George P. Novotny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Davis-Monthan Afb 1940 - 1976 Preface

DAVIS-MONTHAN AFB 1940 - 1976 PREFACE This history, in its final form, is the result of almost three years of off-and-on effort on the part of this historian. It has had to be sandwiched in between the myriad taskings associated with three different assignments. It began at Davis-Monthan AFB in 1979 while assigned there as the historian for the 390th Strategic Missile Wing. My research notes and supporting documents came with me when I was subsequently transferred to the Headquarters SAC Office of the Historian and then later to the 4000th Satellite Operations Group at Offutt AFB, Nebraska. The need for a complete base history became painfully obvious as soon as I began my initial research. There was very little data available at Davis-Monthan AFB concerning the history of the installation; other than a few short Information Office history handouts of the type often given to newcomers and visitors. The majority of substantive material on base activities over the years had been lost as host units switched repeatedly throughout the station’s existence. Those units were subsequently inactiviated or transferred to other bases. Accordingly, the majority of material presented herein had to be obtained at the Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center, Maxwell AFB, Alabama. Without the invaluable assistance of the many dedicated professionals at the Simpson Center, this history could never have been compiled. The transfer of Davis-Monthan AFB from the Strategic Air Command to the Tactical Air Command on 30 September 1976 ends the period of -

University of Maine, World War II, in Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine General University of Maine Publications University of Maine Publications 1946 University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K) University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Repository Citation University of Maine, "University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)" (1946). General University of Maine Publications. 248. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications/248 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in General University of Maine Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MAINE WORLD WAR II IN MEMORIAM DEDICATION In this book are the records of those sons of Maine who gave their lives in World War II. The stories of their lives are brief, for all of them were young. And yet, behind the dates and the names of places there shines the record of courage and sacrifice, of love, and of a devotion to duty that transcends all thought of safety or of gain or of selfish ambition. These are the names of those we love: these are the stories of those who once walked with us and sang our songs and shared our common hope. These are the faces of our loved ones and good comrades, of sons and husbands. There is no tribute equal to their sacrifice; there is no word of praise worthy of their deeds. -

Almanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide

USAFAlmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide Major Installations Note: A major installation is an Air Force Base, Air Andrews AFB, Md. 20762-5000; 10 mi. SE of 4190th Wing, Pisa, Italy; 31st Munitions Support Base, Air Guard Base, or Air Reserve Base that Washington, D. C. Phone (301) 981-1110; DSN Sqdn., Ghedi AB, Italy; 4190th Air Base Sqdn. serves as a self-supporting center for Air Force 858-1110. AMC base. Gateway to the nation’s (Provisional), San Vito dei Normanni, Italy; 496th combat, combat support, or training operations. capital and home of Air Force One. Host wing: 89th Air Base Sqdn., Morón AB, Spain; 731st Munitions Active-duty, Air National Guard (ANG), or Air Force Airlift Wing. Responsible for Presidential support Support Sqdn., Araxos AB, Greece; 603d Air Control Reserve Command (AFRC) units of wing size or and base operations; supports all branches of the Sqdn., Jacotenente, Italy; 48th Intelligence Sqdn., larger operate the installation with all land, facili- armed services, several major commands, and Rimini, Italy. One of the oldest Italian air bases, ties, and support needed to accomplish the unit federal agencies. The wing also hosts Det. 302, dating to 1911. USAF began operations in 1954. mission. There must be real property accountability AFOSI; Hq. Air Force Flight Standards Agency; Area 1,467 acres. Runway 8,596 ft. Altitude 413 through ownership of all real estate and facilities. AFOSI Academy; Air National Guard Readiness ft. Military 3,367; civilians 1,102. Payroll $156.9 Agreements with foreign governments that give Center; 113th Wing (D. C. -

Florida Statewide Aviation Economic Impact Study

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION STATEWIDE AVIATION Economic Impact Study 3 2 5 7 1 4 6 Technical Report 2019 Contents 1. Overview ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Study Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Communicating Results ................................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Florida’s Airports ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Study Conventions ...................................................................................................................... 10 1.5.1 Study Terminology .............................................................................................................. 10 1.6 Report Organization .................................................................................................................... 12 2. Summary of Findings ........................................................................................................................... 13 2.1 FDOT District Results .................................................................................................................. -

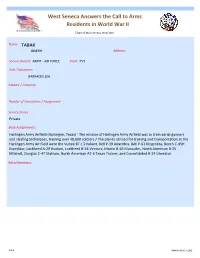

T Military Service Report

West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: TABAK JOSEPH Address: Service Branch:ARMY - AIR FORCE Rank: PVT Unit / Squadron: BARRACKS 206 Medals / Citations: Theater of Operations / Assignment: Service Notes: Private Base Assignments: Harlingen Army Airfield (Harlingen, Texas) - The mission of Harlingen Army Airfield was to train aerial gunners and strafing techniques, training over 48,000 soldiers / The planes utilized for training and transportation at the Harlingen Army Air Field were the Vultee BT-13 Valiant, Bell P-39 Airacobra, Bell P-63 Kingcobra, Beech C-45H Expeditor, Lockheed A-29 Hudson, Lockheed B-34 Ventura, Martin B-26 Marauder, North American B-25 Mitchell, Douglas C-47 Skytrain, North American AT-6 Texan Trainer, and Consolidated B-24 Liberator Miscelleaneous: 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: TAGLIAFERRO JOHN N. Address: 24 LENOX ROAD Service Branch:ARMY Rank: SGT Unit / Squadron: 119TH INFANTRY, 30TH INFANTRY DIVISION Medals / Citations: EUROPEAN-AFRICAN-MIDDLE EASTERN CAMPAIGN MEDAL PURPLE HEART Theater of Operations / Assignment: EUROPEAN THEATER Service Notes: Sergeant John N. Tagliaferro died in France from wounds received on the battlefield / Sergeant Tagliaferro had been an Infantryman in the Army for approximately three years and served overseas for one month / Sergeant John Tagliaferro was 24 years of age at the time of his death Sergeant John N. Tagliaferro is buried at Normandy American Cemetery (Colleville-sur-Mer, France) Base Assignments: Miscelleaneous: Employed as a Architect, John N. -

310Th FIGHTER SQUADRON

310th FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 310th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 21 Jan 1942 Activated, 9 Feb 1942 Redesignated 310th Fighter Squadron, 15 May 1942 Redesignated 310th Fighter Squadron, Single-Engine, 20 Aug 1943 Inactivated, 20 Feb 1946 Redesignated 310th Fighter-Bomber Squadron 25 Jun 1952 Activated, 10 Jul 1952 Redesignated 310th Tactical Missile Squadron, 15 Jul 1958 Discontinued and inactivated, 25 Mar 1962 Redesignated 310th Tactical Fighter Training Squadron, 11 Dec 1969 Activated, 15 Dec 1969 Redesignated 310th Fighter Squadron, 1 Nov 1991 STATIONS Harding Field, LA, 9 Feb 1942 Dale Mabry Field, FL, 4 Mar 1942 Richmond AAB, VA, 16 Oct 1942 Philadelphia Muni Aprt, PA, 24 Oct 1942 Bradley Field, CT, 5 Mar 1943 Hillsgrove, RI, 28 Apr 1943 Grenier Field, NH, 16 Sep–22 Oct 1943 Brisbane, Australia, c. 23 Nov 1943 Dobodura, New Guinea, 28 Dec 1943 Saidor, New Guinea, 2 Apr 1944 Noemfoor, 6 Sep 1944 San Roque, Leyte, 18 Nov 1944 San Jose, Mindoro, 22 Dec 1944 Mangaldan, Luzon, 6 Apr 1945 Porac, Luzon, 18 Apr 1945 Okinawa, 9 Jul 1945 Japan, 26 Oct 1945 Ft William McKinley, Luzon, 28 Dec 1945–20 Feb 1946 Taegu AB, South Korea, 10 Jul 1952 Osan-Ni (later, Osan) AB, South Korea, 19 Mar 1955–25 Mar 1962 Luke AFB, AZ, 15 Dec 1969 ASSIGNMENTS 58th Pursuit (later, 58th Fighter) Group, 9 Feb 1942 Fifth Air Force, 27 Jan–20 Feb 1946 58th Fighter-Bomber Group, 10 Jul 1952 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing, 8 Nov 1957 314th Air Division, 1 Jul 1958 58th Tactical Missile Group, 15 Jul 1958–25 Mar 1962 58th Tactical Fighter Training (later, 58th Tactical Training) Wing, 15 Dec 1969 58th Operations Group, 1 Oct 1991 56th Operations Group, 1 Apr 1994 ATTACHMENTS 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing, 1 Mar–7 Nov 1957 WEAPON SYSTEMS P–39, 1942 P-39D P-39F P–40, 1942–1943 P-40F P–47, 1943–1945 P-47C P-47D F–84, 1952–1954 F-84G F–86, 1954–1958 Matador, 1958–1962 A–7D, 1969–1971 F–4, 1971–1982 F-4C F–16, 1982 F-16A F-16B F-16C F-16D COMMANDERS Maj James D. -

Punta Gorda Army Air Field (PG AAF) Fact Sheet and Timeline 7 May 2015

Punta Gorda Army Air Field (PG AAF) Fact Sheet and Timeline 7 May 2015 All Punta Gorda Army Air Field data came from the archived military files of the A.F. Historical Research Agency. Punta Gorda Army Air Field history is contained on microfilm reel #B2479. 5 May 1942 Internal Army Air Corps memorandum with the 225 acre lease in Charlotte County for the Punta Gorda Airport. 27 May 1942 Initial air field site survey rejected a site 2 miles south of Punta Gorda and a site 7 miles north of Punta Gorda was also rejected. A desirable site was selected 2 miles southeast of the city. (Note: The site 2 miles southeast would have placed the airfield at the intersection of present day Airport Road and Taylor Road). The final selected site (present location) was 3 miles southeast of the city). Thursday, 1 October 1942 Punta Gorda Herald headline: “Army Air Field to be Built” Cost of air field project announced at $700,000 Construction of the first building began on/about 19 October 1942 (source: p 66, article) Runways under survey began on/about 27 October 1942 (source: p 67, article) Runway construction and roadway equipment arrived on 4 November 1942 (source: p 68, article) Additional land purchases 12 November 1942 (source: p 69, article) Land clearing for runway construction work continued the week of 14 January 1943 (p72) 5 October 1942 (Completion Report for Punta Gorda Air Field – no date listed for report) Punta Gorda Airfield, an Operational Training Unit Station (Medium Bombardment) was authorized October 5, 1942 by Directive A 6187. -

Bases, Aircrew Members for C-5, C-17, C-141, and the European Theater, Killed in Aircraft Acci- Dating to 1911

USAFAlmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide Major Installations Altus AFB, Okla. 73523-5000; within Altus city Marine Aircraft Gp. 49, Det. A; Air Force Re- 620th Ex. ABG, Camp Able Sentry, Macedonia; limits, 120 mi. SW of Oklahoma City. Phone: view Boards Agency. History: activated May 731st Munitions Support Sq., Araxos AB, Greece; 580-482-8100; DSN 866-1110. Majcom: AETC. 1943. Named for Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, Det. 1, Ex. Air Control Sq., Jacotenente, Italy. Host: 97th Air Mobility Wing. Mission: trains military air pioneer and WWII commander of History: one of the oldest Italian air bases, aircrew members for C-5, C-17, C-141, and the European theater, killed in aircraft acci- dating to 1911. USAF began operations 1954. KC-135 aircraft by operating AETC’s strategic dent May 3, 1943, in Iceland. Area: 6,853 Area: 1,467 acres. Runway: 8,596 ft. Altitude: airlift and aerial refueling flying training schools. acres. Runways: 9,755 ft. and 9,300 ft. Alti- 413 ft. Personnel: permanent party military, History: activated January 1943; inactivated tude: 281 ft. Personnel: permanent party mili- 3,900; DoD civilians, 241; local nationals, 550. May 1945; reactivated January 1953. Area: tary, 5,855; DoD civilians, 1,128; contract em- Housing: single family, officer, 22, enlisted, 6,981 acres. Runways: 13,440 ft., 9,000-ft. ployees, 584. Housing: single family, officer, 508; unaccompanied, UAQ/UEQ, 680; visiting, parallel runway, and 3,500-ft. assault strip. Al- 384, enlisted, 1,694; leased units, 414 off base; VOQ, 17, VAQ/VEQ, 12, DV suites, 5. -

53Rd TEST and EVALUATION GROUP

53rd TEST AND EVALUATION GROUP MISSION The 53rd Test and Evaluation Group execute operational test, evaluation and tactics development for America’s fighter and bomber aircraft. Aircraft assigned to the group include test-configured F-15, F-15E, F-16, A-10, HH-60 and F-22 aircraft with flying hours assigned to the B-1, B-2 and B-52 aircraft. The group also conducts operational test and evaluation of the Global Hawk and Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and soon will begin testing of the Airborne Laser System. The 53d Test and Evaluation Group is made up of seven squadrons, two direct-reporting detachments, a named flight, and an operating location across nine stateside locations. The 53d TEG is responsible for the overall management of the wing’s flying activities at Barksdale, Beale, Dyess, Edwards, Eglin, Nellis, Whiteman, and Creech Air Force bases. Members of the group execute operational test and evaluation and tactics development and evaluation projects for Headquarters Air Combat Command. Detachment 2 of the 53d TEG at Beale Air Force Base, Calif., executes Force Development Evaluation of the U-2 and RQ-4 High Altitude weapon systems. They provide experienced operation, maintenance, engineering, and analysis personnel who plan and conduct ground and flight tests, analyze, evaluate, and report on the effectiveness, suitability and all related logistics, support, and training issues. Results and conclusions support DoD deployment and employment decisions. Detachment 3 of the 53d TEG at Nellis AFB is the representative for ACC interests in FME testing with AFMC. The detachment’s primary mission is to ensure USAF combat aircrews are prepared to fight with the latest knowledge available through FME. -

West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II

West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: SAGER ALBERT Address: Service Branch:ARMY Rank: PVT Unit / Squadron: HEADQUARTERS COMPANY, T.C. SCHOOL N.O.A.A.B. (NATIONAL OCEANIC & ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION) Medals / Citations: Theater of Operations / Assignment: Service Notes: Private Base Assignments: Camp Plauche (New Orleans, Louisiana) - Camp Plauche was originally known as Camp Harahan / It was renamed in honor of Major Jean Baptiste Plauche, who served under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans / During World War II, Camp Plauche was, first, a staging area for troops, then, an Army training facility and, later a POW camp for German and Italian prisoners Miscelleaneous: The mission of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was to monitor and forecast weather for worldwide military operations / NOAA printed tens of millions of nautical charts, aeronautical charts and other maps / Over 2,500 separate bomb target charts including for such areas as Ploesti Oil Field, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were printed for the military 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: SAGER R. J. Address: Service Branch: Rank: Unit / Squadron: Medals / Citations: Theater of Operations / Assignment: Service Notes: Base Assignments: Miscelleaneous: (NO OTHER INFORMATION AVAILABLE) 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: SAGER W. L. Address: Service Branch: Rank: Unit / Squadron: Medals / Citations: Theater of Operations / Assignment: Service Notes: Base Assignments: Miscelleaneous: (NO OTHER INFORMATION AVAILABLE) 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: SALISBURY CHESTER S. -

2010 USAF Almanac

Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide ■ 2010 USAF Almanac Major Active Duty Installations Altus AFB, Okla. 73523-5000; 120 mi. SW of Okla- Chief of the Army Air Forces. Area: 39,081 acres. Housing: single family, officer, 159, enlisted, 869; homa City. Phone: 580-482-8100; DSN 866-1110. Runway: 6,000 ft. Altitude: 1,100 ft. Personnel: unaccompanied, 570; visiting, VOQ, 50, VAQ/VEQ, Majcom: AETC. Host: 97th Air Mobility Wing. Mis- permanent party military, 58; DOD civilians, 240. 125, TLF, 28. Clinic. sion: forging combat mobility forces and deploying Housing: single family, officer, 19, enlisted, 21; airman warriors. History: activated January 1943; visiting, 34. Medical aid station, VA clinic. Buckley AFB, Colo. 80011-9524; 8 mi. E of Denver. inactivated May 1945; reactivated January 1953. Phone: 720-847-9011 DSN 847-9011. Majcom: Area: 7,746 acres. Inside Runway: 13,440 ft. Aviano AB, Italy, APO AE 09604; adjacent to Aviano, AFSPC. Host: 460th Space Wing. Mission: provides Outside Runway: 9,000 ft. Assault Strip: 3,515 50 mi. N of Venice. Phone: (cmcl, from CONUS) global surveillance, space-based missile warning, ft. Altitude: 1,381 ft. Personnel: permanent party 011-39-0434-30-1110; DSN 314-632-1110. Maj- and space communications operations. Major ten- military, 1,332; DOD civilians, 1,286. Housing: single com: USAFE. Host: 31st Fighter Wing. Mission: ants: 140th Wing (ANG); Aerospace Data Facility; family, 797; visiting, VOQ/VAQ, 315, TLF, 30. Clinic. F-16 and control and surveillance operations. Navy/Marine Reserve Center; Army Aviation Support Maintains two F-16 squadrons (510th and 555th) Facility. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive Data

.. MacOill Air Force Base HABS No. Fl-384 Bounded by the City of Tampa to the north, Tampa Bay to the south, Old Tampa Bay to the west, and Hillsborough Bay to the east Tampa Hillsborough County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Southeast Regional Department of the Interior Atlanta, Georgia 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MACDILL AIR FORCE BASE HABS No. Fl-384 location: The Base's northern boundary is the City of Tampa, which is separated by a security fence with check points on Bayshore Drive, MacDill Avenue and Dale Mabry (Highway 41). The Base is surrounded on the remaining three sides by water: Hillsborough Bay on the east side, Tampa Bay to the south, and Old Tampa Bay on the west side. Downtown Tampa is ten miles northeast of the north main (Dale Mabry) gate of the Base. Tampa, Hi1lsborough County, Florida U.S.G.S. Port Tampa & Gibsonton, Florida 7.5' Quadrangles Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates on Gibsonton Quadrangle: 17-353560-3081590 Present Owner: Department of the Air Force Present Occupants: MacDill Air Force Base 6th Air Base Wing Present Use: Military--Air Force Significance: The period of significance of MacDill Air Force Base is 1939 to 1945. The Base, along with seven other installations, was planned through the National Defense Act of 1935 which was sponsored by Senator J. Mark Wilcox of West Palm Beach, Florida. At this time, the world democracies were b~1ng threatened by the military act ions of Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union.