The Sacredness of the Universe in the Hindu Scriptures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God Gave Adam and Eve a New Son, Seth. Genesis 4:25

God gave Adam and Eve a new son, Seth. Genesis 4:25 © GCP www.gcp.org Genesis 4 35 OK to photocopy for church and home use God gave Adam and Eve a new son, Seth. Genesis 4:25 Let’s Talk ASK Adam and Eve sinned against God. But God made a promise to take care of their sin. What did God promise? SAY He promised to send a Savior. God had a wonderful plan to send someone many years later from Eve’s family line who would pay for Adam and Eve’s sin and the sin of all God’s people. SAY First, God gave Adam and Eve two sons, Cain and Abel. Abel trusted God, but Cain did not. Cain killed Abel. ASK Some time later, God gave Adam and Eve a new son. What was his name? SAY God gave Adam and Eve a new son named Seth. Many years later, Jesus, God’s promised Savior, was born into Seth’s family line. God always keeps his promises! Let’s Sing and Do ac Bring several baby blankets or towels to class. Give each child a blanket. Do tr k Preschool these motions as you sing to the tune Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush. 46 Vol. 2 CD 1 God made a promise to Adam and Eve, 2 Adam and Eve had baby Seth, Adam and Eve, Adam and Eve. Baby Seth, baby Seth. God made a promise to Adam and Eve— Adam and Eve had baby Seth— He promised to send a Savior! God would keep his promise! (wave blanket overhead, like a praise banner) (spread blanket, lay picture on it) 3 Through Seth’s family, Jesus came, 4 We believe God’s promises, Jesus came, Jesus came. -

Eve's Answer to the Serpent: an Alternative Paradigm for Sin and Some Implications in Theology

Calvin Theological Journal 33 (1998) : 399-420 Copyright © 1980 by Calvin Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. Scholia et Homiletica Eve's Answer to the Serpent: An Alternative Paradigm for Sin and Some Implications in Theology P. Wayne Townsend The woman said to the serpent, "We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden, but God did say, `You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die. "' (Gen. 3:2-3) Can we take these italicized words seriously, or must we dismiss them as the hasty additions of Eve's overactive imagination? Did God say or mean this when he instructed Adam in Genesis 2:16-17? I suggest that, not only did Eve speak accu- rately and insightfully in responding to the serpent but that her words hold a key to reevaluating the doctrine of original sin and especially the puzzles of alien guilt and the imputation of sin. In this article, I seek to reignite discussion on these top- ics by suggesting an alternative paradigm for discussing the doctrine of original sin and by applying that paradigm in a preliminary manner to various themes in the- ology, biblical interpretation, and Christian living. I seek not so much to answer questions as to evoke new ones that will jar us into a more productive path of the- ological explanation. I suggest that Eve's words indicate that the Bible structures the ideas that we recognize as original sin around the concept of uncleanness. -

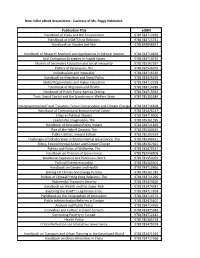

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate by David Andrew Graham A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by David Andrew Graham 2013 The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate David Andrew Graham Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis contributes to the debate over the meaning and function of the doctrine of divine impassibility in theological and especially christological discourse. Seeking to establish the coherence and utility of the paradoxical language characteristic of the received christological tradition (e.g. the impassible Word became passible flesh and suffered impassibly), it argues that the doctrine of divine apatheia illuminates the apocalyptic and soteriological dimension of the incarnate Son’s passible life more effectively than recent reactions against it. The first chapter explores the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and the meaning and place of apatheia within it. In light of the christological tradition which Cyril epitomized, the second chapter engages contemporary critiques and re-appropriations of impassibility, focusing on the particular contributions of Jürgen Moltmann, Robert W. Jenson, Bruce L. McCormack and David Bentley Hart. ii Acknowledgments If this thesis communicates any truth, beauty and goodness, credit belongs to all those who have shaped my life up to this point. In particular, I would like to thank the Toronto School of Theology and Wycliffe College for providing space to do theology from within the catholic church. -

How Can Original Sin Be Inherited?

DEAR FATHER KERPER Michelangelo, The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden. Web Gallery of Art sinned against obedience. But this act How can original represents much more: they actually rejected friendship with God and, even worse, attempted to supplant God as God. sin be inherited? To see this more clearly, we must rewind the Genesis tape back to chapter ear Father Kerper: I’ve always had a huge 1. Here we find that God had created problem with original sin. It seems so unfair. I can the first human beings “in the image of God.” (Genesis 1:27) As such, they understand punishing someone who has broken a immediately enjoyed friendship and law. That’s perfectly just. But why should someone even kinship with God, who had Dwho’s done nothing wrong get punished for what someone else lovingly created them so that they could share everything with Him. did millions of years ago? Though Adam and Eve had everything that human beings could Many people share your understandable In the case of speeding, the possibly enjoy, the serpent tempted reaction against the doctrine of original punishment – say a $200 ticket – is them to seek even more. Recall the sin. As you’ve expressed so well, it does always imposed directly on the specific serpent’s words to Eve: “God knows in indeed seem to violate the basic norms of person who committed an isolated fact that the day you eat it [the forbidden fairness. But it really doesn’t. How so? illegal act. Moreover, the punishment is fruit] your eyes will be opened and you To overcome this charge of unfairness, designed to prevent dangerous and illegal will be like gods.” (Genesis 3:5) we must do two things: first, reconsider behavior by creating terribly unpleasant By eating the forbidden fruit, Adam the meaning of punishment; and second, consequences, namely costly fines and and Eve attempted to seize equality rediscover the social nature – and social eventually the loss of one’s license. -

God Made Eve and Ordained Marriage

GGOODD MMAADDEE EEVVEE aanndd oorrddaaiinneedd mmaarrrriiaaggee Several thousand years have passed since Adam and Eve became man and wife, but God hasn’t changed what he first instructed mankind regarding marriage in the Bible. Did you know that God was the One who decided that man and woman should marry? In Genesis 2 we find part of the wedding service spoken in many wedding ceremonies today. Men and women and marriage and children are very important to God. Marriage is not just a good idea… it’s a “God Idea”! But some people don’t know or don’t believe what God says about marriage. They say that marriage is something to be tried out to see if it will work—depending upon how you feel about it. Many folks are even suggesting that the idea of marriage is outdated. But what does the Bible say about marriage? Let’s take a look and find out! God decided that Adam needed a wife to help him and to be his companion. Genesis 2:18 The LORD God said, “It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him.” God decided that Adam should not live alone. - God was his Creator and knew what was best for him. - God didn’t ask Adam what he wanted or thought best. - God made the decision to make a wife for Adam. God loved Adam and wanted him to be complete. - God knew that Adam wouldn’t continue to be happy if he remained alone. - Because God loved Adam and wanted what was best for him, he decided to make a wife for him. -

Another Look at Cain: from a Narrative Perspective

신학논단 제102집 (2020. 12. 31): 241-263 https://doi.org/10.17301/tf.2020.12.102.241 Another Look at Cain: From a Narrative Perspective Wm. J McKinstry IV, MATS Adjunct Faculty, Department of General Education Presbyterian University and Theological Seminary In the Hebrew primeval histories names often carry significant weight. Much etymological rigour has been exercised in determining many of the names within the Bible. Some of the meaning of these names appear to have a consensus among scholars; among others there is less consensus and more contention. Numerous proposals have come forward with varying degrees of convincing (or unconvincing as the case may be) philological arguments, analysis of wordplays, possi- ble textual emendations, undiscovered etymologies from cognates in other languages, or onomastic studies detailing newly discovered names of similarity found in other ancient Semitic languages. Through these robust studies, when applicable, we can ascertain the meanings of names that may help to unveil certain themes or actions of a character within a narrative. For most of the names within the primeval histories of Genesis, the 242 신학논단 제102집(2020) meaning of a name is only one feature. For some names there is an en- compassing feature set: wordplay, character trait and/or character role, and foreshadowing. Three of the four members in the first family in Genesis, Adam, Eve, and Abel, have names that readily feature all the elements listed above. Cain, however, has rather been an exception in this area, further adding to Genesis 4’s enigmaticness in the Hebrew Bible’s primeval history. While three characters (Adam, Eve, and Abel) have names that (1) sound like other Hebrew words, that are (2) sug- gestive of their character or actions and (3) foreshadow or suggest fu- ture events about those characters, the meaning of Cain’s name does not render itself so explicitly to his character or his role in the narrative, at least not to the same degree of immediate conspicuousness. -

PROGRAM NOTES the Classical Master Josef Haydn and The

Program Notes The Classical master Josef Haydn and the idiosyncratic minimalist Arvo Pärt may seem like a musical odd couple, but this afternoon’s pairing brings to- gether two composers who share some fundamental characteristics. Both are men of a deep personal faith which is often reflected in their music. And both were unafraid to reference contemporary events in their music. Haydn’s title Missa in Tempore Belli (Mass in a Time of War) was his own, and refers to the Napoleonic wars, which were played out in large measure on Austrian soil. Pärt dedicated his 2008 Symphony No. 4 “Los Angeles” to Mikhail Khodoro- vsky, the Russian oil magnate, philanthropist, and vocal critic of the Putin government, whose imprisonment was widely thought to be politically mo- tivated, and his selection of the text for Adam’s Lament is his response to the ongoing tensions between Islamic and Christian worlds. Estonian-born Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) reinvented his compositional style after making an early name for himself as an avant garde composer. His early com- positions were fiercely atonal and serial, but he also experimented with aleatoric music, where he might indicate the range of pitches for a given voice but not specify discrete pitches, rhythms or durations, and collage music, in which he layered phrases of music from composers like Bach onto his own 12- tone music. The premiere of Pärt’s 1968 Credo, a choral collage piece, caused something of an uproar. The use of the liturgical text had not been approved by the Soviet composers’ union and the work was subsequently banned in the Soviet Union. -

EVE E-50Z User Manual Rev

User Manual EVE E-50Z 1. Before You Begin ....................................................................... 1 What Is Included ........................................................................................... 1 Unpacking Instructions.................................................................................. 1 Claims ............................................................................................................................ 1 Text Conventions .......................................................................................... 1 Symbols ........................................................................................................ 1 Disclaimer ..................................................................................................... 1 Product at a Glance ...................................................................................... 2 Safety Notes.................................................................................................. 2 2. Introduction ................................................................................ 3 Product Overview.......................................................................................... 3 Product Dimensions...................................................................................... 4 3. Setup ........................................................................................... 5 AC Power...................................................................................................... 5 -

January 2014 Ensign

OLD TESTAMENT PROPHETS ADAM “Few persons in all eternity have been more directly involved in the plan of salvation . than the man Adam.” 1 ost people know me as the first Because we chose to eat the fruit, God knew that the Fall would Mman to live on the earth, but we had to leave the garden and God’s happen—He sent Jesus Christ to many don’t know that I had a special presence. This is known as the Fall. atone for our sins and overcome responsibility before I came to the We became mortal, experienced both death so that we and our children earth. In the premortal existence, I led the good and the bad of life, and could return to Him.11 God’s armies against Satan’s armies brought children to in the War in Heaven,2 and I helped earth.10 Jesus Christ create the earth.3 I was known as Michael then, which means one “who is like God.” 4 God chose me to be the first man on the earth and placed me in the Garden of Eden, a paradise with many types of plants and ani- mals. He breathed into me “the breath of life” 5 and gave me a new name: Adam.6 God told my wife, Eve, and me not to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.7 If we didn’t eat the fruit, we could stay in the garden and live forever, but we wouldn’t be able to “progress by experiencing opposition in mortality” 8 or have children.9 The choice was ours to make. -

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON GENESIS 4:1–2 Why Did Cain Kill His Brother Abel?

CHAPTER ONE LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON GENESIS 4:1–2 You two are book-men: can you tell me by your wit; What was a month old at Cain’s birth, that’s not five weeks old as yet? (Shakespeare—Love’s Labor’s Lost 4.2.40) Why did Cain kill his brother Abel? It is usually assumed by modern commentators that God’s rejection of Cain’s offering led him to kill his brother in a fit of jealousy.1 Such a conclusion is logical in light of the way the action in the story is arranged. But the fact is we are never told the specific reason for the murder. Ancient exegetes, as we will see later, also speculated over Cain’s motive and sometimes provided the same conclusion as modern interpreters. But some suggested that there was something more sinister behind the killing, that there was something inborn about Cain that led him to earn the title of first murderer. These interpreters pushed back past the actual murder to look, as would a good biographer, at what it was about Cain’s birth and childhood that led him to his moment of infamy. Correspond- ingly, they asked similar questions about Abel. The result was a devel- opment of traditions that became associated with the brothers’ births, names and occupations. Who was Cain’s father? As we noted in the introduction, Cain and Abel is a story of firsts. In Gen 4:1 we find the first ever account of sexual relations between humans with the end result being the first pregnancy. -

![9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9536/9-the-mystical-bitter-water-trial-text-deleted-969536.webp)

9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]

9 The Mystical Bitter Water Trial [text deleted] 9.1 Golems as Archetypes of the Trial’s Supernaturally Inseminated Seed [text deleted] 9.2 Lilith as the First Sotah [text deleted] 9.3 Lilith and Samael as Animating Forces in Golems [text deleted] 9.4 Azazel as the Seed of Lilith No study of Lilith would be complete without a discussion of the demon Azazel. This is true because several clues in many ancient texts - including the Torah, the Zohar, and the First Book of Enoch - indicate that Azazel was the seed of Lilith. The texts further hint that Azazel was not the product of Lilith mating with any ordinary man, but rather he was the firstborn seed resulting from her illicit mating with Semjaza, the leader of a group of fallen angels called Watchers. As the seed of the Watchers, Azazel was the first born of the Nephilim, a race of powerful angel-man hybrids who nearly pushed ordinary mankind to extinction before the flood. But Azazel was much more than just a powerful Nephilim. Regular Nephilim were the products of the daughters of Adam mating with Watchers. Azazel was the product of Lilith mating with the Watchers. He is thus less human than all, and the most powerful, even more powerful than the Watchers who sired him. Azazel’s role in the Yom Kippur ceremony of Leviticus 16 indicates he is a rival to Messiah and God. This identifies Azazel as the legendary seed of the Serpent of Eden. God declared in his curse against the Serpent that this great seed would bruise the heel of Eve’s promised seed (Messiah), but Eve’s seed in turn would crush the head of the Serpent Lilith and destroy her seed.