The Lost Girl Lawrence, David Herbert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Credits

Anne Dixon Costume Designer - Wardrobe Selected Credits: Costume Designer Anne, Season 1 Producer: Miranda de Pencier, Sue 2016-2017 Northwood Anne Inc. Murdoch, Moira Walley-Beckett Television Series Director: Various Production Manager: Teresa Ho Director of Photography: Bobby Shore Production Designer: Jean-Francois Campeau Costume Designer Our House Producer: Lee Kim, Marty Katz, Karen 2016 Our House Films Canada Inc. Wookey Feature Director: Anthony Scott Burns Production Manager: Sam Jephcott Director of Photography: Anthony Scott Burns Production Designer: Naz Goshtasbpour Costume Designer Shoot The Messenger, Producer: Jennifer Holness, Sudz 2015 Season 1 Sutherland, Victoria Woods Television Series Shoot the Messenger Director: Various Productions 1 Inc. Production Manager: Nancy Jackson Director of Photography: Arthur Cooper Production Designer: Rupert Lazarus Costume Designer Lavender Producer: Dave Valleau Lavender Films Inc. Director: Ed Gass-Donnelly Feature Production Manager: Aaron Barnett Director of Photography: Brendan Stacey Production Designer: Oleg Savitsky Costume Designer Born to Be Blue Producer: Jennifer Jonas, Leonard BTB Blue Productions Ltd. Farlinger, Robert Budreau Feature (NOHFC) Director: Robert Budreau Production Manager: Avi Federgreen Production Designer: Aidan Leroux Costume Designer Total Frat Movie Producer: Robert Wertheimer, Neil Digerati Films Inc. Bregman Feature Director: Warren Sonoda Production Manager: Kym Crepin Production Designer: Brian Verhoog Costume Designer Working the Engles, Season -

GSN Edition 01-01-13

Happy New Year The MIDWEEK Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2013 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 81, Number 01 8 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 weather report 21° 9 a.m. Saturday Today • Sunset, 4:34 p.m. Wednesday • Sunrise, 7:07 a.m. The dry conditions in 2012 contributed to numerous County Roads 20 and 54. The fire was one of several often hampered firefighting efforts. • Sunset, 4:35 p.m. fires, such as this one in a stubble field in June near believed to have been started by lightning. High winds Midday Conditions • Soil temperature 29 degrees • Humidity 54 percent • Sky sunny • Winds west 10 mph Drought, bricks are top stories • Barometer 30.23 inches and rising Was 2012 a year of great change? cember added to the total precipita- • Record High today 70° (1997) Or a year of the same-old same- tion. As of Dec. 28, Goodland had • Record Low today -15° (1928) old? A little bit of both as it turned seen 9.52 inches of precipitation out. The Goodland Star-News staff during 2012, making it not the dri- Last 24 Hours* has voted on the top 10 local news est year on record. The Blizzard on High Friday 27° stories of 2012. Stories 10 through Dec. 19 pushed Goodland over the Low Friday 1° six appeared in the Friday, Dec. 28, edge. 1956, which saw 9.19 inches, Precipitation none paper. The top five stories of the year remains the driest year. This month 0.50 appear below. -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

KATIE COUGHLIN C: 647.444.1420 E: [email protected]

KATIE COUGHLIN C: 647.444.1420 E: [email protected] 1st Assistant Production Ginny & Georgia Series Netflix Coordinator (Weekly) Producer: Claire Welland September – PM: James Crouch October 2019 PC: Adrian Sheepers 2nd Assistant Production Dare Me – Season 1 Series NBC Coordinator Producer: Dan Kaplow March – August PM: Victoria Woods 2019 PC: Redd Knight 1st Assistant Production What We Do in the Shadows - S1 Series FX Networks Coordinator Producer: Hartley Gorenstein October – PM: Stefan Steen December 2018 PC: Don Colafranceschi 2nd Assistant Production The Boys – Season 1 Series Sony Pictures / Amazon Coordinator Producer: Hartley Gorenstein April – October PM: Stefan Steen 2018 PC: Jonathan Pencharz 1st Assistant Production Polar Feature Constantin Film International Coordinator Producer: Hartley Gorenstein February – April PM: Anthony Pangalos 2018 PC: Jonathan Pencharz 2nd Assistant Production The Silence Feature Constantin Film International Coordinator Producer: Hartley Gorenstein September – PM: Stefan Steen December 2017 PC: Jonathan Pencharz 1st / 2nd Assistant Flatliners – Reshoot Feature Sony Pictures Production Coordinator Producer: Hartley Gorenstein June – August PM: Stefan Steen 2017 PC: Jonathan Pencharz 2nd Assistant Production Killjoys – Season 3 Series Syfy / Space Coordinator Producer: Lena Cordina December 2016 – Temple Street PM: Chris Shaw May 2017 PC: Jackie Alexander Moulson 1st APC: Meaghan Carey 2nd Assistant Production Man Seeking Woman – Season 3 Series FX Networks Coordinator Producer: Hartley -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 27 Dresses DVD-8204 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 28 Days Later DVD-4333 10th Victim DVD-5591 DVD-6187 12 DVD-1200 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 12 and Holding DVD-5110 3 Women DVD-4850 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 12 Monkeys DVD-3375 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 1776 DVD-0397 300 DVD-6064 1900 DVD-4443 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 1984 (Hurt) DVD-4640 39 Steps DVD-0337 DVD-6795 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 1984 (Obrien) DVD-6971 400 Blows DVD-0336 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 42 DVD-5254 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 50 First Dates DVD-4486 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 500 Years Later DVD-5438 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-0260 61 DVD-4523 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 70's DVD-0418 2012 DVD-4759 7th Voyage of Sinbad DVD-4166 2012 (Blu-Ray) DVD-7622 8 1/2 DVD-3832 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 8 Mile DVD-1639 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 9 to 5 DVD-2063 25th Hour DVD-2291 9.99 DVD-5662 9/1/2015 9th Company DVD-1383 Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet DVD-0831 A.I. -

(EFF) Passive Wi-Fi Monitoring Futu

Fri 8/29 10:00 A 11:30 A 1:00 P 2:30 P 4:00 P 5:30 P 7:00 P 8:30 P 10:00 P 11:30 P 201 (Hil) (EFF) Passive Wi-Fi Future of Fan Geocaching Remembering Revenge Porn TPB AFK In Defense of ISPs and Six Interracial Monitoring Fiction & and Location- Aaron Swartz and Online Strikes Discourse in Amateur Based Games Reputation- Pseudonyms Erotic Fiction Destroying Romance 202 (Hil) (SCI) The Genetics of Personalized Fun in Fusion The Human Neurogenetics: Of Your Lying Multiple- Cryonics: 2013 X-Men Genomics Research Body: A Mice and Men Eyes partner Updates/Open Walking Petri Families Disc. Dish w/Children 203 (Hil) (POD) Podcast Track How to Make comedy4cast Technorama Kick Off! Money with LIVE! Live! Your Podcast 204-207 (Hil) (SKEP) Skeptrack Kick Secrets of Why Mensa Don't Panic! It's Not News, Every Skeptic Has Skepticism Fictional Quiz-O-Tron Off 2013 Skeptic History Will Never Again... It's Fark a Story 101 Writing and 2000 Solve World Skepticism Hunger 309-310 (Hil) (SPACE) LiftPort Rises Life & Times at Don't Call Me XCor: Another You Won't Go There's an Curiosity, Year Reusable Bad Things Live from the Ashes JPL Dear, Call Me Vision of Crazy Asteroid With 1 Launch Happen to Astronomy (4 PhD.octor Commercial Earth's Name on It Vehicles Be a Good Galaxies Hrs) Space Reality? 311-312 (Hil) (WKS) RJ Haddy: Make-up Out of Kit Human Guinea Pigs (2.5 Hrs) Tai Chi Workshop Workshop (2.5 Hrs) A601-A602 (M) (MAIN) Bill Corbett, An Hour with Farscape: Same Getting The Work of Friday Night Costuming Contest 9:00 Lightspeed Dating (2.5 Hrs) Unlicensed Life Charlie Dren, Different Hatched! Michael Frith Pre-judging Setup/Light- Coach Schlatter Planet (2.5 Hrs) Speed Dating Reg. -

The Danish Girl

March-April 2016 VOL. 31 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES NO. 2 IN THIS ISSUE The Danish Girl | ALA Notables | The Brain | Spotlight on Fitness | Emptying the Skies | The Mama Sherpas | Chi-Raq | Top Spin scene & he d BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Le n more about Bak & Taylor’s Scene & He d team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified buyers ensure titles are available and delivered on time DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music shelf-ready specifications SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review The Danish Girl is taken aback. Married for six years, Einar enjoys a lusty conjugal life with Gerda—un- HHH1/2 til, one day, she asks him to don stockings, Universal, 120 min., R, DVD: $29.98, Blu-ray: tutu, and satin slippers to fill in for a miss- ing model. Sensing his delight in posing in Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.98, Mar. 1 Eddie Redmayne feminine finery, she suggests Einar attend a Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood followed up his Os- party, masquerading as a cousin named Lili. Copy Editor: Kathleen L. Florio car-winning turn as What neither of them expects is that demure Lili will attract amorous attention. -

Dan Carroll, Director, Media Relations 404 692 1958 Mediarelations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Dan Carroll, Director, Media Relations Phone: 404 692 1958 7/27/14 Email: [email protected] URL: www.dragoncon.org DRAGON CON CELEBRATES THE STARS OF TELEVISION AND MOVIES Actors from Star Trek, Star Wars, 2001 Space Odyssey and The Hobbit trilogy will be on hand, joined by the stars of Arrow, Game of Thrones, The Flash, Sleepy Hollow as well as True Blood and Warehouse 13. Sesame Street Meets Peachtree When Top Puppeteers Arrive ATLANTA – July 27, 2015 – Edward James Olmos, Nichelle Nichols, Peter Mayhew, Felicia Day, John Barrowman, David Ramsey, and Stephen Amell head an all-star guest list of more than 400 actors, authors, artists and other creators appearing at Dragon Con 2015, Atlanta’s internationally known pop culture, fantasy, sci-fi and gaming convention. Nichols, who broke barriers as Lt. Uhura in the original Star Trek television series, will serve as Grand Marshall of the annual Dragon Con Parade. Two doctors from the long-running BBC series Dr. Who – Sylvester McCoy and Paul McGann, the seventh and eight doctors, respectively – will appear together at this year’s Dragon Con. And, at this year’s Dragon Con, Sesame Street meets Peachtree. Famed puppeteer Carroll Spinney, who recently retired after 45 years performing Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch will appear along with the puppeteers behind other Sesame Street favorites including Abby Cadabby and Grundgetta. (While the puppeteers will be on hand, the characters will not.) Cheryl Henson, daughter of the late Jim Henson and president of the Jim Henson Foundation, will also join us for Dragon Con. -

Production Support Is Generously Provided by Larry & Sally Rayner Support for the 2015 Season of the Festival Theatre Is Ge

Production Sponsor Support for the 2015 season of Production support is the Festival Theatre is generously generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Bernstein Larry & Sally Rayner UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO Shakespeare lived in an age of rapid DISCOVERY: change, a time of new worlds, new beliefs and scientific discoveries. THAT EUREKA In short, he lived in an age very on the much like our own. But in that early modern age, change was MOMENT especially unsettling, overturning world stage societal foundations and leading to “We know what we revolution. In our own time we have This is a place where imagination are, but know not not only become inured to change, meets innovation — where we welcome it to the point where it is unconventional approaches push what we may be.” our new faith. performance to new heights and — Hamlet And so for the 2015 season I wanted allow talent to soar. to explore plays that especially Through research, teaching and examine discovery. In these plays, public engagement, University characters learn surprising truths of Waterloo is a proud supporter about the world around them or of culture and community. perhaps about themselves. In that eureka moment, their lives change forever. How do they deal with From Solitary to Solidarity: that change? At what cost comes Unravelling the Ligatures of Ashley Smith knowledge? Since Adam and Eve, March 2014 these questions have been at University of Waterloo Drama Faculty of Arts the centre of the human narrative. In 2015, through our playbill and in more than 200 Forum events, we will celebrate the power of the newest god in our pantheon – Discovery. -

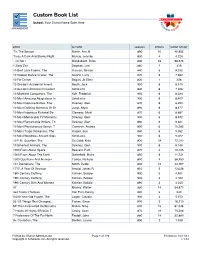

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Lost Girl Free

FREE LOST GIRL PDF Adam Nevill | 448 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447240914 | English | London, United Kingdom Lost Girl (TV Series –) - IMDb Kenzi and Bo's night out on the town leads to a series of potentially-deadly out of body experiences when an escaped Dark Fae madman poisons the beer kegs. Bo mounts a rescue mission to Lost Girl two people who are dear to her - unaware of the dangers facing those she thought were safe. Kenzi has an epiphany about Hale, and Dyson is given an important clue Chaos strikes when humans attack The Dal, leaving the fate Lost Girl one of the gang hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, The Morrigan exploits this opportunity to ignite the tensions between Light and Dark Looking for a movie Lost Girl entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. Lost Girl even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. Lost Girl Girl focuses on the gorgeous and charismatic Bo, a supernatural being called a succubus who feeds on the energy of humans, sometimes with fatal results. Refusing to embrace her supernatural clan system and its rigid hierarchy, Bo is a renegade who takes up the fight for the underdog while searching for Lost Girl truth about her own mysterious Lost Girl. Written by M. I've seen Lost Girl of sci-fi and fantasy, they are my favorite genres. Few of them do I enjoy enough to get the DVD and watch several times but this is one of those few. -

Showcase Announces Monster-Sized Slate of Guest Stars for Lost Girl’S Final Season

SHOWCASE ANNOUNCES MONSTER-SIZED SLATE OF GUEST STARS FOR LOST GIRL’S FINAL SEASON Lost Girl Season 5, Part 1 premieres December 7 at 9pm ET/PT For additional photography and press kit material visit: www.shawmedia.ca/media and follow us on Twitter at @shawmediaTV_PR FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TORONTO, November 28, 2014 – Ahead of Lost Girl’s epic return, Showcase announces fresh faces joining the Fae family and raising the stakes for the series’ dramatic final season. The previously unannounced guest stars joining the cast for a fond and ferocious #Faewell include Eric Roberts (The Dark Knight, The Expendables), Luke Bilyk (My Babysitter’s a Vampire, Degrassi: The Next Generation), Noam Jenkins (Covert Affairs, Rookie Blue, Longmire), Amanda Walsh (Two and a Half Men, NCIS, Grimm) and Shanice Banton (Degrassi: The Next Generation, A Day Late and a Dollar Short). The first eight episodes of Lost Girl’s fifth and final season begin Sunday, December 7 at 9pm ET/PT. Lost Girl follows supernatural seductress Bo (Anna Silk), the kickass, loveable succubus who feeds off sexual energy. Since realizing she is part of the Fae, creatures of legend and folklore who live among humans, Bo has forged her own path between the human and Fae worlds, while embarking on a mission to unlock the secrets of her origin. In season five, Bo’s determination to do the impossible for the people she loves triggers an explosive chain of events that will play out over the final episodes. Bo discovers that love is not always enough to keep a family together as she and her friends face an enemy unlike any they’ve faced before.