The Spell of Live Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2003 Issue (PDF)

N O T E S F R O M ZAMIR SPRING 2003 THE M AGAZINE OF THE Z AMIR C HORALE The Food of Italian Jews, page 27 OF B OSTON Zamir’s Mission to Israel, page 31 The Jews of Italy: A Paper Symposium MUSICA EBRAICA In 1622 the Venetian rabbi Leon Modena wrote, “No longer will arrogant opponents heap scorn on the Hebrew folk. They will see that it too pos- sesses talent, the equal of the best endowed.” What kind of scorn had Modena experienced? In 1611 Thomas Coryat published a book about his impressions of Venice. He referred to the sing- ing in the synagogue as “exceeding loud yelling, indecent roar- ing, and as it were a beastly bellowing.” What was the basis for Modena’s optimism? “There has arisen in Israel, thank God, a very talented man, versed in the singer’s skill, who has performed music before princes, yea, dukes and nobles. He set the words of the psalms to music or- ganized in harmony, designating them for joyous song before the Ark.” Salamone Rossi, That man was the Jewish composer Salamone Rossi, who, the Mystery Man of Jewish Art Music Composers in 1622, produced the first book of its kind: a stunning setting by Don Harrán 5 of the synagogue service. “He is more talented than any other Rabbis, Politics, and Music: man, not only those of our own people, for he has been com- Leon Modena and Salamone Rossi pared with, and considered the equal of, many of the famous by Howard Tzvi Adelman 8 men of yesterday among the families of the earth.” Lord & Tailor: As we listen to Rossi’s music we become aware of the ex- Fashioning Images of Jews in Renaissance Italy traordinary accomplishments of the Jews in Renaissance Italy. -

December 1984

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 8, NO. 12 Cover Photo by Layne Murdock CONTENTS FEATURES TERRY BOZZIO Although his work with such artists as Frank Zappa, the Brecker Brothers, and UK established Terry Bozzio's reputation as a fine drummer, his work with Missing Persons has revealed that there is more to Bozzio than was demonstrated in those other situations. Here, he talks about the hard work that went into starting his own band, explains his feelings that drummers should be more visible, and details his self-designed electronic drumset. by Rick Mattingly 8 OMAR HAKIM The fact that Weather Report and David Bowie have been sharing the same drummer says a lot about Omar Hakim's versatility, especially when one considers the wide range of styles that each of those situations encompasses. But Hakim's background prepared him well for the many diverse musical settings he has encountered, and he recounts that background in this amiable discussion of his life and career. by Robin Tolleson 14 INSIDE CALATO by Rick Van Horn 18 IAN PAICE The drummer for Deep Purple reminisces about the group's formation, discusses the band's reunion after an eight-year breakup, and describes Deep Purple's effect on today's music. He also talks about his experiences as the drummer for Whitesnake and Gary Moore, and explains the differences in playing with a guitar-oriented versus a vocal-oriented band. by Robyn Flans 22 TRISTAN FRY Modest Virtuoso by Simon Goodwin 26 DRIVER'S SEAT COLUMNS Phrasing With A Big Band PROFILES by Mark Hurley 112 PORTRAITS EDUCATION JAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOP Allen Herman New Concepts For Improved by Don Perman 30 THE MUSICAL DRUMMER Performance Chord Changes—Part 2 by Laura Metallo, Ph.D. -

Ecg1151 EJF2017 FINAL.Indd

14-23 July 2017 edinburghjazzfestival.com Welcome to our 2017 Festival. Blues from America For ten summer days Edinburgh will be Hamilton Loomis - p17 alive with uplifting music. years from the fi rst jazz recordings, we celebrate the Centenary of Jazz with a 100range of unique performances and special events. Jazz has been intertwined with blues since its origins and our blues programme, delves into the history of the music and showcases the musicians who are updating the tradition. Across both idioms and those around and in-between, this year’s programme off ers styles for all tastes – from bop to boogie to blues-rock; and from samba to swing to soul. International acts rub shoulders with homegrown talent and rising stars. Check out your favourites, of course, but we encourage you to get into the spirit of the Festival and try something new – you’re likely to discover a hidden gem! There are strong themes running through the programme: Jazz 100 marks the Centenary of jazz with a host of historic concerts Scottish Jazz Expo celebrates Scottish musicians take on that history, new Scottish bands and collaborations The Sound of New Orleans New Orleans comes to Edinburgh as we feature a host of musicians from the Soul Brass Band - p25 birthplace of jazz Cross The Tracks crosses the boundaries between jazz and contemporary urban music. And let yourself be transported by another Festival star – our venues! Dance under the magic mirrors of a grandiose cabaret tent located at the foot of Edinburgh Castle; enjoy the sumptuous surroundings and acoustics of Festival Theatre; get a great listening experience in the newly refurbished Rose Theatre, or drop in to the Traverse Café Bar - turned hip jazz joint. -

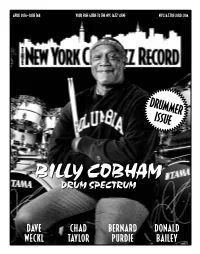

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Discographie

CHRISTIAN SCHOLZ UNTERSUCHUNGEN ZUR GESCHICHTE UND TYPOLOGIE DER LAUTPOESIE Teil III Discographie GERTRAUD SCHOLZ VERLAG OBERMICHELBACH (C) Copyright Gertraud Scholz Verlag, Obermichelbach 1989 ISBN 3-925599-04-5 (Gesamtwerk) 3-925599-01-0 (Teil I) 3-925599-02-9 (Teil II) 3-925599-03-7 (Teil III) [849] INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 389 [850] 1. ANTHOLOGIEN 389 [850] 2. VORFORMEN 395 [865] 3. AUTOREN 395 [866] II. SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR 439 [972] III. HÖRSPIELE 452 [1010] ANHANG 460 [1028] IV. VOKALKOMPOSITIONEN 460 [1029] V. NACHWORT 471 [1060] [850] I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 1. ANTHOLOGIEN Absolut CD # 1. New Music Canada. A salute to Canadian composers and performers from coast to coast. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD Absolut CD # 2. The Japanese Perspective. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Special Guest Editor: Toshie Kakinuma. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Yamatsuka Eye & John Zorn, Ushio Torikai u. a. CD Absolut CD # 3. Improvisation/Composition. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von David Moss, Joan La Barbara u. a. CD The Aerial. A Journal in Sound. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur Foundation 1990, Nr. 1, Winter 1990. AER 1990/1. Mit Beiträgen von David Moss, Malcolm Goldstein, Floating Concrete Octopus, Richard Kostelanetz u. a. CD The Aerial. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur 1990, Nr. 2, Spring 1990. AER 1990/2. Mit Beiträgen von Jin Hi Kim, Annea Lockwood, Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD The Aerial. -

The First West Coast Punk Band!

BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 199: COUNTER CULTURE 1 [Film Poster or Lobby Card]: Marihuana: Weed with Roots in Hell! [No place: no publisher 1936] Original poster. Approximately 14" x 22½". Printed in black, red, and yellow. Modest age-toning in the white portions, else just about fine. Crudely designed poster or lobby card for the 1936 exploitation filmMarihuana advertising itself as a “Daring Drug Expose” and promising “Weird Orgies, Wild Parties, Unleashed Passions” and illustrated with a comely lass being shot up by a marihuana pusher. An iconic image, reproduced many times for everything from giclée prints to coffee mugs, this is an original and authentic 1936 poster. [BTC#390506] BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 199: COUNTER CULTURE Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. Dimensions of items, including artwork, are given 112 Nicholson Rd. width first. All items are returnable within 10 days if returned in the same condition as Gloucester City, NJ 08030 sent. Orders may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. phone: (856) 456-8008 Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger fax: (856) 456-1260 purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, Visa, [email protected] Mastercard, American Express, Discover, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. betweenthecovers.com Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis for orders of $200 or more via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. -

FEBRUARY, 2009 Church of the Good Shepherd Lookout Mountain

THE DIAPASON FEBRUARY, 2009 Church of the Good Shepherd Lookout Mountain, Tennessee Chancel Organ Cover feature on pages 26–27 Feb 09 Cover 2-YES.indd 1 1/12/09 1:23:14 PM THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundredth Year: No. 2, Whole No. 1191 FEBRUARY, 2009 Henri Mulet as well. Besides the mere general fact Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 Byzantine speculations of the erection of the church, one of the An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, When I opened the December is- three chapels is dedicated to St. Peter. It the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music sue of The Diapason, I was thrilled to is interesting to note that, in this chapel, see an extended article on Henri Mulet. one of the marble plates of donors bears What a sensation! the name of the Parisian parish St-Roch Recently again in Paris, I took my where Mulet was organist. We found St. CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] family along the usual organist’s pil- Peter also present in the form of a statue 847/391-1045 grimage through the Parisian churches. placed in a niche in the back wall of the FEATURES In St-Sulpice we investigated the obe- sanctuary, receiving frequent adorations. University of Michigan lisk and enjoyed the posted reading The movement Procession may have also Historic Organ Tour 55 Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON material on the wall about the rumors a meaning beyond the common liturgi- by Jeffrey K. Chase 20 [email protected] caused by a recent novel. -

Vente De Vinyles

Vente de Vinyles LUNDI 20 JUIN 2016 À 14H30 JAZZ DES ANNÉES 1930 À 1970, DU 78 TOURS AU 33 TOURS COLLECTION DE M. L ET À DIVERS LOTS DE POP ROCK 60/70 9, RUE DES BOUCHERS - 03000 MOULINS EXPOSITIONS : JEU. 16 JUIN, 17H-20H, VEN. 17, 10H-13H, SAM. 18, 10H-12H30 ET 15H-17H30, DIM. 19, 15H-17H30, LUN. 20, 10H-13H CONSULTANT DISQUES VINYLES ERIC DESCHAMPS +33 (0)6 81 87 24 22 [email protected] INTÉGRALITÉ DES LOTS VISIblE SUR WWW.INTERENCHERES.FR/03003 WWW.GAZETTE-DROUOT.COM VENTES DIFFUSÉES EN LIVE SUR POUR TOUT RENSEIGNEMENT CONTACTER LE 04 70 44 05 28 OU [email protected] Expertises effectuées selon les critères du «goldmine grading system» norme internationale dédiée aux disques Vinyles. 1. POP / ROCK / PUNK / PROGRESSIVE / MUSIQUE CLASSIQUE lots 1 à 39 2. Disques 78t / 78rpm POP / WORLD / MANOUCHE-GISPY JAZZ/ MUSETTE / B.O.F… lots 40 à 57 3. HOT JAZZ / SWING / MIDDLE JAZZ & BOP lots 58 à 128 4. LIVRES DE JAZZ lots 129 à 131 5. JAZZ VOCAL lots 132 à 159 6. MUSIQUE ET CINEMA lots 160 à 169 7. COFFRET MILES DAVIS lot 170 8. JAZZ FRANÇAIS lots 171 à 176 9. LOTS DE BEBOP / HARD BOP / COOL / JAZZ ROCK lots 177 à 214 10. JAZZ “À LA PIÈCE” / BOP / HARD BOP / FREE / COOL / ACID JAZZ… lots 215 à 335 12 IGGY POP/TOM WAITS - LOT 2 LP: Pop / Rock / Punk / Progressive / Musique Classique IGGY POP, live 1977, TV EYE, USA 1978, disque VG+, pochette (cut) AC/DC Coffret 3 LP + 1 EP, VG+. -

Elenco Codici Lp Completo 29 01 15

1 LADNIER TOMMY Play That Thing L/US.2.LAD 2 WOODS PHIL Great Art Of Jazz L/US.2.WOO 3 PARKER CHARLIE Volume 3 L/US.2.PAR 4 ZEITLIN DENNY Live At The Trident L/US.2.ZET 5 COLTRANE JOHN Tanganyika Strut L/US.2.COL 6 MCPHEE JOE Underground Railroad L/US.2.MCP 7 ELLIS DON Shock Treatment L/US.2.ELL 8 MCPHEE/SNYDER Pieces Of Light L/US.2.MCP 9 ROACH MAX The Many Sides Of... L/US.2.ROA 10 MCPHEE JOE Trinity L/US.2.MCP 11 ELLINGTON DUKE The Intimate Ellington L/US.2.ELL 12 V.S.O.P V.S.O.P. L/US.2.VSO 13 MILLER/COXHILL Coxhill/Miller L/EU.2.MIL 14 PARKER CHARLIE The "Bird" Return L/US.2.PAR 15 LEE JEANNE Conspiracy L/US.2.LEE 16 MANGELSDORFF ALBERT Birds Of Underground L/EU.2.MAN 17 STITT SONNY Stitt's Bits Vol.1 L/US.2.STI 18 ABRAMS MUHAL RICHARD Things To Come From Those Now Gone L/US.2.ABR 19 MAUPIN BENNIE The Jewel In The Lotus L/US.2.MAU 20 BRAXTON ANTHONY Live At Moers Festival L/US.2.BRA 21 THORNTON CLIFFORD Communications Network L/US.2.THO 22 COLE NAT KING The Best Of Nat King Cole L/US.2.COL 23 POWELL BUD Swngin' With Bud Vol. 2 L/US.2.POW 24 LITTLE BOOKER Series 2000 L/US.2.LIT 25 BRAXTON ANTHONY This Time... L/US.2.BRA 26 DAMERON TODD Memorial Album L/US.2.DAM 27 MINGUS CHARLES Live With Eric Dolphy L/US.2.MIN 28 AMBROSETTI FRANCO Dire Vol. -

Art and Spirituality: the Ijumu Northeastern-Yoruba Egungun

Art and Spirituality: The Ijumu Northeastern-Yoruba Egungun Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Famule, Olawole Francis Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 16:10:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195753 ART AND SPIRITUALITY: THE IJUMU NORTHEASTERN -YORUBA EG ÚNG ÚN by Olawole Francis Famule Copyright Olawole Francis Famule 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committ ee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Olawole Francis Famule entitled Art and Spirituality: The Ijumu Northeastern -Yoruba Egungun and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History and Theory of Art ________________________________________________Date: 11/16/05 Paul E. Ivey ________________________________________________Date: 11/16/05 Aribidesi A. Usman ________________________________________________Date: 11/16/05 Julie V. Hansen ________________________________________________Date: 11/16/05 Keith McElroy Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

1 HENRY COWELL in the FLEISHER COLLECTION by GARY GALVÁN a DISSERTATION PRESENTED to the GRADUATE SCHOOL of the UNIVERSITY of F

HENRY COWELL IN THE FLEISHER COLLECTION By GARY GALVÁN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2007 1 © 2007 Gary Galván 2 To the memory of Edwin Adler Fleisher. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Kile Smith, Curator for the Edwin A. Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music. He carries on the noble ideas established by Edwin Fleisher and Arthur Cohn and inherently understands that “the best thing we can be about is access to these works … that’s the whole point in writing the music, so that it can be performed.” To that end, he has generously opened the seemingly boundless archives of the Fleisher Collection to me and proved an endless source of information on former Fleisher copyists and curators. His encyclopedic knowledge and ardent support have been instrumental in making this dissertation possible. Thanks go to my supervisory committee, David Z. Kushner, Jennifer Thomas, Welson Tremura, Raymond Chobaz, James Oliverio and Susan Read Baker, for their sage counsel and guidance for my project. My supervisory committee chair, the eminent Dr. Kushner, stands out as a persistent font of inspiration and a shining example of what a musicologist can and should be. Through his encouragement, I have had many fine opportunities to present my research in regional, national, and international venues. He is a real mensch. Richard Teitelbaum and Hiroko Sakurazawa of the David and Sylvia Teitelbaum Fund, Don McCormick, Curator for the Rodgers & Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound at the New York Public Library of Performing Arts, and Alyce Mott, Artistic Administrator at the Little Orchestra Society, granted the necessary permissions to acquire a recording of Cowell’s Symphony No. -

Bringing a Jazz Drumming Aesthetic to the Music of Diverse Cultures

Linking Improvisation to Cultural Context: Bringing a Jazz Drumming Aesthetic to the Music of Diverse Cultures Frank Gibson University of Otago An exegesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. This submission comprises a folio of creative work including three compact discs. 1 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and has not been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the exegesis itself. Frank Gibson June 2019 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 6 Prelude ............................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................. 11 1.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Research Design and Scope .............................................................................................. 12 1. 2.1 Conceptual Framework ..................................................................................................