Adoptive Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iacs2017 Conferencebook.Pdf

Contents Welcome Message •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Conference Program •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Conference Venues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 Keynote Speech ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Plenary Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Special Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Parallel Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 Travel Information •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 228 List of participants ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 232 Welcome Message Welcome Message Dear IACS 2017 Conference Participants, I’m delighted to welcome you to three exciting days of conferencing in Seoul. The IACS Conference returns to South Korea after successful editions in Surabaya, Singapore, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangalore, Tokyo and Taipei. The IACS So- ciety, which initiates the conferences, is proud to partner with Sunkonghoe University, which also hosts the IACS Con- sortium of Institutions, to organise “Worlding: Asia after/beyond Globalization”, between July 28 and July 30, 2017. Our colleagues at Sunkunghoe have done a brilliant job of putting this event together, and you’ll see evidence of their painstaking attention to detail in all the arrangements -

FA-06 and FA-08 Sound List

Contents Studio Sets . 3 Preset/User Tones . 4 SuperNATURAL Acoustic Tone . 4 SuperNATURAL Synth Tone . 5 SuperNATURAL Drum Kit . .15 PCM Synth Tone . .15 PCM Drum Kit . .23 GM2 Tone (PCM Synth Tone) . .24 GM2 Drum Kit (PCM Drum Kit) . .26 Drum Kit Key Assign List . .27 Waveforms . .40 Super NATURAL Synth PCM Waveform . .40 PCM Synth Waveform . .42 Copyright © 2014 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION . © 2014 ローランド株式会社 本書の一部、もしくは全部を無断で複写・転載することを禁じます。 2 Studio Sets (Preset) No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 56 Dear My Friends 85 64 56 No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 57 Nice Brass Sect 85 64 57 1 FA Preview 85 64 1 58 SynStr /SoloLead 85 64 58 2 Jazz Duo 85 64 2 59 DistBs /TranceChd 85 64 59 3 C .Bass/73Tine 85 64 3 60 SN FingBs/Ac .Gtr 85 64 60 4 F .Bass/P .Reed 85 64 4 61 The Begin of A 85 64 61 5 Piano + Strings 85 64 5 62 Emotionally Pad 85 64 62 6 Dynamic Str 85 64 6 63 Seq:Templete 85 64 63 7 Phase Time 85 64 7 64 GM2 Templete 85 64 64 8 Slow Spinner 85 64 8 9 Golden Layer+Pno 85 64 9 10 Try Oct Piano 85 64 10 (User) 11 BIG Stack Lead 85 64 11 12 In Trance 85 64 12 No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 13 TB Clone 85 64 13 1–128 INIT STUDIO 85 0 1–128 129– 14 Club Stack 85 64 14 INIT STUDIO 85 1 1–128 256 15 Master Control 85 64 15 257– INIT STUDIO 85 2 1–128 16 XYZ Files 85 64 16 384 17 Fairies 85 64 17 385– INIT STUDIO 85 3 1–128 18 Pacer 85 64 18 512 19 Voyager 85 64 19 * When shipped from the factory, all USER locations were set to INIT STUDIO . -

Chapter 2. Analysis of Korean TV Dramas

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer Master’s Thesis of International Studies The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China 중한 드라마의 제작 과 방송 비교 August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University Area Studies Sheng Tingyin The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China Professor Jeong Jong-Ho Submitting a master’s thesis of International Studies August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University International Area Studies Sheng Tingyin Confirming the master’s thesis written by Sheng Tingyin August 2019 Chair 박 태 균 (Seal) Vice Chair 한 영 혜 (Seal) Examiner 정 종 호 (Seal) Abstract Korean TV dramas, as important parts of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), are famous all over the world. China produces most TV dramas in the world. Both countries’ TV drama industries have their own advantages. In order to provide meaningful recommendations for drama production companies and TV stations, this paper analyzes, determines, and compares the characteristics of Korean and Chinese TV drama production and broadcasting. -

Sir John Dering, a Romantic Comedy

Presented to the library of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO by THE ESTATE OF THE L^TL MARY SINCLAIR SIR JOHN DERING BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Broad Highwav The Amateur Gentleman The Money Moon The Hon. Mr. Tawnish The Chronicles of the Imp Beltane the Smith The Definite Object The Geste of Duke Jocelyn Our Admirable Betty Black Bartlemy's Treasure Martin Conisby's Vengeance Peregrine's Progress Sampson Low, Marston & Co., Ltd. SIR JOHN BERING A ROMANTIC COMEDY EY JEFFERY FARNOL AUTHOR OF "THE BROAD HIGHWAY" ETC. LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO. LTD. VV BR s^* AND SONS PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY PURNELL PAULTON, SOMERSET, ENGLAND TO MY FRIEND OF YEARS AND RIGHT TRUSTY COMRADE HERBERT LONDON POPE I DEDICATE THIS BOOK AS A SMALL TRIBUTE TO HIS PATIENCE, FAITHFULNESS, AND UN- FALTERING LOYALTY : WITH THE EARNEST HOPE THAT TIME MAY BUT KNIT US EVER MORE CLOSE JEFFERY FARNOL Sussex CONTENTS PAGE Prologue ...... I CHAP. I. Which introduces the Dog with a Bad Name II. Which describes a Fortuitous but Fateful Meeting ..... 20 III. Telleth of Mrs. Rose, the Guileful Innocent 29 IV. Sheweth the Wicked Dering in a New Role 34 V. The Allure of Simplicity : Moonlight and an Elopement ..... 39 VI. Of Souls, Solitude and a Dusty Road . 46 VII. Which introduces My Lord Sayle and the Clash of Steel .... 54 VIII. Of a Post-chaise, Iniquity and a Grandmother 65 IX. Describes the Adventures of the True Believer ...... 71 X. Further concerning the Same 79 XI. Of an Altruistic Scot .... 85 XII. Describeth the Duplicity of Innocence . -

SPECIAL ISSUE F Newsmagazine02

SPECIAL ISSUE F Newsmagazine02 Earrings by Teddie Bernard &z. (zeinab ajasa) &z. (zeinab INCONSISTENT: Man-Made Love by Wayne Degen honeymilk: page two & three by by & three two page honeymilk: Love is: A Wonderful Feeling “Love is when someone or something makes your heart skip a What is little.” Love? by Mimi Ozormoor “Love is a freedom in a sense. When you love yourself or someone else, it’s relieving.” F Newsmagazine03 Love & Other Disgusting Dating App Openers by Monica Gong It’s the beginning of a time like no other in Chicago: The 5. Public Sex: Part 2: The unfortunate chlamydia incident … lakefront is heating up, vaccines are rolling out, and we’re I had to read it, and now so do you! Note to self: Avoid Aisle 7 gearing up for a hedonistic summer. Unfortunately, dating at every Walgreens within a 50-mile radius. apps’ swipe-and-scroll methodology allow for a cesspool of less-than-desirable messages. Here are some of the crudest and cringiest interactions from the virtual dating world, sub- mitted by you, the members of the SAIC community. 1. The Male Gazer: An unforgettable opener continues the ugly tradition of obscene sexualization. A friendly reminder to never forget the all-powerful block button. 2. Public Sex: Part 1: The person who was strangely enthusi- astic about public sex during a worldwide pandemic. Social 6. A Persistent Horniness: The person who wasted neither distancing: Many of us are in need of a remedial lesson. time nor words. We should all aspire to be as efficient as them. -

1 Е.А. Голдобина О.Н. Корнева Т.К. Решетникова Students' Book

Е.А. ГОЛДОБИНА О.Н. КОРНЕВА Т.К. РЕШЕТНИКОВА STUDENTS’ BOOK ИЖЕВСК 2010 1 Предисловие Академическая мобильность- это неотъемлемая часть современного университетского образования. Её успешность обуславливается необходимым уровнем языковой и экстралингвистической подготовки. Для приобщения большего количества студентов к этой деятельности, авторами учебника был разработан специальный курс английского языка, цель которого – подготовить российских студентов к учебе в зарубежных вузах. При составлении учебника авторы использовали опыт, полученный ими в рамках нескольких международных проектов ТЕМПУС. Курс рассчитан на 110 аудиторных часов и является альтернативой традиционному курсу английского языка “General English” для студентов первого курса. В учебный комплекс входят: «Книга для студентов» и «Грамматический справочник для студентов». «Книга для студентов» состоит из двух разделов: «Selection of students for academic mobility at home university» и «Studying abroad» и тематически отражает основные стадии, через которые проходит студент, решивший принять участие в академической мобильности, а именно: подготовка и оформление документов (CV a cover letter, a letter of motivation), собеседование, прибытие в партнёрский университет, учёба, знакомство со страной и её культурой. Содержание учебника составлено с учетом трудностей, с которыми столкнулись российские студенты, участвовавшие в мобильности. Для того, чтобы нивелировать эти трудности, авторы данного учебного комплекса создали систему языковой подготовки к учебе в партнерских вузах: • При обучении за рубежом российские студенты сталкиваются с таким видом учебной деятельности как презентация. В «Книге студента» очень подробно, поэтапно объяснено что такое презентация, как подготовиться к презентации, как правильно составить текст выступления и какие языковые средства использовать, чтобы успешно представить его аудитории. Наши рекомендации и тренировочные упражнения позволяют студентам, начиная с простых тем “About myself” переходить к более сложным “Studying abroad”(в рамках первого курса). -

A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students' Academic Adaptation at The

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain Supervisors: Dr. Ibis M. Alvarez Dr. Crista Weise Candidate: Lin Cai Submitted for the Annual Report of the Doctoral Project Faculty of Education Psychology Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra September 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain . ii A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain Supervisors: Dr. Ibis M. Alvarez Valdivia Dr. Crista Weise Candidate: Lin Cai Faculty of Education Psychology Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra September, 2016 iii A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain iv A Study on Ph.D. Chinese Students’ Academic Adaptation at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express the most honest gratefulness to Dr. Ibis M. -

Fce First Certificate in English

CAMBRIDGE EXAMINATIONS, CERTIFICATES & DIPLOMAS FCE FIRST CERTIFICATE IN ENGLISH PAPER 2 SAMPLE PAPERS English as a Foreign Language PAPER 2 WRITING SAMPLE PAPER Part 1 You must answer this question. 1 You are studying in Cambridge at present and two friends from your country are coming to visit you next month. During their visit they would especially like to spend a few days in Edinburgh and you are planning to go with them. A travel agency has given you the following information. Read it carefully. Then write a letter to your friends, giving them some information about the three different ways of travelling to Edinburgh. Suggest which you think is the best way and explain why. TRAIN Cambridge dep. Edinburgh arr. 07.00 12.15 07.56 13.38 09.00 14.12 Return fare: £90 (Friday and Saturday) • Edinburgh £75 (all other days) 30% off with a young person’s rail card. • Cambridge • London COACH Cambridge to Edinburgh - 540 km Cambridge dep. Edinburgh arr. 11.00 22.05 CAR 18.08 06.35 22.30 12.25 Car hire: £40 a day plus petrol and Return fare: £60 (Friday and Saturday) £45 (all other days) 30% off with a young person’s coach Write a letter of between 120 and 180 words in an appropriate style on the opposite page. Do not write any addresses. Page 2 Part 2 Write an answer to one of the Questions 2 – 5 in this part. Write your answer in 120 – 180 words in an appropriate style on the opposite page, putting the question number in the box. -

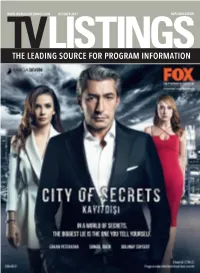

THE LEADING SOURCE for PROGRAM INFORMATION MEA 1017__Layout 1 9/22/17 11:33 AM Page 1 *LIST 1017-ADDITIONAL LIS 1006 LISTINGS 10/2/17 12:42 PM Page 3

*LIST_1017_COVER_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/28/17 11:09 AM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM OCTOBER 2017 MIPCOM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION MEA_1017__Layout 1 9/22/17 11:33 AM Page 1 *LIST_1017-ADDITIONAL_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 10/2/17 12:42 PM Page 3 IN THISISSUE TV LISTINGS 3 Monica Chef (Live-action drama/comedy, 3 18 4K MEDIA 40x22 min.) Monica has all the ingredients to 4K Media KABO International O (1-212) 590-2100 make her dream come true—she just needs to 9 Story Media Group Kanal D International control her musical daydreams and focus on 4 Keshet International Stand: R7.B12 becoming the chef she knows she can be. Kew Media Group 41 Entertainment Contact: Kristen Gray, SVP, operations & busi- Grace Beside Me (Live-action drama/comedy, Lacey Entertainment A+E Networks ness & legal affairs; Jennifer Coleman, VP, lic. & 13x26 min.) Fuzzy Mac’s life is turned upside The LEGO Group ABS-CBN Corporation mktg.; Jonitha Keymoore, pgm. sales dir. down when she discovers she can communicate Alfred Haber Distribution 19 with spirits. The series takes audiences on an all3media international Lionsgate Entertainment emotional roller-coaster ride as Fuzzy learns to American Cinema International Looking Glass International accept her “grace”-filled gift. 6 MarVista Entertainment The Samuel Project (Live-action drama, 1x90 Armoza Formats Mediaset Distribution min.) In search of a unique and engaging idea Artist View Entertainment Mediatoon Distribution for his high-school animation contest, teen illus- Atlantyca Entertainment 20 trator Eli Bergman unravels an incredible hid- ATRESMEDIA Televisión Mercis den story of perseverance and survival from his ATV Turkey Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios aging grandfather Samuel. -

Labor of Love: a Fred Smith Story

Untitled-3 1 2/18/2021 1:45:05 PM Labor of Love A Fred Smith Story Edited by Kent Lassman, Amanda France, and Ivan Osorio Competitive Enterprise Institute 2021 Labor of Love: A Fred Smith Story CONTENTS Introduction . .3 The Morality and Virtues of Capitalism and the Firm: Defending Capitalism in Theory and Practice . .9 Are Corporations Suicidal? . .45 The Value of Communicating to Joe and Joan “Citizen” . .48 Countering the Assault on Capitalism . .58 The Progressive Era’s Derailment of Classical Liberal Evolution . .70 Sustainable Development—A Free-Market Perspective . .82 Autonomy: The Liberating Benefits of a Safer, Cleaner, and More Mobile Society . .100 Cowboys Versus Cattle Thieves . .116 Why Not Abolish Antitrust? . .131 Supplemental Remarks to the House Banking Committee on the Future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, June 21, 2000 . .147 Charles Dickens’s Ebenezer Scrooge was the Ultimate Job Creator . .155 2 Labor of Love: A Fred Smith Story INTRODUCTION Everyone has a Fred Smith story. Often there is a telling detail coupled to an adjective that is both complimentary and ambiguous enough to draw the listener in for more. Charismatic. Brilliant. Peripatetic. Fun. Entrepreneurial. Charming. Generous. Willful. There are the stories about searches for ice cream sandwiches and Oreo cookies. Travel to foreign capitals. Mentoring. Partnerships with unexpected allies. And, of course, the time he hung up the phone on a cabinet official. He has been variably called maddening, crazy, unrealistic, idealistic. He believes in institutions and an unbounded capacity for mankind to improve, but not to perfect, life and our relationships. Above all, he is a friend, even if you haven’t met him yet. -

5Th Annual Redbud Health Walk a Success

Serving Rockcastle County Since 1887 Mount Vernon, Kentucky 40456 - (606) 256-2244 Volume 125 • Number 18 .50 per copy Thursday, April 7, 2011 New Post Office open for business in Renfro Valley By: Sara Coguer modate customers needs. The new Community The post office also of- Post Office is now open fers Express Mail ser- at the Kentucky Music vices, and their hours of Hall of Fame in Renfro business are Monday Valley. through Saturday, 10 a.m. The community post to 6 p.m. and Sunday 9 office is a full service a.m. to 3 p.m. These are post office offering post extended hours above office boxes, money or- and beyond normal post ders, stamps and flat-rate (Cont. to A9) priority boxes to accom- Several dignitaries and community members were on hand last Wednesday for the grand opening of Ham recovering the Community Post Office at the Renfro Valley Kentucky Music Hall of Fam and Museum. The CPO is now open to the public seven days a week. Participating in the ribbon cutting ceremonies were, from left” Denise Ralston, USPS, Danielle Smoot, Field Rep for U.S. Congressman Hal Rogers, at Cardinal Hill Chris Anderson, Postmaster at Mt. Vernon Post Office, Roy Martin, Chairman of the Hall of Fame, By: Sara Coguer Dwaine Harris, Tour SEKY and President of the Rockcastle Chamber of Commerce, Robert Lawson, Ham was airlifted to After being hit by a Director of the Hall of Fame and Museum, Randi Cross, USPS, Kim Owens, Hall of Fame Board the UK Medical Center line drive while pitching member, Norma Mullins, retired Postmistress of the Renfro Valley Post Office, Margaret Zentz, after becoming unrespon- in a softball game Mon- RCIDA Director Holly Hopkins, Gary Mink, and Arielle Reese, Chamber member. -

This Week in the Garden. the Poultry Yard

▪ • TEO: TEESDALE MERCURY-WEDNESDAY, oaromg 24, 1923. NOTES ON NEWS. " Is 1w? ii cried the wrathful voice of the r-1 father. "I'll tease 'im soon in a way 'e 'e won't like.. Now, Jim. my lad, leave off, or ma,e &emit that .a seterne js ! aat. 'thee al get no dinner. An' sv'en I Res yer .don't get it yer don't, so mind that. We've 1 a tUiVr 16^ 'come mit ere to enjoy ateselves, and not. to Zjt..117,4" over am bat:tine of the mo,,,„, MILL.GIRL OR .HEIRESS? ;be moithered vri' a lot o' kids." THIS WEEK IN THE GARDEN. ignees..,,,,,t}ahhaa trout t he old King's Peig By MRS. A. J. PHILLIPS, 1 Jim. seeing the firmness of hie father's wee, the Initiate iface, did leave off, and peace reigned once One nearer God's heart in a garden seotle , 11.4e0. The Melo is Author of "Swifter than a Weaver's Shuttle," "The Grindstone," eta. 1 more. Than anyTArhere else 4e73 earth. 'Kettle's mother," cried John 11,".1L legatee _curiam &Flit-11114'e haat' attiiie 'Enery joyfully. ■ he even to g. segue:. eseeschoily i , ,••• "There's a boy for Feta" chuckled Lie -•-•00"FT"' -' 11 tee mem:. cespeeettitiey 11%.1. Gt. mother. "Never geed the like of 'int afore. • "W''1/41 •4 aratite, Ask 'im to do a thing mid it's done at once. • •:41I"V:d tee Micemer sandy soil and place in a frost-proof frame. t • . Good lad! I'll make the tea, and every- ha aria in future hula the ineeei CHAPTER XVII (Continued).