Landes and Dunes of Gascony (With Map and Illustrations)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Résumé Non Technique Général Du Zonage Assainissement Collectif

DEPARTEMENT DES PYRENEES ATLANTIQUES COMMUNAUTE D’AGGLOMERATION PAYS BASQUE (CAPB) PERIMETRE ADOUR URSUIA ZONAGE ASSAINISSEMENT COLLECTIF 16 COMMUNES RESUME NON TECHNIQUE GENERAL JUILLET 2020 Etabli par : 2AE Assistance Environnement Aménagement Technopole Hélioparc 2, Avenue Pierre Angot – 64053 PAU Cedex 9 [email protected] SOMMAIRE I. Les raisons du zonage de l’assainissement .............................................. 3 II. L’existant ............................................................................................. 4 III. Choix d’un assainissement collectif ou non-collectif .............................. 9 IV. Proposition de zonage ....................................................................... 11 2AE – ADOUR URSUIA – Zonages assainissement collectif – RESUME NON TECHNIQUE Page | 2 I. Les raisons du zonage de l’assainissement La mise en application de la Loi sur l’Eau du 3 janvier 1992 (article L2224-10 du code général des collectivités territoriales) fait obligation aux communes de définir un zonage de l’assainissement des eaux usées. Celui-ci délimite les zones d’assainissement collectif, c'est-à-dire où l’assainissement est réalisé par un réseau de collecte et d’une station d’épuration, et les zones d’assainissement non collectif qui correspondent à des installations individuelles (à la parcelle). L’assainissement non collectif est considéré comme une alternative à l’assainissement collectif dans les secteurs où ce dernier ne se justifie pas, soit du fait d’une absence d’intérêt pour l’environnement, soit -

Capital Implodes and Workers Explode in Flanders, 1789-1914

................................................................. CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 . --------- ---- --------------- --- ....................... - ---------- CRSO Working Paper [I296 Copies available through: Center for Research on Social Organization University of Michigan 330 Packard Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 Flanders in 1789 In Lille, on 23 July 1789, the Marechaussee of Flanders interrogated Charles Louis Monique. Monique, a threadmaker and native of Tournai, lived in the lodging house kept by M. Paul. Asked what he had done on the night of 21-22 July, Monique replied that he had spent the night in his lodging house and I' . around 4:30 A.M. he got up and left his room to go to work. Going through the rue des Malades . he saw a lot of tumult around the house of Mr. Martel. People were throwing all the furniture and goods out the window." . Asked where he got the eleven gold -louis, the other money, and the elegant walking stick he was carrying when arrested, he claimed to have found them all on the street, among M. Martel's effects. The police didn't believe his claims. They had him tried immediately, and hanged him the same day (A.M. Lille 14336, 18040). According to the account of that tumultuous night authorized by the Magistracy (city council) of Lille on 8 August, anonymous letters had warned that there would be trouble on 22 July. On the 21st, two members of the Magistracy went to see the comte de Boistelle, provincial military commander; they proposed to form a civic militia. -

Publication of an Application for Approval of Amendments, Which Are

20.1.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 18/39 Publication of an application for approval of amendments, which are not minor, to a product specification pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2020/C 18/09) This publication confers the right to oppose the amendment application pursuant to Article 51 of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council (1) within three months from the date of this publication. APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF NON-MINOR AMENDMENTS TO THE PRODUCT SPECIFICATION FOR A PROTECTED DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN OR PROTECTED GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION Application for approval of amendments in accordance with the first subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 ‘JAMBON DE BAYONNE’ EU No: PGI-FR-00031-AM01 — 11.9.2018 PDO ( ) PGI (X) 1. Applicant group and legitimate interest Consortium du Jambon de Bayonne Route de Samadet 64 410 Arzacq FRANCE Tel. +33 559044935 Fax +33 559044939 Email: [email protected] Membership: Producers/processors 2. Member State or third country France 3. Heading in the product specification affected by the amendment(s) Name of product Description of product Geographical area Proof of origin Method of production Link Labelling Other: data update, inspection bodies, national requirements, annexes 4. Type of amendment(s) Amendments to the product specification of a registered PDO or PGI not to be qualified as minor within the meaning of the third subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 Amendments to the product specification of a registered PDO or PGI for which a Single Document (or equivalent) has not been published and which cannot be qualified as minor within the meaning of the third subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 (1) OJ L 343, 14.12.2012, p. -

Fiche Synoptique-GARONNE-En DEFINITIF

Synopsis sheets Rivers of the World The Garonne and the Adour-Garonne basin The Garonne and the Adour-Garonne basin The Garonne is a French-Spanish river whose source lies in the central Spanish Pyrenees, in the Maladeta massif, at an altitude of 3,404 m. It flows for 50 km before crossing the border with France, through the Gorges du Pont-des-Rois in the Haute-Garonne department. After a distance of 525 km, it finally reaches the Atlantic Ocean via the Garonne estuary, where it merges with the river Dordogne. The Garonne is joined by many tributaries along its course, the most important of which are the Ariège, Save, Tarn, Aveyron, Gers, Lot, and others, and crosses regions with varied characteristics. The Garonne is the main river in the Adour-Garonne basin and France’s third largest river in terms of discharge. par A little history… A powerful river taking the form of a torrent in the Pyrenees, the Garonne’s hydrological regime is pluvionival, characterised by floods in spring and low flows in summer. It flows are strongly affected by the inflows of its tributaries subject to oceanic pluvial regimes. The variations of the Garonne’s discharges are therefore the result of these inputs of water, staggered as a function of geography and the seasons. In the past its violent floods have had dramatic impacts, such as that of 23 June 1875 at Toulouse, causing the death of 200 people, and that of 3 March 1930 which devastated Moissac, with around 120 deaths and 6,000 people made homeless. -

Pau, Your New Home

DISCOVER YOUR CITY Campus France will guide you through your first steps in France and exploring Pau, your new home. WELCOME TO PAU At Université de Pau, you must contact the ARRIVING Direction des Relations Internationales IN PAU / (05 59 40 70 54). National Services An International Welcome Desk for the university - students: www.etudiant.gouv.fr students - doctoral students, researchers: http://www.euraxess.fr/fr At Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour (UPPA), the Direction des Relations Internationales is tasked with greeting and advising international students. HOUSING An International Welcome Desk was put in place for all international, students, doctoral IN PAU / students, or researchers. There are numerous solutions for housing in Address: Direction des Relations Internationales, Pau: Student-only accommodations managed by International Welcome Desk, Domaine Universitaire, CROUS, student housing and private residences, 64000 Pau. and rooms in private homes. Hours: Monday to Thursday, 1:30pm to 4:30pm, Most important is to take care of this as early as Tuesday to Friday 9am to 12pm. possible and before your arrival. Email contact: [email protected] • The City of Pau site offers several tips: Learn more: http://www.pau.fr > Futur habitant > taper Logement - Consult the University international pages: étudiant https://ri.univ-pau.fr/fr/international-welcome- • The Nouvelle-Aquitaine CRIJ, Centre Régional desk.html UNIVERSITÉ DE PAU ET DES PAYS DE L’ADOUR Informations pratiques / Practical information / Informacion practica d’Information Jeunesse, the regional youth information Visa long séjour - titre de séjour Long-stay visa - residence permit / Visado de larga estancia - tarjeta de residente - Download the Guide d’Accueil Les étudiants de l’UE, de l’EEE ou de la Suisse Students belonging to the EU, the EEA and Los estudiantes de la UE, el EEE o Suiza no ne sont pas tenus d’avoir un tre de séjour Switzerland do not need a v isa to study in están obligados a c ontar con una tarjeta de pour étudier en France. -

MASSIF DU SIRON - CRÊTES DU MOURAS ET DE LA FUBIE - CRÊTES DU FRIGOURIAS (Identifiant National : 930020042)

Date d'édition : 27/10/2020 https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/930020042 MASSIF DU SIRON - CRÊTES DU MOURAS ET DE LA FUBIE - CRÊTES DU FRIGOURIAS (Identifiant national : 930020042) (ZNIEFF Continentale de type 2) (Identifiant régional : 04116100) La citation de référence de cette fiche doit se faire comme suite : Cédric DENTANT, Jean- Charles VILLARET, Luc GARRAUD, Stéphane BELTRA, Stéphane BENCE, Sylvain ABDULHAK, Emilie RATAJCZAK, Jérémie VAN ES, Sonia RICHAUD, .- 930020042, MASSIF DU SIRON - CRÊTES DU MOURAS ET DE LA FUBIE - CRÊTES DU FRIGOURIAS. - INPN, SPN-MNHN Paris, 7P. https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/930020042.pdf Région en charge de la zone : Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur Rédacteur(s) :Cédric DENTANT, Jean-Charles VILLARET, Luc GARRAUD, Stéphane BELTRA, Stéphane BENCE, Sylvain ABDULHAK, Emilie RATAJCZAK, Jérémie VAN ES, Sonia RICHAUD Centroïde calculé : 908953°-1914481° Dates de validation régionale et nationale Date de premier avis CSRPN : Date actuelle d'avis CSRPN : 26/09/2017 Date de première diffusion INPN : 23/10/2020 Date de dernière diffusion INPN : 23/10/2020 1. DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. CRITERES D'INTERET DE LA ZONE ........................................................................................... 3 3. CRITERES DE DELIMITATION DE LA ZONE .............................................................................. 4 4. FACTEUR INFLUENCANT L'EVOLUTION DE LA ZONE ............................................................ -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

3B2 to Ps.Ps 1..5

1987D0361 — EN — 27.05.1988 — 002.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COMMISSION DECISION of 26 June 1987 recognizing certain parts of the territory of the French Republic as being officially swine-fever free (Only the French text is authentic) (87/361/EEC) (OJ L 194, 15.7.1987, p. 31) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Decision 88/17/EEC of 21 December 1987 L 9 13 13.1.1988 ►M2 Commission Decision 88/343/EEC of 26 May 1988 L 156 68 23.6.1988 1987D0361 — EN — 27.05.1988 — 002.001 — 2 ▼B COMMISSION DECISION of 26 June 1987 recognizing certain parts of the territory of the French Republic as being officially swine-fever free (Only the French text is authentic) (87/361/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Having regard to Council Directive 80/1095/EEC of 11 November 1980 laying down conditions designed to render and keep the territory of the Community free from classical swine fever (1), as lastamended by Decision 87/230/EEC (2), and in particular Article 7 (2) thereof, Having regard to Commission Decision 82/352/EEC of 10 May 1982 approving the plan for the accelerated eradication of classical swine fever presented by the French Republic (3), Whereas the development of the disease situation has led the French authorities, in conformity with their plan, to instigate measures which guarantee the protection and maintenance of the status of -

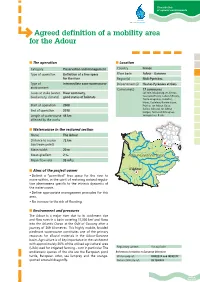

Agreed Definition of a Mobility Area for the Adour

Preservation of aquatic environments Agreed defi nition of a mobility area for the Adour ■ The operation ■ Location Category Preservation and management Country France Type of operation Defi nition of a free space River basin Adour - Garonne for the river Region(s) Midi-Pyrénées Type of Intermediate zone watercourse Département(s) Hautes-Pyrénées et Gers environment Commune(s) 17 communes Issues at stake (water, River continuity, Lafi tole, Maubourguet, Estirac, biodiversity, climate) good status of habitats Caussade-Rivière, Labatut-Rivière, Tieste-Uragnoux, Jû-Belloc, Hères, Castelnau-Rivière-Basse, Start of operation 2008 Préchac-sur-Adour, Goux, Galiax, Cahuzac-sur-Adour, End of operation 2018 Izotges, Termes-d’Armagnac, Length of watercourse 44 km Sarragachies, Riscle. affected by the works ■ Watercourse in the restored section Name The Adour Distance to source 72 km (upstream point) Mean width 20 m Mean gradient 2 ‰ Adour-Garonne basin Mean fl ow rate 35 m3/s ■ Aims of the project owner L'Adour • Delimit a “permitted” free space for the river to move within, in the spirit of restoring natural regula- tion phenomena specifi c to the intrinsic dynamics of the watercourse. • Defi ne appropriate management principles for this area. • No increase to the risk of fl ooding. ■ Environment and pressures The Adour is a major river due to its catchment size and fl ow rates in a basin covering 17,000 km2 and fl ows into the Atlantic Ocean at the Gulf of Gascony after a journey of 309 kilometres. This highly mobile, braided piedmont watercourse constitutes one of the primary resources for alluvial materials in the Adour-Garonne basin. -

Château Tour Prignac

Château Tour Prignac An everlasting discovery The château, Western front Research and texts realised by Yann Chaigne, Art Historian hâteau Tour Prignac was given its name by current owners the Castel Cfamily, shortly after becoming part of the group. The name combines a reference to the towers which adorn the Château and to the vil- lage of Prignac-en-Médoc, close to Lesparre, in which it is situated. With 147 hectares of vines, Château Tour Prignac is one of the largest vineyards in France today. The estate was once known as La Tartuguière, a name derived from the term tortugue or tourtugue, an archaic rural word for tortoise. We can only assume that the name alluded to the presence of tortoises in nearby waters. A series of major projects was undertaken very early on to drain the land here, which like much of the Médoc Region, was fairly boggy. The Tartuguière fountain, however, which Abbé Baurein described in his “Variétés borde- loises”, as “noteworthy for the abundance and quality of its water”, continues to flow on the outskirts of this prestigious Château. The history and architecture of the estate give us many clues to the reasons behind its present appearance. There is no concrete evidence that the Romans were present in the Médoc, neither is there any physical trace of a mediaeval Châ- teau at Tartuguière; it is probable, however, that a house existed here, and that the groundwork was laid for a basic farming operation at the end of the 15th century, shortly after the Battle of Cas- tillon which ended the Hundred Years War. -

The Demarcation Line

No.7 “Remembrance and Citizenship” series THE DEMARCATION LINE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE General Secretariat for Administration DIRECTORATE OF MEMORY, HERITAGE AND ARCHIVES Musée de la Résistance Nationale - Champigny The demarcation line in Chalon. The line was marked out in a variety of ways, from sentry boxes… In compliance with the terms of the Franco-German Armistice Convention signed in Rethondes on 22 June 1940, Metropolitan France was divided up on 25 June to create two main zones on either side of an arbitrary abstract line that cut across départements, municipalities, fields and woods. The line was to undergo various modifications over time, dictated by the occupying power’s whims and requirements. Starting from the Spanish border near the municipality of Arnéguy in the département of Basses-Pyrénées (present-day Pyrénées-Atlantiques), the demarcation line continued via Mont-de-Marsan, Libourne, Confolens and Loches, making its way to the north of the département of Indre before turning east and crossing Vierzon, Saint-Amand- Montrond, Moulins, Charolles and Dole to end at the Swiss border near the municipality of Gex. The division created a German-occupied northern zone covering just over half the territory and a free zone to the south, commonly referred to as “zone nono” (for “non- occupied”), with Vichy as its “capital”. The Germans kept the entire Atlantic coast for themselves along with the main industrial regions. In addition, by enacting a whole series of measures designed to restrict movement of people, goods and postal traffic between the two zones, they provided themselves with a means of pressure they could exert at will. -

Territoire De Belfort Iiie Inventaire 1995

Inventaire forestier départemental Territoire de Belfort IIIe inventaire 1995 MINISTÈRE DE L'AGRICULTURE, DE L’ALIMENTATION, DE LA PÊCHE ET DES AFFAIRES RURALES INVENTAIRE FORESTIER NATIONAL _________ DÉPARTEMENT DU TERRITOIRE-DE-BELFORT _________ TROISIÈME INVENTAIRE FORESTIER DU DÉPARTEMENT (1995) Résultats et commentaires © IFN 2005 Troisième inventaire PLAN CHAPITRE 1er - GÉNÉRALITÉS 1.1 - Présentation et dates des inventaires page 6 1.2 - Principaux résultats page 7 1.3 - Carte des taux de boisement par région forestière page 9 CHAPITRE 2 - RÉGIONS FORESTIÈRES 2.1 - Carte des régions forestières page 12 2.2 - Cadre géographique page 13 2.3 - Les régions forestières du Territoire-de-Belfort page 15 - Collines sous-vosgiennes sud page 18 - Vosges cristallines page 22 - Jura page 26 - Pays de Belfort page 30 - Sundgau page 34 CHAPITRE 3 - TYPES DE PEUPLEMENT 3.1 - Généralités sur les types de formation végétale page 38 3.2 - Types de peuplement page 39 CHAPITRE 4 - TABLEAUX DE RÉSULTATS STANDARD page 53 CHAPITRE 5 – ÉVOLUTIONS ET COMMENTAIRES 5.1 - Surfaces, volumes et accroissements page 102 5.2 - Principales essences (chênes, hêtre, autres feuillus, épicéa commun et sapin pectiné, autres conifères) page 114 CHAPITRE 6 - ANNEXES 6.1 - Méthode d’inventaire utilisée page 126 6.2 - Précautions à observer dans l’utilisation des résultats page 129 6.3 - Précision des résultats page 132 6.4 - Bibliographie page 133 6.5 - Glossaire page 134 6.6 - Tableau de correspondance publication/carte page 141 …… 3 Territoire de Belfort 4 Inventaire forestier national Troisième inventaire 1 GÉNÉRALITÉS 5 Territoire de Belfort 1.1 PRÉSENTATION ET DATES DES INVENTAIRES Trois inventaires forestiers du département du Territoire-de-Belfort ont été réalisés aux dates suivantes : 1975, 1984 et 1995.