Special Issue: Research from the USF Master of Arts in Asia Pacific Studies Program Editor's Introduction Protectionist Capita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DJ Honda HII Mp3, Flac, Wma

DJ Honda HII mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: HII Country: US Released: 1998 MP3 version RAR size: 1376 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1944 mb WMA version RAR size: 1986 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 863 Other Formats: RA AA AIFF MP1 VQF TTA ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Roc Raida Intro 1 1:10 Producer – Roc RaidaScratches – Roc Raida Trouble In The Water 2 3:45 Featuring – De La Soul 5 Seconds 3 3:58 Featuring – Black Attack Hai! 4 3:25 Featuring – 50 Grand, Keith Murray Every Now & Then 5 2:21 Featuring – Syndicate* Mista Sinista Interlude 6 1:04 Producer – Mista SinistaScratches – Mista Sinista Team Players 7 4:42 Featuring – KRS-One, Doe-V* On The Mic 8 3:45 Featuring – A.L., Cuban Link, Juju , Missin' LinxProducer – Vic* For Every Day That Goes By 9 3:31 Featuring – Rawcotiks WKCR Interlude 10 0:51 Featuring – Lord Sear, Stretch Armstrong Who The Trifest? 11 3:37 Featuring – The Beatnuts Talk About It 12 3:12 Featuring – Al' Tariq Blaze It Up 13 4:09 Featuring – Black Attack 14 DJ Ev Interlude 0:30 Go Crazy 15 2:52 Featuring – S-On Around The Clock 16 3:37 Featuring – Problemz When You Hot You Hot 17 4:12 Featuring – Dug Infinite, No I.D. Interlude 18 1:04 Featuring – Fat Lip Travellin´ Man 19 5:16 Featuring – Mos Def Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Relativity Copyright (c) – Relativity Manufactured By – Sony Music Entertainment (Canada) Inc. Distributed By – Sony Music Entertainment (Canada) Inc. Mastered At – Sterling Sound Credits Mastered By – Tom Coyne Producer – DJ Honda (tracks: 2 to 5, 7 to 19) -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

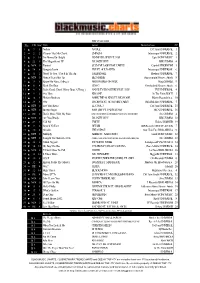

8 Nothin` NORE Def Jam/UNIVERSAL 1 2 Cleanin

KW 39/40/2002 Plz LW WoC Title Artist Distribution PP 1 ▲ 9 8 Nothin` N.O.R.E. Def Jam/UNIVERSAL 1 2 ➔ 2 2 Cleanin´Out My Closet EMINEM Interscope/UNIVERSAL 2 3 ▲ 5 10 I’m Gonna Be Alright JENNIFER LOPEZ FT. NAS Epic/SONY MUSIC 1 4 ▲ 22 8 The Magnificent EP DJ JAZZY JEFF BBE/ZOMBA 4 5 ▲ NEW 0 Tainted SLUM VILLAGE FEAT. DWELE Capitol/VIRGIN/EMI 5 6 ▲ 24 6 Gangsta Lovin EVE FT. ALICIA KEYS Interscope/UNIVERSAL 6 7 ▲ 11 2 Good To You / Put It In The Air TALIB KWELI Rawkus/UNIVERSAL 7 8 ▲ NEW 0 Games/Tear Shit Up BIZ MARKIE Superrappin/Groove Attack 8 9 ▲ 19 6 Know My Name (Mixes) NIGHTMARES ON WAX Warp/ZOMBA 9 10 ▼ 6 4 Rock The Beat EDO G Overlooked/Groove Attack 6 11 ▼ 4 8 Feels Good (Don’t Worry Bout A Thing ) NAUGHTY BY NATURE FEAT. 3LW TVT/UNIVERSAL 4 12 ▼ 3 2 Ova Here KRS ONE In The Paint/KOCH 3 13 ▲ 16 4 Harlem Brothers MARK THE 45 KING FT. BIG POOH Blazin Records/n.a. 10 14 ▲ 39 6 War DJ DESUE FT. AG & PARTY ARTY Rah Rah Ent./UNIVERSAL 5 15 ▲ NEW 0 Luv You Better LL COOL J Def Jam/UNIVERSAL 15 16 ▲ NEW 0 Brown Sugar MOS DEF FT. FAITH EVANS MCA/UNIVERSAL 16 17 ➔ RE 6 Don´t Mess With My Man NIVEA FEAT BRIAN & BRANDON CASEY OF JAGGED EDGE Jive/ZOMBA 4 18 ▲ NEW 0 Are You Ready DJ JAZZY JEFF BBE/ZOMBA 18 19 ▲ 27 8 Call Me TWEET Elektra/WARNER 19 20 ▼ 7 6 Smack Ya Face DEFARI ABB Records/GROOVE ATTACK 7 21 ▲ 30 4 Grindin THE CLIPSE Star Trak Ent./BMG ARIOLA 21 22 ▲ NEW 0 Multiply XZIBIT FT. -

The Future Is History: Hip-Hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity

The Future is History: Hip-hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College From The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by Ian Peddie (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2006). When hip-hop first broke in on the (academic) scene, it was widely hailed as a boldly irreverent embodiment of the postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, a cut-up method which would slice and dice all those old humanistic truisms which, for some reason, seemed to be gathering strength again as the end of the millennium approached. Today, over a decade after the first academic treatments of hip-hop, both the intellectual sheen of postmodernism and the counter-cultural patina of hip-hip seem a bit tarnished, their glimmerings of resistance swallowed whole by the same ubiquitous culture industry which took the rebellion out of rock 'n' roll and locked it away in an I.M. Pei pyramid. There are hazards in being a young art form, always striving for recognition even while rejecting it Ice Cube's famous phrase ‘Fuck the Grammys’ comes to mind but there are still deeper perils in becoming the single most popular form of music in the world, with a media profile that would make even Rupert Murdoch jealous. In an era when pioneers such as KRS-One, Ice-T, and Chuck D are well over forty and hip-hop ditties about thongs and bling bling dominate the malls and airwaves, it's noticeably harder to locate any points of friction between the microphone commandos and the bourgeois masses they once seemed to terrorize with sonic booms pumping out of speaker-loaded jeeps. -

The Politics of Independent Hip-Hop a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Just Say No to 360s: The Politics of Independent Hip-Hop A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Christopher Sangalang Vito June 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Ellen Reese, Chairperson Dr. Adalberto Aguirre, Jr. Dr. Lan Duong Dr. Alfredo M. Mirandé Copyright by Christopher Sangalang Vito 2017 The Dissertation of Christopher Sangalang Vito is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my family and friends for their endless love and support, my dissertation committee for their care and guidance, my colleagues for the smiles and laughs, my students for their passion, everyone who has helped me along my path, and most importantly I would like to thank hip-hop for saving my life. iv DEDICATION For my mom. v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Just Say No to 360s: The Politics of Independent Hip-Hop by Christopher Sangalang Vito Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Sociology University of California, Riverside, June 2017 Dr. Ellen Reese, Chairperson My dissertation addresses to what extent and how independent hip-hop challenges or reproduces U.S. mainstream hip-hop culture and U.S. culture more generally. I contend that independent hip-hop remains a complex contemporary subculture. My research design utilizes a mixed methods approach. First, I analyze the lyrics of independent hip-hop albums through a content analysis of twenty-five independent albums from 2000-2013. I uncover the dominant ideologies of independent hip-hop artists regarding race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and calls for social change. -

Download Issue

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 2 15 September · 2006 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez Special Issue: Research from the USF Master of Arts in Asia Pacific Studies Program John Nelson Editorial Consultants Editor’s Introduction Barbara K. Bundy >>.....................................................................John Nelson 1 Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Richard J. Kozicki Protectionist Capitalists vs. Capitalist Communists: CNOOC’s Failed Unocal Bid In Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Perspective Xiaoxin Wu >>.......................................................... Francis Schortgen 2 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka Bih-hsya Hsieh Economic Reform in Vietnam: Challenges, Successes, and Suggestions for the Future Uldis Kruze >>.....................................................................Susan Parini 11 Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Noriko Nagata United Korea and the Future of Inter-Korean Politics: a Work Already in Progress Stephen Roddy >>.......................................................Brad D. Washington 20 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick A Hard or Soft Landing for Chinese Society? Social Change and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games >>.....................................................Charles S. Costello III 25 Dashing Out and Rushing Back: The Role of Chinese Students Overseas in Fostering Social Change in China >>...........................................................Dannie LI Yanhua 34 Hip Hop and Identity Politics in Japanese Popular Culture >>.......................................................Cary -

MTO 7.4: Walker, Review of Krims

Volume 7, Number 4, July 2001 Copyright © 2001 Society for Music Theory Jonathan Walker KEYWORDS: hip-hop, cultural studies, pop music, African-American music, textural analysis, Ice Cube [1] By the end of the 1960s, the coalition of forces involved in civil rights campaigning had dissolved: white liberals who were happy to call for voting rights and an end to de jure segregation blanched when Malcolm X and eventually Martin Luther King condemned government and business interests in northern cities for their maintenance of economic inequality and de facto segregation; SNCC and CORE expelled their white members and came under increasing police surveillance and provocation; the Black Panthers seized the moment by putting into practice the kind of self defense Malcolm X had called for, but even they collapsed under sustained and violent FBI suppression. At the same time Nixon encouraged the suppression of radical black movements, he finessed the Black Power movement, turning it into a mechanism for generating black entrepreneurs and professionals to be co-opted by the system under the cloak of radical rhetoric.(1) [2] Black musical culture may have become big business in the 60s, but it was still responsive to changes in the black community. The non-violence of the early-60s campaigns had been dependent on its appeal to the conscience of the Washington political establishment, or on its threat to their international image (it certainly wasn’t going to pull on the heartstrings of the southern police and Citizens’ Councils); when this strategy -

Xavier University Newswire

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 1996-09-11 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (1996). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 2748. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/2748 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Students clubbed on mall . photo by RC DeJesus Members of the Black F~aternities and Sororities display their pride. (above) Students gathered on the Residental Mall to learn ab!Jut clubs and receive free food. (right) BvJoE~RISA activities. Clubs pertaining to specific THE XAVIER NEWSWIRE majors, from Theology and '.\ · ·,, On Monday. Sept. 9, the · Philosophy to Biology a.nd • .,_ ~-· t,:1~~~-·......... -1' ........ ,..,.+.~,,_..... 1.J ... ~-·-'-· .... ·~···- Residential Mall was trans- · PfiysiCs ·~ere 're'pres~·nte(c · . .. ..... ~ formed from strips of brick, ·· -' Then~ were many· athletic grass and trees into a carnival of Clubs offering information. color, music, people and most Even Xavier's Boxing Club, importantly, clubs eagerly which hosted a regional tourna · awaiting new members. ment last year, was attracting . Club Day on the Mall more members to the ring.- . 1996 included over 80 clubs · Xavier Crew, which i.s the which vied for the time, energy largest of the recreational clubs, as and participation of Xavier's well as the oldest sporting club on student population. -

“Respect for Da Chopstick Hip Hop” Th E Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy of Cantonese Verbal Art in Hong Kong

TRACK 8 “Respect for Da Chopstick Hip Hop” Th e Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy of Cantonese Verbal Art in Hong Kong Angel Lin My message is to ask people to refl ect, to use their brains to think and their hearts to feel—MC Yan. Introduction: Th e Arrival of Hip Hop onto the Music Scene in Hong Kong Th e music scene in Hong Kong has been dominated by Cantopop (Cantonese pop songs) since the mid-1970s. Th e early prominent Cantopop lyricists and singers such as Sam Hui were legendary in laying the foundation of the genre and the tradition of the lyrical styles which appeal to the masses through the rise of local Cantonese cinema and television. With easy-listening melody and simple lyrics about ordinary working-class people’s plight, Sam Hui’ s music and lyrical style marked the genesis of a new popular music form in Hong Kong, known as Cantopop (Erni, 2007). Cantopop has arisen as an indigenous music genre that the majority of Hong Kong people identity with. It has served as “a strategic cultural form to delineate a local identity, vis-à-vis the old British colonial and mainland Chinese identities” (McIntyre, Cheng, & Zhang, 2002, p. 217). However, Cantopop since the 1990s has become increasingly monopolized by a few mega music companies in Hong Kong that focus on idol-making, mainly churning out songs about love aff airs, and losing the early versatility that had existed in the themes of Cantopop lyrics (e.g., about working-class life, about friendship and family relationships, about life philosophy, etc.) (Chu, 2007). -

Independent Hip Hop Artists in Hong Kong: Youth Sub-Cultural Resistance and Alternative Modes of Cultural Production

Independent Hip Hop Artists in Hong Kong: Youth Sub-cultural Resistance and Alternative Modes of Cultural Production Angel Lin, Associate Professor Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Citation: Lin, A. M. Y. (2007). Independent hip hop artists in Hong Kong: Youth sub-cultural resistance and alternative modes of cultural production. Journal of Communication Arts , 25 (4), 47-62. Abstract In this paper I draw on ethnographic observations, interactions and in-depth interviews with key artists in the independent (indie) hip hop music scenes in Hong Kong to research the biographic stories and independent artistic practices situated in their socioeconomic and youth sub-cultural contexts. Then I analyse these ethnographic findings in relation to Bourdieu’s (1993) theoretical framework of “fields of cultural production” and discuss how these youth sub-cultural energies have found for themselves a niche space within the field of cultural production to resist the relentless capitalist practices of the pop culture/music industry. Introduction My research on the independent hip hop music scene in Hong Kong is carried out by way of biography study of key hip hop artists, specifically, through the case study of a key independent hip hop artist and his associates in Hong Kong. I shall discuss the conditions under which modes of creative cultural production alternative to capitalist modes can be made possible, and how these independent artists tactically find ways to craft out their niche space for survival and for innovative cultural production, sometimes by capitalizing on new media technologies (e.g., the Internet). -

Lorentz, Korinna

MASTERARBEIT im Studiengang Crossmedia Publishing & Management Erfolgversprechende Melodien – Analyse der Hooklines erfolgreicher Popsongs zur Erkennung von Mustern hinsichtlich der Aufeinanderfolge von Tönen und Tonlängen Vorgelegt von Korinna Gabriele Lorentz an der Hochschule der Medien Stuttgart am 08. Mai 2021 zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines „Master of Arts“ Erster Betreuer und Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Wiesener Zweiter Betreuer und Gutachter: Prof. Oliver Curdt E-Mail: [email protected] Matrikelnummer: 39708 Fachsemester: 4 Geburtsdatum, -ort: 15.04.1995 in Kiel Danksagung Mein größter Dank gilt Professor Dr. Oliver Wiesener für das Überlassen des Themas und die umfangreiche Unterstützung bei methodischen und stochastischen Überlegungen. Ich danke ihm insbesondere dafür, dass er trotz einiger anderer Betreuungsprojekte meine Masterarbeit angenommen hat und somit meinen Wunsch, im Musikbereich zu forschen, ermöglicht hat. Des Weiteren möchte ich meinem Freund und meiner Familie dafür danken, dass sie sich meine Problemstellungen bis zum Ende hin angehört haben und mir immer wieder Inspi- rationen für neue Lösungswege geben konnten. Besonderer Dank gilt meiner Mutter, Gabriele Lorentz, mit der ich interessante Gespräche zu musikalischen Themen führen konnte und mei- nem Vater, Dr. Thomas Lorentz, mit dem ich nächtliche Diskussionen über Markov-Ketten und Neuronale Netzwerke hatte. Ich danke meinen Eltern und meinem Freund, Michael Feuerlein, für die kritische Durchsicht der Arbeit. Kurzfassung In der vorliegenden Masterarbeit wurden die Melodie-Hooklines von Popsongs, die in Deutsch- land zwischen 1978 und 2019 sehr erfolgreich waren, explorativ analysiert. Ziel war, zu unter- suchen, ob gewisse Muster in den Reihenfolgen der Töne und Tonlängen vorkommen, und diese zu finden. Für die Mustersuche wurden Markov-Ketten erster, zweiter und dritter Ord- nung sowie Chi-Quadrat-Anpassungstests berechnet. -

The Values of Independent Hip-Hop in the Post-Golden Era Hip-Hop’S Rebels

The Values of Independent Hip-Hop in the Post-Golden Era Hip-Hop’s Rebels Christopher Vito The Values of Independent Hip-Hop in the Post-Golden Era Christopher Vito The Values of Independent Hip-Hop in the Post-Golden Era Hip-Hop’s Rebels Christopher Vito Southwestern College Chula Vista, CA, USA ISBN 978-3-030-02480-2 ISBN 978-3-030-02481-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02481-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958592 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.