Identity Fonnation: Women's Magazine Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM OCTOBER 4TH 2018-1.Xlsx

CINEMA AUGUSTA PROGRAM COMING ATTRACTIONS BELOW or VISIT OUR WEB PAGE PHONE 86422466 TO CHECK SESSION TIMES www.cinemaaugusta.com MOVIE START END PAW PATROL MIGHTY PUPS (G) Oct 4th Thu PAW PATROL (G) 12.00pm 12.50pm Max Calinescu, Devan Cohen. SMALLFOOT (G) 1.00pm 2.40pm Our favourite pups are back with all new superpowers on CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (G) 2.50pm 4.40pm their biggest mission yet. VENOM (M) 4.50pm 6.50pm The House with Clock in Walls (PG) 7.00pm 8.40pm JOHNNY ENGLISH STRIKES AGAIN (PG) VENOM (M) 8.50pm 10.45pm Rowan Atkinson. After a cyber‐attack reveals the identity of all of the active Oct 5th Fri PAW PATROL (G) 10.30am 11.20am undercover agents in Britain, Johnny English is forced to come TEEN TITANS GO (PG) 11.30am 1.00pm out of retirement to find the mastermind hacker. The House with Clock in Walls (PG) 1.10pm 3.00pm THE MERGER (M) VENOM (M) 3.10pm 5.10pm Damian Callinan, John Howard, Kate Mulvany. SMALLFOOT (G) 5.20pm 7.00pm Troy Carrington, a former professional football player returns THE MERGER (M) 7.10pm 8.50pm to his country town after an abrupt end to his sporting career VENOM (M) 9.00pm 11.00pm and is persuaded to coach the hapless local footy team, the Roosters. Oct 6th Sat SMALL FOOT (G) 10.30am 12.10pm VENOM (M) VENOM (M) 12.20pm 2.20pm Tom Hardy, Michelle Williams. PAW PATROL (G) 2.30pm 3.20pm TEEN TITANS GO (PG) 3.30pm 5.00pm When Eddie Brock acquires the powers of a symbiote, he will CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (G) 5.10pm 7.00pm have to release his alter‐ego Venom to save his life. -

Katya Thomas - CV

Katya Thomas - CV CELEBRITIES adam sandler josh hartnett adrien brody julia stiles al pacino julianne moore alan rickman justin theroux alicia silverstone katherine heigl amanda peet kathleen kennedy amber heard katie holmes andie macdowell keanu reeves andy garcia keira knightley anna friel keither sunderland anthony hopkins kenneth branagh antonio banderas kevin kline ashton kutcher kit harrington berenice marlohe kylie minogue bill pullman laura linney bridget fonda leonardo dicaprio brittany murphy leslie mann cameron diaz liam neeson catherine zeta jones liev schreiber celia imrie liv tyler chad michael murray liz hurley channing tatum lynn collins chris hemsworth madeleine stowe christina ricci marc forster clint eastwood matt bomer colin firth matt damon cuba gooding jnr matthew mcconaughey daisy ridley meg ryan dame judi dench mia wasikowska daniel craig michael douglas daniel day lewis mike myers daniel denise miranda richardson deborah ann woll morgan freeman ed harris naomi watts edward burns oliver stone edward norton orlando bloom edward zwick owen wilson emily browning patrick swayze emily mortimer paul giamatti emily watson rachel griffiths eric bana rachel weisz eva mendes ralph fiennes ewan mcgregor rebel wilson famke janssen richard gere geena davis rita watson george clooney robbie williams george lucas robert carlyle goldie hawn robert de niro gwyneth paltrow robert downey junior harrison ford robin williams heath ledger roger michell heather graham rooney mara helena bonham carter rumer willis hugh grant russell crowe -

Octnovscope2020

SCOPE FAIRVIEW PARK SENIOR LIFE OFFICE NEWSLETTER Mayor Patrick J. Cooney October & November 2020 20769 Lorain Road Fairview Park, OH 44126 440-356-4437 Welcome back! This month, we welcome Autumn with its cooler temperatures and changing of the leaves. One of the biggest changes we are looking forward is being able to open our building on Monday, October 19th for limited in person programs. Your safety is our first priority and we encourage you to call us with any questions about our reopening guidelines. We will not be serving coffee or congregate lunches until further notice. All activities with be limited to 10 people or less and preregistration is required for every program. Masks are required for all participants. As we begin this first phase of reopening, our hours will be reduced to implement sanitizing procedures. New Senior Center hours starting Monday, October 19th will be: Monday/Tuesday/Friday from 9:00am-3:00pm. Flu Vaccine Clinic Marc’s Pharmacy will be administering high-dose flu vaccines on Thursday, October 22nd from 10:00am-1:00pm. Appointments are required. Please arrive no more than 5 minutes before your scheduled time and don’t forget your Medicare card! Silver Sneakers We will offer Silver Sneakers exercise classes Mondays at 10:30 am and Fridays at 12:00 pm. Class size is limited to 10 people or less. Preregistration is required. Participants should arrive no more than 10 minutes prior to class and bring their own water bottle. Computer Lab & Library Lending On Mondays and Fridays at noon we will take Virtual & Phone Bingo reservations for our (socially distanced) computer Come join the games on Mondays at 12:00 pm and lab and book lending library. -

12Th National A&E Journalism Awards

Ben Mankiewicz Tarana Burke Danny Trejo Quentin Tarantino The Luminary The Impact Award The Visionary The Distinguished Award Award Storyteller Award 2019 TWELFTH ANNUAL Ann-Margret The Legend Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB 12TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards A Letter From the Press Club President Good evening and welcome to the 12th annual National Arts & Entertain- ment Journalism Awards. Think about how much the entertainment industry has changed since the Press Club introduced these awards in 2008. Arnold Schwarzenegger was our governor, not a Terminator. Netflix sent you DVDs in the mail. The iPhone was one year old. Fast forward to today and the explosion of technology and content that is changing our lives and keeping journalists busy across the globe. Entertainment journalism has changed as well, with all of us taking a much harder look at how societal issues influence Hollywood, from workplace equality and diversity to coverage of political events, the impact of social media and U.S.-China rela- tions. Your Press Club has thrived amid all this. Participation is way up, with more Chris Palmeri than 600 dues-paying members. The National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards have grown and changed as well. Tonight we’re in a ballroom in the Millennium Biltmore Hotel, but in 2008 the awards took place in the Steve Allen Theater, the Press Club’s old home in East Hollywood. That building has since been torn down. Our first event in 2008 featured a cocktail party with no host and only 111 entries in the competition. -

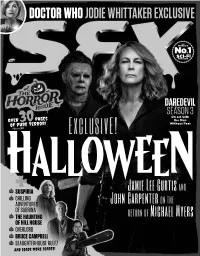

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Golden Globes Ballot Watch Live Sunday on Nbc Coverage Begins at 7Et/4Pt

2016 GOLDEN GLOBES BALLOT WATCH LIVE SUNDAY ON NBC COVERAGE BEGINS AT 7ET/4PT Best Motion Picture, Best Actress Motion Picture, Best Actor Motion Picture, Best Motion Picture, Drama Drama Drama Musical or Comedy Carol Cate Blanchett, Carol Bryan Cranston, Trumbo The Big Short Mad Max: Fury Road Brie Larson, Room Leonardo DiCaprio, The Revenant Joy The Revenant Rooney Mara, Carol Michael Fassbender, Steve Jobs The Martian Room Saoirse Ronan, Brooklyn Eddie Redmayne, The Danish Girl Spy Spotlight Alicia Vikander, The Danish Girl Will Smith, Concussion Trainwreck Best Actress Motion Picture, Best Actor Motion Picture, Best Motion Picture, Best Motion Picture, Musical or Comedy Musical or Comedy Animated Foreign Language Jennifer Lawrence, Joy Christian Bale, The Big Short Anomalisa The Brand New Testament Melissa McCarthy, Spy Steve Carell, The Big Short The Good Dinosaur The Club Amy Schumer, Trainwreck Matt Damon, The Martian Inside Out The Fencer Maggie Smith, The Lady in the Van Al Pacino, Danny Collins The Peanuts Movie Mustang Lily Tomlin, Grandma Mark Ruffalo, Infinitely Polar Bear Shaun the Sheep Movie Son of Saul Best Supporting Actress, Best Supporting Actor, Best Director, Best Screenplay, any Motion Picture any Motion Picture Motion Picture Motion Picture Jane Fonda, Youth Paul Dano, Love & Mercy Todd Haynes, Carol Emma Donoghue, Room Jennifer Jason Leigh, The Hateful Eight Idris Elba, Beasts of No Nation Alejandro Iñárritu, The Revenant Tom McCarthy, Josh Singer, Spotlight Helen Mirren, Trumbo Mark Rylance, Bridge of Spies Tom -

Happy Mother's

Thank you Mom For everything you do and for your never ending love. You are so very special and a true blessing from above. So with all my heart I want to say I love you Mom, Happy Mother’s Day To All the Mothers, THE MOMMY SONG VIDEO: We have put together a special A fun song that we know all moms can relate. package just for you to help make Sung to the William Tell Overture! your day as special as you. Click below on link below https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OuqI6gcZpJA ENTER TO WIN A MOTHER’S DAY PRIZE: MOVIES FOR MOM: Email your name, address, phone Freaky Friday: Jamie Lee Curtis plays a single mom who strug- gles to maintain a healthy relationship with her teenage daughter. number along with how many After receiving magical fortune cookies from a Chinese restaurant, children you have. We will draw the two wake up to find out they've switched bodies. Popcorn the winner and announce it in movie gold. Friday’s E-blast! Please, only one Cheaper By The Dozen: A classic family comedy, Cheaper by entry per mom. Send to the Dozen will not disappoint. The movie follows parents who [email protected] have sacrificed a lot to raise twelve children. When the mother, Kate (Bonnie Hunt), goes on tour for her recently published par- Deadline: Friday, May 8th, enting memoir, Tom (Steve Martin) is left to parent the dozen kids 10:00 a.m. on his own. We will contact the winner via Because I Said So: This list is heavy on the Diane Keaton (as it e-mail & phone. -

Demi Lovato @Ddlovato Society Demonizes Food Too Much. Just Remember, It’S Okay to Eat Things Like Cheese, Flour and Even Sugar in Moderation

14 Monday, January 15 , 2018 Monday, January 15, 2018 15 Demi Lovato @ddlovato Society demonizes food too much. Just remember, it’s okay to eat things like cheese, flour and even sugar in moderation. #ihadwhitebreadtodayandLOVEDit Los Angeles ollywood actor Idris Elba had fun directing his first movie ‘Yardie’, but it was more difficultH than he expected. “I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to direct this material, with which I can identify quite a bit. The story takes place in London and Jamaica, and it’s based on the novel (Victor Headley’s ‘Yardie’), which was popular urban fiction in the 1980s and 1990s,” Elba told Psychologies magazine, reports femalefirst. ilmmaker James Cameron has praised co.uk. Factress Eliza Dushku’s bravery for He added: “It’s been a lot of fun but the hardest Los Angeles speaking up against stunt co-ordinator Joel thing I’ve done. I never realised how difficult it ctor Mark Wahlberg has Kramer for sexual misconduct. was going to be, but I loved it and getting to donated $1.5 million to the On Saturday, Dushku came forward spend time in Jamaica was phenomenal.” (IANS) Time’sA Up Legal Defence Fund in with the allegations of sexual abuse by the name of his “All the Money in the Kramer while she was working on one of World” co-star Michelle Williams. her earliest roles as the daughter of Arnold The donation comes in response Schwarzenegger and Jamie Lee Curtis in the to criticism over a gender pay gap for 1994 film ‘True Lies’. -

Planning Guide

Planning Guide Brochure sponsored by Another best-in-class convention… Each year when we think about the upcoming MCAA convention, we ask ourselves, can it get any better? What could be left to experience, to enjoy? For starters, you will be inspired and informed by world-class major session speakers: Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski of MSNBC, adventurer Erik Weihenmayer, former FBI Director Robert S. Mueller and actress Jamie Lee Curtis. There’s our impressive slate of featured session speakers and seminar presenters, including business strategists and industry specialists covering a gamut of topics of importance to our membership. And then, there are the many opportunities to network with your peers, enjoy great sporting and social events, visit with our manufacturer and supplier partners, and rock out to one of America’s top pop rock bands—Train! My commitment to you is that this year MCAA’s convention will—yet again—exceed expectations! It will be an extraordinary event you won’t want to miss! Michael R. Cables MCAA President …with a very special moment. This year’s Opening Session will include a very special moment for our association. I will be presenting our Distinguished Service Award to MCAA member John Odom. John and I served together on CPMCA’s Board of Directors. I personally know of his many contributions to our association and industry. For these alone he is a worthy recipient of MCAA’s highest award. But this year, coming back to his family, his friends and his company from horrific, near-fatal injuries sustained in the Boston Marathon bombing, John has given new meaning to the expression “exceed expectations.” His incredible journey, with his wife Karen always at his side, has inspired us all—and it will be my privilege to bestow this award on him in Scottsdale. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Thanks Atlanta Mcdreamy Grey’S Anatomy and Scandal, One for Voting Us As Atlanta’S Best Art Supply Store of the Most Fun Shows on TV

TV Station Control TRASH IS THE NEW ART BY BENJAMIN CARR Lady GaGa in American RITER-PRODUCERS OF THE Horror Story: Hotel bygone era whose names were synonymous with quality television: WNorman Lear (All in the Family), James L. Brooks (The Simpsons, Mary Tyler Moore), Stephen Bochco (L.A. Law, NYPD Blue), David E. Kelley (Picket Fences, Ally McBeal), David Simon (Homicide, The Wire) and David Chase (The Sopranos) have been replaced with the likes of Shonda Rhimes and Ryan Murphy. With today’s producers, what we get in terms of quality feels more like grand trash than great art. But the most addictive, reliable TV has always been that. Rhimes powerhouse hits are long in the tooth but still watchable even though they killed Thanks Atlanta McDreamy Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal, one For Voting Us As Atlanta’s Best Art Supply Store of the most fun shows on TV. Murphy has been for 4 Consecutive Years! churning out lots of mostly hit shows since Nip/Tuck. His shows are generally oversexed, SERVING ATLANTA FROM TWO CONVENIENT LOCATIONS musical, nutty affairs that concentrate on style and shock first, logic and plot almost never. BUCKHEAD PONCE CITY MARKET Shows like Nip/Tuck and Glee are usually good held even the weakest of plots together with sheer 3330 Piedmont Rd, Suite 18 650 North Ave NE, Suite 102 for a season or two, then they spectacularly verve. In her place, Murphy has given us Lady Atlanta, GA 30305 Atlanta, GA 30308 implode or just go completely off the rails, but Gaga, who in a couple uncomfortable episodes 404.237.6331 404.682.6999 never stop. -

Bamcinématek Presents Vengeance Is Hers, a 20-Film Showcase of Some of Cinema’S Most Unforgettable Heroines and Anti-Heroines, Feb 7—18

BAMcinématek presents Vengeance is Hers, a 20-film showcase of some of cinema’s most unforgettable heroines and anti-heroines, Feb 7—18 Includes BAMcinématek’s ninth annual Valentine’s Day Dinner & a Movie, with a screening of The Lady Eve and dinner at BAMcafé The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Jan 10, 2014—From Friday, February 7 through Tuesday, February 18, BAMcinématek presents Vengeance is Hers. From screwball proto-feminism to witchy gothic horror to cerebral auteurist classics, this 20-film series gathers some of cinema’s most unforgettable heroines and anti-heroines as they seize control and take no prisoners. Seen through the eyes of some of the world’s greatest directors, including female filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman and Kathryn Bigelow, these films explore the full gamut of cinematic retribution in all its thrilling, unnerving dimensions. Vengeance is Hers is curated by Nellie Killian of BAMcinématek and Thomas Beard of Light Industry. Opening the series on Friday, February 7 is Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea (1969), a film adaptation of the Euripides tragedy which follows the eponymous sorceress on a vicious crusade for revenge. Starring legendary opera singer Maria Callas in her first and only film role, Medea marks the final entry in Pasolini’s “Mythical Cycle” which also includes Oedipus Rex (1967), Teorema (1968), and Porcile (1969). “Brilliant and brutal” (Vincent Canby, The New York Times), Medea kicks off this series showcasing international films from a variety of genres and creating an alternate history to the clichéd images of avenging women.