A Case Study of Cloughjordan Eco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethical Consumerism November 2015

UK Data Archive Study Number 7787 - Twenty-First Century Evangelicals Ethical Consumerism November 2015 Welcome Thank you for taking part in the 21st Century Evangelicals online research. These surveys are designed by the Evangelical Alliance. The findings will appear in IDEA magazine and on our website. This quarter's survey is about the decisions we all make as consumers. For example, spotting a good bargain, choosing fairtrade products, avoiding environmentally damaging practices and investing money in businesses without asking too many questions about how it might be used. All answers are anonymous. If you'd really rather not answer a particular question you can always leave it blank. People vary, but we estimate the survey shouldn’t take longer than about 20 minutes, unless you choose to write a lot in openended comment boxes. Page 1 Ethical Consumerism November 2015 About you In every survey we need to ask everyone a few short background questions so that we can easily break down the responses from different groups of people. We apologise if you have completed this for a previous survey – unfortunately we cannot carry over your demographic data. 1. Your gender: (' Male (' Female 2. In which decade were you born? (' 1920s (' 1960s (' 1930s (' 1970s (' 1940s (' 1980s (' 1950s (' 1990s Page 2 Ethical Consumerism November 2015 Are you a Christian? 3. Do you consider yourself to be a committed Christian (i.e. someone who believes in God, tries to follow Jesus, practises your faith, prays and attends church as you are able)? (' Yes (' No (' Unsure 4. Do you consider yourself to be an evangelical Christian? (' Yes (' No (' Unsure Page 3 Ethical Consumerism November 2015 Where do you live? 5. -

Segmenting Consumers' Reasons for and Against Ethical Consumption

Segmenting Consumers’ Reasons For and Against Ethical Consumption Citation: Burke, P.F., Eckert, C., & Davis, S. (2014). Segmenting consumers’ reasons for and against ethical consumption. European Journal of Marketing, 48(11/12), 2237-2261. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2013-0294 Author Affiliations: University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Australia Corresponding author: Dr Paul F. Burke via email [email protected] 1 Segmenting Consumers’ Reasons For and Against Ethical Consumption Purpose: This paper quantifies the relative importance of reasons used to explain consumers’ selection and rejection of ethical products, accounting for differences in ethical orientations across consumers. Approach: Reviewing previous literature and drawing on in-depth interviews, a taxonomy of reasons for and against ethical purchasing is developed. An online survey incorporating best-worst scaling determines which reasons feature more in shaping ethical consumerism. Cluster analysis and multinomial regression are used to identify and profile segments. Findings: Positively orientated consumers (42% of respondents) purchase ethical products more so because of reasons relating to impact, health, personal relevance, and quality. Negatively orientated consumers (34% of respondents) reject ethical alternatives based on reasons relating to indifference, expense, confusion, and scepticism. A third segment is ambivalent in their behaviour and reasoning; they perceive ethical purchasing to be effective and relevant, but are confused and sceptical under what conditions this can occur. Limitations: Preferences were elicited using an online survey rather than using real market data. Though the task instructions and methods used attempted to minimise social-desirability bias, the experiment might still be subject to its effects. Implications: Competitive positioning strategies can be better designed knowing which barriers to ethical purchasing are more relevant. -

Ethical Consumption As a Reflection of Self-Identity

Ethical consumption as a reflection of self-identity Hanna Rahikainen Department of Marketing Hanken School of Economics Helsinki 2015 HANKEN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Department of Marketing Type of work: Master’s Thesis Author: Hanna Rahikainen Date: 31.7.2015 Title of thesis: Ethical consumption as a reflection of self-identity Abstract: In recent years, people’s increasing awareness of ethical consumption has become increasingly important for the business environment. Although previous research has shown that consumers are influenced by their ethical concerns, ethical consumption from a consumer perspective lacks understanding. As self-identity is an important concept in explaining how consumers relate to different consumption objects, relating it to ethical consumption is a valuable addition to the existing body of research. As the phenomenon of ethical consumption has been widely studied, but the literature is fragmented covering a wide range of topics such as sustainability and environmental concerns, the theoretical framework of the paper portrays the multifaceted and complex nature of the concepts of ethical consumption and self-identity and the complexities existing in the relationship of consumption and self-identity in general. The present study took a qualitative approach to find out how consumers define what ethical consumption is to them in their own consumption and how self-identity was related to ethical consumption. The informants consisted of eight females between the ages of 25 – 29 living in the capital area of Finland. The results of the study showed an even greater complexity connecting to ethical consumption when researched from a consumer perspective, but indicated clearly the presence of a plurality of identities connected to ethical consumption, portraying it as one of the behavioural modes selected or rejected by an active self. -

The Ethics of Environmentalism for the Individual Consumer Molly Collins

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2016 The ethics of environmentalism for the individual consumer Molly Collins Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Molly, "The thice s of environmentalism for the individual consumer" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 970. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ethics ofEnvironmentalism for the Individual Consumer Molly Collins Honors Thesis Submitted to The Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, VA April 29, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Jessica Flanigan Abstract The Ethics ofEnvironmentalism for the Individual Consumer Molly Collins Committee Members: Dr. Jessica Flanigan, Dr. Terry Price, Dr. Eugene Wu, Dr. Robert Andrejewski Climate change harms the well-being of humans. It is the poor choices of individual consumers that contribute to climate change. I argue that it is immoral to cause harm to others, thus climate change is an ethical dilemma for individual consumers. I begin with a pluralistic discussion of harm, before discussing the duties of individuals to make choices that will mitigate the current harms of climate change and the wrong moral assumptions that individuals make regarding their contribution to climate change. I discuss the principles of ethical consumerism, specifically in housing, food, and transportation. Lastly, I argue that climate change is an enforceable duty on the premise that those who cause or threaten harm are liable for their actions and that individuals are equally as liable for the collective well-being. -

Literally, Stories of Climate Change

NONPROFIT CIVIL SOCIETY CSR SOCIAL ENTERPRISE PHILAntHropy 18 Winds of Change 24 The Birds and the Bees: Lessons from a Social Enterprise 36 Face-Off: End-of-Life Ideas for Plastic 52 Short Fiction: Monarch Blue Edition 27 | JAN-MAR 2019 | /AsianNGO | www.asianngo.org/magazine | US$10 It’s not all doom and gloom Find nature conservation stories with a happy ending at: Table of Contents 24 the Birds and the Bees: LessOns FrOm a SociaL enterPrise 34 PhOtO FEATURE: Last Forest Enterprises is a social initiative based in South India that supports communities dependent on biodiversity for their livelihood. iMPACT traces their women and the journey, and some lessons they learned along the way. envirOnment PHOTO CREDITS Graphics, stock photos by flaticon.com, freepik.com, 123rf.com, Pixabay, Unsplash, Pexels, Ten Photos to Shake the World and Getty Images • Aadhimalai Pazhangudiyinar Producer Co. Ltd. • ABC Central Victoria: Larissa Romensky • B&T Magazine • BioCote • Canopy • Colossal • Conservation International • Digital Green 18 Winds of change 37 Face-Off: end- • Endangered Emoji/World Wide Fund For Nature • Florence Geyevu of-LiFe ideas for • Ian Kelly Jamotillo Renewable energy, despite its promise • Last Forest Enterprises of a cleaner planet, is not without its • Lensational PLastic • Misper Apawu problems. Meera Rajagopalan explores • National Wildlife Federation wind energy and its effect on bird Plastic pollution is putting countries • Sanna Lindberg in danger, yet improper waste • SDF fatalities, and how organizations such • Sasmuan Bankung Malapad Critical Habitat as Birdlife International promote clean disposal continues. iMPACT takes a Ecotourism Area (SBMCHEA) look at three possible solutions for • The Elephants & Bees Project / Lucy King energy from a biodiversity prospective. -

Annual Report 2019

2019 ANNUAL REPORT Outgoing President’s Address Since its founding in 1999, Centre for a Responsible Future (CRF) – originally Vegetarian Society (Singapore) – has been an important part of the Singapore story. I joined in 2002. Over time, I have performed various roles in the organization, and I look forward to continuing my work with CRF in the future. I derive a great deal of satisfaction from being a small part of the big things CRF does. I’m very happy that Desmond Koh has agreed to become CRF President. When we asked him to come on board, it was a case of “Nothing ventured, nothing gained”; so, it was a very pleasant surprise when Desmond said “Yes”. Desmond’s task is a difficult one, because we have grown significantly since our early days, as has the entire plant-based space. Thus, I call on everyone to do what you can to support Desmond and the other devoted members of the CRF leadership team. Your support can take many forms: time, talent, funds and good will. Our efforts at CRF have never been more crucial. Thanks for all you do, and see you at future CRF events. George Jacobs, PhD (Outgoing) President, Centre for a Responsible Future Incoming President’s Address First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to our beloved outgoing President George for his incredible leadership over the past 18 years. When I first decided to take on this responsibility, I knew that I would never truly be able to fill the shoes he left behind. -

Ethical Consumerism and Canadians

Ethical Consumerism and Canadians Part 2 of the Corporate and Community Social Responsibility Research Series A survey of 1,362 Canadians Conducted from November 29 to December 2, 2010 Conducted for: The Corporate and Community Social Responsibility Conference at Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ontario www.abacusdata.ca About the Research Series Abacus Data and the Corporate and Community Social Responsibility Conference A have partnered to produce a series of public opinion and market research studies BOUT on CCSR in Canada. CCSR is a growing area of interest not only for corporations but also for community organizations, social enterprises, consumers, and government. THE There is a significant amount of research data from American and European R sources. ESEARCH The intent of this six-part research series is to gather data from Canadians by Canadians over a 12-month period. It will give us a Canadian perspective on corporate and community social responsibility and allow us to track attitudes and behaviour over time. S In October 2010, a benchmark study was conducted and the results released at the ERIES CCSR Conference held at Algonquin College in Ottawa on November 16, 2010. It examined opinions and behaviour of Canadian consumers towards CCSR. Topic Expected Release Date Canadian Benchmark Survey October 2010 Ethical consumerism January 2011 Ethical employment and February 2011 compensation Individual social responsibility April 2011 Ethical investing August 2011 Canadian Benchmark Survey and October 2011 Global Comparisons For more information about this series, please contact David Coletto at [email protected] CCSR Research Series Survey Methodology M ETHODOLOGY From December 3rd to 6th, 2010, Abacus Data Inc. -

The Global Challenge of Sustainable Development – Local

Summary of Learning from “The Global Challenge of Sustainable Development – Local Implementations at European Academy of Otzehousen, Germany, May 12-19, 2017” and Plan for the Future Use of the Knowledge Obtained By M. A. Karim Department of Civil and Construction Engineering, KSU It was a great experience for me to participate in the above subject workshop with KSU colleagues. As an Environmental engineer and as an Environmental Engineer faculty it was a great deal for me. ‘Sustainability’ is a buzzword that is used almost in every discipline. Moving towards sustainability is a social challenge that entails international and national law, urban planning and transport, local and individual lifestyles and ethical consumerism. Ways of living more sustainably can take many forms from reorganizing living conditions for example, ecovillages, eco- municipalities and sustainable cities, reappraising economic sectors (permaculture, green building, sustainable agriculture), or work practices (sustainable architecture), using science to develop new technologies (green technologies, renewable energy and sustainable fission and fusion power), or designing systems in a flexible and reversible manner, and adjusting individual lifestyles that conserve natural resources. I always viewed the term 'sustainability' as humanity's target goal of human-ecosystem equilibrium (homeostasis), while 'sustainable development' refers to the holistic approach and temporal processes that lead us to the end point of sustainability. Despite the increased popularity of the use of the term "sustainability", the possibility that human societies seem to achieve environmental sustainability has been, and continues to be, questioned—in light of environmental degradation, climate change, overconsumption, population growth and societies' pursuit of indefinite economic growth in a closed system. -

Negotiating Ethical Consumerism in Everyday Life

NEGOTIATING ETHICAL CONSUMERISM IN EVERYDAY LIFE by Tracey Bedford RESOLVE Working Paper 13-11 1 The Research Group on Lifestyles, Values and Environment (RESOLVE) is a novel and exciting collaboration located entirely within the University of Surrey, involving four internationally acclaimed departments: the Centre for Environmental Strategy, the Surrey Energy Economics Centre, the Environmental Psychology Research Group and the Department of Sociology. Sponsored by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) as part of the Research Councils’ Energy Programme, RESOLVE aims to unravel the complex links between lifestyles, values and the environment. In particular, the group will provide robust, evidence-based advice to policy-makers in the UK and elsewhere who are seeking to understand and to influence the behaviours and practices of ‘energy consumers’. The working papers in this series reflect the outputs, findings and recommendations emerging from a truly inter-disciplinary research programme arranged around six thematic research strands: Carbon Footprinting: developing the tools to find out which bits of people’s lifestyles and practices generate how much energy consumption (and carbon emissions). Psychology of Energy Behaviours: concentrating on the social psychological influences on energy-related behaviours, including the role of identity, and testing interventions aimed at change. Sociology of Lifestyles: focusing on the sociological aspects of lifestyles and the possibilities of lifestyle change, exploring the role of values and the creation and maintenance of meaning. Household change over time: working with individual households to understand how they respond to the demands of climate change and negotiate new, low-carbon lifestyles and practices. Lifestyle Scenarios: exploring the potential for reducing the energy consumption (and carbon emissions) associated with a variety of lifestyle scenarios over the next two to three decades. -

Animal Rights and Food : Beyond Regan, Beyond Vegan

This is a repository copy of Animal rights and food : beyond Regan, beyond vegan. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/157942/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Milburn, J. orcid.org/0000-0003-0638-8555 (2016) Animal rights and food : beyond Regan, beyond vegan. In: Rawlinson, M. and Ward, C., (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics. Routledge . ISBN 9781138809130 https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315745503 This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics on 1st July 2016, available online: https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Handbook-of-Food-Ethics/Rawlinson-Ward/p/bo ok/9781138809130 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Animal Rights and Food: Beyond Regan, Beyond Vegan Josh Milburn This is a draft version of a paper appearing in The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics, edited by Mary C. -

Ethical Consumerism: an Oxymoron? with Many Arguing for More Radical, Systemic Change

increasingly being asked about the pace of change, Ethical consumerism: an oxymoron? with many arguing for more radical, systemic change. How can we grow people’s influence on the In a few sectors, a large proportion of products sold are food system beyond the point of purchase? now certified in the UK e.g. ‘ethical’ tea and organic baby food. However, even if all markets were certified and labelled as ‘ethical’ in the future, that might not The current landscape equate to food systems being fair and sustainable. Too often with current certification, the ‘process is The rise of ethical consumers becoming the purpose’. The notion of the ‘ethical consumer’ in the UK arguably emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s, symbolised Going beyond what the consumer wants by the Ethical Consumer magazine launching in 1989 – albeit values-driven consumption of food and drink has There are also limitations of food businesses only existed for much longer. The term ‘ethical’ means focusing on what consumers want. different things to different people – from ‘doing no For starters, there is no consensus as to what the top harm’ to ‘having a positive impact on others’. What ethical priority is (or should be). Well-intentioned constitutes harm is often contested, which is one concerns voiced by the public do not often recognise reason why we need healthy discourse and explicit unintended consequences of a single-issue focus. justification of courses of action. There are also many important issues which get little Ethical food buying is assumed to still be niche, but that ‘consumer response’, e.g. -

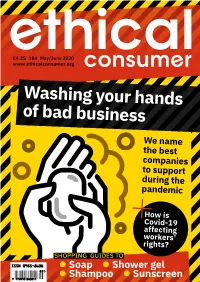

Ethical Consumer, Issue 184, May/June 2020

£4·25 184 May/June 2020 www.ethicalconsumer.org Washing your hands of bad business We name the best companies to support during the pandemic How is Covid-19 affecting workers’ rights? SHOPPING GUIDES TO l Soap l Shower gel l Shampoo l Sunscreen 2 Ethical Consumer May/June 2020 ETHICAL CONSUMER Editorial WHO’S WHO e hope that this magazine have started a Crowdfunder to raise THIS ISSUE’S EDITOR Tim Hunt finds you safe and well in money to help get essentials delivered to PROOFING Ciara Maginness (Little Blue Pencil) WRITERS/RESEARCHERS Jane Turner, Tim Hunt, these extraordinary times. people, alongside unions and grassroots Rob Harrison, Anna Clayton, Josie Wexler, For many, this is a period organisers operating in the area who Ruth Strange, Mackenzie Denyer, Clare Carlile, Wof extreme distress and anxiety. Loved we have come to know through our Francesca de la Torre, Alex Crumbie, Tom Bryson, ones may be sick, money may be tight, work. More details can be found on page Billy Saundry, Jasmine Owens REGULAR CONTRIBUTORS Simon Birch, Colin Birch and mental health may be suffering. The 47 and we hope that you will be in a DESIGN Tom Lynton list of problems caused by coronavirus position to donate, if you haven’t already. LAYOUT Adele Armistead (Moonloft), Jane Turner could fill a magazine (or a book). The generosity shown by many people COVER Tom Lynton In this issue, we’ve looked in depth at in the first hours of this appeal, (we CARTOONS Marc Roberts, Andy Vine, Mike Bryson, the impact of the coronavirus (and the reached our first target after just 4 Richard Liptrot subsequent lockdown) on the workers hours), also perhaps points towards the AD SALES Simon Birch SUBSCRIPTIONS Elizabeth Chater, who supply our modern consumer possibilities for a post-Covid world – a Francesca Thomas, Nadine Oliver markets, both in the UK and abroad.