Mixing It up Bent and Twisted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Techno-Punk and Terra-Ism

Making a Noise – Making a Difference: Techno-Punk and Terra-ism GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract This article charts the convergence of post-punk/post-settler logics in the techno-punk development in Australia. Exploring how punk would become implicated in the cultural politics of a settler society struggling for legitimacy, it maps the ground out of which Labrats sound system (and their hybrid outfit Combat Wombat) arose. It provides an entry to punk through an analysis of the concept of hardcore in the context of cultural mobilisations which, following more than two centuries of European colonisation, evince desires to make reparations and forge alliances with Indigenous people and landscape. To achieve this, the article traces the contours and investigates the implications of Sydney’s techno-punk emergence (as seen in The Jellyheads, Non Bossy Posse, Vibe Tribe and Ohms not Bombs), tracking the mobile and media savvy exploits of 1990s DIY sound systems and techno terra-ists, aesthetes and activists adopting intimate and tactical media technologies, committing to independent and decentralised EDM creativity, and implicated in a movement for legitimate presence. Keywords techno, anarcho-punk, hardcore, sound systems, postcolonialism, Sydney techno-punk scene Figure 1: Outback Stack. Photo by Pete Strong Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(2) 2010, 1-28 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2010 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ 2 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 2 Making a Difference “Why do they keep calling our generation, generation x, when actually we’re genera- tion y?... Why? Because we’re the one’s asking the questions”. -

BIO Andrew Gilbert Born 1980, Edinburgh, Scotland. Lives And

BIO Andrew Gilbert Born 1980, Edinburgh, Scotland. Lives and works in Berlin Education 1997 - 2002: M.A: (Hons) Fine Art - University of Edinburgh and Edinburgh College of Art Solo Exhibitions (selection) 2019 The Royal Botanical Drawings of Emperor Andrew, Ten Haaf Projects, Amsterdam 2018 The Glorious Opening of Emperor Andrew's Museum, Sperling, Munich Andrew Gilbert solo presentation, Sunday Fair, London, with Sperling Und willst du nicht mein Brueder sein, so schlag ich dir den Schaedel ein - with Martin Neumeier, Botschaft, Berlin 2017 Andrew Gilbert and Sam Durant, Last Tango, Zurich The Sun Will Never Set on the British Empire - The Beast Awakens, Ten Haaf Projects, Amsterdam Andrew's Glorious Occupation of Exotic Bavaria, Filsers, Mainburg Into the Valley of Death - Rode the Six Hundred, Galerie Kai Erdmann, Hamburg 2016 Solo Presentation, ABC Kunst Messe, Berlin, with Sperling Shaka Zulu the Musical - Directed by Andrew, Sperling, Munich Ulundi Is Jerusalem Andrew Is Emperor Brocoli Is Holy, Overbeck - Gesellschaft Museum / St Petri Kirche, Luebeck Emperor Andrew Meets His Waterloo, Superdeals, Brussels 2015 Trophies of the Savages - Idols of Civilisation, Blank Projects, Cape Town, South Africa The Life of Baby Afghan Squirrel, Sperling, Munich European Tribal War Idols, Waterloo 1815, Gallery Polad - Hardouin, Paris Je suis...Brocoli!, Jagla Ausstellungsraum, Koeln Andrew's Exotic and Erotic Massage Parlour, Sightfenster, Koeln 2014 Fiori e Soldati - with M. Galliani, Studio d'Arte Raffaelli, Trento Sacred Soil and Bloody Ground, -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

BIMM Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22

Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22 bimm.ac.uk Contents Welcome Welcome 3 As Principal of BIMM Institute Birmingham, I’m hugely excited to be at the helm of our newest UK college, About Birmingham 4 located at the heart of this vibrant creative and artistic My Birmingham 10 musical city. About BIMM Institute Birmingham 12 At BIMM Institute, we give you an experience of the real BIMM Institute Birmingham Lecturers 16 industry as it stands today – it’s our mission to create BIMM Institute Birmingham Courses 18 a microcosm of the music business within the walls of Location 22 the college. If you’re a songwriter, you’ll find the best musicians to collaborate with; if you’re a guitarist, bassist, Your City 24 drummer or vocalist, you’ll find the best songwriters and Music Resources 28 fellow band members. If you’re a Music Business, Music Production, Event Management or Music Marketing, Media Accommodation Guide 34 and Communication student, you’ll have access to the best Join Us in Birmingham 38 emerging musical talent the city has to offer. BIMM Institute is a hotbed of talent and being a BIMM student means you’ll be part of that community, making many vital connections, which you’ll hopefully keep for the rest of your life and career. The day you walk into BIMM Institute as a freshly enrolled student is the first day of your career. While you’re a BIMM student, you’ll be immersed in the industry. You’ll be taught by current music professionals who bring real, up-to-date experience directly into the classroom, and the curriculum they’re teaching is current and relevant because it constantly evolves with the latest developments in the business. -

E Guide the Travel Guide with Its Own Website

Londonwww.elondon.dk.com e guide the travel guide with its own website always up-to-date d what’s happening now London e guide In style • In the know • Online www.elondon.dk.com Produced by Blue Island Publishing Contributors Jonathan Cox, Michael Ellis, Andrew Humphreys, Lisa Ritchie Photographer Max Alexander Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound in Singapore by Tien Wah Press First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Dorling Kindersley Limited 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL Reprinted with revisions 2006 Copyright © 2005, 2006 Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 4053 1401 X ISBN 978 1 40531 401 5 The information in this e>>guide is checked annually. This guide is supported by a dedicated website which provides the very latest information for visitors to London; please see pages 6–7 for the web address and password. Some information, however, is liable to change, and the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of this book, nor for any material on third party websites, and cannot guarantee that any website address in this book will be a suitable source of travel information. We value the views and suggestions of our readers very highly. Please write to: Publisher, DK Eyewitness Travel Guides, Dorling Kindersley, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, Great Britain. -

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report by Date

STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONAL REGULATION AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report Administrative Actions Taken by the Florida Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco Division 10/12/2016 9:24:36AM 1/1/2013 Through 12/31/2013 Please note that any discipline listed is subject to appeal within 30 days of the issuance of a Final Order. Penalties outside the AB&T Division's guildelines are based upon extensive documented aggravating or mitigating circumstances. Penalties may be reduced based upon the provisions of Sections 561.706 and 569.008, Florida Statutes for an employee's illegal sale or service of alcohol or tobacco to a person who is not of lawful age based upon the licensee's qualification as a responsible vendor. Business Name: #9 FOOD STORE Licensee: NGUYEN, CVA License Number: 5802771 County: Orange Admin Case Number: 2012028583 Date Accepted: 11/19/2012 Disposition: Final Order Violation(s): 1. SELL SINGLE/LOOSE CIGARETTES 2. SALE OF TP TO U/A/P (LICENSEE) Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,11/19/2012; Business Name: (THE) OFFICE Licensee: A & S ENTERTAINMENT LLC License Number: 2301971 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2012049043 Date Accepted: 01/09/2013 Disposition: Stipulation Violation(s): 1. LIQUOR BOTTLES; REFILLING Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,01/09/2013; Business Name: (THE) WINE SHOP OF ST. PETERSBURG BEACH Licensee: (THE) WINE SHOP OF ST. PETERSBURG BEACH, License Number: 6210952 County: Pinellas Admin Case Number: 2013033777 Date Accepted: 11/26/2013 Disposition: Final Order Violation(s): 1. VENDOR TO VENDOR SALES Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,11/26/2013; Business Name: 101 DOWNTOWN Licensee: 101 DOWNTOWN LLC License Number: 1102762 County: Alachua Admin Case Number: 2013025469 Date Accepted: 07/29/2013 Disposition: Stipulation Violation(s): 1. -

Welcome to Magdalen!

Welcome To Magdalen! Freshers’ Handbook 2016 1 Contents 3: A Welcome from your Freshers’ rep 4: Accommodation 6: What to bring 8: Subfusc 9: Finance 10: Your JCR Committee 16: Where to go in Oxford 18: Going out in Oxford 20: Subject Guides 31: Clubs and Societies 39: Jargon Buster 42: A final word from me 2 A Welcome from your Freshers’ Rep Hello and Welcome! You may have already met me via Facebook/ Email but either way I’m Liv Kinsey, your Freshers’ Rep, and I’m here to make your transition from sixth form/ college to Oxford and Magdalen as smooth as possible. I’ll be a source of support, the font of all college and University-related knowledge and I will try to answer as many of your questions as I can. No question is too big, too small, too stupid or too trivial– every person has been in the same situation as you and asked their own Freshers’ Rep some bizarre stuff. This Handbook should answer as many of your questions about life at Magdalen as well as life in Oxford as possible and, hopefully, get you all excited for coming up in October! First of all though, congratulations! You’ve achieved something really amazing. Don’t forget that. There are very few people in this world who can attest to having studied at the University of Oxford, let alone those who can attest to studying at (undoubtedly) the best college in the University. You definitely deserve to feel ex- tremely proud of yourself, you’ve earned it! Secondly, try not to worry too much before you get here. -

Cooked in the Lab Dark, Techy D&B Trio Ivy Lab Break Bad on LP P.108

MUSIC DECEMBER ON THE DANCEFLOOR This month’s tracks played out p. 92 GO LONG! The long-players listened to p. 108 WILD COMBINATION The most crucial compilations p. 113 Cooked In The Lab Dark, techy d&b trio Ivy Lab break bad on LP p.108 djmag.com 091 HOUSE REVIEWS BEN ARNOLD [email protected] melancholy pianos, ‘A Fading Glance’ is a lovely, swelling thing, QUICKIES gorgeously understated. ‘Mayflies’ is brimming with moody, building La Fleur Fred P atmospherics, minor chord pads Make A Move Modern Architect and Burial-esque snatches of vo- Watergate Energy Of Sound cal. ‘Whenever I Try To Leave’ winds 9.0 8.5 it up, a wash of echoing percus- The first lady of Berlin’s A most generous six sion, deep, unctuous vibrations Watergate unleashes tracks from the superb and gently soothing pianos chords. three tracks of Fred Peterkin. It’s all This could lead Sawyer somewhere unrivalled firmness. If great, but ‘Tokyo To special. ‘Make A Move’’s hoover Chiba’, ‘Don’t Be Afraid’, bass doesn’t get you, with Minako on vocals, Hexxy/Andy Butler ‘Result’’s emotive vibes and ‘Memory P’ stand Edging/Bewm Chawqk will. Lovely. out. Get involved. Mr. Intl 7. 5 Various Shift Work A statuesque release from Andy Hudd Traxx Now & Document II ‘Hercules & Love Affair’ Butler’s Mr. Then Houndstooth Intl label. Hexxy is his new project Hudd Traxx 7. 5 with DJ Nark, founder of the excel- 7. 5 Fine work in the lent ‘aural gallery’ site Bottom Part four of four in this hinterland between Forty and Nark magazine. -

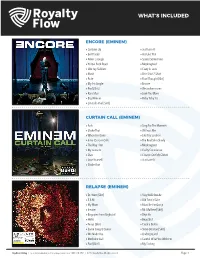

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Assessing the Future Ip Landscape of Music’S Cash Cow: What Happens When the Live Concert Goes Virtual

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\91-2\NYU205.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-MAY-16 12:42 ASSESSING THE FUTURE IP LANDSCAPE OF MUSIC’S CASH COW: WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THE LIVE CONCERT GOES VIRTUAL CHARLES H. LOW* If piracy has been the bane of the music industry, and live performances are a financial buoy, what happens when live performances are ported to a virtual medium that all of a sudden may be subject to piracy again? This Note examines the various intellectual property frameworks through which one can look at the protectable elements of a live show or concert and what happens to the pro- tectability of those elements once the show is ported to virtual reality. Given that technology to date has had a much larger impact on recorded music than on live performances, the introduction of virtual reality technology has serious disruptive potential. This Note argues that one can use existing intellectual property law to weave a complex web of protected elements around less traditional targets of IP like stage, set, and lighting design, background visuals, live performers, and props. This web of intellectual property protection will encourage strong contracting and yield more avenues for resisting piracy in the virtual reality world. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 426 R I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ECONOMIC STATE OF THE MUSIC INDUSTRY, THE NUANCES OF VIRTUAL REALITY, AND TWO VERY MARKETABLE LIVE SHOWS WITH VR POTENTIAL .............................................. 430 R A. “Don’t Let Me Down”: The Current Economic State of the Music Industry ............................... 430 R B. “In Some Ways, the Biggest Competitor . Might Be a Bottle of Wine”: An Introduction to Virtual Reality ............................................. -

Fringe Bar {Rain Cry Recorders | Bankrqbber | Napkin

FRINGE BAR {RAIN CRY RECORDERS | BANKRQBBER | NAPKIN RECORDS | KYLE ipt^lf j lOiL ffi^ IN^17^/7£rfSt/yFF $OUND-OFF IfefEfrEMBER 2013 | That Magazine From CiTR 101.9 FM | Free! | Supportir^ir^^^Snaefe^^^^W9^^;3D Years shindig Shindig flam Tues^ Three tettesMfig bands nightly, and Jokes for Beer. Visit wwwxitrxa/shindtg fw Mi schedule. IMAN&WUTO OUR SPONSORS ms&mm Fader Master Studios Nimbus School of Recording Arts Rain City Recorders NXNI Band Merch Canada Long & McQuade Vogvilie Receding Canadian Musk Week Mint Records Zulu Records MsmtaMagailM Musk Waste UPCOMING 254 East Hastings Street SHOWS WCRSttAW 604 681.8915 O00O0f• REDO KROSS i MIAMI DEVICE DIAMOND HEADS. RAVEN DYING FETUS wiUi Shawn Mzarek Lives! j with Gord Grdina's Haram • with Titan's Eve |J with Exhumed, Devourment, Abiotic, Archspire MOONDOGGIES j WAXTMLOR&THEDUSTY GUITAR WOLF DEERTICK J with The Maldives, The Wild North RAINBOW EXPERIEHK H with The Coathangers and Coward with Robert Ellis WEST OF HELL TWOTO FUCKED UP&TERROR WATAIN with Titan's Eire, Expain, Terrifier with Biaze Ya Dead Homie, Potluck with Rower Trip Code Orange Kids with In Solitude, Tribulation SIMON KING H TYPHOON j ANATHEMA THE SADIES with Radiation City, The Nautical Mites I withAlcest,Mammifer U wilt! guests 3 VAUENTTHORR CANCER BATS ORANGE GOBLIN OKKERVIL RIVER with Black Wizard, Lord Dying, with Bat Sabbath with Holy Grail, Lazer/Wulf, 88 Mite Trip with Special Guest Matthew E. White Ramming Speed THE LEGENDARY PINK DOTS ArawniiH KING KHAN &THE SHRINES RAE SPOON il YEAR 33 TOUR, with Magneticring witt White Knights Finish Last Slush with Hell Shovel i AN EVENIN6 WITH ANOIE BS1 N9NJASPY EP/0RAFH1C THE HI SEES E33 BC/DC&HAMWAILIN' MIN0USAND1ENB0HM •* NOVEL RELEASE PARTY!!! with the Blind Shake and OBNIlls Ell HALLOWEEN 2013 THESONiCS WE HUNT BUFFALO GOBLIN NERDFEST1ANIGHT0F fcafiff with My Goodness, The Vicious Cycles witt La Chinga, War Baby, If We Are V.Vecker Ensemble and Basketball Machines EH FANTASY Additional show listings, ticket info, band bios, videos and more are online at: WWW.