ACCESS and THROUGHPUT in SOUTH AFRICAN HIGHER EDUCATION: THREE CASE STUDIES CHE Monitorprojectv9.Qxp 2010/03/30 11:38 AM Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corrective Rape and the War on Homosexuality: Patriarchy, African Culture and Ubuntu

Corrective rape and the war on homosexuality: Patriarchy, African culture and Ubuntu. Mutondi Muofhe Mulaudzi 12053369 LLM (Multidisciplinary Human Rights) Supervisor Prof Karin Van Marle Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Research Problem ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Research questions .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Motivation/Rationale .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Structure .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 2: Homophobic Rape – Stories and response by courts .......................................... 9 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 The definition -

2011 Annual Report

TWENTY Eleven DURBAN UNIVERSITY OF DUT TECHNOLOGY 2 DUT annual report 2011 Front Cover (from left to right) Professor Suren Singh - Head of Department Biotechnology and Food Technology Nokuthula Mchunu - Lecturer and Doctoral student in Biotechnology Professor Kugen Permaul - Professor in the Biotechnology and Food Technology Mchunu, under the co-supervision of Professor Permaul and Professor Maqsudal Alam, has completed ground-breaking research in the sequencing of an industrially important thermophillic fungal genome. 05 Message from the Chancellor 08 Report of the Chair of Council 14 Council Meetings and Attendance 18 Report of the Vice-Chancellor and Principal 25 Report on Internal Administrative/ Operational Structures and Controls 26 Council’s Report on Risk Exposure Assessment and the Management Thereof CONTENTS 28 Council’s Statement on Corporate Governance 34 Report of the Senate to Council 35 DVC: Academic Report 38 2011 Statistics 39 Composition of Senate 40 Financial Aid 41 Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT) 45 Centre for Quality Promotion and Assurance (CQPA) 49 Library Report 55 Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) 66 Report of the Institutional Forum to the Council 70 Faculty Reports 70 Accounting and Informatics 76 Applied Sciences 84 Arts and Design 94 Engineering and the Built Environment 104 Health Sciences 108 Management Sciences 118 Report of the Chief Financial Officer 124 Consolidated Annual Financial statements DUT annual report 2011 3 message from the chancellor DUT Chancellor Ela Gandhi, presents His Holiness Dalai Lama with a statue of Mahatma Gandhi 4 DUT annual report 2011 “there was an amazing resurgence of views on climate change; what we can do about it, and seeing young people going out there and getting things done.” Ela Gandhi – Chancellor I write this message with pride about an Institution with which I have Some amazing articles were produced by DUT students in a bid been associated for many years; initially in the 1960’s as a student to encourage recycling. -

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8 South Africa freedomhouse.org In May 2014, South Africa held national elections that were considered free and fair by domestic and international observers. However, there were growing concerns about a decline in prosecutorial independence, labor unrest, and political pressure on an otherwise robust media landscape. South Africa continued to be marked by high-profile corruption scandals, particularly surrounding allegations that had surfaced in 2013 that President Jacob Zuma had personally benefitted from state-funded renovations to his private homestead in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) won in the 2014 elections with a slightly smaller vote share than in 2009. The newly formed Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a populist splinter from the ANC Youth League, emerged as the third-largest party. The subsequent session of the National Assembly was more adversarial than previous iterations, including at least two instances when ANC leaders halted proceedings following EFF-led disruptions. Beginning in January, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) led a five-month strike in the platinum sector, South Africa’s longest and most costly strike. The strike saw some violence and destruction of property, though less than AMCU strikes in 2012 and 2013. The year also saw continued infighting between rival trade unions. The labor unrest exacerbated the flagging of the nation’s economy and the high unemployment rate, which stood at approximately 25 percent nationally and around 36 percent for youth. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 33 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 / 12 Elections for the 400-seat National Assembly (NA), the lower house of the bicameral Parliament, are determined by party-list proportional representation. -

South Africa February 2013

Blind Alleys PART II Country Findings: South Africa February 2013 The Unseen Struggles of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Urban Refugees in Mexico, Uganda and South Africa Acknowledgements This project was conceived and directed by Neil Grungras and was brought to completion by Cara Hughes and Kevin Lo. Editing, and project management were provided by Steven Heller, Kori Weinberger, Peter Stark, Eunice Lee, Ian Renner, and Max Niedzwiecki. In South Africa, we thank Liesl Theron of Gender DynamiX, Father Russell Pollitt and Dumisani Dube of Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh of Lawyers for Human Rights, and Braam Hanekom and Guillain KoKo of PASSOP (People Against Suffering, Oppression and Poverty) who gave us advice and essential access to its cli- ents. We thank Charmaine Hedding, Sibusiso Kheswa, Siobhan McGuirk, Tara Ngwato Polzer, Sanjula Weerasinghe, and Rachel Levitan for their work coordinating and conducting the field research. Expert feedback and editing was provided by Libby Johnston and Melanie Nathan. We are particularly grateful to Anahid Bazarjani, Nicholas Hersh, Lucie Leblond, Minjae Lee, Darren Miller, John Odle, Odessa Powers, Peter Stark, and Anna von Herrmann. These dedi- cated interns and volunteers conducted significant amounts of desk research and pored over thou- sands of pages of interview transcripts over the course of months, assuring that every word and every comment by interviewees were meticulously taken into account in this report. These pages would be blank but for the refugees who bravely recounted their sagas seeking pro- tection, as well as the dedicated UNHCR, NGO, and government staff who so earnestly shared their experiences and understandings of the refugees we all seek to protect. -

It's Torture Not Therapy

It’s Torture Not Therapy A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF CONVERSION THERAPY: PRACTICES, PERPETRATORS, AND THE ROLE OF STATES THEMATIC REPORT 20 irct.org 20 A Global Overview of Conversion Therapy TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Introduction This paper was written by Josina Bothe based on wide-ranging internet 5 Methodology research on the practices of conversion therapy worldwide. 6 Practices The images used belong to a series “Until You Change” produced by Paola 13 Perpetrators Paredes, which reconstructs the abuse of women in Ecuador’s conversion 15 State Involvement clinics, based on real life accounts. Paola, a photographer born in Quito, 19 Conclusions and Recommendations Ecuador, explores through her work issues facing the LGBT community and 20 Bibliography contemporary attitudes toward homo- sexuality in Ecuador. See: https://www.paolaparedes.com/ 2020 © International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Cover Photograph In front of the mirror, the ‘patient’ is observed by The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) another girl, who monitors the correct application is an independent, international health-based human rights organisation of the make-up. At 7.30am, she blots her lips with which promotes and supports the rehabilitation of torture victims, pro- femininity, daubs cheeks, until she is deemed a motes access to justice and works for the prevention of torture world- ‘proper woman’. wide. The vision of the IRCT is a world without torture. From “Until You Change” series by -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

'Ride-Hailing' Services, Uber Sonwabo C

AN INVESTIGATION INTO PASSENGERS’ EXPERIENCES OF A TRANSPORTATION NETWORK FIRM’S ‘RIDE-HAILING’ SERVICES, UBER SONWABO CIBI AND PHUMEZA NDZAMBO Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree BACCALAREUS COMMERCII HONORES in the FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC SCIENCES at the NELSON MANDELA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS MANAGEMENT Supervisor: Ms B Gray Date Submitted: October 2019 Place: Port Elizabeth DECLARATION We, Sonwabo Cibi and Phumeza Ndzambo, declare that: • The the entire body of work contained in this treatise, entitled “Passenger experiences of a transportation network firm’s ‘ride-hailing’ services”, is our original work and that no help was provided from other sources except for those allowed; • All sources used or quoted in sections of this treatise have been acknowledged and documented by means of complete references; and • This treatise has not previously been submitted by us or anyone else for a degree at any other tertiary institution. Mr Sonwabo Cibi Ms Phumeza Ndzambo Student number: 220660433 Student number: 219375925 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sonwabo Cibi First and foremost, I am grateful to the God for the good health and wellbeing that were necessary to complete this treatise. I would like to express my deep gratitude for the unwavering support, contribution and assistance from the following individuals during the course of this research project: • To my research supervisor, Ms Beverley Gray, for her patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work. • To my fellow researcher, Ms Phumeza Ndzambo, for her advice and assistance in keeping my progress on schedule. I also express my very great appreciation for her willingness to give her time, the stimulating discussions and for the sleepless nights we were working together before deadlines. -

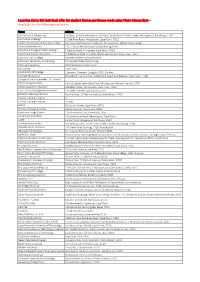

Learning Curve 8% Offer Campuses

Learning Curve 8% Cash Back offer for student licence purchases made using Virgin Money Spot - Available for the following campuses: Name Address AAA School of Advertising 1st Floor, Bond Street Centre, Cnr Bram Fischer Drive & Bond Street, Kensington B, Randburg, 2194 BHC School of Design 72 Salt River Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7925 Boston City Campus & Business College 247 Louis Botha Avenue, Orchards, Orange Grove, Johannesburg 2192 Boston Media House 137, 11th Street,Parkmore, Johannesburg 2196 Cape Town College of Fashion Design 7 Delaney Road, Plumstead, Cape Town, 7801 Cape Town Creative Academy The Old Biscuit Mill, 375 Albert Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7915 Capricorn TVET College Die Meer Street,Polokwane 0699 Centurion Akademie - Rustenberg 39 Heystek Street, Rustenburg Centurion Academy 1023 Bank Avenue Centurion City Varsity Cape Town Coastal KZN FET College 1 Jameson Crescent, Congella, 4013, Durban Concept Interactive COMMUNITYWest Block, Tannery ARTS CENTRE, Park, 23 LEONARD Belmont AUALA Road, Rondebosch,STREET, WINDHOEK, Cape Town, NAMIBIA 7700 College of The Arts (Reseller: PC Centre) CTU Training Solutions Unit 26, Garsfontein Office Park, 645 Jacqueline Drive, Pretoria, 1788 Design Academy of Fashion 208 Albert Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7925 East London Management Institute 231 Oxford Street, East London, 5201 Elizabeth Galloway Fashions Techno Road, 26 Techno Avenue, Stellenbosch, 7600 Faculty Training Institute CT Faculty Training Institute Joburg Fedisa 81 Church Street, Cape Town, 8001 Friends of Design Business -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY “2010 FIFA World Cup FNB TV Commercial.” Online video. 8 Feb. 2007. YouTube. 4 July 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjPazSFQrwA. “60’s Coke Commercial.” Online video. 13 Jan 2011. YouTube. 3 July 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQWoztEPbP4. A Normal Daughter: The Life and Times of Kewpie of District Six . Dir. Jack Lewis. 2000. “Abahlali Youth League Secretariat.” Abahlali baseMjondolo . Web. 1 Feb. 2012. http://abahlali.org/node/3710. “AbM Women’s League Launch—9 August 2008.” Abahlali baseMjondolo . Web. 1 Feb. 2012. http://abahlali.org/node/3893. Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 79, 22.1 (2004): 117-139. Web. 23 March 2011. ---. The Cultural Politics of Emotions . Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2004. Print. Alphen, Ernst van. “Affective operations in art and literature.” Res 53/54 (2008): 20-30. Web. Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Refl ections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism . London / New York: Verso, 2006. Print. Appadurai, Arjun. Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger . Durham / London: Duke UP, 2006. Print. Attridge, Derek. J.M. Coetzee and the Ethics of Reading . Chicago / London: U of Chicago P, 2004. Print. Attwel, David. “‘Dialogue’ and ‘Fulfi llment’ in J.M. Coetzee’s Age of Iron .” Writing South Africa. Literature, Apartheid, and Democracy, 1970-1995 . Eds. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 221 H. Stuit, Ubuntu Strategies, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58009-2 222 BIBLIOGRAPHY Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998: 166- 179. Print. Baderoon, Gabeda. “On Looking and Not Looking.” Mail & Guardian . -

The Expenditure and Foreign Revenue Impact of International Students on the South African Economy

THE EXPENDITURE AND FOREIGN REVENUE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ON THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY Naum Aloyo* University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] Arnold Wentzel# University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] July 2011 Abstract In South Africa, there is still no clear policy of internationalisation of higher education, partly due to limited research. So far, only two efforts – at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) in 2004 and Rhodes University in 2005 – have been made to determine the expenditure and foreign revenue impact of international students on South Africa. Each of these papers sampled only a single university, so they are of limited use for national impact analysis. To build on these studies, this research was conducted at six South African universities that admit the largest number of international students and also included the economic effects of spending items hitherto neglected. We show that international students (mainly from Africa) contribute significantly to South African GDP and balance of payments, but that South Africa still lags behind in exploiting and enhancing these benefits. Keywords Export of education, international students, economic impact _________________________________ * Mr Naum Aloyo is a doctoral student in Economics at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. # Mr Arnold Wentzel is a senior lecturer in Economics at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences | JEF | October 2011 4(2), pp. 391-406 391 EXPENDITURE AND FOREIGN REVENUE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ON THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY 1. INTRODUCTION Internationalisation of university education has advanced over the past decade and has gained momentum as a result of globalisation. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS OVERVIEW ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE Letter to the Minister for Training and Skills Introduction and scope 51 and Minster for Higher Education 3 • Commitments, governance and resources 51 Vice-Chancellor’s statement 4 • Staff resources 52 Report of members of Monash University Council 6 • Staff and student engagement 53 • Establishment, objectives, and principal activities 6 • Biodiversity 54 • Members of Council 6 • Carbon management 55 • Membership of Audit and Risk Committee 7 • Energy consumption 56 • Subcommittees of Council 8 • Water consumption 58 • Meetings of members 8 • Waste 59 Senior officers 9 • Sustainable transport 60 • Deputy Chancellors 9 • Procurement 60 • Insurance of officers 9 • The built environment and landscape 61 • Organisational charts 11 • Statements of compliance 62 • Organisational charts 12 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE CORE BUSINESS: EDUCATION, Report on financial operations 65 RESEARCH, GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT • Major financial and performance statistics 66 Operational objectives and initiatives 14 • Statement of consolidated financial position 66 • Key initiatives and projects 14 • Statement of consolidated cashflows 66 Research and Education: Office of the Provost • Statement of consolidated financial performance 67 and Senior Vice-President 16 • Risk Analysis – subsidiaries 68 • Research – Excellence 16 • Statement on risk management 68 • Enterprising 18 • Consultants 69 • Education 20 • Statement on compulsory non-academic fees 69 • Global Engagement 22 • Statement on private provision of -

Abstract Booklet

15th Biennial Conference South African Association of Political Studies ABSTRACT BOOKLET Theme: Rethinking Politics Dates: Host: Department of in a Time of Crisis 26-28 Political and International Venue: Virtual (Zoom) August 2021 Studies, Rhodes University For more information: ru.ac.za saaps2021 @saapsconferenc1 [email protected] saaps.org.za saaps 2021 conference saaps 2021 conference Dear conference presenters and attendees, Please find below the biographies of our three keynote speakers. This is followed by the biographies and abstracts of all presenters in alphabetical order according to the surname of the presenter. Best wishes, The SAAPS 2021 Local Organising Committee Plenary 1 South Africa: Present Tense, Future Imperfect By Judith February Judith February is a lawyer, governance specialist and columnist. She is currently a Visiting Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance. Prior to that she was executive director of the Human Sciences Research Council’s Democracy and Governance unit and also head of the Idasa’s South African Governance programme for 9 years. Judith has worked extensively on issues of good governance, institutional strengthening and transparency and accountability within the South African context. Her areas of focus include corruption and its impact on governance, Parliamentary oversight and institutional design. Judith is also a regular commentator in the media on politics in South Africa and a columnist for the Daily Maverick and other publications. Judith is the author of Turning and turning: exploring the complexities of South Africa's democracy (PanMacmillan, 2018). Plenary 2 Reading crisis through the social: Some dilemmas for South African politics By Shireen Hassim Professor Shireen Hassim is a Canada 150 Research Chair in Gender and African Politics at Carleton University in Canada.