Current Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

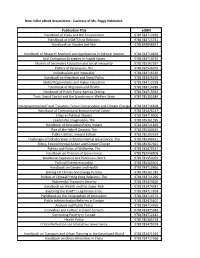

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate by David Andrew Graham A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by David Andrew Graham 2013 The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate David Andrew Graham Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis contributes to the debate over the meaning and function of the doctrine of divine impassibility in theological and especially christological discourse. Seeking to establish the coherence and utility of the paradoxical language characteristic of the received christological tradition (e.g. the impassible Word became passible flesh and suffered impassibly), it argues that the doctrine of divine apatheia illuminates the apocalyptic and soteriological dimension of the incarnate Son’s passible life more effectively than recent reactions against it. The first chapter explores the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and the meaning and place of apatheia within it. In light of the christological tradition which Cyril epitomized, the second chapter engages contemporary critiques and re-appropriations of impassibility, focusing on the particular contributions of Jürgen Moltmann, Robert W. Jenson, Bruce L. McCormack and David Bentley Hart. ii Acknowledgments If this thesis communicates any truth, beauty and goodness, credit belongs to all those who have shaped my life up to this point. In particular, I would like to thank the Toronto School of Theology and Wycliffe College for providing space to do theology from within the catholic church. -

Divine Presence Theology Versus Name Theology in Deuteronomy.”

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 55, No. 1, 3. Copyright © 2017 Andrews University Seminary Studies. RETRACTION FOR PLAGIARISM: ROBERTO OURO, “DIVINE PRESENCE THEOLOGY VERSUS NAME THEOLOGY IN DEUTERONOMY.” The editors of Andrews University Seminary Studies retract the following article by Roberto Ouro because of plagiarism: “Divine Presence Theology versus Name Theology in Deuteronomy” AUSS 52.1 (2014): 5–29. This article is retracted because the author plagiarized substantial portions from another work, misrepresenting the argumentation of the article as original work. This retraction has no bearing on the validity of the sources from which the article draws. 3 Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 52, No. 1., 5-29. Copyright © 2014 Andrews University Press. DIVINE PRESENCE THEOLOGY VERSUS NAME THEOLOGY IN DEUTERONOMY ROBERTO OURO Adventist School of Theology Valencia, Spain Introduction Name Theology has long been understood by biblical scholars to be evidence of a paradigm shift within the Israelite theology of Divine Presence. This paradigm shift involves a supposed evolution in Israelite religion away from the anthropomorphic and immanent images of the deity, as found in Divine Presence Theology, toward a more abstract, demythologized, and transcendent one, as in Name Theology. According to Name Theology, the book of Deuteronomy is identifi ed as the transition point in the shift from the “older and more popular idea” that God lives in the temple with the idea that he is actually only hypostatically present in the temple. This new understanding theologically differentiates between “Jahweh on the one hand and his name on the other.”1 The residual effect of Name Theology is acutely evident in its immanence–to-transcendence scheme. -

A Religion?: Interactions of Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy in Hinduism

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 18 Article 3 2019 What "Makes" a Religion?: Interactions of Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy in Hinduism Eva Rosenthal Denison University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rosenthal, Eva (2019) "What "Makes" a Religion?: Interactions of Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy in Hinduism," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 18 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol18/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Rosenthal: What Makes Religion THE DENISON JOURNAL OF RELIGION What “Makes” a Religion?: Interactions of Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy in Hinduism Eva Rosenthal Abstract This paper explores the complexities of the following question: In being Hindu, in what ways does one “practice” and in what ways does one “believe?” To what extent are ancient texts considered an un-debatable “source” for faith in divine presence? Gaining an understanding of what these texts are and how exactly they relate to both ritual and belief (because, as we will come to find, both ritual and belief are present in every facet of Hindu worship; what we are looking at is their interaction with one another and which seems to be of more importance in each given circumstance) will be instrumental to exploration of the “bigger question.” Those who have grown up within any given religious tradition often grapple with the question of what makes them a “good” Christian, Muslim, Jew, or what- ever their religion might be. -

SYMBOLS, MEANING, and the DIVINE PRESENCE LANGDON GILKEY University of Chicago Divinity School

SYMBOLS, MEANING, AND THE DIVINE PRESENCE LANGDON GILKEY University of Chicago Divinity School YMBOL-MAKING in America is my theme, but inevitably this means for S1 us theological and liturgical symbols in America. More precisely, liturgical symbols in the secular American world, not yet lost for God and yet in vast difficulty with its liturgical symbols. How are theological and liturgical symbols possible in secular America? My central thesis is perhaps better expressed by Raimundo Panikkar: liturgy must express the sacred quality of the secular if it is to be meaningful. I shall here try to follow out the implications of this thesis with regard not only to theology and ethics—as many Catholics have already sought to do—but with regard to liturgy. HOW SYMBOLS MEAN FOR US How do symbols mean for us? And how is it that in meaning for us, symbols seem to put us in touch with what is real and to communicate to us a cohering and transforming power? These are the basic questions both of contemporary theology and of liturgy—the two disciplines, separate as they seem, which live in and through the same mystery of divine communication, of reality and power transmitted through sym bols. In both cases, although we can reflect on this mystery of divine communication, we cannot ourselves create or evoke it, or increase it by rearranging the furniture. The direction of the movement comes the other way: the divine communicates itself to us through symbols, its presence is there already in the symbols, and our worship, like our theological affirmation, is a response to this objective presence—as the classical doctrines of revelation, ex opere operato, justification by grace through faith alone, and Barth's theory of religious language each in its own queer way affirm. -

Christology : a Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHRISTOLOGY : A BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, AND SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF JESUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gerald SJ OCollins | 416 pages | 31 Aug 2009 | Oxford University Press | 9780199557875 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Christology : A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus PDF Book Local Book Search. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Despite the assertion that the resurrection is the interpretive key for Christology pp. This integral Christology is built around the resurrection of the crucified Jesus, highlights love as the key to redemption, and proposes a synthesis of the divine presence through Jesus. Just jnr, Arthur J. Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. Publisher: Oxford University Press. Not many scholars would attempt to provide an overview of biblical, historical, and systematic issues pertaining to Christology. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Bibliografische Informationen. Gerald O'Collins, SJ. To learn more, view our Privacy Policy. I personally would like to develop a Christology from its sources in Jewish and Catholic mysticism taking into account the historical Jewish background as an important element. Original publication date. Final two chapters were excellent and very thought provoking.. McIntosh, Mark A. Buy from amazon. Add comment. Read more What should the feminist movement highlight in presenting Jesus? Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Content protection. Meine Mediathek Hilfe Erweiterte Buchsuche. Want to Read saving…. Audible 0 editions. This book critically examines the best biblical and historical scholarship before tackling head-on some of the key questions of systematic Christology: does orthodox faith present Jesus the man as deficient and depersonalized? You must have a subscription and be logged in to read the entire article. -

The Sacredness of the Universe in the Hindu Scriptures

Ephemerides Carmeliticae 26 (1975/1) 213-229 THE SACREDNESS OF THE UNIVERSE IN THE HINDU SCRIPTURES « If I were to ask myself, from what literature we here in Eu rope, — we who have been nurtured almost exclusively on the thoughts of the Greeks and the Romans and the one Semitic race, the Jewish ■— may draw that corrective which is most wanted in order to make our inner life more perfect, more comprehensive, more universal, in fact, more truely human, a life, not for this life alone but a transfigured and eternal life, again I should point to India »*. This high eulogy showered on the sacred scriptures of the Hindus by the famous Orientalist, Prof. Max Müller, gives a good start to our study which seeks to bring into relief the sacredness of the universe as envisaged in those scriptures. — As is well known, Hinduism is extremely rich in sacred scriptu res. They come under two categories: Sruti (revelation) and Smrti (tradition). Sruti which literally means 'what is heard’ is consi dered to be a deposit of eternal, infallible truths experienced or ' heard ’ by the holy sages of old in their moments of spiritual illu mination. Those sages are not regarded as their authors, but only as manifesters of the eternal truths which exist by themselves as « väk» (verbum, logos). Smrti, on the other hand, which etymolo- gically means ' recollection ’ includes all the rest of the religious li terature, which are authoritative only in so far as they are in confor mity with the Sruti. Here we intend to make a rapid survey of two important sections of Sruti, namely the Rgveda Samhita and the principal Upanisads; while- from the Smrti we shall take into con sideration the Bhagvadglta (or Gita) and the Dharmasästras (the Law Books). -

Pre-Nestorianism” in Spain: the Letter of Vitalis and Constantius and Pseudo-Athanasian De Trinitate

Junghoo Kwon Dream School Seosan, S. Korea [email protected] “PRE-NESTORIANISM” IN SPAIN: THE LETTER OF VITALIS AND CONSTANTIUS AND PSEUDO-ATHANASIAN DE TRINITATE Leporius from Gaul has been regarded as a precursor to Nestorius in the West.1 At the same time, he has been found to be the only fi gure tied with “pre-Nestorianism” in the West. In this paper, I would like to introduce two more “pre-Nestorian” examples which deserve our att ention: The Lett er of Vitalis and Constantius (ca. 431)2 and the pseudo- Athanasian De trinitate.3 Both documents came from Spain and most likely they were writt en in the early part of the fi fth century. These Spanish documents present an extremely strong dyphysite Christol- ogy in danger of proposing two independent entities in the Media- tor. First, I will point out key Christological points of each document (parts 1 and 2). Then, I will demonstrate the critical reaction to such acute two-natured Christology on the part of Capreolus, the bishop of Carthage (part 3). Finally, I will argue that one of the major factors that produced the theological context for such a strong dyphysite Christol- ogy was that of the Latin Arians (part 4). (1) A. GRILLMEIER, Christ in Christian Tradition, vol. 1, Atlanta, 1975, pp. 464–467. (2) PL 53, 847–849. The Latin text is also available in P. GLORIEUX, Pré Ne- storianisme en Occident, Rome, 1959, pp. 39–41. (3) PL 62, 237–334; CCSL 9:3–99. For a comprehensive overview of the previous studies on the pseudo-Athanasian De Trinitate including the questions of authorship, date and place of origin, see the doctoral thesis of J. -

Levels of Existence in Islamic Mysticism and Buddhist Mahayana

Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 4, Issue 1, 2020, PP 8-18 ISSN 2637-5907 Levels of Existence in Islamic Mysticism and Buddhist Mahayana Ali reza Khajegir*, Sarvnaz Heidary PhD (Comparative religions and Mysticism) Shahrekord university, MA in religions and comparative mysticism, Shahrekord university Iran. *Corresponding Author: Ali reza Khajegir, PhD (Comparative religions and Mysticism) Shahrekord university, Iran. E-mail:[email protected]. ABSTRACT In the comparative studies of religions and mystical schools various, terms are used which despite linguistic differences, can refer to a single truth and have many similarities. The concepts of the Buddhist trikaya and the five divine presence in Islamic mysticism are among these reforms. In most of the mystical schools, in the form of generalization of universes, there is a discussion of the mystical worldview. In these two schools. For the comparative study of cosmology, it is necessary to explain the manifestation of transcendental truth. In this regard, the two concepts of the five divine presence and the trikaya, one of Islamic mysticism and Buddhism of Mahayana, the transcendental truth, have been discussed, and the aspects if the sharing and differences of these levels of existence have been investigated. In terms of school of Mahayana .almightiness, divinity and absoluteness, they are bodhisattva, dharmakaya and nirvana. Both schools believe that the single truth for it’s appearance and presence in the material world has its own manifestation. Although this transcendental nature is mentioned by a different name, it is nonetheless referred to as a single entity. Keywords: Trikaya, The five divine presence, Transcendental essence, universe levels, Mahayana INTRODUCTION the general aspects of the universe and manifestations of the emergence of truth. -

The Presence of Christ in the Eucharist: a Strange Neglect of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Mary Immaculate Research Repository and Digital Archive The Presence of Christ in the Eucharist: A Strange Neglect of the Resurrection? Research Masters in Theology Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick David Kennedy Student Number: 13172921 Supervisor: Rev. Dr. Eugene Duffy Abstract The Presence of Christ in the Eucharist: A Strange Neglect of the Resurrection? Eminent theologians, Gerald O’Collins, Anthony J. Kelly and Luis M. Bermejo claim that a strange neglect of Jesus’ resurrection persists in contemporary theologies of the Eucharist. All three suggest that this deficiency emerges from, and is most evident in, theologies of the Eucharist which are shaped by the insights of classical Christology. This thesis will demonstrate that the narrowness and rigidity of such Christology with regard to the Eucharist, finds its clearest expression in the neo-scholastic manualist tradition. To show how traditional theologians failed to engage with Jesus’ resurrection Joseph Pohle’s dogmatic treatise on the Eucharist first published in 1917, is presented herein. However, while such traditional discourse on the Eucharist prevailed in the seminaries in the early twentieth century, a clear shift soon began to emerge, whereby sacramental theologians on mainland Europe broke away from the narrow approach of neo-scholastic reflection by rediscovering the centrality of the Paschal Mystery to theologies of the Eucharist. This thesis suggests that the break with the neo-scholastic manualist tradition and its treatment of the Eucharist, finds its origins in the writings of the Benedictine liturgist, Dom Odo Casel, whose treatise on the mystery of Christian Worship was published in 1932. -

The Spirit's Presence and Activity in Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-21-2021 Jesus In, With, And Under the Spirit: The Spirit's Presence and Activity in Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar Brian A. Gauthier [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/phd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Gauthier, Brian A., "Jesus In, With, And Under the Spirit: The Spirit's Presence and Activity in Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar" (2021). Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. 92. https://scholar.csl.edu/phd/92 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JESUS IN, WITH, AND UNDER THE SPIRIT: THE SPIRIT’S PRESENCE AND ACTIVITY IN CHRIST IN THE SACRAMENT OF THE ALTAR A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Systematic Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Brian Andrew Gauthier April, 2021 Approved by: Dr. Leopoldo A. Sánchez M. Dissertation Advisor Dr. David R. Maxwell Reader Dr. Bruce G. Schuchard Reader © 2021 by Brian Andrew Gauthier. All rights reserved. ii I dedicate this work to my beloved bride, Amanda, and my beautiful children, Ezra Joel and Aviva Eliana. -

The Practice of the Presence of God: the Best Rule of Holy Brother Lawrence Life

The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Brother Lawrence Life Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Life. p. 1 Preface. p. 2 Conversations. p. 3 First Conversation. p. 3 Second Conversation. p. 4 Third Conversation. p. 6 Fourth Conversation. p. 7 Letters. p. 10 First Letter. p. 10 Second Letter. p. 11 Third Letter. p. 13 Fourth Letter. p. 13 Fifth Letter. p. 15 Sixth Letter. p. 15 Seventh Letter. p. 16 Eighth Letter. p. 17 Ninth Letter. p. 17 Tenth Letter. p. 18 Eleventh Letter. p. 19 Twelfth Letter. p. 20 Thirteenth Letter. p. 20 Fourteenth Letter. p. 21 Fifteenth Letter. p. 22 Appendix to electronic edition. p. 23 Indexes. p. 24 Index of Scripture References. p. 24 iii The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Brother Lawrence Life iv The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Brother Lawrence Life The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Life being Conversations and Letters of Brother Lawrence Good when He gives, supremely good; Nor less when He denies: Afflictions, from His sovereign hand, Are blessings in disguise. AUTHENTIC EDITION LONDON THE EPWORTH PRESS (Edgar C Barton) 25-35 City Road, E.C.1 The Practice of the Presence of God: The Best Rule of Holy Brother Lawrence Life PREFACE ªI believe in the ... communion of saints.º SURELY if additional proof of its reality were needed, it might be found in the universal oneness of experimental Christianity in all ages and in all lands.