The Postmodern Spirit and the Status of God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journey to Other Worlds – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri Page 1 of 5

A Journey to Other Worlds – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri Page 1 of 5 University of Missouri A Journal of Undergraduate Writing A Journey to Other Worlds Daniel Miller Daniel Miller graduated from MU with a bachelor of English in May 2014, and he is a first-year masters’ student now in English at MU. His fiction has appeared in ZONE 3, Puerto del Sol, and Hobart, among other publications. He selected to write about this topic simply because he has always been fascinated with astral projection and lucid dreaming. He tried to achieve this state while researching and writing the paper. The astral body appears in many different cultures throughout time and throughout the world. In Egypt, the “KA was not the soul of man . but its vehicle” (Muldoon & Carrington, 2011, p. xxii). In the Qur’an, Muhammad’s astral body travels in the Isra and Mi’raj story. And, among other sacred and secular texts, the astral body appears in Hindu scripture, Taoist practice, and even Christianity. In his article regarding the afterlife, Woolger (2014) notes that “in such journeys in the world religions and innumerable tribal practices” scholars have “described a common pattern of ‘ascent’, which is to say an ecstatic, mystical or out-of body experience, wherein the spiritual traveler leaves the physical body and travels in his/her subtle body into ‘higher’ realms” (para. 4). Dually, this quotation makes apparent the historical depth of astral projection as well as uses specific terms—spiritual, mystical, and the idea of ‘higher’ realms—that separates astral projection from other types of out-of body experiences (OBEs). -

Kant's Theoretical Conception Of

KANT’S THEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF GOD Yaron Noam Hoffer Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy, September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________________ Allen W. Wood, Ph.D. (Chair) _________________________________________ Sandra L. Shapshay, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Timothy O'Connor, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Michel Chaouli, Ph.D 15 September, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Yaron Noam Hoffer iii To Mor, who let me make her ends mine and made my ends hers iv Acknowledgments God has never been an important part of my life, growing up in a secular environment. Ironically, only through Kant, the ‘all-destroyer’ of rational theology and champion of enlightenment, I developed an interest in God. I was drawn to Kant’s philosophy since the beginning of my undergraduate studies, thinking that he got something right in many topics, or at least introduced fruitful ways of dealing with them. Early in my Graduate studies I was struck by Kant’s moral argument justifying belief in God’s existence. While I can’t say I was convinced, it somehow resonated with my cautious but inextricable optimism. My appreciation for this argument led me to have a closer look at Kant’s discussion of rational theology and especially his pre-critical writings. From there it was a short step to rediscover early modern metaphysics in general and embark upon the current project. This journey could not have been completed without the intellectual, emotional, and material support I was very fortunate to receive from my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. -

Automatic Writing and the Book of Mormon: an Update

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTOMATIC WRITING AND THE BOOK OF MORMON: AN UPDATE Brian C. Hales At a Church conference in 1831, Hyrum Smith invited his brother to explain how the Book of Mormon originated. Joseph declined, saying: “It was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.”1 His pat answer—which he repeated on several occasions—was simply that it came “by the gift and power of God.”2 Attributing the Book of Mormon’s origin to supernatural forces has worked well for Joseph Smith’s believers, then as well as now, but not so well for critics who seem certain natural abilities were responsible. For over 180 years, several secular theories have been advanced as explanations.3 The more popular hypotheses include plagiarism (of the Solomon Spaulding manuscript),4 collaboration (with Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, etc.),5 1. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 23. 2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” in Journals, Volume. 1: 1832–1839, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 89; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 5, Mar. 1, 1842, 707. 3. See Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies 58, no. -

Adyar Pamphlets Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits No. 144 Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits by H.P

Adyar Pamphlets Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits No. 144 Theories About Reincarnation and Spirits by H.P. Blavatsky From The Path, November, 1886 Published in 1930 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India OVER and over again the abstruse and mooted question of Rebirth or Reincarnation has crept out during the first ten years of the Theosophical Society's existence. It has been alleged on prima facie evidence, that a notable discrepancy was found between statements made in Isis Unveiled, Volume I, pp. 351-2, and later teachings from the same pen and under the inspiration of the same Master.[ See charge and answer, in Theosophist. August 1882] In Isis it was held, reincarnation is denied. An occasional return, only of “depraved spirits" is allowed. ' Exclusive of that rare and doubtful possibility, Isis allows only three cases - abortion, very early death, and idiocy - in which reincarnation on this earth occurs." (“C. C. M." in Light, 1882.) The charge was answered then and there as every one who will turn to the Theosophist of August, 1882, can see for himself. Nevertheless, the answer either failed to satisfy some readers or passed unnoticed. Leaving aside the strangeness of the assertion that reincarnation - i.e., the serial and periodical rebirth of every individual monad from pralaya to pralaya - [The cycle of existence during the manvantara - period before and after the beginning and completion of which every such "Monad" is absorbed and reabsorbed in the ONE -

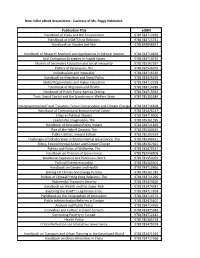

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

ABORIGINAL BELIEFS and REINCARNATION Marjorie Crawley

ABORIGINAL BELIEFS AND REINCARNATION Marjorie Crawley Although reincarnation has been believed over thousands of years among a variety of widely dispersed cultures, apart from the Celtic heritage of many Europeans it is not a concept that is part of our European Australian understanding of the nature of man and his relation- ship to the world. In recent years, however, with the intrusion of Eastern religions, we have been given more opportunity to attempt to understand, if not accept, categories of thought foreign to our own, yet difficulties in understanding the concept of reincarnation persist. For it has been expressed in doctrines that have changed according to the understanding of wisdom, and the needs of the people during the passing ages, even within the same religious tradition. There is also doubt as to whether it was correct to attribute reincarnation beliefs to some cultures, pointing to an indescision as to what counts as evidence and how to interpret it. 1 It is not surprising therefore, to find conflict of opinion as to whether the Aranda believe in reincarnation. Early this century, Baldwin Spencer and F.J. Gillen were cited for the affirmative, and Carl Strehlow for the negative. 2 More recently, T.G.H. Strehlow supported the view, The father of the young initiate then takes the hand of his son, leads him to the cluster, and places the smooth round stone into his hands. Having obtained permission of the other old men present, he tells his son: 'This is your own body from which you have been reborn. It is the true body of the great Tjenterama, the chief of the Ilbalintja storehouse .. -

Synchronicity

Newsletter—June 2015 Synchronicity person's life as dreams – shifting a person's ego- When I began my research on “Synchronicity,” I centric conscious thinking to greater wholeness, was surprised to learn that the concept had been or holistic thinking. From a religious perspec- created by the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, tive, synchronicity is similar to the concept of Carl Jung. As he described it, “Events are Grace, or the “intervention of Grace.” 'meaningful coincidences' if they occur with no When you experience a synchronicity in apparent causal relationship, yet seem to be your life, it reminds you that you are part of a meaningfully related.” At different times, he greater Whole, that the Universe is governed by defined it as “an acausal connecting principle,” laws of Cause and Effect that go outside the “meaningful coincidence,” and “acausal parallel- boundaries of time, space and matter. Synchro- ism.” nicities remind us that Grace can intervene in If you haven't yet read last month's our lives, and, according to the principles of Newsletter, now would be a good time to do so. quantum physics, the more we believe synchro- In it I used as an example of Creation (our theme nicities are possible, the more likely they will last month) the spontaneous manifestation of a occur. missing jewel. That illustration will also serve June is the traditional month for wed- for “Synchronicity” as well, for it occurred as I dings. Let it be your month for your marriage to was writing about creating and manifesting. Grace. Let Divine Intervention be your new Jung developed his concept of Synchro- partner in life, and let no man put that partner- nicity, or acausal connection, after (or during) ship asunder. -

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate by David Andrew Graham A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by David Andrew Graham 2013 The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate David Andrew Graham Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis contributes to the debate over the meaning and function of the doctrine of divine impassibility in theological and especially christological discourse. Seeking to establish the coherence and utility of the paradoxical language characteristic of the received christological tradition (e.g. the impassible Word became passible flesh and suffered impassibly), it argues that the doctrine of divine apatheia illuminates the apocalyptic and soteriological dimension of the incarnate Son’s passible life more effectively than recent reactions against it. The first chapter explores the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and the meaning and place of apatheia within it. In light of the christological tradition which Cyril epitomized, the second chapter engages contemporary critiques and re-appropriations of impassibility, focusing on the particular contributions of Jürgen Moltmann, Robert W. Jenson, Bruce L. McCormack and David Bentley Hart. ii Acknowledgments If this thesis communicates any truth, beauty and goodness, credit belongs to all those who have shaped my life up to this point. In particular, I would like to thank the Toronto School of Theology and Wycliffe College for providing space to do theology from within the catholic church. -

Process Theology 1 Process Theology

Process theology 1 Process theology Process theology is a school of thought influenced by the metaphysical process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) and further developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000). While there are process theologies that are similar, but unrelated to the work of Whitehead (such as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin) the term is generally applied to the Whiteheadian/Hartshornean school. Process theology is unrelated to the Process Church. History The original ideas of process thought are found in the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Various theological and philosophical aspects have been expanded and developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000), John B. Cobb, Jr., and David Ray Griffin. A characteristic of process theology each of these thinkers shared was a rejection of metaphysics that privilege "being" over "becoming," particularly those of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. Hartshorne was deeply influenced by French philosopher Jules Lequier and by Swiss philosopher Charles Secrétan who were probably the first ones to claim that in God liberty of becoming is above his substantiality. Process theology soon influenced a number of Jewish theologians including Rabbis Max Kadushin, Milton Steinberg and Levi A. Olan, Harry Slominsky and, to a lesser degree, Abraham Joshua Heschel. Today some rabbis who advocate some form of process theology include Bradley Shavit Artson, Lawrence A. Englander, William E. Kaufman, Harold Kushner, Anton Laytner, Michael Lerner, Gilbert S. Rosenthal, Lawrence Troster, Donald B. Rossoff, Burton Mindick, and Nahum Ward. Alan Anderson and Deb Whitehouse have attempted to integrate process theology with the New Thought variant of Christianity. The work of Richard Stadelmann has been to preserve the uniqueness of Jesus in process theology. -

Theology Today

Theology Today volume 67, N u m b e r 2 j u l y 2 0 1 0 EDITORIAL Christmas in July 123 JAMES F. KAY ARTICLES American Scriptures 127 C. CLIFTON BLACK Christian Spirituality in a Time of Ecological Awareness 169 KATHLEEN FISCHER The “New Monasticism” as Ancient-Future Belonging 182 PHILIP HARROLD Sexuality as Sacrament: An Evangelical Reads Andrew Greeley 194 ANTHONY L. BLAIR THEOLOGICAL TABLE TALK The Difference Calvin Made 205 R. BRUCE DOUGLASS CRITIC’S CORNER Thinking beyond Easy Tribalism 216 WALTER BRUEGGEMANN BOOK REVIEWS The Ten Commandments, by Patrick Miller 220 STANLEY HAUERWAS An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts, by D. C. Parker 224 SHANE BERG TT-67-2-pages.indb 1 4/21/10 12:45 PM Incarnation: The Person and Life of Christ by Thomas F. Torrance, edited by Robert T. Walker 225 PAUL D. MOLNAR Religion after Postmodernism: Retheorizing Myth and Literature by Victor E. Taylor 231 TOM BEAUDOIN Practical Theology: An Introduction, by Richard R. Osmer 234 JOYCE ANN MERCER Boundless Faith: The Global Outreach of American Churches by Robert Wuthnow 241 RICHARD FOX YOUNG The Hand and the Road: The Life and Times of John A. Mackay by John Mackay Metzger 244 JOHN H. SINCLAIR The Child in the Bible, Marcia J. Bunge, general editor; Terence E. Fretheim and Beverly Roberts Gaventa, coeditors 248 KAREN-MARIE YUST TT-67-2-pages.indb 2 4/21/10 12:45 PM James F. Kay, Editor Gordon S. Mikoski, Reviews Editor Blair D. Bertrand, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL COUNCIL Iain R. -

Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim‐

JOURNAL for the SCIENTIFIC STUDY of RELIGION Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim-Majority Countries: Reconceptualization and Assessment MANSOOR MOADDEL STUART A. KARABENICK Department of Sociology Combined Program in Education and Psychology University of Maryland University of Michigan To capture the common features of diverse fundamentalist movements, overcome etymological variability, and assess predictors, religious fundamentalism is conceptualized as a set of beliefs about and attitudes toward religion, expressed in a disciplinarian deity, literalism, exclusivity, and intolerance. Evidence from representative samples of over 23,000 adults in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and Turkey supports the conclusion that fundamentalism is stronger in countries where religious liberty is lower, religion less fractionalized, state structure less fragmented, regulation of religion greater, and the national context less globalized. Among individuals within countries, fundamentalism is linked to religiosity, confidence in religious institutions, belief in religious modernity, belief in conspiracies, xenophobia, fatalism, weaker liberal values, trust in family and friends, reliance on less diverse information sources, lower socioeconomic status, and membership in an ethnic majority or dominant religion/sect. We discuss implications of these findings for understanding fundamentalism and the need for further research. Keywords: fundamentalism, Islam, Christianity, Sunni, Shia, Muslim-majority countries. INTRODUCTION -

Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran Laypeople Ashley Burgess Leininger Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2009 Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople Ashley Burgess Leininger Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Leininger, Ashley Burgess, "Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10805. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10805 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conceptualizations of God by Lutheran laypeople by Ashley Burgess Leininger A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Sociology Program of Study Committee: David Schweingruber, Major Professor Gloria Jones-Johnson Carl Roberts Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2009 Copyright © Ashley Burgess Leininger, 2009. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ v INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................