Migrant Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EQL Paper 20200315

EQL -- an extremely easy to learn knowledge graph query language, achieving high-speed and precise search Han Liu Shantao Liu Beijing Lemon Flower Technology Co., Ltd. 2020.3.15 Abstract: EQL , also named as Extremely Simple Query Language , can be widely used in the fields of knowledge graph, precise search, strong artificial intelligence, database, smart speaker, patent search and other fields. EQL adopts the principle of minimalism in design and pursues simplicity and easy to learn so that everyone can master it quickly. In the underlying implementation, through the use of technologies such as NLP and knowledge graph in artificial intelligence , as well as technologies in the field of big data and search engine, EQL ensure high- speed and precise information search, thereby helping users better tap into the wealth contained in data assets. EQL language and λ calculus are interconvertible, that reveals the mathematical nature of EQL language,and lays a solid foundation for rigor and logical integrity of EQL language. In essence, any declarative statement is equivalent to a spo fact statement. The mathematical abstract form of the spo fact statement is s: p: o (q1: v1, q2: v2 ..... qn: vn), s:p:o is subject:predicate:object, or entity : attribute : attribute value. (q1: v1, q2: v2 ..... qn: vn) are called modifiers to express more details, n is 0 or a natural number; any question statement is equivalent to one or more spo question statements, the basic form of each spo question statement is to replace any symbol of the spo fact statements with the ?x, for example, s: p:?x (q1: v1, q2: v2), or s: p: o (q1:?x, q2: v2, q3: v3). -

Download Moving House: Stories, Paweðłâ•I Huelle, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1995

Moving house: stories, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1995, 0151627312, 9780151627318, 248 pages. Stories deal with angels, devils, family disagreements, a hidden village, and a grandfather building his own submarine. DOWNLOAD HERE Moving house a novel, Katharine Moore, 1986, Business & Economics, 154 pages. You Can't Get Lost in Cape Town , ZoГ« Wicomb, 1987, Fiction, 214 pages. The South African novel of identity that "deserves a wide audience on a par with Nadine Gordimer.". The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories , Pagan Kennedy, 2008, Literary Collections, 247 pages. Presents a collection of literary writings that feature eccentrics and visionaries intent on transforming the world according to their peculiar ambitions.. House of day, house of night , Olga Tokarczuk, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Feb 12, 2003, Fiction, 293 pages. Richly imagined, weaving in anecdote with recipes and gossip, "House of Day, House of Night" is an epic of a small place. In Nowa Ruda, a small town in Silesia, Poland, the .... Pierwsza miЕ‚oЕ›Д‡ i inne opowiadania, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, 1996, , 251 pages. Pornografia/ Pornography , Witold Gombrowicz, 2009, Fiction, 225 pages. During the German occupation of Poland, two men who have abandoned Warsaw for the countryside occupy themselves by trying to force a tryst between two teenagers on a local farm .... The Darkest Clearing , Brian Railsback, Apr 1, 2004, Fiction, 327 pages. Equal parts intimate character study and page-turning thriller, this novel explores the extremes of both genres, combining a fascinating story with timely reflections on 21st .... Mercedes-Benz from Letters to Hrabal, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, 2005, History, 154 pages. -

POLISH CULTURE: LESSONS in POLISH LITERATURE (In English)

POLISH CULTURE: LESSONS IN POLISH LITERATURE (in English) July 6-24, 12:30-14:00 Polish time; 30 academic hours, 2 credits/ECTS points Lecturer: Karina Jarzyńska Ph.D., karina.jarzyń[email protected] The course will be held on Microsoft Teams. All participants who marked this course on their application form will receive an invitation from the professor. Requirements for credits/ECTS points: Credits/ECTS points will be given to students who 1) attend the classes (missing no more than 1 lecture; each additional absence -5%) – 40%; 2) pass the final online exam on the last day of the course – 60%: a multiple-choice test with a few open-ended questions, 60 min. All the required material will be covered during the lectures. 3) Grading scale: 94–100% A excellent/bardzo dobry 87–93,9 B+ very good/+dobry 78–86,9 B good/dobry 69–77,9 C+ satisfactory/+dostateczny 60–68,9 C sufficient/dostateczny 0–59,9 F fail/niedostateczny Please keep in mind that if you don’t take the exam the course will not be listed on your Transcript of Studies (as if you had never taken it). SCHEDULE July 6, Monday HOW TO RECOGNIZE A PIECE OF POLISH LITERATURE, WHEN YOU SEE ONE? ON THE TIME, SPACE AND LANGUAGE(S) July 7, Tuesday “THE POLES ARE NOT GEESE, HAVE A TONGUE OF THEIR OWN”. THE FOUNDATION OF A LITERARY TRADITION July 8, Wednesday SARMATISM AND ITS AFTERLIFE July 9, Tursday ROMANTIC NATIONALISM À LA POLONAISE. ON THREE MESSIANIC PLAYS AND ONE NATIONAL EPIC July 10, Friday BETWEEN ROMANTICISM AND REALISM July 13, Monday HOW TO BECOME A SOCIETY OR “THE WEDDING” BY WYSPIAŃSKI -

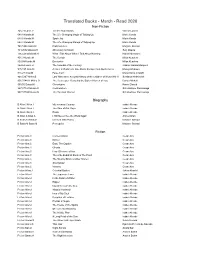

Read 2020 Book Lists

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

Poland Through Film EUS 3930 Section 0998 PLT 3930 Section 15EH EUH3931 Section 2H89 Dr

Poland Through Film EUS 3930 Section 0998 PLT 3930 Section 15EH EUH3931 Section 2H89 Dr. Jack J. B. Hutchens Turlington Hall 2341 Tuesdays: 3-4:55 Thursdays: 4:05-4:55 Poland Through Movies is an introductory survey of more than one thousand years of Polish history, illustrated on film. Poland’s contribution to world cinema has been immense. This class offers an examination of the chief currents of modern Polish film, including, but not limited to, the cinema of “the Polish School” of the 1950s and 60s, the works of experimental and avant- garde auteurs, satires and parodies of the late-socialist period, historical “great canvas” films, as well as more recent work that addresses the dramas, desires, and discontents of political transition and the realities of post-communist society. We will discuss the ways Polish filmmakers have represented Polish history, and how they have “read” history through their work. We will consider Polish cinema within the context of both Western European film and film production in the Soviet Bloc. A main focus will be on the oeuvre of Poland’s most recognized and prodigious filmmakers, including Wajda, Kieslowski, Ford, Polanski, Holland, Zanussi, and Hoffman, as well as on the work of “Wajda’s children” – the newest generation of filmmakers. Class time will consist of lecture & discussion, viewings, and class presentations. Required Texts: -Haltof, Marek. Polish National Cinema (paperback). ISBN-10: 1571812768; ISBN-13: 978-1571812766 -Zamoyski, Adam. Poland: A History. ISBN-13: 978-0007282753. -Zmoyski, Adam. Holy Madness: Romantics, Patriots and Revolutionaries, 1776-1871. ISBN-10: 0141002239 Recommended Texts: -Coates, Paul. -

Maria Dernałowicz "Obraz Literatury Polskiej XIX I XX Wieku

Maria Dernałowicz "Obraz literatury polskiej XIX i XX wieku. Vol. 1-4", red. Kazimierz Wyka, Henryk Markiewicz, Irena Wyczańska, Kraków 1975 : [recenzja] Literary Studies in Poland 5, 189-191 1980 The Informations Les Informations Obraz Literatury Polskiej XIX i XX wieku (The Picture of Polish Literature of the 19th and 20th Century), Series III: Literatura kra jowa w okresie romantyzmu 1831 — 1863 (Literature in Poland in the Romantic Period 1831 — 1863), vol. 1: Kraków 1975, vol. 2 —in print, vol. 3 and 4 —in preparation. The development of Polish Romanticism, the trend which had become victorious in Poland before 1830 with such outstanding works as Antoni Malczewski's Maria, Seweryn Goszczyńskie Zamek kaniow ski (The Castle of Kaniów) and, above all, with Adam Mickiewicz's poetry, from Ballads and Romances to Konrad Wallenrod, after 1831, after the collapse of the November uprising, took two different cour ses: in emigration, where the greatest poets of the epoch, like Mic kiewicz and Słowacki, lived, and in the partitioned Poland. Series III of The Picture o f Polish Literature is devoted to that Roman ticism which developed in Poland and which, though presently less known than the literature written in the Great Emigration, exerted considerable influence on the spiritual formation of Poles. Included in the Series are both syntheses and portraits of particular writers (analysis of their works, bibliography, anthology of texts), prepared by the best scholars in the field of history of Romanticism. In the main, writers presented in this Series are, with such rare exceptions as Aleksander Fredro, minor artists, to a great extent influenced by the conventions of the pre-November Romanticism. -

Polish Literature from 1918 to 2000: an Anthology Andrea Lanoux Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Slavic Studies Faculty Publications Slavic Studies Department Spring 2010 (Review) Polish Literature from 1918 to 2000: An Anthology Andrea Lanoux Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/slavicfacpub Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Lanoux, Andrea. "Polish Literature From 1918 To 2000: An Anthology. Bloomington." Slavic & East European Journal 54.1 (2010): 194-5. Web. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Slavic Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Slavic Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. 194 Slavic and East European Journal Michael J. Mikoý, ed. and trans. Polish Literatureftom 1918 to 2000: An Anthology. Blooming- toil, IN: Slavica Publishers, 2008. Select bibliography. Illustrations. xiv + 490 pp. $44.95 (cloth). This is the crowning achievement in a series of six anthologies of Polish literature selected and translated by Michael Mikoý, and spanning the medieval period to the recent past. The present volume covers Polish literature from 1918 to the year 2000, and serves as a comprehensive compendium of the broad spectrum of literature produced throughout the century. The book is divided into the interwar (1918-1939) and postwar (1945-2000) periods, with each part con- taining its own historical introduction and select bibliography. The introductions to both parts sketch the political and cultural contexts, listing the major historical events, figures, and works of that period, while the bibliographies following the two parts point the reader to topics for fu- ture study. -

Health As an Investment in Poland in the Context of the Roadmap to Implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Health 2020

Health as an investment in Poland in the context of the Roadmap to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Health 2020 Katarzyna Dubas-Jakóbczyk, Ewa Kocot, Aleksandra Czerw, Grzegorz Juszczyk, Paulina Karwowska, Bettina Menne Abstract The aim of this report is to assess the policy options for investments in health in Poland in the context of the Roadmap to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, building on Health 2020, the European Policy for Health and Well-being. As background, national strategic documents incorporating the concept of health and well-being for all were reviewed and methodological aspects of the health-as-investment approach presented. Methods included a literature review and desk analysis of key national regulations as well as quantitative analysis of indicators used to monitor the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Health 2020 policy implementation. The results indicate that the policy options for investment in health in Poland can be divided into two categories: general guidelines on building and promoting the investment approach and more specific examples of actions on health investments supporting the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Health 2020 strategies. KEYWORDS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT HEALTH POLICY INVESTMENT APPROACH RETURN ON INVESTMENT Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe UN City, Marmorvej 51 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office website (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). Citation advice Dubas-Jakóbczyk K, Kocot E, Czerw A, Juszczyk G, Karwowska P, Menne B. -

POLES and JEWS TODAY Madeline G. Levine "Everyone Knows That Poles Imbibe Anti~Semitism with Their M

WRESTLING WITH GHOSTS: POLES AND JEWS TODAY Madeline G. Levine "Everyone knows that Poles imbibe anti~Semitism with their mothers' milk." '1t's a well-known fact that those who accuse Poles of anti-Semitism are enemies of Poland." Everyone who has spent any time talking to Poles and Jews about the relations between them has heard some version of the sentiments paraphrased in these two comments. Even though Jews and Poles no longer live together in Poland, the simple phrase "Poles and Jews" evokes powerful emotions. Jews have bitter memories of friction and conflict, of being despised and threatened by Poles. Distrust of and dislike of Poles is handed down within the culture; most Jews today have had no personal experience of living among Poles. In contrast, when challenged to think about Polish-Jewish relations, Poles are quite likely to recall the good old days before the Nazis came when Poles and Jews got along very well with each other. But this sentimental memory is often linked with a sense of betrayal; since Jewish-Polish relations are remembered as good, Jewish accusations of Polish anti-Semitism are perceived as base ingratitude, if not treachery. In the ethnic cauldron that is Eastern Europe, there is nothing unusual about the historic frictions between Poles and Jews, for there can be little doubt that intense ethnic animosity is one of the principal features of the region. To be sure, Eastern Europe is not unique in this regard Ethnic conflict is a universal phenomenon, emerging from a tangled web of linguistic, religious, economic, and (broadly defined) cultural differences. -

GIPE-011178-Contents.Pdf (1.212Mb)

-Poland T.HE .MODERN WORLD A SURVEY OF HISTORICAL FORCES Edited by Rt. Hon. H. A. L. Fisher, f.R.S. ~ The aim of the volumes in this series is to provide a balanced survey, With such historical illustrations as are necessary, of the tendencies and forces, political, economic, intellectual, which are moulding tpe lives of COD:.temporary states. Alrea~y Published t ARABIA by .H. St. J. Philby AUSTRALIA by Professor W. K. Hancock CANADA by Professor Alexander ;Br~dy EGYPT by George Young ENGLAND by Dean lnge FRANCE by Sisley Huddleston G:J;:RMANY by G. P. Gooch .GREECE by W. Miller · · . I"NDIA by.Sit .Valentine Chirol. · IRELAND by Stephen Gwynn · ITALY by Luigi Villari JAPAN by I. Nitobe NORWAY by Gathorne Hardy PERSIA by Sir Arnold T. Wilson POLAND by Professor Roman Dyboski ·RUSSIA by N. Makeev and V. O'Hara SOUTH AFRICA by Jan H. ~Hofmeyr ·~ SPAIN by S. de Madariaga . TURKEY by Arnold Toynbee and. K. P. Kirkwood In Preparation : HUNGARY by C. A. Macartney 'JUGO-SLAVIA by Dr. R. W. Seton-Watson NEW ZEALAND by Dr. \V. P. Morrell scoTLAND by-Dr. R. S. Rait and G. Pryde u.s.A. by S. K. Ratcliffe POLAND- . By ROMAN DYBOSKI ' Ph.D., Professor of English Literature in lhe University of Cracow With t1 Forewortl by H. A. L •. -FISHER P.C., D.C.L. London Ernest Benn Limited I 9 3 3 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN POLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FoREWORD 9 AUTHORS PREFACE. ,,.. II •. I. THE OLD PoLAND .. IS 1. The unique fate of Poland.-z. -

1 Independence Regained

1 INDEPENDENCE REGAINED The history of Poland in the modern era has been characterised by salient vicissitudes: outstanding victories and tragic defeats, soaring optimism and the deepest despair, heroic sacrifice and craven subser- vience. Underpinning all of these experiences and emotions, however, are the interrelated themes of national freedom, independence and sovereignty, which were sometimes lost, then regained, but never forgotten or abandoned. They, more than anything else, shaped Poland’s destiny in the modern era. And if there is one single, fundamental point of reference, then it is unquestionably the Partitions of the eighteenth century which resulted in Poland’s disappearance from the map of Europe for well over a century. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, as the Polish State was consti- tuted since the mid-sixteenth century, was for the next two hundred years one of the largest and most powerful in Europe, occupying a huge swathe of territory stretching from the area around Poznań in the west to far-off Muscovy in the east, and from Livonia in the north to the edge of the Ottoman Empire in the south. Famous kings, such as Stefan Batory (1575–86) and Jan Sobieski III (1674–96), and great landowning families, the Lubomirskis, Radziwiłłs, Zamoyskis, Czartoryskis and the like, played a leading role in moulding the economic, political and social life of the country and bringing it unprecedented international prestige. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, the first unmistakable signs of decline appeared, and were accentuated by the emergence of ambitious and expansionist neighbours in Russia, Prussia and Austria. -

Udal Liburutegi Nagusia - Biblioteca Municipal Central

Udal Liburutegi Nagusia - Biblioteca Municipal Central Euskaraz. Iñigo Aranbarri (dinamatzailea) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 19:30 1 2 5 3 0 n I Irailak 17 Septiembre Deklaratzekorik ez / Beñat Sarasola Urriak 8 Octubre Hezurren erretura / Miren Agur Meabe Azaroak 5 Noviembre Esnearen kolorekoa / Nall Leyshon Abenduak 3 Diciembre Basa / Miren Amuriza Urtarrilak 14 Enero Babilonia / Joan Mari Irigoien Otsailak 11 Febrero Trikua esnatu da : euskaratik feminismora eta feminismotik euskarara / Lorea Agirre Dorronsoro Martxoak 10 Marzo Aldibereko / Ingeborg Bachmann Apirilak 7 Abril Urtaroak eta zeinuak / Jon Gerediaga Maiatzak 12 Mayo Miñan / Amets Arzallus www.donostiakultura.eus/liburutegiak @DK_Liburutegiak [email protected] En castellano. Amaia García (dinamizadora) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 19:30 Irailak 17 Septiembre El quinto hijo / Doris Lessing Urriak 22 Octubre Gloria / Vladimir Nabokov Azaroak 26 Noviembre Yo voy, tú vas, él va / Jenny Erpenbeck Abenduak 17 Diciembre Ordesa / Manuel Vilas (escritor invitado) Urtarrilak 28 Enero El rumor del oleaje / Yukio Mishima Otsailak 25 Febrero Persuasión / Jane Austen Martxoak 31 Marzo La campana de cristal / Sylvia Plath Apirilak 28 Abril Mañana tendremos otros nombres / Patricio Pron (escritor invitado) 1 2 Maiatzak 26 Mayo El desierto de los tártaros / Dino Buzzati 5 3 0 n I Ekainak 30 Junio Mejor hoy que mañana / Nadine Gordimer www.donostiakultura.eus/liburutegiak @DK_Liburutegiak [email protected] In english. Slawka Grabowska (coordinator) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 18:45 Irailak 16 Septiembre The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie / Muriel Spark Urriak 14 Octubre In a Free State / V.S. Naipaul Azaroak 11 Noviembre Lolly Willowes / Sylvia Townsend Warner Abenduak 9 Diciembre Pygmalion / George Bernard Shaw Urtarrilak 14 Enero The Man in the High Castle / Philip K.