Constructing Identity in Lombard Italy Giulia Vollono

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

The World's Saga

Hugvísindasvið The World's Saga An English Translation of the Old Norse Veraldar saga, a History of the World in Six Ages Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs James Andrew Cross Ágúst 2012 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies The World's Saga An English Translation of the Old Norse Veraldar saga, a History of the World in Six Ages Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs James Andrew Cross Kt.: 030785-4449 Leiðbeinandur: Svanhildur Óskarsdóttir og Torfi H. Tulinius Ágúst 2012 Table of Contents 1. Introduction . i 1.1 Defining Veraldar saga . i 1.2 Sources of Veraldar saga . i 1.3 Historiographic Contexts . iv 1.4 The Manuscripts . viii 1.5 Notes on Translation and Annotation . x 2. Text . 1 2.1 [The First Age] (Creation to Noah's Ark) . 1 2.2 The Second Age (Entering the Ark to Life of Terah, Abraham's Father) . 5 2.3 The Third Age (Life of Abraham to Reign of King Saul) . 7 2.3.1 Regarding Joseph and His Brothers . 11 2.3.2 Miraculum . 13 2.3.3 Regarding Judges . 13 2.4 [The Fourth Age] (Reign of King David to Life of Elisha) . 14 2.5 The Fifth Age (Babylonian Captivity to Reign of Emperor Augustus) . 17 2.5.1 Regarding Kings . 19 2.5.2 Regarding Idols . 19 2.5.3 Regarding Mattathias et Filii Eius . 20 2.6 The Sixth Age (Birth of Christ to Reign of Emperor Frederick I) . 23 2.6.1 De Tiberio . 23 3. Bibliography . 35 Introduction Defining Veraldar saga Veraldar saga is a medieval Icelandic prose universal history written in the Old Norse vernacular.1 It describes the history of the world divided into six “ages” from the Biblical creation narrative until the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. -

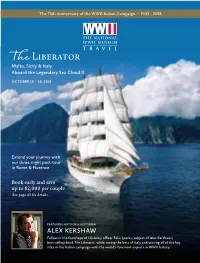

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams. Futhark 3

Futhark International Journal of Runic Studies Main editors James E. Knirk and Henrik Williams Assistant editor Marco Bianchi Vol. 3 · 2012 © Contributing authors 2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ All articles are available free of charge at http://www.futhark-journal.com A printed version of the issue can be ordered through http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-194111 Editorial advisory board: Michael P. Barnes (University College London), Klaus Düwel (University of Göttingen), Lena Peterson (Uppsala University), Marie Stoklund (National Museum, Copenhagen) Typeset with Linux Libertine by Marco Bianchi University of Oslo Uppsala University ISSN 1892-0950 Bracteates and Runes Review article by Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams Die Goldbrakteaten der Völkerwanderungszeit — Auswertung und Neufunde. Eds. Wilhelm Heizmann and Morten Axboe. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 40. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. 1024 pp., 102 plates. ISBN 978-3-11-022411-5, e-ISBN 978-3-11-022411-2, ISSN 1866-7678. 199.95 €, $280. From the Migration Period we now have more than a thousand stamped gold pendants known as bracteates. They have fascinated scholars since the late seventeenth century and continue to do so today. Although bracteates are fundamental sources for the art history of the period, and important archae- o logical artifacts, for runologists their inscriptions have played a minor role in comparison with other older-futhark texts. It is to be hoped that this will now change, however. -

Guido M. Berndt the Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy. Some Historical and Archaeological Approaches

The Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy 299 Guido M. Berndt The Armament of Lombard Warriors in Italy. Some Historical and Archaeological Approaches Early medieval Europe has often been branded as they have entered upon the sacred soil of Italy, a violent dark age, in which fierce warlords, war- speaks of mere savage delight in bloodshed and riors and warrior-kings played a dominant role in the rudest forms of sensual indulgence; they are the political structuring of societies. Indeed, one the anarchists of the Völkerwanderung, whose de- quite familiar picture is of the early Middle Ages as light is only in destruction, and who seem inca- a period in which armed conflicts and military life pable of culture”.5 This statement was but one in were so much a part of political and cultural devel- a long-lasting debate concerning one particular opment, as well as daily life, that a broad account question that haunted (mainly) Italian historians of the period is to large extent a description of how and antiquarians especially in the nineteenth cen- men went to war.1 Even in phases of peace, the tury – although it had its roots in the fifteenth conduct of warrior-elites set many of the societal century – regarding the role that the Lombards standards. Those who held power in society typi- played in the history of the Italian nation.6 Simply cally carried weapons and had a strong inclination put, the question was whether the Lombards could to settle disputes by violence, creating a martial at- have contributed anything positive to the history mosphere to everyday life in their realms. -

The Builder Magazine October 1921 - Volume VII - Number 10

The Builder Magazine October 1921 - Volume VII - Number 10 Memorials to Great Men Who Were Masons STEPHEN VAN RENSSELAE BY BRO. GEO. W. BAIRD, P.G.M., DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA STEPHEN VAN RENSSELAER, "the first of the Patroons" in the State of New York, was born in the City of New York, and was Grand Master of Masons of that State for four years. We excerpt the following from the History of the Grand Lodge of New York: "Stephen Van Rensselaer, known as the Patroon, an American statesman, and patron of learning, was born in New York, November 1, 1769, the fifth in descent from Killien Van Rensselaer, the original patroon or proprietor of the Dutch Colony of Rensselaerwick, who in 1630, and subsequently, purchased a tract of land near Albany, forty-eight miles long by twenty-four wide, extending over three counties. He was educated at Princeton and Harvard colleges, and married a daughter of General Philip Schuyler, a distinguished officer of the Revolution. Engaging early in politics, at a period when they were the pursuit of men of the highest social position, he was, in 1789, elected to the State Legislature; in 1795, to the State Senate, and became Lieutenant Governor, president of a State convention, and Canal Commissioner. Turning his attention to military affairs, he was, at the beginning of the war of 1812, in command of the State militia, and led the assault of Queenstown; but the refusal of a portion of his troops, from constitutional scruples, to cross the Niagara River, enabled the British to repulse the attack, and the General resigned in disgust. -

CLASS DISTINCTIONS in EIGHTH CENTURY ITALYQ TALY in The

CLASS DISTINCTIONS IN EIGHTH CENTURY ITALYQ I TALY in the eighth century was dominated by the Lombards, whose kingdom centered in the Po Valley around their capital city of Pavia. But although the Lom- bards in the eighth century were the most important single political element in the peninsula, they were never the only power. The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire continued to control a small area around the old Roman city of Ra- venna, and in addition, the Byzantines continued to control small amounts of territory in the extreme southern part of Italy. These Byzantine territories were a holdover from the Italian conquests made under the East Roman Emperor Justinian in the middle of the sixth century. In the center of the Italian peninsula and to a certain extent threatening to cut the Lombard power in two, was the territory which was under the nominal control of a shadowy official called the Duke of Rome but which was for all practical purposes under the control of the Bishop of Rome, an individual anxious to increase his power and the prestige of his see. In discussing class distinctions in eighth century Italy, we shall here be concerned primarily with the dominant people of this period, the Lombards, although in discussing the various classes of society among this people it will be necessary to note from time to time the relative position of other non-Lombard persons in the peninsula. The Lombards were a tribe of Germanic barbarians who * A public lecture delivered at the Rice Institute on October 28, 1951. -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release. -

König Rothari Begründet Seine Gesetze. Zum Verhältnis Vonkonsens Und Argumentation in Den ›Leges Langobardorum‹*

König Rothari begründet seine Gesetze. Zum Verhältnis vonKonsens und Argumentation in den ›Leges Langobardorum‹* Heinz Holzhauer zugeeignet Christoph H. F. Meyer (Frankfurta.M.) I. Das Langobardenreich: Herrschaftund Religion II. Die ›Leges Langobardorum‹ III. Konsensfähige Aussagen im Recht: Alles nur Propaganda? IV. Beratungs- und Aufzeichnungsvorgänge IV.1 Das Edictum Rothari, Kapitel 386: Konsens, Gemeinwohl, gairethinx IV.2 Die Novellen V. EinzelneStichproben: Konsens und Kontrolle im Edikt VI. Begründungen in der lex scripta VI.1 Historische und sachliche Hintergründe VI.2 Begründungen im EdictumRothari VI.2.a Ein innerweltlicher Maßstab: Vernunftund Unvernunft VI.2.b Religiöse Begründungen: Herzen der Könige, Krankheit als Sündenstrafe und Argumente gegen angeblichen Hexenzauber VII. Schluss: Konsensuale Wege zum geschriebenen Recht *) Zur Entlastung des Anmerkungsapparats wird bei der Zitation vonQuellen des langobardischen Rechts des 7. und 8. Jahrhunderts auf ausführliche bibliographische Angaben verzichtet. Zugrunde liegt stets die kritischeEdition von1868. Vgl. Edictus Langobardorum, hg. vonFriedrich Bluhme (MGH LL 4), Han- nover 1868 (ND Stuttgart/Vaduz 1965), S. 1 225. Die Vorschriften der langobardischen Könige und ben- À eventanischen Duces werden mit Ausnahmedes Edictum Rothari ausschließlich nach den abgekürzten Herrschernamen zitiert: Ed. Ro. (Edictum Rothari), Grim. (Grimoald),Liutpr. (Liutprand), Ra. (Ratchis), Aist. (Aistulf), Areg. (Aregis), Adel. (Adelgis). Die teils Grimoald, teils Liutprandzugeschriebenen soge- nanntenNotitiae werden als »Not.« in Verbindung mit einer Ordnungszahl und Seitenangabe (nach Bluhme)zitiert. Aus Platzgründen werden auch bei der Zitation vonQuellen des justinianischen Rechts Abkürzungen anstelle vollständigerbibliographischer Angaben verwendet. Sie basieren auf den Editionen vonKrüger/Mommsen.Vgl. Corpus iuris civilis, Bd. 1.1:IustinianiInstitutiones, hg. vonPaul Krüger, Berlin 171963; Bd. 1.2: Digesta, hg. vonTheodor Mommsen und Paul Krüger,Berlin 171963; Bd. -

Le Pouvoir Des Reines Lombardes Magali Coumert

Le pouvoir des reines lombardes Magali Coumert To cite this version: Magali Coumert. Le pouvoir des reines lombardes. Femmes de pouvoir et pouvoir des femmes dans l’Europe occidentale médiévale et moderne, Apr 2006, Valenciennes, France. p. 379-397. hal- 00967401 HAL Id: hal-00967401 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00967401 Submitted on 3 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Le pouvoir des reines lombardes Magali Coumert « La reine Gondeberge, vu que tous les Lombards lui avaient prêté serment de fidélité, ordonna à Rothari, un des ducs, du territoire de Brescia, de venir la trouver. Elle le poussa à abandonner l’épouse qu’il avait et à la prendre en mariage : grâce à elle, tous les Lombards l’élèveraient sur le trône »1. Suivant ce passage de la Chronique de Frédégaire, le roi lombard Rothari tenait le pouvoir royal de sa femme, à qui les Lombards avaient juré fidélité. Gondeberge, fille du roi Agilulf, sœur du roi évincé Adaloald, et suivant la Chronique, femme de ses successeurs rivaux Arioald puis Rothari2, était une clef de l’accès au pouvoir royal. -

Looking at the Edict of Rothari Between German Ancestral Customs and Roman Legal Traditions

LUCA LOSCHIAVO* LOOKING AT THE EDICT OF ROTHARI BETWEEN GERMAN ANCESTRAL CUSTOMS AND ROMAN LEGAL TRADITIONS ABSTRACT. The essay takes up the debate on the nature of the most ancient Lombard legislation (whether it is really ‘Germanic’ or influenced by the Roman legal tradition). After more than two hundred years of discussion, a satisfactory solution is still waiting to be found. The research of the last decades on the early medieval Europe has deeply changed the perspective from which to look at the ancient norms. Legal historiography can no longer ignore the contribution of the studies of ethnogenesis and not even how much we know about the complex phenomenon of vulgar Roman law. Through some examples especially related to criminal law and the trial, these pages intend to show how useful it is to address the subject according to a different approach. Particurarly strong seems to be the imprint of the late Roman military law on the Longobard legislature. CONTENT. 1. Framing Lombard law – 2. Re-starting the debate – 3. The mystery of the gairethinx – 4. New (and old) risks – 5. Ancient customs and complex ethnogenesis – 6. In- stitutions and criminal law – 7. Excursus: Roman military justice and ‘German’ judges – 8. ‘Germanic’ procedures: a new approach – 9. Lombard legal procedure – 10. Traditional proofs and evidence of witnesses in the Edict of Rothari 1. Framing Lombard law How far do Lombard laws – and especially the Edict of Rothari – reflect the ancestral customs of that Germanic people and how far do they reveal, on the contrary, the influence of Roman legal traditions? This question is a ‘classic’ theme of debate for legal historians (in Germany and Italy in particular).