Pre-Nestorianism” in Spain: the Letter of Vitalis and Constantius and Pseudo-Athanasian De Trinitate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of the Idea of Nestorian Crosses— Based on Fa Nixon's

QUEST: Studies on Religion & Culture in Asia, Vol. 2, 2017 INVESTIGATION OF THE IDEA OF NESTORIAN CROSSES— BASED ON F. A. NIXON’S COLLECTION Chen, Jian Andrea Published online: 1 January 2017 ABSTRACT It is generally agreed that the study of the Nestorian Cross (a kind of bronze piece believed to be an early Chinese Christian relic), has great significance both for the developing study of Jingjiao and for ethnographic studies of the Nestorian Mongol people. The most important question that we should ask, however, is, “Are these so-called Nestorian Crosses part of the Mongolian Nestorian heritage?“ In other words, before starting to interpret the pieces in question, we need to ask if the identification, made at the first step of examination, is convincing enough as a basis upon which to build the interpretation. This paper focuses on issues concerning all aspects of the concept of Nestorian Crosses, looking first into the history of such an idea, then investigating its inner logic, and finally challenging its hard evidence. It is hoped that the conclusions of this paper will initiate a paradigm shift in the current study of this topic. Introduction to the Study The Jingjiao and the Yelikewen The name “Nestorian Crosses” clearly reveals that the religious dimension has been the primary consideration in the existing identification of these items, an identification which subsumes them as relics of Chinese Nestorianism, or more accurately, of the Jingjiao and the Yelikewen. Although controversies surround the identity of Nestorianism, the most commonly accepted description is as follows: At the Ephesus Council of 431 A.D., the Patriarch Nestorius was deemed heretical and his teaching anathematized due to his insistence that Mary should be called “Christotokos (Christ-bearer)” instead of “Theotokos (God-bearer).” This insistence is thought to emphasize a distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures instead of their unity. -

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism For the church sometimes known as the Nestorian Church, see Church of the East. "Nestorian" redirects here. For other uses, see Nestorian (disambiguation). Nestorianism is a Christological doctrine advanced by Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428–431. The doctrine, which was informed by Nestorius' studies under Theodore of Mopsuestia at the School of Antioch, emphasizes the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus. Nestorius' teachings brought him into conflict with some other prominent church leaders, most notably Cyril of Alexandria, who criticized especially his rejection of the title Theotokos ("Bringer forth of God") for the Virgin Mary. Nestorius and his teachings were eventually condemned as heretical at the First Council of Ephesus in 431 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451, leading to the Nestorian Schism in which churches supporting Nestorius broke with the rest of the Christian Church. Afterward many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to Sassanid Persia, where they affiliated with the local Christian community, known as the Church of the East. Over the next decades the Church of the East became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine, leading it to be known alternately as the Nestorian Church. Nestorianism is a form of dyophysitism, and can be seen as the antithesis to monophysitism, which emerged in reaction to Nestorianism. Where Nestorianism holds that Christ had two loosely-united natures, divine and human, monophysitism holds that he had but a single nature, his human nature being absorbed into his divinity. A brief definition of Nestorian Christology can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is not identical with the Son but personally united with the Son, who lives in him, is one hypostasis and one nature: human."[1] Both Nestorianism and monophysitism were condemned as heretical at the Council of Chalcedon. -

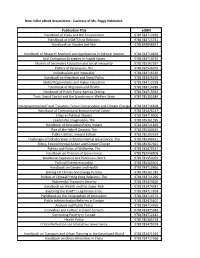

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Eph 5:1-2 A. Second-Personal Life with Jesus Christ, Rev. 3:14-22

Bible Doctrines (T/G/B ) Theology June 25, 2017 Eschatology Thanatology Ecclesiology Matthew 22:36-40; 2 Pet 1:2-4; 1 Cor 13:1-7; Eph 5:1-2 Israelology Dispensationalism Doxology A. Second-personal life with Jesus Christ, Rev. 3:14-22. Hodology Soteriology - 8 principles on life with Christ and the problem of a closed heart. Hamartiology Natural Law Anthropology B. Through the Bible, Rom 11:1-16: The hardening of Israel. Angelology - 5 reasons God is not through with Israel. Pneumatology Christology Paterology C. Hermeneutics: Natural Law 32, Rom 2:14. Natural Law and America’s Trinitarianism Cosmology founding fathers. Theology Proper - 6 principles on natural law and the American experiment. Bibliology Natural Theology Foundations/Reality 7 Hermeneutics 33 D. Bible doctrine: the Glory of God 35 (John 1:14; 12:23-24; 13:31-32; 17:1; -Natural Law-31 1 Cor 1:27-31). 6 Science 51 5 Language 155 - 6 principles on the glory of God. 4 Epistemology 32 Existence 50 History 50 3 Metaphysics 32 Trans. 50 2 Reality - Logic, 32 http://www.fbcweb.org/sermons.html - Truth, 32 1 Realism – 32 Historical overview of Christology on how “the Word BECAME flesh/sarx.” 1. Rejection of Ebionism (denial of Jesus’s divinity), a Jewish heresy (contra 1 John 2:2). 2. Rejection of Docetism (denial of Jesus’s human nature), contra 1 Jn 4:3; 2 John 4:7. 3. Ignatius (d. 170) defends Incarnation against Docetism with “Communicatio idiomatum.” 4. Justin Martyr the apologist (d. 165) defends transcendence of the Logos using Stoic concepts. -

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate

The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate by David Andrew Graham A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by David Andrew Graham 2013 The Christological Function of Divine Impassibility: Cyril of Alexandria and Contemporary Debate David Andrew Graham Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis contributes to the debate over the meaning and function of the doctrine of divine impassibility in theological and especially christological discourse. Seeking to establish the coherence and utility of the paradoxical language characteristic of the received christological tradition (e.g. the impassible Word became passible flesh and suffered impassibly), it argues that the doctrine of divine apatheia illuminates the apocalyptic and soteriological dimension of the incarnate Son’s passible life more effectively than recent reactions against it. The first chapter explores the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria and the meaning and place of apatheia within it. In light of the christological tradition which Cyril epitomized, the second chapter engages contemporary critiques and re-appropriations of impassibility, focusing on the particular contributions of Jürgen Moltmann, Robert W. Jenson, Bruce L. McCormack and David Bentley Hart. ii Acknowledgments If this thesis communicates any truth, beauty and goodness, credit belongs to all those who have shaped my life up to this point. In particular, I would like to thank the Toronto School of Theology and Wycliffe College for providing space to do theology from within the catholic church. -

Evangelism and Capitalism: a Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 6-2018 Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship Jason Paul Clark George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Jason Paul, "Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship" (2018). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 132. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVANGELICALISM AND CAPITALISM A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Paul Clark Middlesex University Supervised at London School of Theology June 2018 Abstract Jason Paul Clark, “Evangelicalism and Capitalism: A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship.” Doctor of Philosophy, Middlesex University, 2018. No sustained examination and diagnosis of problems inherent to the relationship of Evangeli- calism with capitalism currently exists. Where assessments of the relationship have been un- dertaken, they are often built upon a lack of understanding of Evangelicalism, and an uncritical reliance both on Max Weber’s Protestant Work Ethic and on David Bebbington’s Quadrilateral of Evangelical priorities. -

The Truth of Divine Impassibility: a New Look at an Old Argument Jeffrey G Silcock

198 Jeffrey G Silcock The truth of divine impassibility: a new look at an old argument Jeffrey G Silcock Jeff is head of the History and Systematic Theology Department at ALC and serves as chair of the LCA’s Commission on Theology and Inter-Church Relations. Introduction From his Nazi prison cell in 1944, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote to his friend Eberhard Bethge that ‘only the suffering God can help’.1 Just after the war, the Japanese Lutheran theologian Kazoh Kitamori published his ground-breaking book, Theology of the pain of God,2 based around Jeremiah 31:20, where he developed a similar theology of the cross: the pain of God heals our pain. In the suffering of Christ, God himself suffers. In 1973 Jürgen Moltmann came out with his classic, The crucified God, where he takes this further and develops a critical theology of the cross. He holds that a ‘theology after Auschwitz’ has to revise completely the traditional doctrine of God that teaches divine impassibility. Moltmann at the outset reflects on his own experience: ‘Shattered and broken, the survivors of my generation were then returning from camps and hospitals to the lecture room. A theology which did not speak of God in the sight of the one who was abandoned and crucified would have had nothing to say to us then’.3 The old teaching of classical theism that God is beyond suffering died in the death camps of WWII and was no longer tenable. Moltmann wrote his book, which had an enormous impact in its day, with the conviction that only if God is not detached from human suffering, but willingly enters into it with compassion, is there any hope for the future. -

Early-Christianity-Timeline.Pdf

Pagan Empire Christian Empire 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 1 AD Second 'Bishop' of Rome. Pupil of Student of Polycarp. First system- Bishop of Nyssa, brother of Basil. Pope. The Last Father of the Peter. Author of a letter to Corinth, atic theologian, writing volumi- Bishop of Original and sophisticated theologi- model of St Gregory the Church. First of the St John of (1 Clement), the earliest Christian St Clement of Rome nously about the Gospels and the St Irenaeus St Cyprian Carthage. an, writing on Trinitarian doctrine Gregory of Nyssa an ideal Scholastics. Polymath, document outside the NT. church, and against heretics. and the Nicene creed. pastor. Great monk, and priest. Damascus Former disciple of John the Baptist. Prominent Prolific apologist and exegete, the Archbishop of Constantinople, St Leo the Pope. Able administrator in very Archbishop of Seville. Encyclopaedist disciple of Jesus, who became a leader of the most important thinker between Paul brother of Basil. Greatest rhetorical hard times, asserter of the prima- and last great scholar of the ancient St Peter Judean and later gentile Christians. Author of two St Justin Martyr and Origen, writing on every aspect stylist of the Fathers, noted for St Gregory Nazianzus cy of the see of Peter. Central to St Isidore world, a vital link between the learning epistles. Source (?) of the Gospel of Mark. of life, faith and worship. writing on the Holy Spirit. Great the Council of Chalcedon. of antiquity and the Middle Ages. Claimed a knowledge and vision of Jesus independent Pupil of Justin Martyr. Theologian. -

Divine Presence Theology Versus Name Theology in Deuteronomy.”

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 55, No. 1, 3. Copyright © 2017 Andrews University Seminary Studies. RETRACTION FOR PLAGIARISM: ROBERTO OURO, “DIVINE PRESENCE THEOLOGY VERSUS NAME THEOLOGY IN DEUTERONOMY.” The editors of Andrews University Seminary Studies retract the following article by Roberto Ouro because of plagiarism: “Divine Presence Theology versus Name Theology in Deuteronomy” AUSS 52.1 (2014): 5–29. This article is retracted because the author plagiarized substantial portions from another work, misrepresenting the argumentation of the article as original work. This retraction has no bearing on the validity of the sources from which the article draws. 3 Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 52, No. 1., 5-29. Copyright © 2014 Andrews University Press. DIVINE PRESENCE THEOLOGY VERSUS NAME THEOLOGY IN DEUTERONOMY ROBERTO OURO Adventist School of Theology Valencia, Spain Introduction Name Theology has long been understood by biblical scholars to be evidence of a paradigm shift within the Israelite theology of Divine Presence. This paradigm shift involves a supposed evolution in Israelite religion away from the anthropomorphic and immanent images of the deity, as found in Divine Presence Theology, toward a more abstract, demythologized, and transcendent one, as in Name Theology. According to Name Theology, the book of Deuteronomy is identifi ed as the transition point in the shift from the “older and more popular idea” that God lives in the temple with the idea that he is actually only hypostatically present in the temple. This new understanding theologically differentiates between “Jahweh on the one hand and his name on the other.”1 The residual effect of Name Theology is acutely evident in its immanence–to-transcendence scheme. -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

3. Unification Christology

Volume XXI - (2020) Unification Christology THEODORE SHIMMYO • Shimmyo, Theodore T. Journal of Unification Studies Vol. 21, 2020 - Pages 51-76 In the history of Christianity theology, there has been a conflict between two types of Christology: "high" and "low" Christology. High Christology, which is orthodox Christology, holds that Christ, as the divine Logos "consubstantial" (homoousios) with God the Father, is actually God who assumes a human nature added as a "nature in the person" (physis enhypostatos) of none other than the divine Logos after the incarnation.[1] Christ, then, is not a human being in the same sense that we are human beings. By contrast, low Christology, which is liberal Christology, believes that Christ is a real man with a real human nature who assumes only some or no divinity. Now, according to Unification Christology in Exposition of the Divine Principle, Jesus is "a man who has completed the purpose of creation."[2] This certainly gives the impression as if Unification Christology were a low Christology. In actuality, however, Unification Christology is far from being a low Christology, as it recognizes his full divinity unlike low Christology which does not. Unification Christology firmly believes that Jesus as a man possesses "the same divine nature as God," by completing "the purpose of creation" at the individual level, i.e., by becoming "a person of perfect individual character" who is "perfect as God is perfect"[3] and who is in "inseparable oneness with" God, assuming "a divine value, comparable to God."[4] If Unification Christology is thus not a low Christology, it is obviously not a high Christology, either. -

Nestorians Jǐngjiàotú 景教徒

◀ Neo-Confucianism Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Nestorians Jǐngjiàotú 景教徒 Nestorians refer to Christians who follow Nestorians first translated their scriptures into Chinese Nestorius, a leader of an early Eastern Chris- and established a Nestorian church in Chang’an. After tian tradition. Persecution for heresy forced the that many Nestorians came to China either by land from Nestorians toward Central and East Asia, includ- Central Asia or by sea from Persia (Iran). The Nestorian Stele was erected in 781, a time of relative prosperity for ing China. As the first generation of Christians Chinese Nestorianism. It is said to have been inscribed coming to China, they arrived in the Tang court by a Nestorian priest named “Adam” (“Jingjing” in Chi- in the early seventh century, and remained in the nese) with the sponsorship of a larger congregation. The country for two hundred years. stele offers a brief but thorough history of Nestorianism in Tang China. According to manuscript sources, the Ne- storian leader Adam translated about thirty-five scriptures hristianity was introduced to China during the into Chinese. Several of these translations survived as the Tang dynasty (618– 907 ce) and became widely manuscripts from Dunhuang; one of them is identified as known as “Jingjiao” (Luminous Teaching) dur- Gloria in excélsis Deo in Syriac texts. However, after 845 ing the Tianqi period (1625– 1627) of the Ming dynasty the Nestorians virtually disappeared in Chinese sources, (1368– 1644) after the discovery of a luminous stele (a having suffered political persecution under the reign of carved or inscribed stone slab or pillar used for commem- the Emperor Wuzong.