The Constitution of Canada and the Conflict of Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Equity and the Innovative Tradition

CONSTITUTIONAL EQUITY AND THE INNOVATIVE TRADITION WILLIAM T. QUILLEN* I INTRODUCTION Lazard Freres & Company ("Lazard") and Dillon Read & Company, Inc. ("Dillon"), the investment bank advisers to the special committee of the board of directors of RJR Nabisco, Inc. ("RJR"), 1 moved to intervene in the recent Nabisco shareholder litigation in the Delaware Court of Chancery.2 The motion presented the court with the stuff of lawyers-personal jurisdiction, subject matter jurisdiction, mandatory counterclaims, mandatory and permissive intervention, declaratory judgments, collateral estoppel-in short, a feast for those of our craft who are determined that the elimination of common law pleading and antiquated bills in equity shall not spoil all the fun.3 The motion to intervene was presented to Chancellor William T. Allen, Chief Judge of the Delaware Court of Chancery. What is striking about the portion of the opinion dealing with subject matter jurisdiction is not its example of a now-rare breed of legal issues (that is, is the declaratory judgment counterclaim, being a strictly legal matter designed to negate liability for negligence, cognizable in a separate court of equity?), nor even the overall issues of the modern uniqueness of the Delaware bifurcated Copyright © 1993 by William T. Quillen * Delaware Secretary of State; Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law, Widener University School of Law, Wilmington, Delaware; former Chancellor, Delaware Court of Chancery; retired Justice, Delaware Supreme Court. This article is largely taken from a longer work. See William T. Quillen, A Historical Sketch of the Equity Jurisdiction in Delaware (1982) (unpublished LL.M. thesis, University of Virginia) [hereinafter Quillen, Historical Sketch]. -

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

Ntract Law Eform in Quebec

Vol . 60 September 1982 Septembre No . 3 NTRACT LAW EFORM IN QUEBEC P.P.C . HAANAPPEL* Montreal I. Introduction . Most of the law of contractual obligations in Quebec is contained in 1982 CanLIIDocs 22 the Civil Code of Lower Canada of 1966. 1 As is the case with the large majority of civil codes in the world, the Civil Code of Quebec was conceived, written and brought into force in a pre-industrialized environment. Its philosophy is one of individualism and economic liberalism . Much has changed in the socio-economic conditions of Quebec since 1866. The state now plays a far more active and im- portant role in socio-economic life than it did in the nineteenth century. More particularly in the field of contracts, the principle of equality of contracting parties or in.other words the principle of equal bargaining power has been severely undermined . Economic distribution chan- nels have become much longer than in 1866, which has had a pro- found influence especially on the contract of sale. Today products are rarely bought directly from their producer, but are purchased through one or more intermediaries so that there will then be no direct con- tractual link between producer (manufacturer) and user (consumer).' Furthermore, the Civil Code of 1866 is much more preoccupied with immoveables (land and buildings) than it .is with moveables (chat- tels) . Twentieth century commercial transactions, however, more often involve moveable than immoveable objects . * P.P.C. Haanappel, of the Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal. This article is a modified version of a paper presented by the author to ajoint session of the Commercial and Consumer Law, Contract Law and Comparative Law Sections of the 1981 Conference of the Canadian Association of Law Teachers. -

Compatibility of the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons with Canada’S Legal Framework and Its International Human Rights Obligations

ENDING STATELESSNESS STATELESSNESS ENDING Relating To e Status COMPATIBILITY Of Stateless Persons With Canada’s Legal OF THE Framework And Its International Human 1954 CONVENTION Rights Obligations A SPECIAL REPORT Ending STATELESSNESS W Y #IBELONG © United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2015 Researched And Written For UNHCR By Gregg Erauw ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ COMPATIBILITY OF THE 1954 CONVENTION RELATING TO THE STATUS OF STATELESS PERSONS WITH CANADA’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ITS INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN FOR UNHCR BY GREGG ERAUW © United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2015 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations or UNHCR. COMPATIBILITY OF THE 1954 CONVENTION RELATING TO THE STATUS OF STATELESS PERSONS WITH CANADA’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ITS INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Report .................................................................................................................... 3 The Purpose of the -

Manitoba, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Québec

Court File No. 38663 and 38781 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal) IN THE MATTER OF THE GREENHOUSE GAS POLLUTION ACT, Bill C-74, Part V AND IN THE MATTER OF A REFERENCE BY THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL TO THE COURT OF APPEAL UNDER THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS ACT, 2012, SS 2012, c C-29.01 BETWEEN: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN APPELLANT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUÉBEC INTERVENERS (Title of Proceeding continued on next page) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP Legal Services Branch, Constitutional Law Section Barristers & Solicitors 1230 - 405 Broadway Suite 2600, 160 Elgin Street Winnipeg MB R3C 3L6 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Michael Conner / Allison Kindle Pejovic D. Lynne Watt Tel: (204) 391-0767/(204) 945-2856 Tel: (613) 786-8695 Fax: (204) 945-0053 Fax: (613) 788-3509 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener Ottawa Agent for the Intervener -and - SASKATCHEWAN POWER CORPORATION AND SASKENERGY INCORPORATED, CANADIAN TAXPAYERS FEDERATION, UNITED CONSERVATIVE ASSOCIATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION OF SASKATCHEWAN INC., INTERNATIONAL EMISSIONS TRADING ASSOCIATION, CANADIAN PUBLIC HEALTH -

Practice and Procedure the Applicable Rules Of

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE THE APPLICABLE RULES OF EVIDENCE IN FEDERAL COURT: A SHORT PRIMER ON A TRICKY QUESTION Whether at trial or during interlocutory proceedings, litigators need to know the applicable rules of evidence, since there are import- ant variations in provincial evidence law. The largest difference, of course, is between the civil law of QueÂbec and laws of the nine common-law provinces. Yet significant differences exist even between the common law provinces themselves. Admissions made during discovery can be contradicted at trial in Ontario, but not in Saskatchewan.1 Spoliation of evidence requires intentional conduct in British Columbia before remedies will be granted, but not in New Brunswick.2 Evidence obtained through an invasion of privacy is inadmissible in Manitoba, while the other provinces have yet to legislate on this issue.3 1. Marchand (Litigation Guardian of) v. Public General Hospital Society of Chatham (2000), 43 C.P.C. (5th) 65, 51 O.R. (3d) 97, 138 O.A.C. 201 (Ont. C.A.) at paras. 72-86, leave to appeal refused [2001] 2 S.C.R. x, 156 O.A.C. 358 (note), 282 N.R. 397 (note) (S.C.C.); Branco v. American Home Assur- ance Co., 2013 SKQB 98, 6 C.C.E.L. (4th) 175, 20 C.C.L.I. (5th) 22 (Sask. Q.B.) at paras. 96-101, additional reasons 2013 SKQB 442, 13 C.C.E.L. (4th) 323, [2014] I.L.R. I-5534, varied on other issues without comment on this point 2015 SKCA 71, 24 C.C.E.L. -

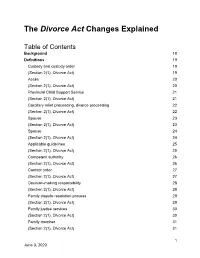

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

Untying the Knot: an Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Common Law Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation Danaya C. Wright, Untying the Knot: An Analysis of the English Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Court Records, 1858-1866, 38 U. Rich. L. Rev. 903 (2004), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNTYING THE KNOT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE ENGLISH DIVORCE AND MATRIMONIAL CAUSES COURT RECORDS, 1858-1866 Danaya C. Wright * I. INTRODUCTION Historians of Anglo-American family law consider 1857 as a turning point in the development of modern family law and the first big step in the breakdown of coverture' and the recognition of women's legal rights.2 In 1857, The United Kingdom Parlia- * Associate Professor of Law, University of Florida, Levin College of Law. This arti- cle is a continuation of my research into nineteenth-century English family law reform. My research at the Public Record Office was made possible by generous grants from the University of Florida, Levin College of Law. -

Language Planning and Education of Adult Immigrants in Canada

London Review of Education DOI:10.18546/LRE.14.2.10 Volume14,Number2,September2016 Language planning and education of adult immigrants in Canada: Contrasting the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia, and the cities of Montreal and Vancouver CatherineEllyson Bem & Co. CarolineAndrewandRichardClément* University of Ottawa Combiningpolicyanalysiswithlanguagepolicyandplanninganalysis,ourarticlecomparatively assessestwomodelsofadultimmigrants’languageeducationintwoverydifferentprovinces ofthesamefederalcountry.Inordertodoso,wefocusspecificallyontwoquestions:‘Whydo governmentsprovidelanguageeducationtoadults?’and‘Howisitprovidedintheconcrete settingoftwoofthebiggestcitiesinCanada?’Beyonddescribingthetwomodelsofadult immigrants’ language education in Quebec, British Columbia, and their respective largest cities,ourarticleponderswhetherandinwhatsensedemography,languagehistory,andthe commonfederalframeworkcanexplainthesimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwo.These contextualelementscanexplainwhycitiescontinuetohavesofewresponsibilitiesregarding thesettlement,integration,andlanguageeducationofnewcomers.Onlysuchunderstandingwill eventuallyallowforproperreformsintermsofcities’responsibilitiesregardingimmigration. Keywords: multilingualcities;multiculturalism;adulteducation;immigration;languagelaws Introduction Canada is a very large country with much variation between provinces and cities in many dimensions.Onesuchaspect,whichremainsacurrenthottopicfordemographicandhistorical reasons,islanguage;morespecifically,whyandhowlanguageplanningandpolicyareenacted -

Translating the Constitution Act, 1867

TRANSLATING THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1867 A Legal-Historical Perspective by HUGO YVON DENIS CHOQUETTE A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Law in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2009 Copyright © Hugo Yvon Denis Choquette, 2009 Abstract Twenty-seven years after the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Constitution of Canada is still not officially bilingual in its entirety. A new translation of the unilingual Eng- lish texts was presented to the federal government by the Minister of Justice nearly twenty years ago, in 1990. These new French versions are the fruits of the labour of the French Constitutional Drafting Committee, which had been entrusted by the Minister with the translation of the texts listed in the Schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 which are official in English only. These versions were never formally adopted. Among these new translations is that of the founding text of the Canadian federation, the Constitution Act, 1867. A look at this translation shows that the Committee chose to de- part from the textual tradition represented by the previous French versions of this text. In- deed, the Committee largely privileged the drafting of a text with a modern, clear, and con- cise style over faithfulness to the previous translations or even to the source text. This translation choice has important consequences. The text produced by the Commit- tee is open to two criticisms which a greater respect for the prior versions could have avoided. First, the new French text cannot claim the historical legitimacy of the English text, given their all-too-dissimilar origins. -

Paramountcy in Penal Legislation

OCCUPYING THE FIELD : PARAMOUNTCY IN PENAL LEGISLATION BORA LASKIN* Toronto Among the time-honoured doctrines of Canadian constitutional law none has a more disarming simplicity and none is more ques- tion-begging than the last of the four propositions proclaimed by Lord Tomlin in the Fish Canneries case' and repeated on three subsequent occasions by the Privy Council.2 It reads as follows : "There can be a domain in which Provincial and Dominion legisla- tion may overlap, in which case neither legislation will be ultra vires if the field is clear, but if the field is not clear and the two legislations meet the Dominion legislation must prevail."' The issues raised by this pronouncement are concomitants of federal- ism, familiar in the United States and in Australia, and immanent in the constitutions of the new federal states that have come into being since the end of World War Two.4 Three fairly recent decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, in each of which there were dissents, illustrate that court's ap- preciation ofthose issues as they emerged in provincial and federal penal legislation. The three cases are sufficiently different from one another in their facts and supporting legislation to provide adequate perspective for an examination of the doctrine of the "occupied field"-the paramountcy doctrine, to use an equivalent-as it pertains to penal enactments. *Bora Laskin, Q.C., of the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto. 1 A.-G. for Canada v. A.-G . for British Columbia, [1930] A.C. 111, [19301 1 D.L.R. 194, [192913 W.W.R. -

Product Liability Defense: Preemption in Canada

Product Liability Defence North and South of the Border: Is there such thing as Canadian pre-emption? By Craig Lockwood, Sonia Bjorkquist and Alexis Beale from Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP and Maura Kathleen Monaghan, Jacob W. Stahl and Christel Y. Tham from Debevoise & Plimpton LLP PRODUCT LIABILITY DEFENCE NORTH AND SOUTH OF THE BORDER Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp | Debevoise & Plimpton Table of Contents Introduction 3 An Overview of the U.S. Experience 5 The Canadian Experience 9 Recent Developments 15 Conclusion 19 2 PRODUCT LIABILITY DEFENCE NORTH AND SOUTH OF THE BORDER Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp | Debevoise & Plimpton 1 Introduction In Canada, most food products, pharmaceuticals, cosmetic products and medical devices are subject to federal regulation pursuant to the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) and other related legislation.1 Similar to the U.S. regulatory scheme, the Canadian regime is administered and enforced by the federal regulatory authorities – most notably Health Canada – responsible for establishing standards of safety for, and regulating and approving the use of, health-related products sold in Canada. However, U.S. manufacturers who sell regulated products in Canada may be surprised to learn that compliance with the FDA and associated regulatory frameworks has not historically served as a defence to product liability claims. In particular, the Canadian regulatory regime has traditionally operated as a ‘regulatory floor,’ rather than a comprehensive code of conduct. Conversely, applicable regulatory frameworks in the United States may prescribe comprehensive codes of conduct that do not leave the regulated entity with any discretion, potentially creating irreconcilable conflicts between the state and federal governments.