The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Americanlegionwe236amer.Pdf (3.681Mb)

L Phil ANt'NT F I ^AMERICAN LEGION m Ao. 36 OCTOBER 1, i COPY I 1920 t-p, _ i*.i t-^-^i i I THE ISSUES I BY SENATOR HARDING AND 1 GOVERNOR COX as§ APACHES, AMERICAN STYLE GRUDGES IN THE PRIZE RING IRELAND ON THE WARPATH OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN LEGION Entered as second-class matter March 24, 1920. at the Post Office at New York, N. T., under Act of March 3. 1879. Price. J2 the year Published weekly by The Legion Publishing Corporation 627 WeBt 43d Street. New York City. Copyright. 1920, by The Legion Publishing Corporation. Net Paid Circulation more than Three-quarters of a Million Copies — These Rugs all full room size, 9 ft.xl2 ft. Very attractive patterns. Brings Splendid Rug Send only one dollar for any one of the four wonderful rug bargains shown above for 30 days' trial in your home. If you are not thoroughly satisfied to keep it, return it to us and we will refund your dollar and pay transportation charges both ways. If you decide to keep rug, take nearly a year to pay. Amazing Rug Bargains It is practically impossible to do justice to these extremely handsome and attractive rugs by mere de- scriptions and cold black and white illustrations such as shown above. That's why we offer to send your choice of any of these four beautiful rugs for 30 days' use in your own home. Read the descriptions care- fully, then make your choice for the 30-day trial test at our risk, Big value in full size 9xl2-foot Ommgrn Af#u *J This is a gold seal "Congoleum" Dmrngm f|fa t "•"5» one-piece Art Rug. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

Creep Through the Decades Legend Has It: Denton’S Retro Cult Classics for Your Halloween Watchlist Haunted History

Thursday, October 31, 2019 Vol. 106, No. 3 TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY Your student newspaper since 1914 Never A Dull Moment N THIS ISSUE HAUNTINGS | CAMP OAKLEY I : How to craft a last minute costume 7 Boo at the U: photo set 3 An introvert’s guide to the perfect HAPPY HALLOWEEN! Halloween night in 7 Graphic by Angelica Monsour. SCARES | HALLOWEEN MOVIES HAUNTS | LOCAL LEGENDS Creep through the decades Legend has it: Denton’s Retro cult classics for your Halloween watchlist haunted history By AMBER GAUDET By ALYSSA WALKER with one of his workers. The work- er was charged with murder, but o October is complete without very town has stories eventually was found not guilty. Na good Halloween movie binge- Eoriginating from years There have been rumors of fest. Even if you’re not into horror, ago that have changed over footsteps and moans being heard the last few decades have offered time, morphing into unset- from the upstairs bedroom, a face plenty of spooky favorites to satisfy tling legends that haunt locals that appears in the attic window your craving for Halloween nostalgia. — and Denton is no exception. and a photograph with eyes that 1970s There are some stories that ev- follow you everywhere you walk. In the aftermath of the Manson family ery Dentonite has explored or at The police have even been called killings, the midst of the Vietnam War, least heard of, like the Old Goat- after employees were spooked by and the scandal of Watergate, the ‘70s were man’s Bridge or the purple door on sounds in the house. -

The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of the Lost Decade, Jessica

The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan “Our Fear Has Taken on a Life of its Own”: The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of The Lost Decade, Jessica Balanzategui University of Melbourne, Australia 0168 The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract The monstrous child of Japanese horror film has become perhaps the most transnationally recognisable and influential horror trope of the past decade following the release of “Ring” (Hideo Nakata, 1999), Japan’s most commercially successful horror film. Through an analysis of “Ring”, “The Grudge” (Takashi Shimizu, 2002), “Dark Water” (Nakata, 2002), and “One Missed Call” (Takashi Miike, 2003), I argue that the monstrous children central to J-horror film of the millenial transition function as anomalies within the symbolic framework of Japan’s national identity. These films were released in the aftermath of the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in the early 1990s — a period known in Japan as ‘The Lost Decade’— and also at the liminal juncture represented by the turn of the millennium. At this cultural moment when the unity of national meaning seems to waver, the monstrous child embodies the threat of symbolic collapse. In alignment with Noël Carroll’s definition of the monster, these children are categorically interstitial and formless: Sadako, Toshio, Mitsuko and Mimiko invoke the wholesale destruction of the boundaries which separate victim/villain, past/present and corporeal/spectral. Through their disturbance to ontological categories, these children function as monstrous incarnations of the Lacanian gaze. As opposed to allowing the viewer a sense of illusory mastery, the J- horror monster-child figures a disruption to the spectator’s sense of power over the films’ diegetic worlds. -

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema a Thesis

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jordan G. Parrish August 2017 © 2017 Jordan G. Parrish. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema by JORDAN G. PARRISH has been approved for the Film Division and the College of Fine Arts by Ofer Eliaz Assistant Professor of Film Studies Matthew R. Shaftel Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract PARRISH, JORDAN G., M.A., August 2017, Film Studies The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema Director of Thesis: Ofer Eliaz This thesis argues that Japanese Horror films released around the turn of the twenty- first century define a new mode of subjectivity: “undead subjectivity.” Exploring the implications of this concept, this study locates the undead subject’s origins within a Japanese recession, decimated social conditions, and a period outside of historical progression known as the “Lost Decade.” It suggests that the form and content of “J- Horror” films reveal a problematic visual structure haunting the nation in relation to the gaze of a structural father figure. In doing so, this thesis purports that these films interrogate psychoanalytic concepts such as the gaze, the big Other, and the death drive. This study posits themes, philosophies, and formal elements within J-Horror films that place the undead subject within a worldly depiction of the afterlife, the films repeatedly ending on an image of an emptied-out Japan invisible to the big Other’s gaze. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

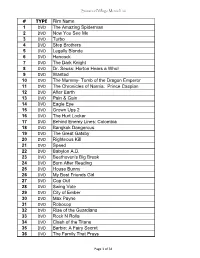

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

Evil in the 'City of Angels'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! April 24 - 30, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 W L M C A B L R G R C S P L N Your Key 2 x 3" ad P E Y S W Z A Z O V A T T O F L K D G U E N R S U H M I S J To Buying D O I B N P E M R Z Y U S A F and Selling! N K Z N U D E U W A R P A N E 2 x 3.5" ad Z P I M H A Z R O Q Z D E G Y M K E P I R A D N V G A S E B E D W T E Z P E I A B T G L A U P E M E P Y R M N T A M E V P L R V J R V E Z O N U A S E A O X R Z D F T R O L K R F R D Z D E T E C T I V E S I A X I U K N P F A P N K W P A P L Q E C S T K S M N T I A G O U V A H T P E K H E O S R Z M R “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lewis (Michener) (Nathan) Lane Supernatural Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Magda (Natalie) Dormer (1938) Los Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Tiago (Vega) (Daniel) Zovatto (Police) Detectives Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Evil in the Peter (Craft) (Rory) Kinnear Murder County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Maria (Vega) (Adriana) Barraza Espionage Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘City of Angels’ for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com Natalie Dormer stars in “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels,” All specials are pre-paid. -

1. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around 2. 10 Things I Hate About You 3

1. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around 2. 10 Things I Hate About You 3. 10,000 BC 4. 101 Dalmatians 5. 102 Dalmations 6. 10th Kingdom 7. 11-11-11 8. 12 Monkeys 9. 127 Hours 10. 13 Assassins 11. 13 Tzameti 12. 13th Warrior 13. 1408 14. 2 Fast 2 Furious 15. 2001: A Space Odyssey 16. 2012 17. 21 & Over 18. 25th Hour 19. 28 Days Later 20. 28 Weeks Later 21. 30 Days of Night 22. 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 23. 300 24. 40 Year Old Virgin 25. 48 Hrs. 26. 51st State 27. 6 Bullets 28. 8 Mile 29. 9 Songs 30. 9 ½ Weeks 31. A Clockwork Orange 32. A Cock and Bull Story 33. A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Christmas 34. A-Team 35. About Schmidt 36. Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 37. Accepted 38. Accidental Spy 39. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective 40. Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls 41. Ace Ventura, Jr. 42. Addams Family 43. Addams Family Reunion 44. Addams Family Values 45. Adventureland 46. Adventures of Baron Munchausen 47. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Christmas Caper 48. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Fun House Mystery 49. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Hotel Who-Done-It 50. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Logical Ranch 51. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Mystery Cruise 52. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the SeaWorld Adventure 53. Adventures of Mary-Kate & Ashley: The Case of the Shark Encounter 54. -

Halloween Hot Spots

Do-it-yourself Horror Film Festival by Jason Soeda Ka ‘Ohana Staff Reporter et’s face it – Halloween in the islands can be a drag if you’re not a kid. You can’t go trick-or-treating and the March of Dimes hasn’t hosted a haunted house in ages. If you’re not into the “costume parties” held in Honolulu dance clubs – where mini-skirts get you in free – what else are you going to do? LIf your answer is stay inside and watch the same monster movie marathon that plays every year, listen up. This year, why not host a horror film festival in the comfort of your own living room? We’ve selected eight blood-curdling flicks from around the world for a night of spine-tingling fun! appy a oween So dim the lights and cozy up to your sweetie. Here’s our list of hair-raising Halloween films, in no particular order: Evil Dead II (1987) Halloween IV (1988) H H ll efore Sam Raimi directed main- he original “Halloween” is the archetypal stream blockbusters like the “Spi- slasher film. It laid the groundwork for “Fri- B T th Halloween Hot Spots der-Man” movies (and way before he day the 13 ” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street.” produced “Xena: Warrior Princess”), he “Halloween IV” is by no means perfect, but it’s by Lauren Shissler made the “Evil Dead” trilogy. For many campy B-movie fun! Michael Myer escapes from Ka ‘Ohana Staff Reporter horror film fans, this is Raimi’s crown- the sanitarium and heads back to Haddonfield, Il- COURTESY IMDB ing achievement. -

Horror Movie Trivia Questions #5

HORROR MOVIE TRIVIA QUESTIONS #5 ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> What kind of monster is the subject of the film "Ginger Snaps"? a. Ghost b. Zombie c. Werewolf d. Vampire 2> Who directed the first Scream movie? a. Drew Barrymore b. John Carpenter c. Wes Craven d. Kevin Williamson 3> In which horror movie would you see the characters John Cooper, Kristen, Dr. Anton Rudolph and Tommy? a. They Nest b. The Thing c. Supernova d. Python 4> Which horror movie stars rapper Snoop Dogg? a. Bones b. The Forsaken c. Arachnid d. The Breed 5> Who directed the horror movie "Ghosts of Mars"? a. John Carpenter b. Victor Salva c. Joe Dante d. Wes Craven 6> Where is the film Wendigo set? a. Siberia b. The Sahara c. New York d. Alaska 7> What kind of evil creature is the subject of the film Wishmaster? a. Demon b. Devil c. Vampire d. Djinn 8> Who stars in the film "Blade"? a. Danny Glover b. Wesley Snipes c. Cuba Gooding Jr. d. Daniel Day Lewis 9> Where is the ghost ship located? a. Sea of Japan b. The Gulf of Mexico c. Bering Sea d. The Mediterranean 10> Which horror film stars Sissy Spacek and Donald Sutherland? a. Anaconda b. 9.56 c. An American Haunting d. Altered 11> Which horror movie starts out during the Salem witch trials? a. Art of the Devil b. The Covenant c. Blessed d. Dark Corners 12> In the 2004 version of the movie "Dawn of the Dead", where do the survivors take refuge? a. -

Resume – August 2021 *COMPLETE RESUME AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST* 2

NANCY NAYOR CASTING Office: 323-857-0151 / Cell: 213-309-8497 E-mail: [email protected] Former SVP Feature Film Casting, Universal Pictures - 10 years THE MOTHER (Feature) NETFLIX Director: Niki Caro Producers: Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas, Benny Medina, Marc Evans, Roy Lee, Miri Yoon Cast: Jennifer Lopez 65 (Feature) SONY PICTURES Writers/Directors: Scott Beck & Bryan Woods Producers: Sam Raimi, Zainab Azizi, Debbie Liebling, Scott Beck, Bryan Woods Cast: Adam Driver, Ariana Greenblatt, Chloe Coleman IVY + BEAN (3 Feature Series) NETFLIX Director: Elissa Down Producers: Anne Brogan, Melanie Stokes Cast: Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Nia Valdalos, Sasha Pieterse, Keslee Blalock, Madison Validum BAGHEAD (Feature) STUDIOCANAL Director: Alberto Corredor Producers: Andrew Rona, Alex Heineman Cast: Freya Allan, Ruby Barker PERFECT ADDICTION (Feature) CONSTANTIN Director: Castille Landon Producers: Jeremy Bolt, Robert Kulzer, Aron Levitz Cast: Kiana Madeira, Ross Butler, Matthew Noszka BARBARIAN (Feature) VERTIGO, BOULDER LIGHT Director: Zach Cregger Producers: Roy Lee, Raphael Margules, JD Lifschitz Cast: Bill Skarsgård, Georgiana Campbell, Justin Long THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF CHARLES ABERNATHY (Feature) NETFLIX Director: Alejandro Brugues Producer: Paul Schiff Cast: Briana Middleton, Rachel Nichols, Austin Stowell, Bob Gunton, David Walton, Peyton List THE COW (Feature) BOULDER LIGHT Director: Eli Horowitz Producers: Raphael Margules, JD Lifschitz Cast: Winona Ryder, Owen Teague, Dermot Mulroney SONGBIRD (Feature) STX/INVISIBLE NARRATIVES/CATCHLIGHT STUDIOS Writer/Director: Adam Mason Producers: Michael Bay, Adam Goodman, Eben Davidson, Jason Clark, Jeanette Volturno, Marcei Brown Cast: Demi Moore, K.J. Apa, Paul Walter Hauser, Craig Robinson, Bradley Whitford, Jenna Ortega, Sofia Carson UMMA (Feature) SONY STAGE 6/CATCH LIGHT STUDIOS Writer/Director: Iris K.