Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As a Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference 28 and 29 May 2019 https://www.regioparl.com/parliamentary-voices-on-the-future-of-europe/?lang=en Conference Report © Picture: European Parliament 1 Conference Report Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference, 28 & 29 May 2020 Governance in Europe is built on a diverse multi-level parliamentary system, making parliaments at all levels – European, national, and subnational – key actors in the functioning of any democratic political process involving the future of Europe. This is why parliaments took centre stage in the two-day digital conference, which brought together academics and policy makers from all political levels – European, national, and subnational – in order to encourage an exchange of views between politics and academia. The event touched upon various issues of parliamentary involvement in the European Union (EU), such as the democratic legitimacy of EU politics, parliamentary scrutiny of European policies and Europeanisation of national and subnational parliaments. Aiming at fostering a debate between research and politics, it brought together a number of outstanding experts from academia and politics, who contributed to very insightful and lively debates on (1) the current state of play of parliamentary voices in the EU and (2) opportunities and obstacles for a strengthening of parliamentary voices in the future of the EU, in general, and in the upcoming EU Conference on the Future of Europe to be kicked-off in autumn, in particular. This conference report presents a summary of the various programme points, including keynotes and Q&A sessions as well as panel discussions and roundtables. -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

Germany: Baffled Hegemon Constanze Stelzenmüller

POLICY BRIEF Germany: Baffled hegemon Constanze Stelzenmüller Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany has transformed into a hegemonic power in Europe, but recent global upheaval will test the country’s leadership and the strength of its democracy. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY are challenging Europe’s cohesion aggressively, as does the Trump administration’s “America First” The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 turned reunified policy. The impact of this on Germany is stark. No Germany into Europe’s hegemon. But with signs of country in Europe is affected so dramatically by this a major global downturn on the horizon, Germany new systemic competition. Far from being a “shaper again finds itself at the fulcrum of great power nation,” Germany risks being shaped: by events, competition and ideological struggle in Europe. And competitors, challengers, and adversaries. German democracy is being challenged as never before, by internal and external adversaries. Germany’s options are limited. It needs to preserve Europe’s vulnerable ecosystem in its own The greatest political challenge to liberal democracy enlightened self-interest. It will have to compromise within Germany today is the Alternative für on some issues (defense expenditures, trade Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, or AfD), the surpluses, energy policy). But it will also have to first far-right party in the country’s postwar history push back against Russian or Chinese interference, to be represented in all states and in the federal and make common cause with fellow liberal legislature. While it polls nationally at 12 percent, its democracies. With regard to Trump’s America, disruptive impact has been real. -

Introducing Eastern Germany's Far-Right Intellectuals I EUROPP

16.02.2021 Introducing eastern Germany's far-right intellectuals I EUROPP Q Biog Team February 11 th, 2020 Introducing eastern Germany's far-right intellectuals O comments Estimated reading time: 5 minutes On 5 February, Thomas Kemmerich of the FreeDemocratic Party {FDP) was elected as Minister President of Thuringia with thehelp of the Alternative for Germany {AfD). Sabine Volk explains that the incident, which has generated a heated reaction in Germany, highlights the role of far-right groups in shaping public debate in eastern Germany. Following the AfD's coup in Thuringia and the resulting political earthquake in German party politics, eastern Germany has once again moved into the spotlight of national debates on rising far-right populism. I have recently conducted research in the region, where far- https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2020/02/11/introducing-eastern-germanys-far-right-intellectuals/ 1/8 16.02.2021 Introducing eastern Germany's far-right intellectuals I EUROPP right subcultures have been able to establish themselves, providing a platform for far-right debate and networking. Once in a blue moon, a public bus goes to Schnellroda, a tiny township in the eastern German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt. About fifty kilometres from Saxony's buzzing student city of Leipzig, and some thirty kilometres away from the city of Halle, the location of an anti Semitic terrorist attack in October last year, this remote place is the embodiment of 'the middle of nowhere'. Yet, Germany's far-right scene usually spares no effort to gather in Schnellroda. It is here that Germany's leading far-right intellectual, Gotz Kubitschek, his so-called Institute for State Politics (lfS), and his publishing house Antaiosreside. -

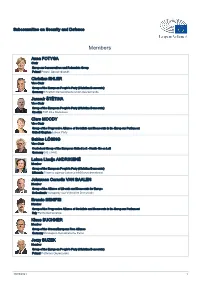

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Representation and Global Power in A

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Senior Theses International Studies Spring 5-19-2018 Representation and Global Power in a Multicultural Germany: A Discourse Analysis of the German Response(s) to the Presence of Syrian Refugees Kyle William Zarif Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/international_senior Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zarif, Kyle William, "Representation and Global Power in a Multicultural Germany: A Discourse Analysis of the German Response(s) to the Presence of Syrian Refugees" (2018). Senior Theses. 7. https://fordham.bepress.com/international_senior/7 This is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! Representation and Global Power in a Multicultural Germany A Discourse Analysis of the German Response(s) to the Presence of Syrian Refugees ! ! ! ! ! ! Kyle Zarif Fordham University International Studies Program Global Affairs Track Thesis Seminar Professor: Dr. Hill Krishnan Primary Advisor: Dr. Hugo Benavides Email: [email protected] ! ! ! ! Zarif !1 ! Table of Contents! 1. Introduction I. Thesis Statement and Research Questions ......2 II. [Muslim] Refugees: A Great Challenge [for Germany and Europe] ......3 III. The EU and Syria: Framing the German Approach to Refugees ......5 IV. Cultural Politics and the Stigmatization of European Muslims ......8 V. Implications for Syrian Refugees ......10 !VI. Relevant Theory: Discourse(s), Knowledge and Global Power ......11 3. Syrian Refugees in the Mainstream German Media I. -

Ipi Congress Report 2

SALZBURG IPI CONGRESS REPORT 2www.freemedia.at003 IPI WORLD CONGRESS & 52nd GENERAL ASSEMBLY IPI Congress Report CONTENTS Programme ................................................ 1 Editorial........................................................ 4 Opening Ceremony .............................. 6 Pluralism, Democracy and the Clash of Civilisations ................14 INTERNATIONAL Analysing the World Summit PRESS INSTITUTE on the Information Society............ 24 Chairman SARS and the Media ........................ 30 Jorge E. Fascetto Chairman of the Board, Diario el Día La Plata, Argentina IPI Free Media Pioneer 2003 ...... 38 Director Congress Snapshots ........................ 40 Johann P. Fritz Media in War Zones Congress Coordinator and and Regions of Conflict .................. 42 Editor, IPI Congress Report Michael Kudlak The International News Safety Institute........................ 52 Assistant Congress Coordinator Christiane Klint Media Self-Regulation: A Press Freedom Issue .................. 56 Congress Transcripts Rita Klint The Transatlantic Rift ........................ 64 International Press Institute (IPI) The Oslo Accords Spiegelgasse 2/29, A-1010 Vienna, Austria – 10 Years On........................................ 74 Tel: +43-1-512 90 11, Fax: +43-1-512 90 14 E-mail: [email protected], http://www.freemedia.at Farewell Remarks................................ 77 Cover Photograph: Tourismus Salzburg GmbH • Layout: Nik Bauer Printing kindly sponsored by Heidelberger Druckmaschinen Osteuropa Vertriebs-GmbH Paper kindly -

Afd) a New Actor in the German Party System

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) A New Actor in the German Party System MARCEL LEWANDOWSKY March 2014 The Alternative für Deutschland (AfD – Alternative for Germany) is a new party in the conservative/economic liberal spectrum of the German party system. At present it is a broad church encompassing various political currents, including classic ordo-liberals, as well as euro-sceptics, conservatives and right-wingers of different stripes. The AfD has not yet defined its political platform, which is still shaped by periodic flare-ups of different groups positioning themselves within the party or by individual members. The AfD’s positions are mainly critical of Europe and the European Union. It advo- cates winding up the euro area, restoration of national currencies or small currency unions and renationalisation of decision-making processes in the EU. When it comes to values it represents conservative positions. As things stand at the moment, given its rudimentary political programme, the AfD is not a straightforward right-wing populist party in the traditional sense. The populist tag stems largely from the party’s campaigning, in which it poses as the mouthpiece of »the people« and of the »silent majority«. With regard to its main topics, the AfD functions as a centre-right protest party. At the last Bundestag election in 2013 it won voters from various political camps. First studies show that although its sympathisers regard themselves as occupying the political centre, they represent very conservative positions on social and integra- tion-policy issues. Marcel Lewandowsky | ALternativE füR DEutschland (AfD) Content 1. Origins and Development. -

The Afd's Second Place in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania Illustrates the Challenge Facing Merkel in 2017

The AfD’s second place in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania illustrates the challenge facing Merkel in 2017 blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/09/05/afd-mecklenburg-west-pomerania-merkel/ 05/09/2016 Angela Merkel’s CDU came third behind the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the German Social Democrats (SPD) in elections in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania on 4 September. Kai Arzheimer writes that while the result was not unexpected and the CDU still has a lead in national polling, the election underlines the challenge facing Merkel as she seeks reelection in the next German federal elections in 2017. The result of the regional election in the north-eastern state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania could hardly be more embarrassing for Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel. Her Christian Democrats (CDU) finished third with just 19 per cent of the vote, behind the new-ish ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD) party that won 20.8 per cent. The AfD takes its very name from Merkel’s frequent claim that there was ‘no alternative’ to her policies, and the slogan ‘Merkel muss weg‘ (Merkel must go) has become something like a mantra for her detractors on the right. With one year to go until the next German federal election, the result does not bode well for Merkel and the CDU. However, sensitivities and the symbolism of coming second or third aside, the result was no huge surprise, and its short-term impact will be limited. Support for the AfD is generally higher in the eastern states than it is in the West, and Mecklenburg-West Pomerania in particular has a long history of right-wing mobilisation both inside and outside parliament (although the state’s immigrant population is tiny). -

View / Open Final Thesis-Hauth Q

HOW MIGRATION HAS CONTRIBUTED THE RISE OF THE FAR-RIGHT IN GERMANY by QUINNE HAUTH A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Quinne Hauth for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken June 2019 Title: How Migration Has Contributed to the Rise of the Far-Right in Germany Approved: _______________________________________ Angela Joya Increased migration into Europe in the summer of 2015 signified a shift in how the European Union responds to migration, and now more so than in Germany, which has opened its doors to about 1.5 million migrants as of 2018. While Chancellor Angela Merkel’s welcome helped alleviate the burden placed on countries that bordered the east as well as the Mediterranean, it has been the subject of a lot of controversy over the last three years within Germany itself. Drawing on this controversy, this study explores how migration has affected Germany’s migration policies, and the extent to which it has affected a shift towards the right within the government. I conclude that Germany’s relationship with migration has been complicated since its genesis, and that ultimately Merkel’s welcome was the exception to decades of policy, not the rule. Thus, as tensions increase between migrants and citizens, and policy fails to adapt to benefit both parties, Germany’s politicians will advocate to close the state from migrants more and more. -

![The Green Party of Germany: Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6046/the-green-party-of-germany-b%C3%BCndnis-90-die-gr%C3%BCnen-pdf-1076046.webp)

The Green Party of Germany: Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen [PDF]

THE GREEN PARTY OF GERMANY BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN 1. Historical Context and democratic structure of Germany The political structures that existed before a united German state emerged were dominated by relatively small political entities, which enjoyed varying degrees of political autonomy. The Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Federal Republic of Germany) is formally only 70 years old. Unsurprisingly, this history of federalism is represented in the Bundesrepublik as well. Today we have 16 federal states. This decentralization is one of the most important parts of our democracy. Berlin, as the capital, was and is the best symbol of Germany’s colourful past. West Berlin’s location deep within the territory of Eastern Germany made it an island of the Bundesrepublik (Western Germany). West Berlin has had a very special phase after WWII that was deeply intertwined with the Cold War. With the end of the Cold War, the two German states the German Democratic Republic or GDR (East Germany) and Bundesrepublik finally became a united state again. Today, Berlin with its 3.6 million inhabitants, is Germany’s biggest city, its capital and the place to be for culture, arts, lifestyle, politics and science. Germany’s democratic system is a federal parliamentary republic with two chambers: the Bundestag (Germany’s parliament) and the Bundesrat (the representative body of the federal states). Germany’s political system is essentially a multi-party system, which includes a 5% threshold (parties representing recognised national minorities, for example Danes, Frisians, Sorbs and Romani people are exempt from the 5% threshold, but normally only run in state elections).