'Ride-Hailing' Services, Uber Sonwabo C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report

TWENTY Eleven DURBAN UNIVERSITY OF DUT TECHNOLOGY 2 DUT annual report 2011 Front Cover (from left to right) Professor Suren Singh - Head of Department Biotechnology and Food Technology Nokuthula Mchunu - Lecturer and Doctoral student in Biotechnology Professor Kugen Permaul - Professor in the Biotechnology and Food Technology Mchunu, under the co-supervision of Professor Permaul and Professor Maqsudal Alam, has completed ground-breaking research in the sequencing of an industrially important thermophillic fungal genome. 05 Message from the Chancellor 08 Report of the Chair of Council 14 Council Meetings and Attendance 18 Report of the Vice-Chancellor and Principal 25 Report on Internal Administrative/ Operational Structures and Controls 26 Council’s Report on Risk Exposure Assessment and the Management Thereof CONTENTS 28 Council’s Statement on Corporate Governance 34 Report of the Senate to Council 35 DVC: Academic Report 38 2011 Statistics 39 Composition of Senate 40 Financial Aid 41 Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT) 45 Centre for Quality Promotion and Assurance (CQPA) 49 Library Report 55 Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) 66 Report of the Institutional Forum to the Council 70 Faculty Reports 70 Accounting and Informatics 76 Applied Sciences 84 Arts and Design 94 Engineering and the Built Environment 104 Health Sciences 108 Management Sciences 118 Report of the Chief Financial Officer 124 Consolidated Annual Financial statements DUT annual report 2011 3 message from the chancellor DUT Chancellor Ela Gandhi, presents His Holiness Dalai Lama with a statue of Mahatma Gandhi 4 DUT annual report 2011 “there was an amazing resurgence of views on climate change; what we can do about it, and seeing young people going out there and getting things done.” Ela Gandhi – Chancellor I write this message with pride about an Institution with which I have Some amazing articles were produced by DUT students in a bid been associated for many years; initially in the 1960’s as a student to encourage recycling. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

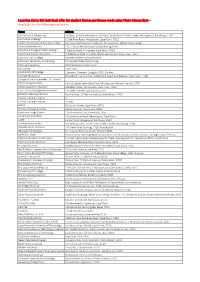

Learning Curve 8% Offer Campuses

Learning Curve 8% Cash Back offer for student licence purchases made using Virgin Money Spot - Available for the following campuses: Name Address AAA School of Advertising 1st Floor, Bond Street Centre, Cnr Bram Fischer Drive & Bond Street, Kensington B, Randburg, 2194 BHC School of Design 72 Salt River Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7925 Boston City Campus & Business College 247 Louis Botha Avenue, Orchards, Orange Grove, Johannesburg 2192 Boston Media House 137, 11th Street,Parkmore, Johannesburg 2196 Cape Town College of Fashion Design 7 Delaney Road, Plumstead, Cape Town, 7801 Cape Town Creative Academy The Old Biscuit Mill, 375 Albert Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7915 Capricorn TVET College Die Meer Street,Polokwane 0699 Centurion Akademie - Rustenberg 39 Heystek Street, Rustenburg Centurion Academy 1023 Bank Avenue Centurion City Varsity Cape Town Coastal KZN FET College 1 Jameson Crescent, Congella, 4013, Durban Concept Interactive COMMUNITYWest Block, Tannery ARTS CENTRE, Park, 23 LEONARD Belmont AUALA Road, Rondebosch,STREET, WINDHOEK, Cape Town, NAMIBIA 7700 College of The Arts (Reseller: PC Centre) CTU Training Solutions Unit 26, Garsfontein Office Park, 645 Jacqueline Drive, Pretoria, 1788 Design Academy of Fashion 208 Albert Road, Woodstock, Cape Town, 7925 East London Management Institute 231 Oxford Street, East London, 5201 Elizabeth Galloway Fashions Techno Road, 26 Techno Avenue, Stellenbosch, 7600 Faculty Training Institute CT Faculty Training Institute Joburg Fedisa 81 Church Street, Cape Town, 8001 Friends of Design Business -

The Expenditure and Foreign Revenue Impact of International Students on the South African Economy

THE EXPENDITURE AND FOREIGN REVENUE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ON THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY Naum Aloyo* University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] Arnold Wentzel# University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] July 2011 Abstract In South Africa, there is still no clear policy of internationalisation of higher education, partly due to limited research. So far, only two efforts – at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) in 2004 and Rhodes University in 2005 – have been made to determine the expenditure and foreign revenue impact of international students on South Africa. Each of these papers sampled only a single university, so they are of limited use for national impact analysis. To build on these studies, this research was conducted at six South African universities that admit the largest number of international students and also included the economic effects of spending items hitherto neglected. We show that international students (mainly from Africa) contribute significantly to South African GDP and balance of payments, but that South Africa still lags behind in exploiting and enhancing these benefits. Keywords Export of education, international students, economic impact _________________________________ * Mr Naum Aloyo is a doctoral student in Economics at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. # Mr Arnold Wentzel is a senior lecturer in Economics at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences | JEF | October 2011 4(2), pp. 391-406 391 EXPENDITURE AND FOREIGN REVENUE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS ON THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY 1. INTRODUCTION Internationalisation of university education has advanced over the past decade and has gained momentum as a result of globalisation. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS OVERVIEW ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE Letter to the Minister for Training and Skills Introduction and scope 51 and Minster for Higher Education 3 • Commitments, governance and resources 51 Vice-Chancellor’s statement 4 • Staff resources 52 Report of members of Monash University Council 6 • Staff and student engagement 53 • Establishment, objectives, and principal activities 6 • Biodiversity 54 • Members of Council 6 • Carbon management 55 • Membership of Audit and Risk Committee 7 • Energy consumption 56 • Subcommittees of Council 8 • Water consumption 58 • Meetings of members 8 • Waste 59 Senior officers 9 • Sustainable transport 60 • Deputy Chancellors 9 • Procurement 60 • Insurance of officers 9 • The built environment and landscape 61 • Organisational charts 11 • Statements of compliance 62 • Organisational charts 12 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE CORE BUSINESS: EDUCATION, Report on financial operations 65 RESEARCH, GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT • Major financial and performance statistics 66 Operational objectives and initiatives 14 • Statement of consolidated financial position 66 • Key initiatives and projects 14 • Statement of consolidated cashflows 66 Research and Education: Office of the Provost • Statement of consolidated financial performance 67 and Senior Vice-President 16 • Risk Analysis – subsidiaries 68 • Research – Excellence 16 • Statement on risk management 68 • Enterprising 18 • Consultants 69 • Education 20 • Statement on compulsory non-academic fees 69 • Global Engagement 22 • Statement on private provision of -

Abstract Booklet

15th Biennial Conference South African Association of Political Studies ABSTRACT BOOKLET Theme: Rethinking Politics Dates: Host: Department of in a Time of Crisis 26-28 Political and International Venue: Virtual (Zoom) August 2021 Studies, Rhodes University For more information: ru.ac.za saaps2021 @saapsconferenc1 [email protected] saaps.org.za saaps 2021 conference saaps 2021 conference Dear conference presenters and attendees, Please find below the biographies of our three keynote speakers. This is followed by the biographies and abstracts of all presenters in alphabetical order according to the surname of the presenter. Best wishes, The SAAPS 2021 Local Organising Committee Plenary 1 South Africa: Present Tense, Future Imperfect By Judith February Judith February is a lawyer, governance specialist and columnist. She is currently a Visiting Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance. Prior to that she was executive director of the Human Sciences Research Council’s Democracy and Governance unit and also head of the Idasa’s South African Governance programme for 9 years. Judith has worked extensively on issues of good governance, institutional strengthening and transparency and accountability within the South African context. Her areas of focus include corruption and its impact on governance, Parliamentary oversight and institutional design. Judith is also a regular commentator in the media on politics in South Africa and a columnist for the Daily Maverick and other publications. Judith is the author of Turning and turning: exploring the complexities of South Africa's democracy (PanMacmillan, 2018). Plenary 2 Reading crisis through the social: Some dilemmas for South African politics By Shireen Hassim Professor Shireen Hassim is a Canada 150 Research Chair in Gender and African Politics at Carleton University in Canada. -

Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 13 DECEMBER 2016 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

ACCESS and THROUGHPUT in SOUTH AFRICAN HIGHER EDUCATION: THREE CASE STUDIES CHE Monitorprojectv9.Qxp 2010/03/30 11:38 AM Page 2

6540HE_MoniReport9:Monitor 9 4/6/10 8:27 AM Page 1 Council on Higher Education Published by: Council on Higher Education 1 Quintin Brand Street Persequor Technopark Brummeria Higher Education Monitor Pretoria South Africa PO Box 94 Access and throughput in South African Persequorpark 0020 Higher Education: Three case studies South Africa Tel: +27 12 349 3936 Fax: +27 12 349 3928 Website: http://www.che.ac.za Higher Education Monitor. Access and throughput in South African Higher Education: Three case studies Higher Education Monitor. ISBN 978-1-919856-75-9 Date of Publication: March 2010 Material from this publication may not be reproduced without the CHE’s permission. ©Council on Higher Education Pretoria HE Monitor No. 9 Designed by Blue Apple Publishing March 2010 CHE_MonitorProjectV9.qxp 2010/03/30 11:38 AM Page 1 Council on Higher Education ACCESS AND THROUGHPUT IN SOUTH AFRICAN HIGHER EDUCATION: THREE CASE STUDIES CHE_MonitorProjectV9.qxp 2010/03/30 11:38 AM Page 2 ACCESS AND THROUGHPUT IN SOUTH AFRICAN HIGHER EDUCATION: THREE CASE STUDIES The South African Council on Higher Education (CHE) is an independent statutory body responsible for advising the Minister of Higher Education and Training on all higher education policy issues, and for quality assurance in higher education and training. 1 Quintin Brand Street Persequor Technopark Brummeria Pretoria South Africa P O Box 94 Persequorpark 0020 South Africa Tel: +27 12 349 3936 Fax: +27 12 349 3928 Website: http://www.che.ac.za ISBN 978-1-919856-75-9 Date of Publication: March 2010 Material from this publication may not be reproduced without the CHE's permission. -

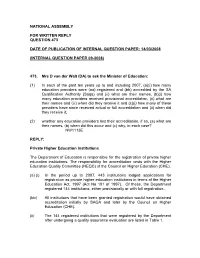

14/03/2008 (Internal Question P

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WRITTEN REPLY QUESTION 473 DATE OF PUBLICATION OF INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: 14/03/2008 (INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER 09-2008) 473. Mrs D van der Walt (DA) to ask the Minister of Education: (1) In each of the past ten years up to and including 2007, (a)(i) how many education providers were (aa) registered and (bb) accredited by the SA Qualification Authority (Saqa) and (ii) what are their names, (b)(i) how many education providers received provisional accreditation, (ii) what are their names and (iii) when did they receive it and (c)(i) how many of these providers have since received actual or full accreditation and (ii) when did they receive it; (2) whether any education providers lost their accreditation, if so, (a) what are their names, (b) when did this occur and (c) why, in each case? NW1113E REPLY: Private Higher Education Institutions The Department of Education is responsible for the registration of private higher education institutions. The responsibility for accreditation vests with the Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC) of the Council on Higher Education (CHE). (a) (i) In the period up to 2007, 443 institutions lodged applications for registration as private higher education institutions in terms of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No 101 of 1997). Of these, the Department registered 144 institutions, either provisionally or with full registration.. (bb) All institutions that have been granted registration would have obtained accreditation initially by SAQA and later by the Council on Higher Education (CHE). (ii) The 144 registered institutions that were registered by the Department after undergoing a quality assurance evaluation are listed in Table 1. -

Register of Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 22 MAY 2019 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers ‐2 ‐ INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

Political Animal Newsletter of the Department of Politics and International Relations Issue 2, 2019 Editorial Renewed Hope In

Political Animal Newsletter of the Department of Politics and International Relations Issue 2, 2019 Editorial Renewed hope in the era of increased democratic fragility South Africa’s progression over the past 25 years of democratic rule has implored us to reflect, applaud strides made, heed persistent challenges, and self- introspect on our role as a citizenry of a liberal democratic regime. While much headway has been made to engender increased political participation, respect for diversity, fostering of gender equality, and the equitable distribution of public goods, there are still glaring challenges that perceivably debase our democracy The Editorial Board into a state of fragility and vulnerability. The lack of political accountability, Sven Boths (Lead Editor) increased socio-economic inequalities and the scourge of gender based Tshepo Morabe violence, coupled with the triple burden of poverty, unemployment and pervasive (Assistant Lead Editor) government looting and corruption, are but a few gloomy confrontations that Sekgololo Johannes have undoubtedly set us into a state of national anxiety. (Student Affairs Editors) C. Caroline Williams Sfiso Sabela In spite of this seemingly trepidatious state of affairs, hope for a better future is (Publications Editor) what keeps us alive and buoyant. Hope affords us the opportunity to imagine and Paseka Mmako Thando Moyana strive towards betterment in the face of much anxiety and banality. This issue of (Publications Editor) the Political Animal bears testament to some of the initiatives, academic Prof Suzanne Graham Dr Fritz Nganje engagements, and ideas by thought leaders that inspire and stimulate hopeful (Academic Advisors) prospects for strengthening political participation, co-operation, collaboration and active global citizenry. -

The 5Th International Symposium on Service-Learning (ISSL) to Stellenbosch, in the Heart of the Boland Region of the Western Cape, South Africa

5th INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM SERVICE-LEARNING Service-Learning across the globe: from local to transnational PROCEEDINGS 20-22 NOVEMBER 2013 Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa Proceedings Organised and hosted by: Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa & University of Indianapolis, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA Co-Sponsored by: South African Higher Education Community Engagement Forum, South Africa Talloires Network, United States of America Antoinette Smith Tolken (Editor) 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the Planning Committee, The Fifth International Symposium on Service-Learning, Stellenbosch University (SU) of University of Indianapolis (UIndy) ISBN: 978-0-620-59083-9 All rights reserved. No portion of this monograph may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission of the Planning Committee, International Symposium on Service-Learning 2013. Planning: Symposium Chair: Dr Antoinette Smith-Tolken, Stellenbosch University Symposium Co-Chair: Dr Phylis Lan Lin, University of Indianapolis Proceedings editing and proofreading contributions: Dr Antoinette Smith-Tolken and Joanne Williams Cover Source: Chinese Ink Brush Painting by Bonnie Kwan Huo; Stellenbosch University Ou Hoofgebou and University of Indianapolis Goodhall Building. Cover Design and Layout: SUN MeDIA Stellenbosch Student Assistant: Mariska de Winnaar Major funding support to make this publication possible: Prof Julian Smith: Vice Rector, Community Interaction and Personnel, Stellenbosch University. Prepared by: Dr Antoinette Smith-Tolken