François Bougard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guido M. Berndt the Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy. Some Historical and Archaeological Approaches

The Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy 299 Guido M. Berndt The Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy. Some Historical and Archaeological Approaches Early medieval Europe has often been branded as they have entered upon the sacred soil of Italy, a violent dark age, in which fierce warlords, war- speaks of mere savage delight in bloodshed and riors and warrior-kings played a dominant role in the rudest forms of sensual indulgence; they are the political structuring of societies. Indeed, one the anarchists of the Völkerwanderung, whose de- quite familiar picture is of the early Middle Ages as light is only in destruction, and who seem inca- a period in which armed conflicts and military life pable of culture”.5 This statement was but one in were so much a part of political and cultural devel- a long-lasting debate concerning one particular opment, as well as daily life, that a broad account question that haunted (mainly) Italian historians of the period is to large extent a description of how and antiquarians especially in the nineteenth cen- men went to war.1 Even in phases of peace, the tury – although it had its roots in the fifteenth conduct of warrior-elites set many of the societal century – regarding the role that the Lombards standards. Those who held power in society typi- played in the history of the Italian nation.6 Simply cally carried weapons and had a strong inclination put, the question was whether the Lombards could to settle disputes by violence, creating a martial at- have contributed anything positive to the history mosphere to everyday life in their realms. -

The Builder Magazine October 1921 - Volume VII - Number 10

The Builder Magazine October 1921 - Volume VII - Number 10 Memorials to Great Men Who Were Masons STEPHEN VAN RENSSELAE BY BRO. GEO. W. BAIRD, P.G.M., DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA STEPHEN VAN RENSSELAER, "the first of the Patroons" in the State of New York, was born in the City of New York, and was Grand Master of Masons of that State for four years. We excerpt the following from the History of the Grand Lodge of New York: "Stephen Van Rensselaer, known as the Patroon, an American statesman, and patron of learning, was born in New York, November 1, 1769, the fifth in descent from Killien Van Rensselaer, the original patroon or proprietor of the Dutch Colony of Rensselaerwick, who in 1630, and subsequently, purchased a tract of land near Albany, forty-eight miles long by twenty-four wide, extending over three counties. He was educated at Princeton and Harvard colleges, and married a daughter of General Philip Schuyler, a distinguished officer of the Revolution. Engaging early in politics, at a period when they were the pursuit of men of the highest social position, he was, in 1789, elected to the State Legislature; in 1795, to the State Senate, and became Lieutenant Governor, president of a State convention, and Canal Commissioner. Turning his attention to military affairs, he was, at the beginning of the war of 1812, in command of the State militia, and led the assault of Queenstown; but the refusal of a portion of his troops, from constitutional scruples, to cross the Niagara River, enabled the British to repulse the attack, and the General resigned in disgust. -

König Rothari Begründet Seine Gesetze. Zum Verhältnis Vonkonsens Und Argumentation in Den ›Leges Langobardorum‹*

König Rothari begründet seine Gesetze. Zum Verhältnis vonKonsens und Argumentation in den ›Leges Langobardorum‹* Heinz Holzhauer zugeeignet Christoph H. F. Meyer (Frankfurta.M.) I. Das Langobardenreich: Herrschaftund Religion II. Die ›Leges Langobardorum‹ III. Konsensfähige Aussagen im Recht: Alles nur Propaganda? IV. Beratungs- und Aufzeichnungsvorgänge IV.1 Das Edictum Rothari, Kapitel 386: Konsens, Gemeinwohl, gairethinx IV.2 Die Novellen V. EinzelneStichproben: Konsens und Kontrolle im Edikt VI. Begründungen in der lex scripta VI.1 Historische und sachliche Hintergründe VI.2 Begründungen im EdictumRothari VI.2.a Ein innerweltlicher Maßstab: Vernunftund Unvernunft VI.2.b Religiöse Begründungen: Herzen der Könige, Krankheit als Sündenstrafe und Argumente gegen angeblichen Hexenzauber VII. Schluss: Konsensuale Wege zum geschriebenen Recht *) Zur Entlastung des Anmerkungsapparats wird bei der Zitation vonQuellen des langobardischen Rechts des 7. und 8. Jahrhunderts auf ausführliche bibliographische Angaben verzichtet. Zugrunde liegt stets die kritischeEdition von1868. Vgl. Edictus Langobardorum, hg. vonFriedrich Bluhme (MGH LL 4), Han- nover 1868 (ND Stuttgart/Vaduz 1965), S. 1 225. Die Vorschriften der langobardischen Könige und ben- À eventanischen Duces werden mit Ausnahmedes Edictum Rothari ausschließlich nach den abgekürzten Herrschernamen zitiert: Ed. Ro. (Edictum Rothari), Grim. (Grimoald),Liutpr. (Liutprand), Ra. (Ratchis), Aist. (Aistulf), Areg. (Aregis), Adel. (Adelgis). Die teils Grimoald, teils Liutprandzugeschriebenen soge- nanntenNotitiae werden als »Not.« in Verbindung mit einer Ordnungszahl und Seitenangabe (nach Bluhme)zitiert. Aus Platzgründen werden auch bei der Zitation vonQuellen des justinianischen Rechts Abkürzungen anstelle vollständigerbibliographischer Angaben verwendet. Sie basieren auf den Editionen vonKrüger/Mommsen.Vgl. Corpus iuris civilis, Bd. 1.1:IustinianiInstitutiones, hg. vonPaul Krüger, Berlin 171963; Bd. 1.2: Digesta, hg. vonTheodor Mommsen und Paul Krüger,Berlin 171963; Bd. -

Ablabius, Ablavius 48N36, 50, 51, 59 Aeneas 54N63, 101–2, 106N69

Index The term ‘barbarian’ occurs too frequently in the text to be included comprehensively in this index, and entries are given only for specific topics in relation to discussion ‘barbarians’ not otherwise specified with a particular identity; further entries will be found, again with refer- ence only to specific topics, under the headings of the principal barbarian peoples discussed in this book. Page ranges for chapters devoted to the principal narratives examined above are also not given; rather, I provide only references to particular topics, as readers can easily find the pages devoted to those works by consulting the table of contents. Index entries for a selection of modern scholars whose work has been particularly useful or influential provide references only to explicit discussions of their work or citations of particularly important or influential arguments, not to all citations of their scholarship above. Ablabius, Ablavius 48n36, 50, 51, 59 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (asc) 187, 189, 191, Aeneas 54n63, 101–2, 106n69, 111, 112, 244 214–15, 216n162, 219 Aeneid 46n30, 105n65, 106n69, 110, 160n51, Anglo-Saxons: 166, 174, 178 conversion of 186, 188 Agilulf 120, 121, 137, 141–2, 143, 145n115, in the Historia Brittonum 188–9, 216 145n118, 146, 186n7 migration of to England 15n35, 184–7, Alahis 145n118 188, 189, 190, 216, 217, 255 Alboin (Lombard ruler) 119n15, 120, 121, oral traditions among 186–7, 191–2, 206, 123, 124, 128–9, 129–40, 143–4, 213n149, 216, 225–7, 230–1, 234 146, 149 paganism among 186, 188n13, 216 grave and sword of 139n94 -

Writers and Re-Writers of First Millennium History

Writers and Re-Writers of First Millennium History Trevor Palmer Society for Interdisciplinary Studies 1 Writers and Re-Writers of First Millennium History Trevor Palmer This is essentially a revised and expanded version of an article entitled ‘The Writings of the Historians of the Roman and Early Medieval Periods and their Relevance to the Chronology of the First Millennium AD’, published in five instalments in Chronology & Catastrophism Review 2015:3, pp. 23-35; 2016:1, pp. 11-19; 2016:2, pp. 28-35; 2016:3, pp. 24-32; 2017:1, pp. 19-28. It also includes a chapter on an additional topic (the Popes of Rome), plus appendices and indexes. Published in the UK in November 2019 by the Society for Interdisciplinary Studies © Copyright Trevor Palmer, 2019 Front Cover Illustrations. Top left: Arch of Constantine, Rome. Top right: Hagia Sophia, Istanbul (originally Cathedral of St Sophia, Constantinople); Bottom left: Córdoba, Spain, viewed over the Roman Bridge crossing the Guadalquivir River. Bottom right: Royal Anglo- Saxon burial mound at Sutton Hoo, East Anglia. All photographs in this book were taken by the author or by his wife, Jan Palmer. 2 Contents Chapter 1: Preliminary Considerations …………………………………………………………… 4 1.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 1.2 Revisionist and Conventional Chronologies …………………………………………………………. 5 1.3 Dating Systems ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.4 History and Religion ………………………………………………………………………………….13 1.5 Comments on Topics Considered in Chapter 1 ………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Roman and Byzantine Emperors ……………………………………………………. 17 2.1 Roman Emperors ……………………………………………………………………………………... 17 2.1.1 The Early Roman Empire from Augustus to Septimius Severus ………………………………. 17 2.1.2 Emperors from Septimius Severus to Maurice …………………………………………………. -

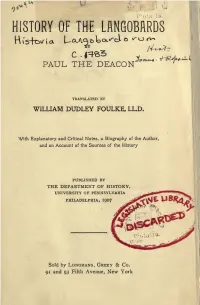

HISTORY of the LANGOBARDS a Bcx^D O ""0 I^

U : . v. HISTORY OF THE LANGOBARDS a bcx^d o ""0 i^ C . PAUL THE DEACON' TRANSLATED BY WILLIAM DUDLEY FOULKE, LL.D. With Explanatory and Critical Notes, a Biography of the Author, and an Account of the Sources of the History PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY. UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PHILADELPHIA, IQO7 Sold by LONGMANS, GREEN & Co. 91 and 93 Fifth Avenue, New York COPYRIGHT, 1906, BY WILLIAM DUDLEY FOULKE. 5 PREFACE. MOMMSEN declares that Paul the Deacon's history of Italy, from the foundation of Rome to the beginning of the time of the Carlovingians, is properly the step- ping-stone from the culture of the ancient to that of the modern world, marking the transition and connecting the their immi- both together ; that Langobards upon gration into Italy not only exchanged their own lan- guage for that of their new home, but also adopted the traditions and early history of Rome without, however, their that it is in this fact abandoning own ; good part which put the culture of the modern world upon the it that no one has felt this road on which moves to-day ; in a more living manner than Paul, and that no one has contributed so much through his writings to secure for the world the possession of Roman and Germanic tra- dition by an equal title as did this Benedictine monk when, after the overthrow of his ancestral kingdom, he 1 wrote its history as part of the history of Italy. Whatever therefore were his limitations as an author, the writings of Paul the Deacon mark an epoch. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations ARF Annales Regni Francorum (see Bibliography) ARF Rev refers to the revised version of c. 814 CC Corpus Christianorum, series latina CFHB Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae CHFM Les Classiques de l'Histoire de France au MlQ'en Age CLA Codices Latini Antiquiores, ed. E. A. Lowe, XI vols plus a Supplement (Oxford, 1934-71) CSEL Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum CSHB Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae FEHL Coleccion Fuentes y Estudios de Historia Leonesa Fontes Fontes ad Historiam Regni FrancorumAevi Karolini IIIustrandam, ed. R. Rau (3 vols, Dannstadt, 1955-60) MGH Monumenta Germaniae Historica, subdivided by series: AA Audores Antiquissimi Cap;t Cap;tularia Epp Epistulae LL Leges SS Scnptores SRG Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum SRM Scriptores Rerum Meruvingicarum MloG Miueilungen des Instituts for osterreichische Geschichtsforschung PG Patrologia Graeca, ed. J. P. Migne PL Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne PLRE Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, ed. J. R. Martindale et al. 2 vols: vol. I: AD 260-395 (Cambridge, 1971) vol. II: AD 395-527 (Cambridge, 1980) RIC Roman Imperial Coinage SC Sources Chritiennes SHF Societe de l'Histoire de France SLH Scriptores Latini Hiberniae 356 Notes 1 PROBLEM-SOLVING EMPERORS 1. Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, XXIII. v. 17; F. Millar, The Roman Empire and its Neighbours (London and New York, 1967), pp. 238-48. 2. A. A. Barrett, Caligula: the Corruption ofPower (London, 1990), pp. xix, 1- 41,172-80. 3. Herodian, Basileas Historias, VI. viii.i and VII. i.l-2. 4. Scriptores Historiae Augustae: Maximini Duo (ascribed to Julius Capitol inus), I. 5-7, and 11.5; see also the discussion in R. -

Gender and Historiography Studies in the Earlier Middle Ages in Honour of Pauline Stafford

Gender and historiography Studies in the earlier middle ages in honour of Pauline Stafford Edited by Janet L. Nelson, Susan Reynolds and Susan M. Johns Professor Pauline Stafford Gender and historiography Studies in the earlier middle ages in honour of Pauline Stafford Gender and historiography Studies in the earlier middle ages in honour of Pauline Stafford Edited by Janet L. Nelson, Susan Reynolds and Susan M. Johns LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2012. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 46 9 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 79 7 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors ix List of abbreviations xi List of figures xiii Introduction 1 1. Fatherhood in late Lombard Italy Ross Balzaretti 9 2. Anger, emotion and a biography of William the Conqueror David Bates 21 3. ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle(s)’ or ‘Old English Royal Annals’? Nicholas Brooks 35 4. The tale of Queen Ælfthryth in William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum Kirsten A. Fenton 49 5. Women, children and the profits of war John Gillingham 61 6. Charters, ritual and late tenth-century English kingship Charles Insley 75 7. Nest of Deheubarth: reading female power in the historiography of Wales Susan M. -

The Lombard Past in Post-Conquest Italian Historiography Eduardo Fabbro

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 05:33 Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Charlemagne and the Lombard Kingdom That Was: the Lombard Past in Post-Conquest Italian Historiography Eduardo Fabbro Volume 25, numéro 2, 2014 Résumé de l'article Avant la conquête carolingienne de la Lombardie en Italie (774), l’Église a URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1032839ar déployé de grands efforts auprès de la cour franque pour la convaincre de la DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1032839ar légitimité de l’invasion. En empruntant les termes de Grégoire Ier, la cour pontificale trace un portrait offensant des Lombards, les dépeignant comme Aller au sommaire du numéro étant traîtres, exécrables et sauvages. Le présent article analyse l’épistolaire papal du VIIIe siècle et le Liber Pontificalis afin d’établir les stratégies derrière cette campagne. Ensuite, il se penche sur la réaction des Lombards après la Éditeur(s) conquête et s’attarde aux efforts de Paul Diacre et de l’auteur anonyme de l’Origo Langobardorum codicis Gothanis pour remettre en question le portrait The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada des Lombards dressé par la cour pontificale et pour se réapproprier le passé chrétien de leur peuple. Tant Paul que l’Origo de Gotha ont mis l’accent sur ISSN l’importance de la conversion – et surtout du rôle de Grégoire le Grand – dans la réhabilitation des Lombards. Cet article avance que leurs travaux 0847-4478 (imprimé) constituent une tentative des Lombards de dissocier leur foi chrétienne de la 1712-6274 (numérique) conquête et de se réapproprier le récit de leur propre passé. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations ARF Annates Regni Francorum (see Bibliography); ARF Rev refers to the revised version of c. 814 cc Corpus Christianorum, series latina CFHB Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae CHFM Les Classiques de l'Histoire de France au Moyen Age CIA Codices Latini Antiquiores, ed. E. A. Lowe, 9 vols plus a Supplement (Oxford, 1934-71) CSEL Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum CSHB Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae FEHL Colecci6n Fuentes y Estudios de Historia Leonesa Fontes Fontes ad Historiam Regni Francorum Aevi Karolini Illus trandam, ed. R. Rau (3 vols, Darmstadt, 1955-60) MGH Monumenta Germaniae Historica, subdivided by series: AA Auctores Antiquissimi Capit Capitularia Epp Epistulae LL Leges SS Scriptores SRG Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum SRM Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum MIOG Mitteilungen des Instituts for osterreichische Geschichtsforschung PG Patrologia Graeca, ed. J. P. Migne PL Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne PLRE Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, ed. J. R. Martindale et al., 3 vols: vol. 1: AD 260-395 (Cambridge, 1971) vol. II: AD 395-527 (Cambridge, 1980) vol. III: AD 527-641 (Cambridge, 1992) RIC Roman Imperial Coinage sc Sources Chretiennes SHF Societe de l'Histoire de France SLH Scriptores Latini Hiberniae 423 Notes 1 PROBLEM-SOLVING EMPERORS 1. Arnmianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, XXIII. v. 17; F. Millar, The Roman Empire and its Neighbours (London and New York, 1967), pp. 238-48. 2. A. A. Barrett, Caligula: the Corruption of Power (London, 1990), pp. xix, 1-41, 172-80. 3. Herodian, Basileas Historias, VI. viii. i and VII. i. 1-2. 4. Scriptores Historiae Augustae: Maximini Duo (ascribed to Julius Capi tolinus), I. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Land and Landscape: The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Land and Landscape: The Transition from Agilolfing to Carolingian Bavaria, 700-900 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Leanne Marie Good 2012 © Copyright by Leanne Marie Good 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Land and Landscape: The Transition from Agilolfing to Carolingian Bavaria, 700-900 by Leanne Marie Good Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Patrick Geary, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of the political, social, cultural and physical landscape of eighth-century Bavaria as this region was absorbed into the expanding Frankish kingdom, following the deposition of its quasi-regal duke, Tassilo, in 788. My study aims to elucidate the wider process by which the Carolingian dynasty united most of Western Europe under its control in the course of a few decades. It is my contention that changes made during this period to the organization of agricultural land and ecclesiastical jurisdictions - the physical use of land resources, and their mental demarcations - changed perceptions of identity and supported changes in rulership. ii At the beginning of the eighth century, the family referred to by historians as the Arnulfings or Pippinids, increased their power greatly through a variety of strategems (the term Carolingian, from the name of its most famous scion, is often projected back). This family controlled the office of Mayor of the Palace to the Merovingian kings; in that role, Charles Martel essentially functioned as the political leader of the Franks. His son Pippin inherited the office, and took the title of King of the Franks, as well, which threatened the balance of aristocratic power in the kingdom and the peripheral duchies. -

1 the Problem with Michael 1

NOTES 1 The Problem with Michael 1 . Bernardus monachus francus, Itinerarium 18, PL 121.574; F. Avril and J.-R. Gaborit discuss the pilgrimage, “L’Itinerarium Bernardi monachi et les pèlerinages d’Italie du Sud pendant le Haut-Moyen-Âge,” M é langes d’arch é ologie et d’histoire 79 (1967): 269–298. The hagiographical Revelatio ecclesiae de sancti Michaelis details the foundation of Mont Saint-Michel by St. Aubert of Avranches, Revelatio ecclesiae sancti Michaelis archangeli in Monte qui dicitur Tumba V, edited by Pierre Bouet and Olivier Desbordes, Chroniques latines du Mont Saint-Michel (IXe–XIIe si è cle), vol. 1 (Caen: Presses universitaires de Caen, 2009), pp. 98–99. All Latin citations are from Bouet’s edition. Mabillon’s edition is published as Apparitio de Sancti Michaelis in Monte Tumba , AASS, September 8.76–79, which John Charles Arnold translates into English: “The ‘Revelatio Ecclesiae de Sancti Michaelis’ and the Mediterranean Origins of Mont St.-Michel,” The Heroic Age 10 (May 2007), http://www.mun.ca/mst/heroicage/issues/10/arnold. html . All English citations are from that publication. The Bayeux Tapestry famously depicts Harold Godwinson pulling soldiers from quicksand with Mont Saint-Michel in the background. The Museum of Reading has placed online images from its nineteenth- century copy of the tapestry, with that of Harold’s exploits found at http://www.bayeuxtapestry.org.uk/ Bayeux8.htm . 2 . For the most recent analysis of Notre-Dame-sous-Terre, see Christian Sapin, Maylis Bayl é et al., “Arch é ologie du b â ti et arch é om é trie au Mont- Saint-Michel, nouvelles approches de Notre-Dame-sous-Terre,” Arch é ologie m é di é vale 38 (2008): 71–122 and 94 and 97 for the mortar of the “cyclo- pean” wall.