Adultery As a Bar to Dower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohabitation at Both Sides of the Atlantic Jenny De Jong

Symposium: Cohabitation at both sides of the Atlantic The Role of Children and Stepchildren in Divorced or Widowed Parents’ Decision-Making about Cohabitation After Repartnering: A Qualitative Study Jenny de Jong Gierveld, Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague and VU University Amsterdam Eva-Maria Merz, Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION Longevity and higher divorce rates trends have led to a growing number of older adults who repartner after a breakup or the death of a spouse. Divorced or widowed adults have lost an important source of social support and daily companionship but can and often do remedy this absence of a significant other by establishing a new romantic bond (Carr, 2004). Divorced and widowed men in particular report an interest in getting remarried or living together (Moorman, Booth, & Fingerman, 2006). Many older adults are successful in finding a new partner; some remarry, others cohabit, and some start Living-Apart-Together (LAT) relationships. Repartnering at an older age and living arrangements such as remarriage and cohabitation or LAT have already been the topic of ample research (e.g. De Jong Gierveld, 2002, 2004; Karlsson & Borell, 2002; Régnier-Loilier, Beaujouan, & Villeneuve-Gokalp, 2009). Studies have also been conducted on the role children and stepchildren might play in influencing their parents’ decision whether to move in together (e.g., Graefe & Lichter, 1999; Goldscheider & Sassler, 2006), but are still rather scarce, especially regarding middle-aged and older parents. This is unfortunate because parents remain parents for a lifetime and it seems more than likely that regardless of whether they still live at home, children play an important role in the decision-making about the new family constellation. -

Turn Mourning Into Dancing! a Policy Statement on Healing Domestic Violence

TURN MOURNING INTO DANCING! A POLICY STATEMENT ON HEALING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE and STUDY GUIDE Approved By The 213th General Assembly (2001) Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Developed By The Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy of the General Assembly Council This document may be viewed on the World Wide Web at http://www.pcusa.org/oga/publications/dancing.pdf Published By The Office of the General Assembly 100 Witherspoon Street Louisville, KY 40202-1396 Copyright © 2001 The Office of the General Assembly Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Printed in the United States of America Cover design by the Office of the General Assembly, Department of Communication and Technology No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (brief quotations used in magazine or newspaper reviews excepted), without the prior permission of the publisher. The sessions, presbyteries, and synods of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) may use sections of this publication without receiving prior written permission of the publisher. Copies are available from Presbyterian Distribution Services (PDS) 100 Witherspoon Street Louisville, KY 40202-1396, By calling 1-800-524-2612 (PDS) Please specify PDS order # OGA-01-018. September 2001 To: Stated Clerks of the Middle Governing Bodies, Middle Governing Body Resource Centers, Clerks of Sessions, and the Libraries of the Theological Seminaries Dear Friends: The 213th General Assembly (2001) -

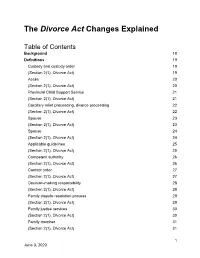

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Theological Reflections on Sex As a Cleansing Ritual for African Widows

Theological Reflections on Sex as a Cleansing Ritual for African Widows Elijah M. Baloyi Abstract Violence against women is deeply rooted in human history. The patriarchal gender inequalities, culture, religion and tradition have been vehicles by means of which these structured stereotypes were entrenched. In trying to keep the widow in the family as well as forcing her to prove her innocence, certain rituals were introduced, one of them being the sex cleansing ritual. Besides being both oppressive and abusive, the sex cleansing ritual can also be an instrument of sex-related sicknesses such as HIV and AIDS. Although some widows are willing to undergo this ritual, others succumb because they fear dispossession or expulsion from home, thereby forfeiting the right to inherit their late husbands’ possessions. It is the aim of this study to unveil by way of research how African widows are subjected to this extremely abusive ritual and exposed to HIV and AIDS. Their vulnerability will be examined from a theological point of view and guidelines will be given. The article will highlight how humiliating and unchristian such a ritual is for defenceless widows and their children. Keywords: Sex cleansing, ritual, widow, inheritance, sex cleansers, oppression. Introduction According to Afoloyan (2004:185), it is widely believed amongst Africans that the demise of a husband does not mean the end of a marriage. The author intends to introduce the problem at hand with a quotation from LeFraniere (2005: 1) which states: Alternation 23,2 (2016) 201 – 216 201 ISSN 1023-1757 Elijah M. Baloyi I cried, remembering my husband. -

Untying the Knot: an Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Common Law Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation Danaya C. Wright, Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866, 38 U. Rich. L. Rev. 903 (2004), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNTYING THE KNOT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENGLISH DIVORCE AND MATRIMONIAL CAUSES COURT RECORDS, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright * I. INTRODUCTION Historians of Anglo-American family law consider 1857 as a turning point in the development of modern family law and the first big step in the breakdown of coverture' and the recognition of women's legal rights.2 In 1857, The United Kingdom Parlia- * Associate Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law. This arti- cle is a continuation of my research into nineteenth-century English family law reform. My research at the Public Record Office was made possible by generous grants from the University of Florida, Levin College of Law. -

Living Apart Together in Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Duncan, Simon, Phillips, Miranda, Carter, Julia, Roseneil, Sasha and Stoilova, Mariya. Title: Practices and perceptions of living apart together Publication year: 2014 Journal title: Family Science Publisher: Routledge Link to publisher’s site: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rfsc20/current#.UynEL6h_vTo Citation: Duncan, S., Phillips, M., Carter, J., Roseneil, S. and Stoilova, M. (2014). Practices and perceptions of living apart together. Family Science. [Awaiting publication, Mar 2014]. Copyright statement: © 2014, Taylor and Francis. This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article to be published in Family Science, 2014. Copyright Taylor & Francis. Available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rfsc20/current#.UynEL6h_vTo Practices and perceptions of living apart together Forthcoming in Family Science Simon Duncan*, Miranda Phillips**, Julia Carter***, Sasha Roseneil+, Mariya Stoilova+ * University of Bradford ** National Centre for Social Research, UK *** Canterbury Christchurch University + Birkbeck College, University of London Corresponding Author: Simon Duncan, CASR, Ashfield Bldg, Bradford BD7 1DP [email protected] 1 2 Abstract This paper examines how people living apart together (LATs) maintain their relationships, and describes how they view this living arrangement. -

What Does the Bible Say About Divorce and Remarriage

WHAT DOES THE BIBLE SAY ABOUT DIVORCE AND REMARRIAGE? “If your opinion about anything contradicts God’s Word, guess which one is wrong?” Rick Warren “There is a way that seems right to a man, but its end is the way to death.” (Proverbs 14:12 ESV) What does the Bible say about marriage? Marriage is created by God as lifelong institution between a man and a woman, rooted in creation, with a significance that shows in its comparison to Christ’s relationship with the church (Ephesians 5:22-33). Today marriage is often defined by the emerging trends, understandings, feelings, and opinions of the culture rather than the transcendent, immutable, and eternal truth found described by the God who created it. This change in understanding and practice has led to an overwhelming amount of marriages ending in divorce and resulting in remarriage. Although many sociological, psychological, economic, emotional, and man- centered rationales may be created to explain and justify the practice of divorce and remarriage, the Christian perspective and practice must be rooted in a balanced and holistic application of biblical theology. The overwhelming practice in today’s churches is to allow remarriage in most cases of legal divorce. This is problematic in a society that frequently allows no-fault divorce, thus eliminating most standards or requirements for divorce. In the few churches that do choose to discriminate in the practice of remarriage, it is often confusing and complex to determine accurately the circumstances surrounding the divorce as well as the guilt or innocence of each party involved. In evaluating the Scriptural texts in regard to marriage, divorce, and remarriage the Bible points to the marriage bond as ending only in death, not merely being severed by legal divorce, thereby prohibiting remarriage following divorce no matter the circumstance (Matthew 19:6, Romans 7:1-3, 1 Corinthians 7:10-11,39). -

Couples Living Apart Marital Status Together.” International Review of Soci- Ology 11, 1: 39-46

CouplesCouples livingliving apartapart by Anne Milan and Alice Peters ost people want to share an intimate connection arrangement was not ideal and was only temporary.1 In with another person but the framework within today’s society, unmarried couples who live in separate M which relationships occur has changed dramati- residences while maintaining an intimate relationship cally. Traditionally, marriage was the only acceptable social are referred to as non-resident partners or “living apart institution for couples. In recent decades, however, people together” (LAT) couples. This type of relationship may have been marrying at increasingly older ages, divorce and be seen as part of the “going steady” process, often as a separation rates have grown, and living together without prelude to a common-law union or marriage. Alterna- marriage has become more common. Now it is not tively, LAT unions may be viewed as a more permanent unusual for relationships to form and dissolve and new partnerships to be created over the course of the life cycle. Previously, social norms prescribed that a couple should marry and live in the same household. When a couple 1. Levin, I. and J. Trost. 1999. “Living apart together.” Commu- could not live together, it was assumed that the living nity, Work and Family 2, 3: 279-94. 2 CANADIAN SOCIAL TRENDS SUMMER 2003 Statistics Canada — Catalogue No. 11-008 living arrangement by individuals who do not want, or are not able, to What you should know about this study share a home. This article uses data CST from the 2001 General Social Survey to examine the characteristics of indi- Data in this article come from the 2001 General Social Survey. -

Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: a Statute to End the Tug-Of-War?

Washington University Law Review Volume 67 Issue 3 Symposium on the State Action Doctrine of Shelley v. Kraemer 1989 Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: A Statute to End the Tug-of-War? C. Gail Vasterling Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation C. Gail Vasterling, Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: A Statute to End the Tug-of-War?, 67 WASH. U. L. Q. 923 (1989). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol67/iss3/15 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHILD CUSTODY MODIFICATION UNDER THE UNIFORM MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE ACT: A STATUTE TO END THE TUG-OF-WAR? Each year approximately one million American children experience the trauma of their parents' divorces.1 The resulting child custody deci- sions involve familial complications and difficulties requiring judicial dis- cretion.' The amount of discretion trial court judges currently exercise, however, often yields unpredictable and poorly reasoned decisions. Fre- quently, the trial court judge's decision motivates the losing parent to relitigate.3 In an effort to ensure greater stability after the initial custody decision and to dissuade further litigation, the drafters of the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act (UMDA)4 provided a variety of procedural and substantive limitations on a judge's ability to grant changes in custody.5 This Note evaluates the UMDA's custody modification provisions and explores their application by the courts. -

Opinion, Ross Stanley V. Carolyn Haynes Stanley, No. 13-0960

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA January 2014 Term _______________ FILED May 27, 2014 No. 13-0960 released at 3:00 p.m. RORY L. PERRY II, CLERK _______________ SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA ROSS STANLEY, Petitioner Below, Petitioner v. CAROLYN HAYNES STANLEY, Respondent Below, Respondent ____________________________________________________________ Appeal from the Circuit Court of Greenbrier County The Honorable Joseph C. Pomponio, Jr., Judge Civil Action No. 12-D-65 REVERSED ____________________________________________________________ Submitted: May 6, 2014 Filed: May 27, 2014 Martha J. Fleshman, Esq. J. Michael Anderson, Esq. Fleshman Law Office Rainelle, West Virginia Lewisburg, West Virginia Counsel for the Respondent Counsel for the Petitioner JUSTICE KETCHUM delivered the Opinion of the Court. SYLLABUS BY THE COURT 1. W.Va. Code § 43-1-2(b) [1992] requires any married person who conveys an interest in real estate to notify his or her spouse within thirty days of the time of the conveyance if the conveyance involves an interest in real estate to which dower would have attached if the conveyance had been made before dower was abolished in 1992. 2. Under W.Va. Code § 43-1-2(d) [1992], when a married person fails to comply with the notice requirement contained in W.Va. Code § 43-1-2(b) [1992], then in the event of a subsequent divorce within five years of the conveyance, the value of the real estate conveyed, as determined at the time of the conveyance, shall be deemed a part of the conveyancer’s marital property for purposes of determining equitable distribution. i Justice Ketchum: Petitioner Ross Stanley (“petitioner husband”) appeals the July 30, 2013, order of the Circuit Court of Greenbrier County that reversed the April 19, 2013, order of the Family Court of Greenbrier County. -

Hidden Risks in Real Estate Title Transactions

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 14 1970 Hidden Risks in Real Estate Title Transactions Sherman Hollander Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Housing Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Sherman Hollander, Hidden Risks in Real Estate Title Transactions, 19 Clev. St. L. Rev. 111 (1970) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol19/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hidden Risks in Real Estate Title Transactions Sherman Hollander* N o AMOUNT OF CARE can avoid certain of the title hazards which a real estate transaction may encounter. The most careful attorney can do little or nothing, in such situations, to sidestep the pitfalls. In at least some such cases the legislature could provide relief by reducing the risk to innocent parties. To do so requires perceptive review of some time- honored concepts. A number of types of other problems exist where a careful attorney may reduce the risk faced by his client. Even here perhaps the legis- lature could consider statutory improvements. It would be more fair and equitable if extraordinary care were not required to prevent an un- just result. Dower Interest One vestige of English Common Law which still operates in Ohio and may be the source of increasing losses to innocent parties in the future is dower. -

Civil Union and Domestic Partmerships

Civil Union and Domestic Partmerships January 2014 In 2000, Vermont became the first state to recognize same-sex civil unions following the 1999 decision of Vermont’s Supreme Court in Baker v. Vermont, 744 A.2d 864 (Vt. 1999), holding that the state’s prohibition on same-sex marriage violated the Vermont Constitution. The court ordered the Vermont legislature either to allow same-sex marriages or to implement an alternative legal mechanism according similar rights to same-sex couples. As of November, 2013, these jurisdictions have laws providing for the issuance of marriage licenses to same-sex couples: California. Connecticut. Delaware. District of Columbia. Hawaii Illinois Iowa. Maine. Maryland. Massachusetts. Minnesota. New Hampshire. New Mexico New York. Rhode Island. Vermont. Washington. The following jurisdictions provide the equivalent of state-level spousal rights to same- sex couples within the state: Colorado. District of Columbia. Nevada. New Jersey. Oregon. Wisconsin. If a state does not appear on the following chart, it is because we have not found a state statute on the topic. In some cases provisions only exist for public employees. To check whether there is pending or recently enacted legislation, please click here. Click the letter corresponding to the state name below. Please note: This material is for personal use only and is protected by U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17 USC). It is provided as general information only and does not constitute and is not a substitute for legal or other professional advice. Reliance upon this material is solely at your own risk. | C | D | H | I | M | N | O | R | V | W State Statute California 297.