Child Custody Modification Under the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act: a Statute to End the Tug-Of-War?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expert Evidence in Favour of Shared Parenting 2 of 12 Shared Parenting: Expert Evidence

Expert evidence in favour of shared parenting 2 of 12 Shared Parenting: Expert Evidence Majority View of Psychiatrists, Paediatricians and Psychologists The majority view of the psychiatric and paediatric profession is that mothers and fathers are equals as parents, and that a close relationship with both parents is necessary to maximise the child's chances for a healthy and parents productive life. J. Atkinson, Criteria for Deciding Child Custody in the Trial and Appellate Courts, Family Law Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, American both Bar Association (Spring 1984). In a report that “summarizes and evaluates the major research concerning joint custody and its impact on children's welfare”, the American Psychological Association (APA) concluded that: “The research reviewed supports the conclusion that joint custody is parent is associated with certain favourable outcomes for children including father involvement, best interest of the child for adjustment outcomes, child support, reduced relitigation costs, and sometimes reduced parental conflict.” best The APA also noted that: the “The need for improved policy to reduce the present adversarial approach that has resulted in primarily sole maternal custody, limited father involvement and maladjustment of both children and parents is critical. Increased mediation, joint custody, and parent education are supported for this policy.” Report to the US Commission on Child and Family Welfare, American Psychological Association (June 14, 1995) The same American Psychological Association adopted -

Child Custody and Visitation Procedures

Kansas Legislator K a n s a s Briefing Book L e g i s l a t i v e R e s e a r c h 2015 D e p a r t m e n t D-1 Children and Youth Juvenile Services D-2 Child Custody and Visitation Procedures D-2 Child Custody In Kansas, “legal custody” is defined as “the allocation of parenting and Visitation responsibilities between parents, or any person acting as a parent, Procedures including decision making rights and responsibilities pertaining to matters of child health, education and welfare.” KSA 23-3211. Within that context, Kansas law distinguishes between “residency” and D-3 “parenting time.” Residency refers to the parent with whom the child Child in Need of lives, compared to parenting time, which consists of any time a parent Care Proceedings spends with a child. The term “visitation” is reserved for time nonparents are allowed to spend with a child. D-4 Adoption Initial Determination The standard for awarding custody, residency, parenting time, and visitation is what arrangement is in the “best interests” of the child. A trial judge can determine these issues when a petition is filed for: ● Divorce, annulment, or separate maintenance. KSA 23-2707 (temporary order); KSA 23-3206, KSA 23-3207, and KSA 23- 3208; ● Paternity. KSA 23-2215; ● Protection, pursuant to the Kansas Protection from Abuse Act (KPAA). KSA 60-3107(a)(4) (temporary order); ● Protection, in conjunction with a Child in Need of Care (CINC) proceeding. KSA 38-2243(a) (temporary order); KSA 38- 2253(a)(2)—for more information on CINC proceedings, see D-4; ● Guardianship of a minor. -

Chickasaw Nation Code Title 6, Chapter 2

Domestic Relations & Families (Amended as of 08/20/2021) CHICKASAW NATION CODE TITLE 6 "6. DOMESTIC RELATIONS AND FAMILIES" CHAPTER 1 MARRIAGE ARTICLE A DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE Section 6-101.1 Title. Section 6-101.2 Jurisdiction. Section 6-101.3 Areas of Jurisdiction. Section 6-101.4 Applicable Law. Section 6-101.5 Definitions of Marriage; Common Law Marriage. Section 6-101.6 Actions That May Be Brought; Remedies. Section 6-101.7 Consanguinity. Section 6-101.8 Persons Having Capacity to Marry. Section 6-101.9 Marriage Between Persons of Same Gender Not Recognized. Section 6-101.10 Grounds for Divorce. Section 6-101.11 Petition; Summons. Section 6-101.12 Notice of Pendency Contingent upon Service. Section 6-101.13 Special Notice for Actions Pending in Other Courts. Section 6-101.14 Pleadings. Section 6-101.15 Signing of Pleadings. Section 6-101.16 Defense and Objections; When and How Presented; by Pleadings or Motions; Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings. Section 6-101.17 Reserved. Section 6-101.18 Lost Pleadings. Section 6-101.19 Reserved. Section 6-101.20 Reserved. Section 6-101.21 Reserved. Section 6-101.22 Reserved. Section 6-101.23 Reserved. Page 6-1 Domestic Relations & Families Section 6-101.24 Reserved. Section 6-101.25 Reserved. Section 6-101.26 Reserved. Section 6-101.27 Summons, Time Limit for Service. Section 6-101.28 Service and Filing of Pleadings and Other Papers. Section 6-101.29 Computation and Enlargement of Time. Section 6-101.30 Legal Newspaper. Section 6-101.31 Answer May Allege Cause; New Matters Verified by Affidavit. -

Oklahoma Statutes Title 43. Marriage and Family

OKLAHOMA STATUTES TITLE 43. MARRIAGE AND FAMILY §43-1. Marriage defined. ............................................................................................................................... 8 §43-2. Consanguinity. .................................................................................................................................... 8 §43-3. Who may marry. ................................................................................................................................. 8 §43-3.1. Recognition of marriage between persons of same gender prohibited. ....................................... 10 §43-4. License required. ............................................................................................................................... 10 §43-5. Application - Fees - Issuance of license and certificate. ................................................................... 10 §43-5.1. Premarital counseling. ................................................................................................................... 11 §43-6. License - Contents. ............................................................................................................................ 12 §43-7. Solemnization of marriages. ............................................................................................................. 13 §43-7.1. Refusal to solemnize or recognize marriage by religious organization officials - Definitions. ....... 14 §43-8. Endorsement and return of license. ................................................................................................ -

Postadoption Contact Agreements Between Birth and Adoptive Families

STATE STATUTES Current Through August 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Postadoption Contact States with enforceable Agreements Between Birth contact agreements Who may be a party to and Adoptive Families an agreement? Postadoption contact agreements are The court’s role in arrangements that allow contact or establishing and enforcing agreements communication between a child, his or her adoptive family, and members of the child’s When do States use birth family or other persons with whom the mediation? child has an established relationship, such as a foster parent, after the child’s adoption has Laws in States without been finalized. These arrangements, sometimes enforceable agreements referred to as cooperative adoption or open Summaries of State laws adoption agreements, can range from informal, mutual understandings between the birth and adoptive families to written, formal contracts. To find statute information for a particular State, go to https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ laws-policies/state/. Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Postadoption Contact Agreements Between Birth and Adoptive Families https://www.childwelfare.gov Agreements for postadoption contact or communication for contact after the finalization of an adoption.2 The have become more prevalent in recent years due to written agreements specify the type and frequency of several factors: contact and are signed by the parties to an adoption prior to finalization.3 There is wider recognition of the rights of birth parents to make choices for their children. Contact can range from the adoptive and birth parents Many adopted children, especially older children, exchanging information about a child (e.g., cards, letters, such as stepchildren and children adopted from foster and photos via traditional or social media) to the child care, have attachments to one or more birth relatives exchanging information or having visits with the birth with whom ongoing contact may be desirable and parents or relatives. -

Family Systems Paradigm for Legal Decision Making Affecting Child Custody Susan L

Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 6 Article 1 Issue 1 Fall 1996 Family Systems Paradigm for Legal Decision Making Affecting Child Custody Susan L. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brooks, Susan L. (1996) "Family Systems Paradigm for Legal Decision Making Affecting Child Custody," Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FAMILY SYSTEMS PARADIGM FOR LEGAL DECISION MAKING AFFECTING CHILD CUSTODY Susan L. Brookst INTRODUCTION Sarah, a twelve-year-old child, was raped by the boyfriend of her mother, Ms. P.1 Ms. P. denied the rape. After an investigation, the state's department of human services filed a petition in juvenile court alleging that Sarah was dependent and neglected in that her mother failed to protect her from the perpetrator. The judge appointed a lawyer for Ms. P. and a separate Guardian Ad Litem ("GAL") lawyer to represent Sarah's "best interests." Despite Sarah's insistence that she wanted to remain with her mother, the judge ordered that Sarah be removed from Ms. P.'s home and placed in state custody. -

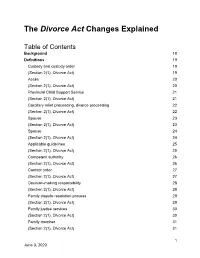

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Divorce, Annulment, and Child Custody

DIVORCE, ANNULMENT, AND CHILD CUSTODY : DISCLAIMER The information on this page is intended for educational purposes only. It is not legal advice. If you have specific questions, or are experiencing a situation where you need legal advice, you should contact an attorney. Student Legal Services makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information on this page. However, the law changes frequently and this site should not be used as a substitute for legal advice. It is highly recommended that anyone accessing this page consult with an attorney licensed in the state of Wyoming prior to taking any action based on the information provided on this page. DIVORCE A divorce is when two individuals petition the court to formally end their marriage. Divorce includes the division of marital property. If a couple has children, the court also will determine the custody arrangement for those children. You can learn more about divorce on the Equal Justice Wyoming website here. It is possible to complete the divorce process without an attorney. Completing the process without an attorney is called a “pro se divorce.” Divorces without attorneys are easiest when there are no children and the parties agree about the majority of the property distribution. You can access directions and packets for a pro se divorce here. ANNULMENT An annulment is when the marriage is dissolved as if it never existed. It is very hard to receive an annulment and most marriages will not qualify. Annulments occur in two situations. When the marriage is void and when the marriage is voidable. VOID MARRIAGES: When a marriage is void, it means that the marriage could not have taken place under the law—therefore it does not exist. -

Child-Focused Parenting Time Guide

Child-Focused Parenting Time Guide Prepared by the Minnesota State Court Administrator’s Advisory Committee on Child-Focused Parenting Time This Guide is located on the Minnesota Judicial Branch website. For further information, contact: Court Services Division State Court Administrator’s Office 105 Minnesota Judicial Center 25 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. St. Paul, MN 55155 651-297-7587 This Guide is not copyrighted and may be reproduced without prior permission of the Minnesota Judicial Branch, State Court Administrator’s Office. Child-Focused Parenting Time Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Legal Notice ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 5 Assumptions ................................................................................................................................ 5 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Audience .................................................................................................................................... -

Untying the Knot: an Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Common Law Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation Danaya C. Wright, Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866, 38 U. Rich. L. Rev. 903 (2004), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNTYING THE KNOT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENGLISH DIVORCE AND MATRIMONIAL CAUSES COURT RECORDS, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright * I. INTRODUCTION Historians of Anglo-American family law consider 1857 as a turning point in the development of modern family law and the first big step in the breakdown of coverture' and the recognition of women's legal rights.2 In 1857, The United Kingdom Parlia- * Associate Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law. This arti- cle is a continuation of my research into nineteenth-century English family law reform. My research at the Public Record Office was made possible by generous grants from the University of Florida, Levin College of Law. -

Effects of the 2010 Civil Code on Trends in Joint Physical Custody in Catalonia

EFFECTS OF THE 2010 CIVIL CODE ON TRENDS IN JOINT PHYSICAL CUSTODY IN CATALONIA. A COMPARISON WITH THE Document downloaded from www.cairn-int.info - Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 158.109.138.45 09/05/2017 14h03. © I.N.E.D REST OF SPAIN Montserrat Solsona, Jeroen Spijker I.N.E.D | « Population » 2016/2 Vol. 71 | pages 297 - 323 ISSN 0032-4663 ISBN 9782733210666 This document is a translation of: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Montserrat Solsona, Jeroen Spijker, « Influence du Code civil catalan (2010) sur les décisions de garde partagée. Comparaisons entre la Catalogne et le reste de Espagne », Population 2016/2 (Vol. 71), p. 297-323. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Available online at : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_POPU_1602_0313--effects-of-the-2010-civil-code- on.htm -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- How to cite this article : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Montserrat Solsona, Jeroen Spijker, « Influence du Code civil catalan (2010) sur les décisions de garde partagée. Comparaisons entre la Catalogne et le reste de Espagne », Population 2016/2 (Vol. 71), p. 297-323. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Custody and Child Symptomatology in High Conflict Divorce: an Analysis of Latent Profiles Characterized by Hostility, Escalating Distress, and Detachment

Psicothema 2021, Vol. 33, No. 1, 95-102 ISSN 0214 - 9915 CODEN PSOTEG Copyright © 2021 Psicothema doi: 10.7334/psicothema2020.224 www.psicothema.com Custody and Child Symptomatology in High Confl ict Divorce: An Analysis of Latent Profi les Ana Martínez-Pampliega1, Marta Herrero1, Susana Cormenzana1, Susana Corral1, Mireia Sanz2, Laura Merino1, Leire Iriarte1, Iñigo Ochoa de Alda3, Leire Alcañiz1, and Irati Alvarez2 1 University of Deusto, 2 Begoñako Andra Mari Teacher Training University College (BAM), and 3 University of the Basque Country Abstract Resumen Background: There is much controversy about the impact of joint physical Custodia y Sintomatología de los Hijos en Divorcios Altamente custody on child symptomatology in the context of high interparental Confl ictivos: Análisis de Perfi les Latentes. Antecedentes: existe una confl ict. In this study we analyzed child symptomatology with person- gran controversia acerca del impacto de la custodia física compartida centered methodology, identifying differential profi les, considering post- en la sintomatología infantil en contexto de alto confl icto interparental. divorce custody, parental symptomatology, and coparenting variables. We El presente estudio analizó la sintomatología infantil a través de una examined the association between these profi les and child symptomatology, metodología centrada en la persona, identifi cando perfi les diferenciales as well as the mediating role of parenting in that association. Method: al considerar las variables custodia postdivorcio, sintomatología parental The participants were 303 divorced or separated Spanish parents with y coparentalidad. Se analizó la asociación entre estos perfi les y la high interparental confl ict. We used the study of latent profi les and the sintomatología infantil, así como el papel mediador de la parentalidad.