Geographies of Corporate Philanthropy: the Northern Rock Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

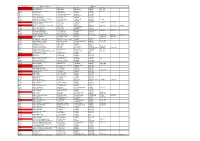

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation HY 2020 Our Investment Case 1 2 3 4 Our distinctive The scale and A well-positioned Our operational business model & quality of our development expertise & clear strategy portfolio pipeline customer insight Increasing our focus 22.5m sq ft of Development pipeline Expertise in on mixed use places high quality assets aligned to strategy managing and leasing our assets based on our customer insight Growing London Underpinned by our Provides visibility campuses and resilient balance sheet on future earnings Residential and refining and financial strength Drives incremental Retail value for stakeholders 1 British Land at a glance 1FA, Broadgate £15.4bn Assets under management £11.7bn Of which we own £521m Annualised rent 22.5m sq ft Floor space 97% Occupancy Canada Water Plymouth As at September 2019 2 A diverse, high quality portfolio £11.7bn (BL share) Multi-let Retail (26%) London Campuses (45%) 72% London & South East Solus Retail (5%) Standalone offices (10%) Retail – London & SE (10%) Residential & Canada Water (4%) 3 Our unique London campuses £8.6bn Assets under management £6.4bn Of which we own 78% £205m Annualised rent 6.6m sq ft Floor space 97% Occupancy As at September 2019 4 Canada Water 53 acre mixed use opportunity in Central London 5 Why mixed use? Occupiers Employees want space which is… want space which is… Attractive to skilled Flexible Affordable Well connected Located in vibrant Well connected Safe and promotes Sustainable and employees neighbourhoods wellbeing eco friendly Tech Close to Aligned to -

Time to Touch up the CV? Beeb Launches Search for New Director General

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY PLOUGHING AHEAD 30 YEARS LATER THE WIMBLEDON LOOK LAND ROVER DISCOVERY TO HEAD BACK TO HITS A LANDMARK P24 MERTON HOME P26 TUESDAY 11 FEBRUARY 2020 ISSUE 3,553 CITYAM.COM FREE HACKED OFF US ramps up China TREASURY TO spat with fresh Equifax charges SET OUT CITY BREXIT PLAN EXCLUSIVE Beyond Brexit, it will also consider “But there will be differences, not CATHERINE NEILAN the industry’s future in relation to least because as a global financial cen- worldwide challenges such as emerg- tre the UK needs to keep pace with @CatNeilan ing technologies and climate change. and drive international standards. THE GOVERNMENT will insist on the Javid sets out the government’s Our starting point will be what’s right right to diverge from EU financial plans to retain regulatory autonomy for the UK.” services regulation as part of a post- while seeking a “reliable equivalence He also re-committed to concluding Brexit trade deal with Brussels. process”, on which a “durable rela- “a full range of equivalence assess- Writing exclusively in City A.M. today, tionship” can be built. ments” by June of this year, in order to chancellor Sajid Javid says the “Of course, each side will only give the system sufficient stability City “will no longer be a rule- grant equivalence if it believes ahead of the end of transition. taker” and reveals that the other’s regulations are One senior industry figure told City ministers are working on compatible,” the chancel- A.M. that while a white paper was EMILY NICOLLE Zhiyong, Wang Qian, Xu Ke and Liu Le, a white paper setting lor writes. -

What's the Best Way to Get in Touch with My Banks?

INVESTIGATION | CONTACTING BANKS What’s the best way to get in touch with my bank? With more than 2,000 branches closing over the past decade, In part, banks and building societies have been cutting costs as a result of the financial has it become harder to access your bank, or do new contact crisis, or prioritising investment in technology methods compensate for the decline in face-to-face service? to get people banking in other ways. To better understand this shift in banking decade ago, if you wanted to pay in a The rapid rate of branch closure is a cause access, we surveyed 14 of the biggest current cheque or withdraw some money, all for concern for 57% of Which? members, account providers to find out how many A it would take was a short walk to your according to our survey of 1,356 people in branches they’d closed or opened between local high street bank branch. But today, the January 2014. However, with 89% of those we 2003 and 2013. We also asked about their same transaction at your nearest branch surveyed having access to online banking and branch network plans for 2014 and beyond. might require a 20-mile drive. 76% using telephone banking, it’s perhaps no HSBC closed the largest percentage – almost Given that the number of bank branches surprise that 42% believe that branch banking 30% were shut between the start of 2003 and on our high streets has almost halved since is becoming obsolete. But do the alternatives the end of 2013 – 458 branches in areas where the late 1980s, that’s hardly surprising. -

PLACES PEOPLE PREFER Annual Report and Accounts 2020

PLACES PEOPLE PREFER Annual Report and Accounts 2020 British Land plc Annual Report and Accounts 2020 Inside Key figures Strategic Report Underlying EPS IFRS loss after tax At a glance 2 Chairman’s statement 4 32.7p £(1,114)m Our purpose 6 2019: 34.9p 2019: £(320)m Case study: 1 Triton Square 8 Chief Executive’s review 10 Investment case 13 EPRA NAV per share Underlying Profit Business model 14 774p £306m Places 2019: 905p 2019: £340m Our portfolio 16 Strategic focus 22 Total accounting return IFRS net assets Strategic performance and KPIs 24 Development pipeline 26 (11.0)% £7,147m 2019: (3.3)% 2019: £8,689m People Customer and community stories 30 Stakeholder engagement and s172 32 IFRS EPS Dividend per share People and culture 34 (110.0)p 15.97p Employee-led networks 36 Sustainability 38 2019: (30.0)p 2019: 31.00p Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) 42 Senior unsecured Carbon intensity reduction GHG emissions 46 credit rating versus 2009 Non-financial reporting disclosure 47 A 73% Prefer 2019: A 2019: 64% Market insights 54 Performance review 56 Customer Bright Lights skills and Financial review 68 satisfaction employment programme Financial policies and principles 75 Managing risk 78 8.3 504 Principal risks 82 2019: 8.2/10 people supported with work Viability statement 88 2019: 389 Corporate Governance Report Chairman’s introduction 90 Board of Directors 92 Stakeholder engagement statement 96 Presentation of financial information Corporate Governance Report 98 The Group financial statements are prepared under IFRS where the Report of the Nomination Committee 104 Group’s interests in joint ventures and funds are shown as a single line item on the income statement and balance sheet and all subsidiaries are Report of the Audit Committee 108 consolidated at 100%. -

Nationwide Building Society

PROSPECTUS dated 11 September 2017 THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in doubt as to the action you should take in connection with this document or the proposals contained in it, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, if you are taking advice in the United Kingdom, or from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser if you are taking advice in a jurisdiction outside the United Kingdom. This document comprises a prospectus (the Prospectus) relating to Nationwide Building Society (the Society) and to the Society and its consolidated subsidiaries (Nationwide or the Group) prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, as amended (the FSMA). The Prospectus will be made available to the public in accordance with the Prospectus Rules. Capitalised terms used in this Prospectus which are not otherwise defined have the meanings given to them in “Part XXII: Definitions”. NATIONWIDE BUILDING SOCIETY (incorporated in England and Wales under the UK Building Societies Act 1986, as amended, and regulated by the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority with FCA Mutuals Public Register Number 355B) Issue of 5,000,000 Core Capital Deferred Shares of £1 each at an Issue Price of £159.00 per Core Capital Deferred Share (the Further CCDS) and admission of the Further CCDS to the Official List and to trading on the London Stock Exchange such Further CCDS to be consolidated and form a single series immediately upon issue with the 5,500,000 CCDS issued by the Society on 6 December 2013 (the Existing CCDS and, together with the Further CCDS, the CCDS) Joint Bookrunners Barclays BofA Merrill Lynch Citigroup J.P. -

BYY Overview

Best Year Yet closes the Performance Gap The Best Year Yet Program is a year long planning and execution “The pragmatic process that will close the Gap between your strategy and your approach and the performance. discipline that comes with the monthly follow up sessions has really helped my team to achieve the results we needed” Marketing Manager, Unilever “Bottom line results are up 60% over the past two years!” CEO, Unum Limited Dorking “Our team moved from last in the country to first” David McAvoy, Regional Director, NatWest Retail Bank Harvard Business Review , Turning Strategy into Great Performance “Best Year Yet is a focused system The program will facilitate your team in deciding what is important, that changes set objectives that are aligned around top initiatives, hold them behavior, culture accountable, and build in discipline to deliver the results that are and performance time after time” needed to reach higher levels of performance. Lawrence Churchill, Former CEO, Zurich Organisations of all sizes The process is perfect for: Financial Services • Senior leadership teams • Breakthrough sales results References • Project teams • Improving productivity Abbott, Proctor & Gamble, Zurich, • Organisations seeking to • Strategic planning & implementation Microsoft, ING, Swiss cascade accountability • Organisational transformation Life, American Express, • Derailed teams • Employee satisfaction & development HSBC, KPN, Bank of • Non performing teams • Morale, motivation, alignment & focus Ireland, IBM, Heineken, Unilever, Nestle, Coca-Cola, Halifax, Lloyd’s bank www.bestyearyet.com How is Best Year Yet structured? There are three basic components to the BYY program. Best Year Yet for management teams or departments, Best Year Yet for individuals, and the Follow-up Process. -

The Recent Evolution of the UK Banking Industry and Some Implications for Financial Stability

The recent evolution of the UK banking industry and some implications for financial stability Alex Bowen, Glenn Hoggarth and Darren Pain 1. Introduction The UK financial system experienced significant structural change during the 1970s and 1980s. Before then the system was segmented. Different institutions existed to provide the differentiated services of commercial banking, investment banking, housing finance, life assurance, fund management and securities trading. Within the banking sector, there was a clear demarcation between clearing banks which provided commercial banking facilities and money transmission services largely to domestic customers, investment banks which provided a range of largely market intermediated financial services to both domestic and overseas corporate clients such as equity issuance and portfolio investment advice, and building societies which were the main source for housing finance. These demarcations were maintained by various forms of official regulation such as exchange controls and lending constraints (including credit ceilings), which served to restrict competition and thus impart stability to the oligopolistic structure of the market. Changes to the institutional architecture took place progressively over the 1970s and 1980s. This was largely an evolutionary process, but a number of factors contributed to an intensification of competition and tended to erode the functional distinctions between firms. Five in particular are worth noting. First, the entry of foreign banks, associated with the continued growth in the eurodollar market and London's prominent role in this market, prompted the major clearing banks to expand their businesses into non-traditional markets such as corporate and unsecured lending. Initially, this was typically achieved through acquisitions in order to circumvent existing credit control regulations. -

BANK and BANKING the Art of Better Retail Banking Supportable

P1: FCG/SPH P2: FCG/SPH QC: FCG/SPH T1: SPH JWBK008-FM JWBK008-Croxford February 8, 2005 20:56 THE ART OF BETTER RETAIL BANKING Supportable Predictions on the Future of Retail Banking Hugh Croxford Frank Abramson Alex Jablonowski JOHN WILEY & SONS, LTD v P1: FCG/SPH P2: FCG/SPH QC: FCG/SPH T1: SPH JWBK008-01 JWBK008-Croxford January 14, 2005 18:54 16 P1: FCG/SPH P2: FCG/SPH QC: FCG/SPH T1: SPH JWBK008-FM JWBK008-Croxford February 8, 2005 20:56 “A whistle-stop tour of all aspects of retail banking. This is a very readable and insightful real world mix of theory, strategy, tactics and practice. They have even managed to make banking sound exciting. But mostly they have been able to cut through the complexity to remind us all that success in retail banking is not just about finance and efficiency – it is about customers and staff, who are all too often forgotten about.” Craig Shannon, Executive Director – Marketing, Co-operative Financial Services “The authors live up to their promise of providing managers and students with a clear exposition of the retail banking sector and how banks can confront the challenging future they face. This book is a practical manual with lots of useful advice. I was looking for new insights in this book – and I found them!” Professor Adrian Payne, Professor of Services Marketing, Director, Centre for Services Management, Cranfield School of Management “A key determinant of any organisation’s success will be an enhanced understanding of ‘value’ as defined by customers, employees, shareholders and other stakeholders. -

List of Active Members

List of Active Members ISVA The professional Society for Valuers and Auctioneers ACTIVE MEMBERS Abb-AIg Abbott, Dominic Charles, FRICS FSVA Adams, Richard John, FRICS FSVA Brogden &: Co, 38-39 Silver Street, Adams, Richard, 23 Warwick Row, Coventry, West Lincoln LN2 1EM Midlands CV1 lEY Tel No. 01522 531321 Tel No. 01203 251737 Elected 1975 Elected 1990 Ablitt, Ernest Henry, FSVA Adams, Roger Ian, FSVA Elected 1953 Elected 1979 Abrahams, Abi, ASVA Adamson, Gaye Elizabeth, DipVEM ASVA Elected 1994 Elected 1990 Abrahams, Peter David, FSVA Addison, Roy Matthew, DipREM ARICS ASVA Abrahams Consolidated Ltd, 51 London Road, Russell Baldwin &: Bright, (Chancellors Associates), St Albans, Hertfordshire AL11LJ 20 King Street, Hereford HR4 9DB Tel No. 01727 840111 Tel No. 01432 266663 Elected 1976 Elected 1989 Adetula, Francis Olajide Ipadeola, FSVA ARVA Abson, Stephen Paul Robert, ASVA ANAEA AlAS Elected 1995 Elected 1975 Acock, Malcolm Trevor, FSVA Aggett, Paul Anthony, ASVA Elected 1966 Ekins, 73 High Street, Burnham, Slough, Berkshire SL1 7jX Acquier, Andrew Francis, BA FSVA Tel No. 01628 604477 Andrew F Acquier, 6 Queen Street, Godalming, Elected 1981 Surrey GU7 1BD Tel No. 01483 424128 Agnew, Julian Michael, ASVA Elected 1979 Jones Lang Wootton, 22 Hanover Square, London W1A 2BN Acton, Martin Howard Harrison, ASVA Tel No. 0171 493 6040 Healey &: Baker, 29 St George Street, Hanover Elected 1988 Square, London W1A 3BG Tel No. 0171 6299292 Ahmed, Faida Yasmin, BSc ARICS ASVA Elected 1987 Elected 1995 Adams, John Alfred, FRICS FSVA Ainge, James Leonard, JP FSVA IRRV Adams Burnett, 138 Buckingham Palace Road, Elected 1973 London SW1W 9SA Tel No. -

UK & EU Unsupported Banks

UK & EU Unsupported Bank List EU Unsupported Banks (Bank and Credit Cards only) UK Unsupported Banks (Bank and Credit Cards only) ABANCA (Business) (Spain) - Bank AA credit card (UK) ABANCA (Spain) - Bank AA Savings (UK) - Bank ABN AMRO (Netherlands) - Bank Abbey National (UK) - Credit Card ABN Amro Business Credit Card (Netherlands) Adam & Company (UK) - Bank Activo Bank (Portugal) Airdrie Savings Bank (UK) ActivoBank (Espana) - Banco Aldermore Business Bank (UK) Allied Irish Bank (Business) (Ireland) - Bank Aldermore Savings (UK) - Bank Allied Irish Bank (Business) (Ireland) - Credit Card Alliance & Leicester (UK) - Bank Allied Irish Bank (Ireland) - Bank Alliance & Leicester (UK) - Credit Card Allied Irish Bank (Ireland) - Credit Card Alliance Trust Savings (UK) - Bank American Express (Card Account) (Espana) - Tarjeta de Allied Irish Business Bank (UK) - Bank Credito American Express Card Amazon Credit Card (UK) American Express Cards (France) - Bank American Express Business Cards (UK) American Express Cards (Switzerland) American Express Cards (global) (UK) - Credit Card American Express Cards (Switzerland) American Express Cards (UK) American Express Cards DUTCH (Netherlands) - Bank American Express Cards Mobile (UK) - Credit Card American Express cards(NL) (Netherlands) - Credit Card aqua card (UK) American Express Credit Cards (Spain) Arbuthnot Latham (Current Account) (UK) - Bank ASN Bank (Netherlands) - Bank Arbuthnot Lathum (UK) - Bank ASN Bank (Netherlands) - Credit Card ASDA - Credit Cards (UK) AXA Banque (France) Bank of -

Bradford & Bingley Transformation & Decline

Bradford & Bingley Transformation & Decline: 1995 – 2010 Matthias Hambach PhD University of York The York Management School October 2014 Abstract The recent financial and economic crisis, which affected many financial institutions in the UK, created the need to investigate and understand how the crisis affected these institutions. Consequently, numerous official reports and academic studies have been written, particularly on Northern Rock, examining the financial impact on, and business strategies of, these institutions. However, comparatively, there has been little empirical investigation into the board processes that contributed to the decisions made by the management of these affected institutions leading up to the crisis. Of particular interest to research are the demutualised building societies. They were unlike the large universal banks, who engaged heavily in investment banking and were trading on their own account; yet their organisational outcomes, in particular receipt of government support, were similar. This study focuses on the case of the former Bradford & Bingley Building Society (B&B), the last building society to demutualise, and investigates its transformation and decline over the period 1995 – 2010. The investigation adopts a novel approach by combining the Corporate Governance Life-Cycle with the Upper Echelons Perspective to examine structural and behavioural changes of the board and its governance functions, during the transition of Bradford & Bingley, from building society to bank and nationalised institution. Using a variety of sources, including interviews with directors, official documents, financial records, and newspaper articles, the transformation of B&B is examined through a historical lens. The thesis argues that life-cycle stages should not be seen as periods with well defined boundaries, but rather overlapping periods of varying length, where each period has distinct characteristics that distinguish it from another.