History Happenings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parklane Elementary Global Forest Tree Walk

Parklane Elementary Global Forest Tree Walk LEARNING LANDSCAPES Parklane Elementary Global Forest Tree Walk 2015 Learning Landscapes Site data collected in Summer 2014. Written by: Kat Davidson, Karl Dawson, Angie DiSalvo, Jim Gersbach and Jeremy Grotbo Portland Parks & Recreation Urban Forestry 503-823-TREE [email protected] http://portlandoregon.gov/parks/learninglandscapes Cover photos (from top left to bottom right): 1) Cones and foliage of a monkey puzzle tree. 2) The fall color of a Nothofagus alpina. 3) Cupressus dupreziana in its native range. 4) Students plant and water a young tree. 5) The infl orescence of a Muskogee crape myrtle. 6) Closeup of budding fl owers on a sycoparrotia twig. 7) The brightly-colored fruit of the igiri tree. 8) The fl ower of a Xanthoceras sorbifolium. ver. 1/30/2015 Portland Parks & Recreation 1120 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 1302 Portland, Oregon 97204 (503) 823-PLAY Commissioner Amanda Fritz www.PortlandParks.org Director Mike Abbaté The Learning Landscapes Program Parklane Elementary School The fi rst planting at the Parklane Elementary Global Forest Learning Landscape was in 1999, and since then, the collection has grown to nearly 80 trees. This tree walk identifi es trees planted as part of the Learning Landscape as well as other interesting specimens at the school. What is a Learning Landscape? A Learning Landscape is a collection of trees planted and cared for at a school by students, volunteers, and Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) Urban Forestry staff. Learning Landscapes offer an outdoor educational experience for students, as well as environmental and aesthetic benefi ts to the school and surrounding neighborhood. -

Alexander Von Bunge (1803-1890), Ein Bedeutender Erforscher Der Mongolischen Flora

©Institut für Biologie, Institutsbereich Geobotanik und Botanischer Garten der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Schlechtendalia 25 (2013) Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), ein bedeutender Erforscher der mongolischen Flora Werner HILBIG Zusammenfassung: Hilbig, W. 2013: Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), ein bedeutender Erforscher der mongolischen Flora. Schlechtendalia 25: 3–12. In der vorliegenden Würdigung werden Angaben zur Biographie und Forschungstätigkeit von Alexander von Bunge mitgeteilt. Bunge zählt mit Carl Friedrich von Ledebour und Carl Anton von Meyer zu den bedeutenden frühen Erforschern der Flora Sibiriens. Auf einer 1830–1831 durchgeführten Reise von Sibirien durch die Mongolei nach Peking und zurück konnte Bunge zahlreiche wissenschaftliche Beobachtungen und reiche botanische Auf- sammlungen durchführen, die die Grundlage für Publikationen bildeten. Bunge wurde durch diese Reise zu einem der ersten Erforscher der mongolischen Flora. Er bearbeitete typische Gattungen aus dem sibirisch-mongolischen Raum und beschrieb zahlreiche Pflanzenarten. Von 1836 bis 1867 war er Direktor des Botanischen Institutes an der Universität Dorpat und hielt engen Kontakt mit Diederich Franz Leonhard von Schlechtendal in Halle (Saale) durch Briefwechsel, Publikationen in der Zeitschrift Linnaea und Tausch von Herbarmaterial. Eine Liste mit wichtigen Publikationen von Bunge ist beigefügt. Abstract: Hilbig, W. 2013: Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), an outstanding explorer of the Mongolian flora. Schlechtendalia 25: 3–12. The present appreciation includes information on the biography and research activities of Alexander von Bunge. Bunge belongs together with Carl Friedrich von Ledebour and Carl Anton von Meyer to the outstanding early investigators of the Siberian flora. During a journey from Siberia through Mongolia to Bejing (1830–1831) and back, he made numerous scientific observations and collected rich botanical specimens, which were the basis for his publications. -

Karl Ernst Von Baer Genesis of Ground Ice First Soil Temperature Studies In

Early investigations of permafrost in Siberia by Baltic-German and German scientists Diedrich Fritzsche1 ([email protected]) and Erki Tammiksaar2 1Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Potsdam, Germany 2University of Tartu, Faculty of Science and Technology, Estonia In the 18th and 19th centuries several (1815-1894) traveled through Siberia German and Baltic-German scientists collecting information about the flora, investigated almost unknown territories fauna, geology, climate, ethnology, Karl Ernst von Baer of the Russian Empire. Many of them were history and economy of the Far East of invited by Russian emperors and some Russia. Their results were mostly b e c a m e a c a d e m i c i a n s o f t h e S t . published in journals of the Russian Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876) the expedition to North and East Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Geographical Society. Information about was a Baltic-German naturalist Siberia by A. Th. von Middendorff. German naturalists like Georg Wilhelm Russia became available in Europe and member of the St. Petersburg The main task was to investigate Steller (1709-1746), Johann Georg Gmelin through special journals edited by Academy of Sciences. Between permafrost thickness, tempera- (1709-1755), Peter Simon Pallas (1741- Germans such as P.S. Pallas [1], J.G. 1838 and 1843 he collected all data ture and distribution [15]. Baer available on Siberian ever frozen drew the first permafrost map of 1811), Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876), Georgi [2], Th. Fr. Ehrmann [3], A. Erman ground. He wrote a special per- Siberia (below). -

Carnets Botaniques [email protected]

Astragalus barnassari Grossh. (sect. Trachycercis Bunge), espèce nouvelle pour la flore de Turquie Philippe Rabaute (1) & Pierre Coulot (2) (1) 60 rue du Salet, F-34570 Vailhauquès Carnets botaniques [email protected] ISSN 2727-6287 – Article n°5 – 2020 (2) 9 avenue des Cévennes, Vérargues, F-34400 Entre-Vignes DOI : https://doi.org/10.34971/x5kp-3848 [email protected] Résumé Astragalus barnassari Grossh., espèce acaule de la section Trachycercis Bunge, a été découverte pour la première fois dans l’est de la Turquie, dans la province d’Agri, en 2009. Ce taxon, présent non loin de là dans le nord de l’Iran et en Azerbaïdjan, n’avait jamais été cité avec certitude en Turquie, e malgré une mention imprécise d’Aucher-Éloy au début du XIX siècle. Abstract Astragalus barnassari Grossh., stemless species from the Trachycercis Bunge section, was discovered for the first time in eastern Turkey, in the province of Agri, in 2009. This taxon, present not far from there in the north of Iran and Azerbaijan, had never been cited with certainty in Turkey, despite an imprecise quote from Aucher-Éloy in the early 19th century. Astragalus barnassari Grossh., espèce de la section Trachycercis Bunge, n’a jamais été observée de Turquie. Tout au plus, une mention très imprécise de Aucher laissait le doute planer sur sa présence. Nous l’avons trouvée dans la province d’Agri, à quelques kilomètres de la frontière iranienne, lors de notre voyage en juin 2009. Cette plante s’ajoute à la longue liste des astragales de le flore de Turquie. -

Suaeda Corniculata (Chenopodiaceae) and Related New Taxa from Eurasia

Willdenowia 38 – 2008 81 MARIA LOMONOSOVA, RONNY BRANDT & HELMUT FREITAG Suaeda corniculata (Chenopodiaceae) and related new taxa from Eurasia Abstract Lomonosova, M., Brandt, R. & Freitag, H.: Suaeda corniculata (Chenopodiaceae) and related new taxa from Eurasia. – Willdenowia 38: 81-109. – ISSN 0511-9618; © 2008 BGBM Berlin-Dahlem. doi:10.3372/wi.38.38105 (available via http://dx.doi.org/) The name of the hitherto widely circumscribed species Suaeda corniculata is lectotypified by a speci- men from the Altai and the species subdivided into two subspecies, with the new subsp. mongolica be- ing tetraploid and restricted to SE Siberia and C Asia. Based on morphological, caryological and molecular data, the three new species S. tuvinica, S. kulundensis and S. sibirica are separated from S. corniculata and discussed with regard to their origin. S. tuvinica (2n = 54) is endemic to northern C Asia and southernmost Siberia; S. kulundensis (2n = 72, 90), from SE Europe to W Siberia, has arisen by allopolyploidy from S. corniculata (2n = 36, 54) and S. salsa (2n = 36); S. sibirica (2n = 72), from C to E Siberia and northern C Asia, is an allopolyploid offspring of S. corniculata and an extinct taxon related to S. heteroptera (2n = 18). Dot maps for the total distribution of the new taxa and a new key for all taxa of the S. corniculata group in Eurasia are provided. Additional key words: allopolyploidy, lectotypification, phylogeny, reticulate evolution, taxonomy. Introduction The hitherto widely circumscribed Suaeda corniculata (C. A. Mey.) Bunge is an annual halophyte that grows in forest-steppe, steppe and semidesert areas on soda or chloride solonchaks flooded in spring and drying out at various degrees during summer and autumn. -

Võõrana Omade Hulgas: Gustav Piers Von Bunge Ja Baltisaksa Karskustöö

ÜLEVAADE Võõrana omade hulgas: Gustav Piers von Bunge ja baltisaksa karskustöö Ken Kalling1, Erki Tammiksaar2 Eesti Arst 2015; 19. sajandi lõpukümnendil kogus eesti ühiskonnas hoogu karskusliikumine. Sama ei saa 94(8):484–489 öelda kohaliku eliidi – baltisakslaste – kohta. Sakste tõrksus on tähelepanuväärne kas Saabunud toimetusse: või seetõttu, et nende hulgast võrsus üks eelmise sajandivahetuse juhtivaid meditsiini- 09.12.2014 Avaldamiseks vastu võetud: lise karskustöö propageerijaid Gustav Piers von Bunge, kes suurema osa oma elust veetis 13.01.2015 Šveitsis Baseli ülikoolis. Bunge püüdis ka oma kodumaal progressiivseid tervishoiuideid Avaldatud internetis: 30.09.2015 propageerida, tuues baltisakslastele eeskujuks eestlasi ja lätlasi. Esialgu võtsid kars- kusidee omaks baltisaksa naised. Esimese maailmasõja eelõhtul hakkas siiski ka kohalik 1 TÜ tervishoiu instituut, 2 TÜ ökoloogia ja saksa soost arstkond teemale enam tähelepanu pöörama, jäädes siiski Bungega võrreldes maateaduse instituut mõõdukamale seisukohale, mille kohaselt on alkoholitarvitamise üle otsustamine iga Kirjavahetajaautor: indiviidi isiklik valik. Baltisakslaste tõrksus karskustöö suhtes lähtus majanduslikust Ken Kalling kahjulikkusest nende ringkonnale (riiklik viinamonopol kaotas kõrtsidepidamise õiguse), [email protected] eriti aga karskusliikumise politiseeritusest. Siin oli oluline roll eesti karskusliikumisel. Märksõnad: karskusliikumine, Gustav Karskustöö tähtsusest sajanditagusele eestlust perre. Pärast arsti- ja keemiaõpinguid Tartus Piers von Bunge, nn parajuslus ja täiskarskus kujundavale seltsiliikumisele on kirjutatud töötas ta aastail 1874–1885 Tartus füsioloogia alkoholivastases võitluses korduvalt (1, 2). Tähelepanu on juhitud ka dotsendina, olles muu hulgas Nikolai Lunini karskusaate tähtsusele kohalikus meditsiini- (1853–1937) teaduslik juhendaja ning sel moel loos, selle kohale eesti eugeenilise ideoloogia Tartu meditsiiniloos oluline tegelane kui üks sünnis (3), samuti sõjaeelse eesti arstkonna võimalik vitamiinide teooriale alusepanija (7). osalemisele karskustöös (4). -

Bibliographia Phytosociologica Et Floristica Mongolia: Pars IV Werner Hilbig Petershausen, Germany

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2016 Bibliographia phytosociologica et floristica Mongolia: Pars IV Werner Hilbig Petershausen, Germany Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Hilbig, Werner, "Bibliographia phytosociologica et floristica Mongolia: Pars IV" (2016). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 164. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hilbig in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei (2016) band 13: 83-122. Copyright 2016, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle Wittenberg, Halle (Saale). Used by permission. Erforsch. biol. Ress. Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 2016 (13): 83-122 Bibliographia phytosociologica et floristica Mongolia1 Pars IV W. Hilbig Abstract In Ergänzung zu den bisherigen drei Teilen der Bibliographie vegetationskundlicher, vegeta- tionsökologischer, floristischer und pflanzengeographischer Arbeiten über die Mongolei wird in dieser Arbeit Teil IV der Bibliographie vorgelegt. Er umfasst im Wesentlichen den Zeitraum 2007 bis 2014. Auch Publikationen zur Vegetationsgeschichte und zum botanischen Naturschutz wer- den berücksichtigt. -

Latin for Gardeners: Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored

L ATIN for GARDENERS ACANTHUS bear’s breeches Lorraine Harrison is the author of several books, including Inspiring Sussex Gardeners, The Shaker Book of the Garden, How to Read Gardens, and A Potted History of Vegetables: A Kitchen Cornucopia. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 © 2012 Quid Publishing Conceived, designed and produced by Quid Publishing Level 4, Sheridan House 114 Western Road Hove BN3 1DD England Designed by Lindsey Johns All rights reserved. Published 2012. Printed in China 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Lorraine. Latin for gardeners : over 3,000 plant names explained and explored / Lorraine Harrison. pages ; cm ISBN 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN (invalid) 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) 1. Latin language—Etymology—Names—Dictionaries. 2. Latin language—Technical Latin—Dictionaries. 3. Plants—Nomenclature—Dictionaries—Latin. 4. Plants—History. I. Title. PA2387.H37 2012 580.1’4—dc23 2012020837 ∞ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). L ATIN for GARDENERS Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored LORRAINE HARRISON The University of Chicago Press Contents Preface 6 How to Use This Book 8 A Short History of Botanical Latin 9 Jasminum, Botanical Latin for Beginners 10 jasmine (p. 116) An Introduction to the A–Z Listings 13 THE A-Z LISTINGS OF LatIN PlaNT NAMES A from a- to azureus 14 B from babylonicus to byzantinus 37 C from cacaliifolius to cytisoides 45 D from dactyliferus to dyerianum 69 E from e- to eyriesii 79 F from fabaceus to futilis 85 G from gaditanus to gymnocarpus 94 H from haastii to hystrix 102 I from ibericus to ixocarpus 109 J from jacobaeus to juvenilis 115 K from kamtschaticus to kurdicus 117 L from labiatus to lysimachioides 118 Tropaeolum majus, M from macedonicus to myrtifolius 129 nasturtium (p. -

Alexander Von Bunge (1803-1890), Ein Bedeutender Erforscher Der Mongolischen Flora

Schlechtendalia 25 (2013) Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), ein bedeutender Erforscher der mongolischen Flora Werner HILBIG Zusammenfassung: Hilbig, W. 2013: Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), ein bedeutender Erforscher der mongolischen Flora. Schlechtendalia 25: 3–12. In der vorliegenden Würdigung werden Angaben zur Biographie und Forschungstätigkeit von Alexander von Bunge mitgeteilt. Bunge zählt mit Carl Friedrich von Ledebour und Carl Anton von Meyer zu den bedeutenden frühen Erforschern der Flora Sibiriens. Auf einer 1830–1831 durchgeführten Reise von Sibirien durch die Mongolei nach Peking und zurück konnte Bunge zahlreiche wissenschaftliche Beobachtungen und reiche botanische Auf- sammlungen durchführen, die die Grundlage für Publikationen bildeten. Bunge wurde durch diese Reise zu einem der ersten Erforscher der mongolischen Flora. Er bearbeitete typische Gattungen aus dem sibirisch-mongolischen Raum und beschrieb zahlreiche Pflanzenarten. Von 1836 bis 1867 war er Direktor des Botanischen Institutes an der Universität Dorpat und hielt engen Kontakt mit Diederich Franz Leonhard von Schlechtendal in Halle (Saale) durch Briefwechsel, Publikationen in der Zeitschrift Linnaea und Tausch von Herbarmaterial. Eine Liste mit wichtigen Publikationen von Bunge ist beigefügt. Abstract: Hilbig, W. 2013: Alexander von Bunge (1803-1890), an outstanding explorer of the Mongolian flora. Schlechtendalia 25: 3–12. The present appreciation includes information on the biography and research activities of Alexander von Bunge. Bunge belongs together with Carl Friedrich von Ledebour and Carl Anton von Meyer to the outstanding early investigators of the Siberian flora. During a journey from Siberia through Mongolia to Bejing (1830–1831) and back, he made numerous scientific observations and collected rich botanical specimens, which were the basis for his publications. -

Modern Wolves Trace Their Origin to a Late Pleistocene Expansion from Beringia”

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION FOR LOOG ET AL. 2017 “MODERN WOLVES TRACE THEIR ORIGIN TO A LATE PLEISTOCENE EXPANSION FROM BERINGIA” S1 – ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND AND SAMPLE INFORMATION 2 1.1 PALEONTOLOGICAL HISTORY OF GREY WOLVES 2 1.2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE DESCRIPTIONS 7 ARMENIA 7 BELGIUM 7 CZECH REPUBLIC 10 SWITZERLAND 10 RUSSIA 11 S2 – DNA EXTRACTION, SEQUENCING AND BIOINFORMATICS. 23 2.1 DNA EXTRACTIONS 23 2.2 LIBRARY PREPARATION 24 2.3 SEQUENCE GENERATION 27 2.4 RAW SEQUENCE DATA PROCESSING 28 2.5. MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF NEWLY GENERATED, ANCIENT SEQUENCES 30 Table S2 31 Figure S1 32 Figure S2 33 S3 – DATA ANALYSES & RESULTS 36 3.1 BEAST ANALYSES & RESULTS 36 PARTITION FINDER 36 Table S3 36 MUTATION RATE CALCULATION 37 INPUT FILE SETTINGS 37 PRIORS 38 MCMC CHAIN 38 BEAST RESULTS 38 Table S4 39 Table S5 39 3.2 SPATIAL MODELLING RESULTS 39 Table S6 39 Table S7 40 Table S8 40 3.3 SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES 42 Figure S3 42 Figure S4 43 Figure S5 44 Figure S6 45 Figure S7 46 Figure S8 47 Figure S9 48 Figure S10 49 Figure S11 50 Figure S12 51 Figure S13 52 Figure S14 53 Figure S15 54 Figure S16 55 1 S1 – Archaeological Background and Sample Information 1.1 Paleontological history of grey wolves Grey wolves (Canis lupus) are a highly adaptable species, able to live in a range of environments and with a wide natural distribution. Studies of modern grey wolves have found distinct subpopulations living in close proximity (Musani et al., 2007; Schweizer et al., 2016). This variation is closely linked to differences in habitat - specifically precipitation, temperature, vegetation, and prey specialization, which particularly affect cranio-dental plasticity (Geffen et al., 2004; Pilot et al., 2006; Flower and Schreve, 2014; Leonard, 2015). -

The Open Door

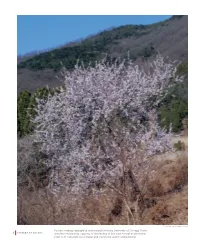

Photo Credit: Ye Jianfei and Dr Liu Bo You are reading copyrighted material published by University of Chicago Press. 8 FATHERS OF BOTANY Unauthorized posting, copying, or distributing of this work except as permitted under U.S. copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. chapter 2 The Open Door In ornamental trees, shrubs, and herbs, suitable for outdoor cultivation in the British Isles, China is the richest country in the world. Our indebtedness to China may in a measure be realised if an imaginary attempt be made to expunge from our gardens all the plants she has given us. 1 E. H. WILSON he first and most famous of the missionaries to inves- father on visits to patients in the surrounding countryside, look- Ttigate the botany of China in the nineteenth century was ing, listening, asking questions and discussing everything he Père Armand David, one of the most accomplished naturalists was told, eager to discover the laws which governed the won- ever to visit the Far East. As well as collecting a multitude of ders of nature which he saw around him. At school, he proved new plant species during his extensive journeys into unexplored an outstanding pupil, devoting himself to languages, especially areas of China, he also discovered new birds, mammals, rep- to Latin – the language of scientific description – and to natural tiles and insects. He kept comprehensive journals in which he sciences such as botany, ornithology and entomology. He noted noted in fascinating detail the minutiae of his journeys. Colour- later that it was some years before he understood what his fel- ful descriptions of the people he met, the places he stayed and low pupils found to enjoy in books other than the volumes of the food he ate were accompanied by precise details of the geo- natural history with which he filled his own spare time.2 logical changes in the landscape and soil, together with notes on some of his most remarkable zoological and botanical finds. -

Imperial Science Im Zarenreich.Htm

Herausgeber: Nordost-Institut, Institut für Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen in Nordost- europa e. V., an der Universität Hamburg, Conventstraße 1, 21335 Lüneburg, Lüneburg 2015. URL: http://www.ikgn.de/online-publikationen/mark_imperial science im zarenreich.htm Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Online-Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Dieses Werk unterliegt dem deutschen Urheberrecht und ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bear- beitungen 4.0 International Lizenz. Sie dürfen das Werk vervielfältigen, verbreiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen zu den folgenden Bedingungen: - Namensnennung. Sie müssen den Namen des Autors/Rechteinhabers in der von ihm fest gelegten Weise nennen. - Keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Dieses Werk darf nicht für kommerzielle Zwecke verwendet werden. - Keine Bearbeitung. Wenn Sie das Material remixen, verändern oder darauf anderweitig direkt aufbauen, dürfen Sie die bearbeitete Fassung des Materials nicht verbreiten. Diese Lizenz lässt die Urheberpersönlichkeitsrechte des Autors unberührt. Empfohlene Zitierweise: Mark, Rudolf A.: Imperial Science im Zarenreich. Die Rolle deutscher und russländischer Gelehrter bei der Expansion Russlands nach Zentralasien seit Peter I. (Online-Publikationen des Nordost-Instituts/Forschungsbeiträge), Lüneburg 2015, URL: www.ikgn.de/online-publikationen/mark_imperial