Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard Anthony E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Social Determinants of Unmet Hospitalisation

Nagulapalli, S 2013 Data from “Social determinants of unmet hospitalisation need amongst the poor in Andhra Pradesh, India: A cross-sectional study.” Journal of Open Public Health Data 1(1):e6, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jophd.af DATA PAPER Data from “Social determinants of unmet hospitalisation need amongst the poor in Andhra Pradesh, India: A cross- sectional study.” Srikant Nagulapalli1 2 1 Government of Andhra Pradesh, India 2 Collector and District Magistrate of Nellore, Andhra Pradesh, India The dataset is of a health survey amongst the 21.5 million poor families of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh conducted during April and May 2013. The dataset captures individual characteristics and household characteristics of the past 365 days. Data was collected by 2022 trained field staff of Aarogyasri Health Care Trust (AHCT) of Government of Andhra Pradesh using a questionnaire mod- elled after that used for the health surveys by National Sample Survey Organisation of India. Keywords: health survey of Andhra Pradesh; Rajiv Aarogyasri; unmet hospitalisation need Funding statement The data is not the result of any funded project. (1) Overview (2) Methods Context Steps a) Design of questionnaire: National Sample Survey Spatial coverage Organisation (NSSO), Ministry of Statistics, Government Description: 23 districts Adilabad, Nizamabad, Karimna- of India conducts yearly consumer expenditure surveys as gar, Warangal, Hyderabad, Rangareddy, Medak, Mahbub- well as focussed surveys on health care. The health survey nagar, Nalgonda, Anantapur, Kurnool, Kadapa, Chittoor, questionnaire and the consumer expenditure question- Nellore, Prakasam, Guntur, Krishna, Khammam, West naire used for the 60th round (2004-05) of NSSO were Godavari, East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram integrated by suitably abridging the consumer expendi- and Srikakulam of Andhra Pradesh state, India were cov- ture details and used for this survey. -

The BPL Dilemma

Reprinted with permission from CQ VHF Magazine, Spring 2004 issue. Copyright CQ Communications 2004 The BPL Dilemma Hams claim Broadband over Power Lines will interfere with their on-the-air operations. The utility companies claim not. Read how they are both right . sort of. By Gary Pearce,* KN4AQ still academic. They haven’t encountered Because of the importance of the it yet. I will provide a quick tutorial. Broadband over Power Lines (BPL) The basics of BPL are simple. It is a issue, “FM” columnist Gary Pearce, method of delivering high-speed internet KN4AQ, devotes his space this time to the to homes and small businesses using the investigation of a BPL test site and the local power lines that crisscross neigh- surrounding area. He will be back in the borhoods either overhead or under- next issue of CQ VHF with his regular ground. This is a brilliantly obvious idea column material. —N6CL (“the wires are already there!”) that was delayed because the AC power grid is a really noisy, crappy signal-delivery ince last fall, I’ve been up to my medium for anything above 60 Hz. The eyeballs in BPL—Broadband over march of technology, however, is mak- Power Lines—and its effect on ing it feasible. It is the third method of Samateur radio. If you’re up on current TV doing that, following DSL (Digital culture, you can call it “HF Eye for the FM Subscriber Line) on the phone lines and Guy.” Our area has been “lucky” enough cable TV (nobody’s come up with a cute to host one of the few BPL trials, courtesy name or acronym for broadband over of my local power company, Progress cable TV; they just call it “cable”). -

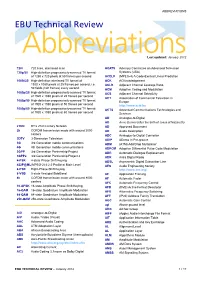

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts Ltd, (September, 23rd) sold 358 rams and females at its annual show and sale sponsored by Norvite. The judges, Mr John & Mr James Scott, Fearn Farm, Tain, awarded the overall show champion and winner of the Mountrich trophy to a Suffolk shearling from Messrs A. Shepherd & Sons, Stonyford Farm, Tarland, which realised £650 and the reserve champion was awarded to a Texel shearling from Messrs D. N. Campbell, Bardnaclaven Farm, Thurso, which realised £700. In the Cheviot section the judge Mr R. MacKenzie, Muirton, Munlochy awarded the N. C. Cheviot Park champion to a shearling from Mr J. S. MacKay, Biggins, Wick, which realised £600. Blue Du Main shearlings (one) sold to £500 from Hern Farm, Errol. Charollais shearlings (7) sold to £320 from Upper Auchenlay, Dunblane. Beltex shearlings (15) sold to £550 twice from The Stables, Fearn & Braes of Coulmore, North Kessock. Suffolk shearlings (63) sold to £850 from North Essie, Adziel. Texel shearlings (119) sold to £1,450 from Clyth Mains, Occumster. Blue Texel shearlings (2) sold to £380 from Greenlands, Arabella. Millenium Blue shearlings (2) sold to £500 from Bardnaheigh, Harpsdale. Blue Faced Leicester shearlings (46) sold to £1,100 from Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord. Dorset Poll shearlings (4) sold to £300 twice from Rheindown Croft, Teandalloch. Cross shearlings (19) sold to £600 from Overhouse, Orkney. Cheviot rams (32) sold to £600 for the champion from Biggins, Wick. Suffolk ram lambs (14) sold to £420 from Easthouse, Orkney. Texel ram lambs (4) sold to £380 twice from Wester Raddery, Fortrose. Blue Faced Leicester ram lambs (one) sold to £420 from Wester Raddery. -

Section 9 Summary of Results 9.1 Introduction 9.2

SECTION 9 SUMMARY OF RESULTS 9.1 INTRODUCTION Section 9.2 summarizes the results of NTIA’s preliminary investigations (Sections 2 – 5). These investigations helped refine the scope and approach of NTIA’s analyses and established certain technical assumptions. Section 9.3 summarizes the results of NTIA’s Phase 1 analyses of interference risks (Section 6), measurement procedures (Section 7) and techniques for prevention and mitigation of interference (Section 8). Section 9.4 summarizes matters requiring further study. 9.2 PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS 9.2.1 Descriptions of BPL Systems NTIA identified three architectures for access BPL networks (Section 2): (1) BPL systems using different frequencies on medium- and low-voltage power lines for networking within a neighborhood and extensions to users’ premises, respectively; (2) BPL use of only medium voltage lines for networking within a neighborhood, with other technologies being used for network extensions to users’ premises; and (3) BPL use of the same frequencies on medium- and low-voltage power lines for networking in a neighborhood and extensions to users’ premises. Responses of BPL manufacturers and operators to the FCC’s BPL NOI generally indicate that BPL systems will operate at or near the Part 15 field strength limits in order to achieve maximum throughput and distance separation between BPL devices. NTIA addressed simple BPL deployment models in the Phase 1 interference risk analyses (Section 6). Specifically, a single BPL device and associated power lines were considered for cases of potential interference to ground-based radio receivers and several co-frequency BPL devices were assumed to be deployed throughout the area covered by an aircraft receiver antenna. -

(November 16Th) Sold 26 Goats, 4 Alpaca, 799 Sheep and 457 Lots of Poultry, Eggs & Poultry Equipment at Their, Rare & Traditional Breeds of Livestock Sale

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts (November 16th) sold 26 goats, 4 alpaca, 799 sheep and 457 lots of poultry, eggs & poultry equipment at their, rare & traditional breeds of livestock sale. Goats (26) sold to £380 for pygmy female with a kidd at foot from Allt A’Bhonich, Stromeferry. Alpaca (4) sold to £550 gross for a pair of males from Meikle Geddes, Nairn. Sheep (799) sold to £1,600 gross for a Valais Blacknose ram from 9 Drumfearn, Isleornsay. Poultry (457) sold to £170 gross for a trio of Mandarin from old Schoolhouse, Balvraid. Sheep other leading prices: Zwartble gimmer: 128 Kinlochbervie, Kinlochbervie, £110. Zwartble in lamb gimmers: Carn Raineach, Applecross, £180. Zwartble ewe: 1 Georgetown Farm, Ballindalloch, £95. Zwartble in lamb ewe: Old School, North Strome, £95 Zwartble ewe lambs: Speylea, Fochabers, £85. Zwartble tup lamb: Old School, £55. Zwartble rams: Wester Raddery, £320. Sheep: Lambs: Valais Blacknose – Scroggie Farm, Dingwall, £500; Dorset – An Cala, Canisby, £200; Ryeland – Stronavaich, Tomintoul, £150; Blue Faced Leicester – Beldhu, Croy, £130; Herdwick – Broombank, Culloden, £110; Border Leicester – Balmenach Farm, Ballater, £105; Kerryhill – Invercharron Mains, Ardgay, £100 (twice); Jacob – Lochnell Home Farm, Benderloch, £100; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, Kinlochewe & Bogburn Farm, Duncanston, £90; Texel – Inverbay, Lower Arboll, £90 (twice); Llanwenog – Burnfield Farm, Rothiemay, £80; Clune Forest – 232 Proncycroy, Dornoch, £74; Blackface – Bogburn Farm, £60; Gotland – Myre Farm, Dallas, £60; Hebridean – Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord, £55; Shetland – Upper Third Croft, Rothienorman, £50.Gimmers: Beltex – Knockinnon, Dunbeath, £300; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, £220; Herdwick – Duror, Glenelg, £170; Dorset – Knockinnon, £155; Ryeland – 5 Terryside, Lairg, £120; Jacob – Killin Farm, Garve, £85; Hebridean – Eagle Brae, Struy, £65; Shetland – Lamington, Oyne, £50; Texel – Sandside Cottage, Tomatin, £50. -

Maccoinnich, A. (2008) Where and How Was Gaelic Written in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scotland? Orthographic Practices and Cultural Identities

MacCoinnich, A. (2008) Where and how was Gaelic written in late medieval and early modern Scotland? Orthographic practices and cultural identities. Scottish Gaelic Studies, XXIV . pp. 309-356. ISSN 0080-8024 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4940/ Deposited on: 13 February 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk WHERE AND HOW WAS GAELIC WRITTEN IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND? ORTHOGRAPHIC PRACTICES AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES This article owes its origins less to the paper by Kathleen Hughes (1980) suggested by this title, than to the interpretation put forward by Professor Derick Thomson (1968: 68; 1994: 100) that the Scots- based orthography used by the scribe of the Book of the Dean of Lismore (c.1514–42) to write his Gaelic was anomalous or an aberration − a view challenged by Professor Donald Meek in his articles ‘Gàidhlig is Gaylick anns na Meadhon Aoisean’ and ‘The Scoto-Gaelic scribes of late medieval Perth-shire’ (Meek 1989a; 1989b). The orthography and script used in the Book of the Dean has been described as ‘Middle Scots’ and ‘secretary’ hand, in sharp contrast to traditional Classical Gaelic spelling and corra-litir (Meek 1989b: 390). Scholarly debate surrounding the nature and extent of traditional Gaelic scribal activity and literacy in Scotland in the late medieval and early modern period (roughly 1400–1700) has flourished in the interim. It is hoped that this article will provide further impetus to the discussion of the nature of the literacy and literary culture of Gaelic Scots by drawing on the work of these scholars, adding to the debate concerning the nature, extent and status of the literacy and literary activity of Gaelic Scots in Scotland during the period c.1400–1700, by considering the patterns of where people were writing Gaelic in Scotland, with an eye to the usage of Scots orthography to write such Gaelic. -

G3/0'4 18909 I

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM (NASA) 91 A MICRO-COMPUTER BASED SYSTEM TO COMPUTE MAGNETIC VARIATION A microcomputer-based implementation of a magnetic variation model for the continental United States is presented. The implementation computes magnetic variation as a function of latitude and longitude for general aviation receivers such as Loran-C. by Rajan Kaul Avionics Engineering Center Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Ohio University Athens, Ohio 45701 March 1984 Prepared for National Aeronautics and Space Administration Langley Research Center Hampton, Virginia 23665 Grant No. NOR 36-009-017 (NASA-CR-1713376) A MICRO-COMPUTER BASED B84-20506 SYSTEM TO COMPUTE MAGNETIC VARIATION (Ohio Univ,) 26 p HC A03/IF A01 CSCL 17G Unclas G3/0'4 18909 I. INTRODUCTION A Mathematical model of magnetic variation in the continental United States (COT48) has been implemented in the Ohio University Loran-C receiv er. The model is based on a least squares fit of a polynomial function. The implementation on the micro-processor based Loran-C receiver is pos sible with the help of a math chip, Am9511 manufactured by Advanced Micro Devices, which performs 32 bit floating point mathematical operations. A Peripheral Interface Adapter (M6520) is used to communicate between the 6502 based micro-computer and the 9511 math chip. The implementation pro vides magnetic variation data to the pilot as a function of latitude and longitude. This report briefly describes the model and the real time implementation in the receiver. II. THE MATHEMATICAL MODEL The model was developed at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) by Fabiano et al. [11, by performing least squares analysis on more than 34,000 data measurements taken between 1900 and 1974. -

Report ITU-R SM.2451-0 (06/2019)

Report ITU-R SM.2451-0 (06/2019) Assessment of impact of wireless power transmission for electric vehicle charging on radiocommunication services SM Series Spectrum management ii Rep. ITU-R SM.2451-0 Foreword The role of the Radiocommunication Sector is to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient and economical use of the radio- frequency spectrum by all radiocommunication services, including satellite services, and carry out studies without limit of frequency range on the basis of which Recommendations are adopted. The regulatory and policy functions of the Radiocommunication Sector are performed by World and Regional Radiocommunication Conferences and Radiocommunication Assemblies supported by Study Groups. Policy on Intellectual Property Right (IPR) ITU-R policy on IPR is described in the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC referenced in Resolution ITU- R 1. Forms to be used for the submission of patent statements and licensing declarations by patent holders are available from http://www.itu.int/ITU-R/go/patents/en where the Guidelines for Implementation of the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC and the ITU-R patent information database can also be found. Series of ITU-R Reports (Also available online at http://www.itu.int/publ/R-REP/en) Series Title BO Satellite delivery BR Recording for production, archival and play-out; film for television BS Broadcasting service (sound) BT Broadcasting service (television) F Fixed service M Mobile, radiodetermination, amateur and related satellite services P Radiowave propagation RA Radio astronomy RS Remote sensing systems S Fixed-satellite service SA Space applications and meteorology SF Frequency sharing and coordination between fixed-satellite and fixed service systems SM Spectrum management Note: This ITU-R Report was approved in English by the Study Group under the procedure detailed in Resolution ITU-R 1. -

Broadband Over Power Lines a Foundation for the Utility of the Future

Broadband over Power Lines a Foundation for the Utility of the Future Jay M. Bradbury Duke Energy Regulatory Manager – Powerline Communications October 26, 2006 LSU Center for Energy Studies – Energy Summit 2006 Topics • BPL Explored a Primer • The Duke Experience • BPL as an Enabler of the Utility of the Future 1 BPL Explored A Primer 2 BPL Defined • Access Broadband Over Power Line (Access BPL). A carrier current system installed and operated on an electric utility service as an unintentional radiator that sends radio frequency energy on frequencies between 1.705 MHz and 80 MHz over medium voltage lines or low voltage lines to provide broadband communications and is located on the supply side of the utility service’s points of interconnection with customer premises. Access BPL does not include power line carrier systems as defined in Section 15.3(t) of this part or In-House BPL systems as defined in Section 15.3(gg) of this part. (FCC) – Electric utility companies can use Access BPL systems to monitor, and thereby more effectively manage, their electric power distribution operations. – Access BPL systems can also deliver high speed Internet and other broadband services to homes and businesses. • In-House Broadband Over Power line (In-House BPL). A carrier current system, operating as an unintentional radiator, that sends radio frequency energy to provide broadband communications on frequencies between 1.705 MHz and 80 MHz over low- voltage electric power lines that are not owned, operated or controlled by an electric service provider. The electric power lines may be aerial (overhead), underground, or inside walls, floors or ceilings of user premises. -

Karen Eastwood Registry Officer

Page 1 of 2 Archived: 16 September 2019 16:23:08 From: [email protected] Sent: 16 September 2019 13:26:01 To: Registry Dingwall Cc: marine. planning@shetland. gov.uk Subject: CAR/L/1185816 - Wick of Gruting Marine Pen Fish Farm, Fetlar, Shetland Importance: Normal Hi Karen, Thanks for this. The corresponding planning application ( Ref: 2019/ 012/ MAR) is currently under determination by Shetland Islands Council. The application was validated on 5th July 2019, and we hope to make a decision within the statutory 4 month period (by/ before 4th November 2019). The application details, and correspondence received to date can be viewed on our website at: https:// pa.shetland. gov.uk/ online-applications/ search. do?action=simple& searchType= Application https:// pa.shetland. gov.uk/ online-applications/ applicationDetails. do? keyVal= PU47YROA02300& activeTab= summary Regards Simon Simon Pallant | Coastal Zone Manager – Marine Planning | Shetland Islands Council | Development Services 8 North Ness Business Park | Lerwick | Shetland | ZE1 0LZ Tel: 01595 744805 From: Registry Dingwall [ mailto: registrydingwall@sepa. org.uk] Sent: 16 September 2019 10:59 To: Marine Planning@Development Services < marine. planning@shetland. gov.uk> Subject: CAR/ L/ 1185816 - Wick of Gruting Marine Pen Fish Farm, Fetlar, Shetland Hi, Please see attached consultation request for an application for CAR/ L/ 1185816. https:// www.sepa.org.uk/ regulations/ consultations/ advertised- applications- under-car/ Thanks Karen Karen Eastwood Registry Officer Dingwall Registry Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Graesser House, Fodderty Way, Dingwall, IV15 9XB tel: 01349 862021 dd: 01349 860384 e-mail: registrydingwall@sepa. org.uk; www.sepa.org.uk The information contained in this response relates to only information held on SEPA’ s Public Register as required by the relevant Legislation.