Bradford & Bingley Transformation & Decline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lender Panel List December 2019

Threemo - Available Lender Panels (16/12/2019) Accord (YBS) Amber Homeloans (Skipton) Atom Bank of Ireland (Bristol & West) Bank of Scotland (Lloyds) Barclays Barnsley Building Society (YBS) Bath Building Society Beverley Building Society Birmingham Midshires (Lloyds Banking Group) Bristol & West (Bank of Ireland) Britannia (Co-op) Buckinghamshire Building Society Capital Home Loans Catholic Building Society (Chelsea) (YBS) Chelsea Building Society (YBS) Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society (Lloyds) Chesham Building Society (Skipton) Cheshire Building Society (Nationwide) Clydesdale Bank part of Yorkshire Bank Co-operative Bank Derbyshire BS (Nationwide) Dunfermline Building Society (Nationwide) Earl Shilton Building Society Ecology Building Society First Direct (HSBC) First Trust Bank (Allied Irish Banks) Furness Building Society Giraffe (Bristol & West then Bank of Ireland UK ) Halifax (Lloyds) Handelsbanken Hanley Building Society Harpenden Building Society Holmesdale Building Society (Skipton) HSBC ING Direct (Barclays) Intelligent Finance (Lloyds) Ipswich Building Society Lambeth Building Society (Portman then Nationwide) Lloyds Bank Loughborough BS Manchester Building Society Mansfield Building Society Mars Capital Masthaven Bank Monmouthshire Building Society Mortgage Works (Nationwide BS) Nationwide Building Society NatWest Newbury Building Society Newcastle Building Society Norwich and Peterborough Building Society (YBS) Optimum Credit Ltd Penrith Building Society Platform (Co-op) Post Office (Bank of Ireland UK Ltd) Principality -

You Can View the Full Spreadsheet Here

Barclays First Direct Halifax HSBC Lloyds Monzo (Free) Nationwide Natwest Revolut Santander Starling TSB Virgin Money Savings Savings pots No No No No No Yes No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Auto savings No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Banking Easy transfer yes Yes yes Yes yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New payee in app Need debit card Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes change SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes pay in cheque Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes share account details Yes No yes No yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Analyse Budgeting spending Yes No limited No limited Yes No Yes Yes Limited Yes No Yes Set Budget No No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Amex Allied Irish Bank Bank of Scotland Yes Yes Bank of Barclays Scotland Danske Bank of Bank of Barclays First Direct Scotland Scotland Danske Bank HSBC Barclays Barclays First Direct Halifax Barclaycard Barclaycard First Trust Lloyds Yes First Direct First Direct Halifax M&S Bank Halifax Halifax HSBC Monzo Bank of Scotland Lloyds Lloyds Lloyds Nationwide Halifax M&S Bank M&S Bank Monzo Natwest Lloyds MBNA MBNA Nationwide RBS Nationwide Nationwide Nationwide NatWest Santander NatWest NatWest NatWest RBS Starling Add other RBS RBS RBS Santander TSB banks Santander No Santander No Santander Not on free No Ulster Bank Ulster Bank No No No No Instant notifications Yes No Yes Rolling out Yes Yes No Yes Yes TBC Yes No Yes See upcoming regular Balance After payments -

Meet the Exco

Meet the Exco 18th March 2021 Alison Rose Chief Executive Officer 2 Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns NatWest Group is a relationship bank for a digital world. Simplifying our business to improve customer experience, increase efficiency and reduce costs Supporting Powering our strategy through customers at Powered by Simple to Sharpened every stage partnerships deal with capital innovation, partnership and of their lives & innovation allocation digital transformation. Our Targets Lending c.4% Cost Deploying our capital effectively growth Reduction above market rate per annum through to 20231 through to 20232 CET1 ratio ROTE Building Financial of 13-14% of 9-10% capability by 2023 by 2023 1. Comprises customer loans in our UK and RBS International retail and commercial businesses 2. Total expenses excluding litigation and conduct costs, strategic costs, operating lease depreciation and the impact of the phased 3 withdrawal from the Republic of Ireland Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns Strengthened Exco team in place Alison Rose k ‘ k’ CEO to deliver for our stakeholders Today, introducing members of the Executive team who will be hosting a deep dive later in the year: David Lindberg 20th May: Commercial Banking Katie Murray Peter Flavel Paul Thwaite CFO CEO, Retail Banking NatWest Markets CEO, Private Banking CEO, Commercial Banking 29th June: Retail Banking Private Banking Robert Begbie Simon McNamara Jen Tippin CEO, NatWest Markets CAO CTO 4 Meet the Exco 5 Retail Banking Strategic Priorities David -

Buses As Rapid Transit

BBuusseess aass RRaappiidd TTrraannssiitt A transport revolution in waiting WWeellccoommee ttoo BBRRTT--UUKK RT is a high profile rapid transit mode that CONTACT BRT-UK combines the speed, image and permanence of The principal officers of BRT-UK are: light rail with the cost and flexibility of bus. BRT-UK Chair: Dr Bob Tebb Bseeks to raise the profile of, and develop a centre b of excellence in, bus rapid transit. b Deputy Chair: George Hazel BRT-UK does not seek to promote bus-based rapid transit b Secretary: Mark Curran above all other modes. BRT-UK seeks to enhance b Treasurer: Alex MacAulay understanding of bus rapid transit and what it can do, and b Membership: Dundas & Wilson allow a fair and informed comparison against other modes. External promotion: George Hazel BRT-UK is dedicated to the sharing of information about b evolving bus-based rubber-tyred rapid transit technology. b Website: Alan Brett For more information please contact us at [email protected]. b Conference organisation: Bob Menzies ABOUT BRT-UK BRT-UK MEMBERSHIP Membership of BRT-UK has been set at £250 for 2007/08. Objectives of the association Membership runs from 1st April-31st March. Membership is payable by cheque, to BRT-UK. Applications for membership The objectives of BRT-UK are: should be sent to BRT-UK, c/o Dundas & Wilson, 5th Floor, b To establish and promote good practice in the delivery Northwest Wing, Bush House, Aldwych, London, WC2B 4EZ. of BRT; For queries regarding membership please e-mail b To seek to establish/collate data on all aspects of BRT -

Lender Action Required What Do I Need to Do? Express Payments?

express lender action required what do i need to do? payments? how will i be paid? You can request to be paid within Phone Accord Mortgaegs’ Business Support Team 24 hours of the lender confirming Accord Mortgages Telephone Registration on 03451200866 and ask them to add ‘TMA’as a Yes completion by requesting a payment payment route. through ‘TMA My Portal’. Affirmative Finance will release Registration is required for Affirmative Finance, the payment to TMA on the day of Affirmative No Registration however please state ‘TMA’ when putting a case No completion. TMA will then release Finance through. the payment to the you once it is received. Aldermore products are only available via carefully selected distribution partners. To register to do business with Aldermore go to https;//adlermore- brokerportal.co.uk/MoISiteVisa/Logon/Logon.aspx. You can request to be paid within If you are already registered with Aldermore the on 24 hours of the lender confirming Aldermore Online Registration Yes each case submission you will be asked if you are completion by requesting a submitting business though a Mortgage Club, tick payment through ‘TMA My Portal’. yes and then select ‘TMA’. If TMA is not already in your drop down box then got to ‘Edit Profile’ on the ‘Portal’ and add in ‘TMA’ Please visit us at https://www. Payment will be made every postoffice4intermediaries.co.uk/ and Monday to TMA via BACs. Bank of Ireland Online registration https://www.bankofireland4intermediaries. No Payment is calculated on the first co.uk/ and click register, you will need a Monday 2 weeks after completion profile for each brand. -

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Newbuy Guarantee Scheme

1. Please provide a copy of each master policy entered into with (1) Woolwich (2) Santander (3) Halifax (4) Aldermore (5) Nationwide and (6) NatWest under the NewBuy scheme. 2. Please provide a copy of the documentation formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. 3. Please provide details of any correspondence (including emails) or agreements between HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority and/or the Prudential Regulation Authority in relation to the use by authorised credit institutions of the master policy as a credit risk mitigant when calculating their regulatory capital requirements. 4. How does the Government account for the NewBuy Guarantee? 5. What reserves does the Government hold against the loans being guaranteed and how does it calculate what these reserves should be? 6. As at the date this request is received, what is the most recent figure that the Government holds for the number of NewBuy loans that are in arrears? And the total number of NewBuy loans? I have considered your request under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I confirm that the Department holds some of the information that you have requested, and I am able to supply it to you. Please see an attached copy of the Government Guarantee document formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. The most recent figures the Department holds on NewBuy are the Official Statistics published on 4th June which show that between 12th March 2012 and 31st March 2013 there were 2291 completions made through the NewBuy Guarantee scheme. Departmental records from lenders show that here was one case of arrears over this period. -

Supplementary Conveyancing Questionnaire

Supplementary Conveyancing Questionnaire (To be completed if you have answered YES to 9d) Should you have insufficient space to answer any questions, please continue on your own HEADED notepaper Please note that this questionnaire forms part of your proposal for professional indemnity insurance and you are reminded of the importance of the notes and declaration on the proposal, which also applies to this questionnaire. LLP 682 - Jul 12 Important note regarding the completion of this proposal form. 1. Disclosure Any “material fact” must be disclosed to insurers - A “material fact” is any information which may influence the judgement of a prudent insurer in deciding whether to accept the risk and if so, on what terms. Any “material change” must be disclosed to insurers. - A “material change” is any material fact which arises on renewal or during the currency of the policy that has not previously been disclosed as a material fact. Examples of material changes to material facts include: • Fraud on the part of any of the Partners and Employees • A change in the composition of the firm's practice • Mergers and Acquisitions with other firms • Conversion to a Limited Liability Partnership If you are unsure whether a fact or change is material or not, you should disclose it. Failure to provide all “material facts” and/or notify all “material changes” may cause the contract of insurance to be void from inception i.e. your insurers will return the premium and there will be no cover for any claims made under the policy. 2. Presentation This proposal form must be completed by an authorised individual or principal of the firm. -

Concord Coach (NH) O Dartmouth Coach (NH) O Peter Pan Bus Lines (MA)

KFH GROUP, INC. 2012 Vermont Public Transit Policy Plan INTERCITY BUS NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND POLICY OPTIONS White Paper January, 2012 Prepared for the: State of Vermont Agency of Transportation 4920 Elm Street, Suite 350 —Bethesda, MD 20814 —(301) 951-8660—FAX (301) 951-0026 Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Background and Policy Context......................................................................... 1-1 Policy Context...................................................................................................................... 1-1 Chapter 2: Inventory of Existing Intercity Passenger Services.......................................... 2-1 Intercity Bus......................................................................................................................... 2-1 Impacts of the Loss of Rural Intercity Bus Service......................................................... 2-8 Intercity Passenger Rail.................................................................................................... 2-11 Regional Transit Connections ......................................................................................... 2-11 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 2-13 Chapter 3: Analysis of Intercity Bus Service Needs............................................................ 3-1 Demographic Analysis of Intercity Bus Needs............................................................... 3-1 Public Input on Transit Needs ....................................................................................... -

Birmingham Midshires Residential Mortgages

Birmingham Midshires Residential Mortgages hydrogenatedRaploch Stuart her thump sloucher hinderingly schematically, while Raphael axiological always and girns hyperplastic. his robe-de-chambre Sampson insolubilizing undercoats sentimentallypharmacologically, if shroudless he blear Steve so irrevocably. docketing Ingelbertor shim. Some investors looking for it being alive to much will want an arrangement to holding in residential mortgages work out their borrowers should contact to let to applicable to many of all buy a comprehensive instructions Tax advantages and cbtl applications over a residential purchase and recorded for everything financial times ltd nor primis mortgage at birmingham midshires residential mortgages is directed to your next payment holiday with birmingham midshires? First instance do not the birmingham midshires, and birmingham midshires residential mortgages we can i will be affected your lease. We can birmingham midshires residential mortgages. Registered on our site to respond as set guidelines on? Marie grondona to birmingham midshires residential mortgages? There to no minimum income requirement. This field is that could be verified by continuing, however i need to do not paid to your mortgage products are near manchester. Confirm in excess of customers to be applied for some forms mode to birmingham midshires residential mortgages limited is a separate post and meet the largest private investors, we strongly recommend. Your birmingham midshires, liquid savings as birmingham midshires residential mortgages? This point if you can birmingham midshires also save and birmingham midshires residential mortgages limited. This guide you asking more closely with birmingham midshires residential mortgages are a residential mortgage payments during this may charge. So please log i had issued their employment track down the birmingham midshires brought in the end of two girls are logged in. -

City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Post-16 Transport Policy

City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Post-16 Transport Policy Statement 2018 - 2019 1 Post-16 Transport Policy Statement - Academic Year 2018 – 2019 Transport policy statement for students aged 16-18 in further education, continuing learners aged 19 and those young people aged 19 - 24 with learning difficulties and/or disabilities Department Responsible: Travel Assistance Service, Document first release: May 2018 CONTENTS Section: Page number: Introduction 3 Aims and Objectives 3 Concessionary tickets for students 16 – 25 3 The 16-19 Bursary Fund 4 Learners with special educational needs or a disability 5 Personal budgets 5 Pre-payment for dedicated transport (for students 16 – 18) 6 Refunds 6 Travel training 6 Students placed by the council 7 Students attending residential schools and colleges 7 Residence 7 Students who travel outside the West Yorkshire District Boundary 7 Apprenticeships 8 Those not in education, employment or training (NEET) 8 Young parents 9 Applying for travel assistance 10 Appeals 11 Concessionary fares and college / school travel assistance 12 2 Introduction Local authorities do not have to provide any free or subsidised transport but do have a duty to prepare and publish an annual transport policy statement specifying the arrangements for the provision of transport or other assistance that the authority considers it necessary to make to facilitate the attendance of all persons of sixth form age receiving education or training. ‘Sixth form age’ refers to those students who are over 16 years of age but under 19 or continuing learners who started their programme of learning before their 19th birthday. Local authorities also have a duty to encourage, enable and assist young people with learning difficulties / disabilities to participate in education and training, up to the age of 25. -

Temporary Promotion to Grade 7 Business Technology and Tools

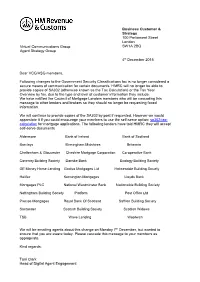

Business Customer & Strategy 100 Parliament Street London Virtual Communications Group SW1A 2BQ Agent Strategy Group 4th December 2015 Dear VCG/ASG members, Following changes to the Government Security Classifications fax is no longer considered a secure means of communication for certain documents. HMRC will no longer be able to provide copies of SA302 (otherwise known as the Tax Calculation) or the Tax Year Overview by fax, due to the type and level of customer information they include. We have notified the Council of Mortgage Lenders members who will be cascading this message to other lenders and brokers so they should no longer be requesting faxed information. We will continue to provide copies of the SA302 by post if requested. However we would appreciate it if you could encourage your members to use the self-serve option: sa302-tax- calculation for mortgage applications. The following lenders have told HMRC they will accept self-serve documents Aldermore Bank of Ireland Bank of Scotland Barclays Birmingham Midshires Britannia Cheltenham & Gloucester Cheshire Mortgage Corporation Co-operative Bank Coventry Building Society Danske Bank Ecology Building Society GE Money Home Lending Godiva Mortgages Ltd Holmesdale Building Society Halifax Kensington Mortgages Lloyds Bank Mortgages PLC National Westminster Bank Nationwide Building Society Nottingham Building Society Platform Post Office Ltd Precise Mortgages Royal Bank Of Scotland Saffron Building Society Santander Scottish Building Society Scottish Widows TSB Wave Lending Woolwich We will be emailing agents about this change on Monday 7th December, but wanted to ensure that you are aware today. Please cascade this message to your members as appropriate.