amendment) [ 4 AUG

1463 Wakf (Amendment) [ 4 AUG. 1966 ] Bill, 1965 1464 tion. You have just announced that three should be added up and then deductions and a half hours have been allotted for the made only for the purpose of revenue, consideration of the Reports of the cess, rates and taxes payable to the Gov- Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and ernment or any local aumority, in order to Scheduled Tribes. Even in the past we arrive at the annual net income of the find that one full day was allotted always wakfs. Some matters have gone up to for consideration of such report. some of the High Courts, particularly to the Kerala High Court, where Ibis MR. CHAIRMAN : That is one day. definition has been challenged. It has been held by the Division Bench that the SHRI B. K. GAIKWAD : But we are net income as defined under section 3(g) considering two reports. Of course there of the Wakf Act means cash value of the will be so many speakers. Particularly produce of the land so direcdy cultivated when I want to express my view, I hope I less costs incurred on the related will be allowed. agricultural operations. The Bom. bay Public Trust Act, which governs parts of MR. CHAIRMAN : You will have Maharashtra and Gujarat of the former ample opportunity to express your view. Bombay State, as well as other State The House stands adjourned till 2.30 Wakf Acts, require calculation of P.M. contribution on the gross income, as the word 'gross' is commonly understood. The House then adjourned for lunch at five minutes past In another writ petition pending in the one of the clock. -

Forty Years: a Learning Curve FORTY YEARS: a LEARNING CURVE the FORD FOUNDATION PROGRAMS in INDIA 19524992 the Ford Foundation Programs in India 1952-1992

Forty Years: A Learning Curve FORTY YEARS: A LEARNING CURVE THE FORD FOUNDATION PROGRAMS IN INDIA 19524992 The Ford Foundation Programs in India 1952-1992 Forty Years: A learning Curve \ >£;,'•••: '••', ';! .\'At. "".••• . ' • . •• ' :.:u» , ••; •. • •" ^ -i ! '<•: . • ' ..; -. i.. •• • . • . ' vOV\ \ooo.ct 1 ®\X \l)(\\ Eugene S. Staples CONTENTS 40 Years: A Learning Curve The Ford Foundation in India, 1952-1992 Preface Chapter 1: India and the Ford Foundation: the Origins 1 Chapter 2: Food Production, Rural Poverty and Sustainable Agriculture 12 Chapter 3: Education and Culture, Rights and Governance 32 Chapter 4: Planning and Management 44 Chapter 5: Population, Child Survival and Reproductive Health 57 Chapter 6: The International Connections 67 Chapter 7: A Summing Up: An Outlook 72 Notes (1'rom right) Prime Minister Indira Candhi, l;ord Foundation Board Chairman J.A. Stratum, and Ford Foundation Representative Douglas Ensminger at 1970 dedication of Memorial Plaza for Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. PREFACE In February 1952 Dr. Douglas Ensminger, the first Representative of the Ford Foundation to be based in India, opened a small office in the Ambassador Hotel in New Delhi. This marked the beginning of a long association between the Foundation and the many individuals and institutions who have been responsible for India's development since Independence. To celebrate these four decades of association the Foundation commissioned Mr. Eugene S. Staples to write a brief history of the Foundation's work in India. We have given him a free hand to comment on and discuss our policies and programs, from his vantage as a former Representative of the Foundation in New Delhi from 1976 to 1981. -

West Bengal Election Results 2021

Cippicam Temple 01. Muttisvarar Temple 02. Putanatisvarar Temple 03. Suriyeswarar Temple 04. Arunachaleswarar Temple 05. Veerattaneswarar Temple WEST BENGAL ELECTIONS RESULTS LIST 2021 LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DOWNLOADED FROM INSTAPDF.IN Constituency Wining Trailing Name Winning Candidate Party Trailing Candidate Party Margin SOURAV CHAKRABORTY Alipurduars SUMAN KANJILAL BJP (GHUTIS) TMC 16007 Amdanga RAFIQUR RAHAMAN TMC JOYDEV MANNA BJP 25480 SUKANTA KUMAR DEBTANU Amta PAUL TMC BHATTACHARYA BJP 26205 Arambag MADHUSUDAN BAG BJP SUJATA MONDAL TMC 7172 Asansol Uttar Ghatak Moloy TMC Krishnendu Mukherjee BJP 21110 Ashoknagar NARAYAN GOSWAMI TMC TANUJA CHAKRABORTY BJP 23532 Asnsol Dakshin AGNIMITRA PAUL BJP SAYANI GHOSH TMC 4487 ABHEDANANDA Ausgram THANDER TMC KALITA MAJI BJP 11815 Baduria ABDUR RAHIM QUAZI TMC SUKALYAN BAIDYA BJP 56444 Bagda Biswajit Das BJP Paritosh Kumar Saha TMC 9792 Baghmundi Sushanta Mahato TMC Ashutosh Mahato AJSU Party 13969 Bagnan Arunava Sen (Raja) TMC Anupam Mallik BJP 30120 Subrata Maitra Baharampur (Kanchan) BJP Naru Gopal Mukherjee TMC 26852 SWADHIN KUMAR Baisnabnagar CHANDANA SARKAR TMC SARKAR BJP 2471 SUBHAS CHANDRA Balagarh MANORANJAN BAPARI TMC HALDAR BJP 5784 Balarampur BANESWAR MAHATO BJP SHANTIRAM MAHATO TMC 423 Bally RANA CHATTERJEE TMC BAISHALI DALMIYA BJP 6237 Ballygunge Subrata Mukherjee TMC LOKENATH CHATTERJEE BJP 75359 Balurghat Ashok Kumar Lahiri BJP Sekhar Dasgupta TMC 13436 Bandwan RAJIB LOCHAN SAREN TMC PARCY MURMU BJP 18831 Bangaon Dakshin SWAPAN MAJUMDER BJP ALO RANI SARKAR TMC 2004 Bangaon Uttar -

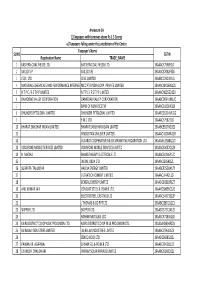

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT.