Chamicuro Data: Lateral Allophones Datos Del Chamicuro: Alófonos Laterales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARAWAK LANGUAGES” by Alexandra Y

OXFORD BIBLIOGRAPHIES IN LINGUISTICS “ARAWAK LANGUAGES” by Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald © Oxford University Press Not for distribution. For permissions, please email [email protected]. xx Introduction General Overviews Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters North Arawak Languages Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Reference Works Grammatical and Lexical Studies Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Specific Issues in the Grammar of North Arawak Languages Mixed Arawak-Carib Language and the Emergence of Island Carib Language Contact and the Effects of Language Obsolescence Dictionaries of North Arawak Languages Pre-andine Arawak Languages Campa Languages Monographs and Dissertations Articles and Book Chapters Amuesha Chamicuro Piro and Iñapari Apurina Arawak Languages of the Xingu Indigenous Park Arawak Languages of Areas near Xingu South Arawak Languages Arawak Languages of Bolivia Introduction The Arawak family is the largest in South America, with about forty extant languages. Arawak languages are spoken in lowland Amazonia and beyond, covering French Guiana, Suriname, Guiana, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Brazil, and Bolivia, and formerly in Paraguay and Argentina. Wayuunaiki (or Guajiro), spoken in the region of the Guajiro peninsula in Venezuela and Colombia, is the largest language of the family. Garifuna is the only Arawak language spoken in Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala in Central America. Groups of Arawak speakers must have migrated from the Caribbean coast to the Antilles a few hundred years before the European conquest. At least several dozen Arawak languages have become extinct since the European conquest. The highest number of recorded Arawak languages is centered in the region between the Rio Negro and the Orinoco. -

Handouts for Advanced Phonology: a Course Packet Steve Parker GIAL

Handouts for Advanced Phonology: A Course Packet Steve Parker GIAL and SIL International Dallas, 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Steve Parker and other contributors Page 1 of 281 Preface This set of materials is designed to be used as handouts accompanying an advanced course in phonology, particularly at the graduate level. It is specifically intended to be used in conjunction with two textbooks: Phonology in generative grammar (Kenstowicz 1994), and Optimality theory (Kager 1999). However, this course packet could potentially also be adapted for use with other phonology textbooks. The materials included here have been developed by myself and others over many years, in conjunction with courses in phonology taught at SIL programs in North Dakota, Oregon, Dallas, and Norman, OK. Most recently I have used them at GIAL. Many of the special phonetic characters appearing in these materials use IPA fonts available as freeware from the SIL International website. Unless indicated to the contrary on specific individual handouts, all materials used in this packet are the copyright of Steve Parker. These documents are intended primarily for educational use. You may make copies of these works for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. However, republication or commercial use of these materials is expressly prohibited without my prior written consent. Steve Parker Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics Dallas, 2018 Page 2 of 281 1 Table of contents: list of handouts included in this packet Day 1: Distinctive features — their definitions and uses -Pike’s premises for phonological analysis ......................................................................... 7 -Phonemics analysis flow chart .......................................................................................... -

Rethinking the Andes-Amazonia Divide

3.4 Broad- scale patterns across the languages of the Andes and Amazonia Paul Heggarty 1. Themes and structure This chapter provides an overview of the broadest- scale perspectives that linguis- tics can offer on our theme of an Andes– Amazonia divide. It follows the same contrast as in Chapter 1.2, between two fundamental and opposing linguistic con- cepts, each with their corresponding signals of the human past. Section 2 looks at language families, created by and attesting to past processes of geographical expansion and divergence. Section 3 looks at linguistic convergence, attesting to processes of interaction between past societies. Section 4 concludes by stepping back to a final, broadest, worldwide perspective on the validity of a divide between the languages of the Andes and of Amazonia. 2. Language families: Expansions and divergence Respecting or bridging the Andes– Amazonia divide? As already explored at the start of Chapter 1.2, the most far- dispersed lan- guage family in South America is Arawak. Although considered quintessentially Amazonian, it nonetheless ranges far beyond Amazonia proper. This only makes it all the more telling, then, that the one environmental frontier that it did balk at was that between Amazonia and the Andes (see section 3 below, for the borderline case of Yanesha, spoken up to 1,800 m in central Peru). But what of the other three main language families of lowland South America? The Tupí family was similarly very expansive within Amazonia and beyond, along the coast of Brazil and into the Chaco. It includes notably the Guaraní language, spoken particularly in Paraguay and lowland Bolivia. -

Chamicuro Data: Exhaustive List Datos Del Chamicuro: Lista Exhaustiva

Chamicuro data: exhaustive list Datos del chamicuro: lista exhaustiva Steve Parker Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, University of North Dakota, and SIL International SIL Language and Culture Documentation and Description 12 ©2010 Steve Parker, and SIL International ISSN 1939-0785 Fair Use Policy Documents published in the Language and Culture Documentation and Description series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of Language and Culture Documentation and Description or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor George Huttar Copy Editors Betty Philpott Mary Ruth Wise Compositor Judy Benjamin Abstract In this paper I present a more or less exhaustive list of all of the data that I collected which illustrate the phonological system of Chamicuro, an extinct Arawakan language of Peru. Both the instructions (metadata) and the glosses for the actual linguistic forms are given in Spanish as well as in English. Introduction In this article I present a more or less exhaustive list of all of the data that I collected and which illustrate the phonological system of the Chamicuro language of Peru. This introductory section of the paper describes the following Chamicuro data, including the purpose of presenting them in this way at this time, and metadata explaining the circumstances surrounding their collection. After these instructions are given in English, a corresponding Spanish translation is also included. The following fonts are used in this article: in the original Word document from which this file was created, I use the default Times New Roman font for the prose explanations in this introductory section; for all of the phonetically transcribed Chamicuro data forms, on the other hand, I use the Doulos SIL unicode-compliant font. -

Exploring Phonological Areality in the Circum-Andean Region Using a Naive Bayes Classifier

Exploring phonological areality in the circum-Andean region using a naive Bayes classifier Lev Michael, Will Chang, and Tammy Stark December 4, 2013 Abstract This paper describes the Core and Periphery technique, a quantitative method for exploring areality that uses a naive Bayes classifier, a statistical tool for inferring class membership based on training sets assembled from members of those classes. The Core and Periphery technique is applied to the exploration of phonological areality in the Andes and surrounding lowland regions, based on the South American Phonological Inventory database (SAPhon 1.1.3; Michael, Stark, and Chang 2013). Evidence is found for a phonological area centering on the Andean highlands, and extending to parts of the northern and central Andean foothills regions, the Chaco, and Patagonia. Evidence is also found for Southern and North-Central phonological sub-areas within this larger phonological area. Keywords: naive Bayes classifier; linguistic areality; Andean languages; South Ameri- can languages 1 Introduction The goals of this paper are to describe the Core and Periphery technique, an intuitively appealing quantitative method for exploring large linguistic datasets for evidence of linguistic areality, and to illustrate the utility of this technique by applying it to a dataset of South American phonological inventories, focusing on the evidence of phonological areality in the Andes and surrounding lowland areas. Core and Periphery is a method that uses as a starting point linguists' knowledge of the languages and history of a region to generate initial hypotheses regarding `cores': sets of languages that constitute possible linguistic areas (Campbell, Kaufman, and Stark 1986, Thomason 2000, Muysken 2008), or parts of ones. -

Corel Ventura

BIBLIOGRAFA del Instituto Lingstico de Verano en el Per 1946-1999 Page # 1 August 2, 2002 CVP 4.2 KdB BIB-INTR.CHP BIB-INTR.CHP CVP 4.2 KdB Page # 2 August 2, 2002 BIBLIOGRAFA del Instituto Lingstico de Verano en el Per 1946-1999 Recopilacin de Mary Ruth Wise y Anna Louise Shanks INSTITUTO LINGSTICO DE VERANO Lima - 2002 Page # 3 August 2, 2002 CVP 4.2 KdB BIB-INTR.CHP Instituto Lingstico de Verano Javier Prado 200 Magdalena del Mar, Lima o Casilla 2492 Lima 100, Per Primera edicin, 2002 200 ejemplares BIB-INTR.CHP CVP 4.2 KdB Page # 4 August 2, 2002 CONTENIDO PRESENTACIN . 7 PRLOGO . 9 EXPLICACIONES, ABREVIATURAS Y SMBOLOS . 13 PARTE I: PUBLICACIONES Y PONENCIAS . 17 LENGUAS Y CULTURAS AUTCTONAS PERUANAS . 19 LINGSTICA COMPARATIVA . 315 TEMAS GENERALES . 331 PARTE II: MATERIALES INDITOS . 387 PARTE III: NDICES . 541 5 Page # 5 August 2, 2002 CVP 4.2 KdB BIB-INTR.CHP BIB-INTR.CHP CVP 4.2 KdB Page # 6 August 2, 2002 PRESENTACIN Bajo el inocente y parco ttulo de Bibliografa, este volumen ilustra el trabajo de ms de medio siglo (1946–1999) de persistente y particular observar y escuchar a nuestros pueblos amaznicos y andinos. Si solamente librsemos a la imaginacin este largo transcurrir, podramos reconstruir un arduo trajn de investigacin y traduccin. Pero si, ms all de la imaginacin, nos enfrentamos al trabajo concreto que nos ha permitido conocer ahora el lado humano y espiritual (el concreto mundo viviente) de nuestros compatriotas de las zonas amaznicas y andinas, debemos felicitarnos de haber contado con ayuda tan valiosa como la desplegada por los lingistas del ILV. -

Missing Languages

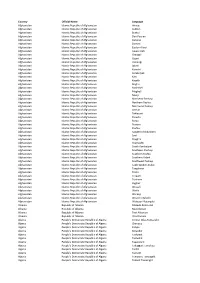

Country Official Name Language Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Aimaq Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ashkun Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Brahui Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Dari Persian Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Darwazi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Domari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Eastern Farsi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gawar-Bati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Grangali Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Gujari Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Hazaragi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Jakati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kamviri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Karakalpak Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kati Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kazakh Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Kirghiz Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Malakhel Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Mogholi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Munji Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northeast Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northern Pashto Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Northwest Pashayi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ormuri Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Pahlavani Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parachi Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Parya Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Prasuni Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan -

The Indigenous Languages of South America WOL 2

The Indigenous Languages of South America WOL 2 Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 The World of Linguistics Editor Hans Henrich Hock Volume 2 De Gruyter Mouton Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 The Indigenous Languages of South America A Comprehensive Guide Edited by Lyle Campbell Vero´nica Grondona De Gruyter Mouton Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3 e-ISBN 978-3-11-025803-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The indigenous languages of South America : a comprehensive guide / edited by Lyle Campbell and Vero´nica Grondona. p. cm. Ϫ (The world of linguistics; 2) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of South America Ϫ Languages. 2. Endangered lan- guages. 3. Language and culture. I. Campbell, Lyle. II. Gron- dona, Vero´nica Marı´a. PM5008.I53 2012 498Ϫdc23 2011042070 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ” 2012 Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Thinkstock/iStockphoto Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ϱ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Bereitgestellt von | Radboud University Nijmegen (Radboud University Nijmegen) Angemeldet | 172.16.1.226 Heruntergeladen am | 06.02.12 13:07 camp_000.pod v 07-10-13 10:05:11 -mu- mu Table of contents Preface Lyle Campbell and Verónica Grondona .................. -

Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison

Language Dynamics and Change 4 (2014) 167–187 brill.com/ldc Some Principles on the Use of Macro-Areas in Typological Comparison Harald Hammarström Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics & Centre for Language Studies, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, The Netherlands [email protected] Mark Donohue Department of Linguistics, Australian National University, Australia [email protected] Abstract While the notion of the ‘area’ or ‘Sprachbund’ has a long history in linguistics, with geographically-defined regions frequently cited as a useful means to explain typolog- ical distributions, the problem of delimiting areas has not been well addressed. Lists of general-purpose, largely independent ‘macro-areas’ (typically continent size) have been proposed as a step to rule out contact as an explanation for various large-scale linguistic phenomena. This squib points out some problems in some of the currently widely-used predetermined areas, those found in the World Atlas of Language Struc- tures (Haspelmath et al., 2005). Instead, we propose a principled division of the world’s landmasses into six macro-areas that arguably have better geographical independence properties. Keywords areality – macro-areas – typology – linguistic area 1 Areas and Areality The investigation of language according to area has a long tradition (dating to at least as early as Hervás y Panduro, 1971 [1799], who draws few historical © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2014 | doi: 10.1163/22105832-00401001 168 hammarström and donohue conclusions, or Kopitar, 1829, who is more interested in historical inference), and is increasingly seen as just as relevant for understanding a language’s history as the investigation of its line of descent, as revealed through the application of the comparative method.