The Many Faces of Turku - an Essayistic Study of Urban Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finnish Archipelago Incoming Product Manual 2020

FINNISH ARCHIPELAGO & WEST COAST Finnish Archipelago is a unique destination with more than 40 000 islands. The sea, forests, rocks, all combined together with silent island corners is all you need on your holiday. Local history and culture of the area shows you traditions and way of life in this corner of Finland. Local food is a must experience while you are going for island hopping or visiting one of many old wooden towns at the coast. If you love the sea and the nature, Finnish Archipelago and west coast offers refreshingly breezy experience. National parks (4) and Unesco sites (2) make the experience even more special with unique features. Good quality services and unique attractions with diverse and fascinating surroundings welcome visitors from all over. Now you have a chance to enjoy all this at the same holiday when the distances are just suitable between each destination. Our area covers Parainen (all the archipelago islands), Naantali, Turku, Uusikaupunki, Rauma, Pori, Åland islands and many other destinations at the archipelago, coast and inland. GENERAL INFO / DETAILS OF TOURS Bookings: 2-4 weeks prior to arrival. For bigger groups and for more information, please contact Visit Naantali or Visit Turku. We reserve the rights to all changes. Photo: Lennokkaat Photo: OUTDOORS CULTURE LOCAL LIFE WELLBEING TOURS CONTENT OF FINNISH ARCHIPELAGO MANUAL Page OUTDOORS 3 Hidden gems of the Archipelago Sea – An amazing Archipelago National Park Sea kayaking adventure 4 Archipelago Trail – Self-guided bike tour at unique surroundings 5 Hiking on Savojärvi Trail in Kurjenrahka National Park 6 Discover Åland’s Fishing Paradise with a local sport fishing expert 7 St. -

Turku's Archipelago with 20,000 Islands

Turku Tourist Guide The four “Must See and Do’s” when visiting Turku Moomin Valley Turku Castle The Cathedral Väski Adventure Island Municipality Facts 01 Population 175 286 Area 306,4 km² Regional Center Turku More Information 02 Internet www.turku.fi www.turkutouring.fi Turku wishes visitors a warm welcome. Photo: Åbo stads Turistinformation / Turku Touring Newspapers Åbo underrättelser www.abounderrattelser.fi/au/idag.php Turku’s Archipelago Turun Sanomat www.turunsanomat.fi with 20,000 Islands Finland’s oldest city. It’s easy to tour the archipelago. Tourist Bureaus Turku was founded along the Aura River in You can easily reach any of the 20,000 islands 1229 and the Finnish name Turku means and islets located in the Turku archipelago by Turku Touring “market place.” The city is called , “The Cradle ferry or boat (large or small). You can also Auragatan 4, Turku to Finnish Culture” and today, despite its long come close to the sea by going along the +358 2 262 74 44 history, a very modern city that offers art, Archipelago Beltway, which stretches over [email protected] music, Finnish design and much more. 200 km of bridges and islands. Here you can www.turkutouring.fi stay overnight in a small friendly hotel or B & There are direct connections with SAS / Blue B. The archipelago, with its clean nature and 1 from Stockholm or you can choose any of calm pace is relaxation for the soul! the various ferry operators that have several Notes departures daily to the city. Southwest Finland is for everyone 03 - large and small! Turku is known for its beautiful and lively The southwest area of Finland is a historic Emergency 112 squares, many cozy cafés and high-class but modern area which lies directly by the Police 07187402 61 restaurants. -

A Voluntary Local Review 2020 Turku

A Voluntary Local Review 2020 The implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the City of Turku Opening statement by the Mayor Cities are facing major challenges – climate change, digitalisation and the ageing and increasingly diverse population greatly impact on cities’ field of operation and require cities to be able to adapt to constant change. Adaptation and adjustment to conventional ways of doing things is also needed in order to reach sustainability on a global level. Cities and city networks have an ever-growing role to play as global influencers and local advocates in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Succeeding in accelerating sustainable development requires strong commitment and dedication from the city’s decision-makers and the whole city organization. Turku has a long tradition in promoting sustainable development and we want to make sure Turku is a good place to live in the future as well. Turku also wants to take responsibility and set an example in solving global sustainability challenges. That is why I consider it very important that Turku is among the first cities to participate in reporting city-level progress of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. With this first VLR report, I am very proud to present the systematic work being done in Turku for sustainable development. I hope that the cities’ growing role in implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development becomes more visible to citizens, business life, organisations, other cities, government and other interest groups. Together we have a chance to steer the course of development in a more sustainable direction. A Voluntary Local Review 2020, The implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the City of Turku Minna Arve Authors: City of Turku. -

Turun Keskiaikaisten Kylätonttien Kasvillisuus

Turun keskiaikaisten kylätonttien kasvillisuus Silja Aalto Pro gradu-tutkielma Arkeologia Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Humanistinen tiedekunta Turun yliopisto Elokuu 2020 Turun yliopiston laatujärjestelmän mukaisesti tämän julkaisun alkuperäisyys on tarkastettu Turnitin OriginalityCheck -järjestelmällä. TURUN YLIOPISTO Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos / Humanistinen tiedekunta SILJA AALTO: Turun keskiaikaisten kylätonttien kasvillisuus Pro gradu –tutkielma, 92 sivua, 21 liitesivua Arkeologia Elokuu 2020 Tässä tutkimuksessa selvitetään, minkälaista kasvillisuutta Turun alueen keskiaikaisilla kylätonteilla nykyään esiintyy ja poikkeaako eri ikäisten ja eri aikoina autioituneiden kylätonttien kasvillisuus toisistaan. Mikäli jotkin kasvilajit esiintyvät vanhoilla rautakaudelta periytyvillä asuinpaikoilla selvästi useammin kuin vasta keskiajalla perustetuissa kylissä, ne voisivat indikoida asutuksen vanhaa ikää. Samalla tarkastellaan, painottuuko tiettyjen kasvilajien levinneisyys Turussa keskiaikaisen kyläasutuksen läheisyyteen. Kasvillisuuden osalta aineisto koostuu Turun paikallisista luontoselvityksistä, Suomen lajitietokeskuksen kokoamista havainnoista ja Turun kasvit -hankkeen havaintopisteistä. Kyläaineisto pohjautuu pääasiassa Turun museokeskuksen inventointeihin vuosilta 2014 ja 2015. Ennen tutkimusta kyläkohtaista kasvillisuusaineistoa täydennettiin kenttätöillä. Analyysiin valittiin 11 autioitunutta kylätonttia: Haavisto, Harittu, Iisala, Ispoinen, Kairinen, Kakkarainen, Kalliola, Koskennurmi, -

Pansio RAKENNUSHISTORIASELVITYS

Markus Manninen Pansio RAKENNUSHISTORIASELVITYS MANARK 2020 © MARKUS MANNINEN JA ARKKITEHTITOIMISTO MANARK OY 2020 Ulkoasu ja taitto: Markus Manninen Valokuvat ja kartat, ellei toisin mainita: Arkkitehtitoimisto Manark Oy Kustantaja: Senaatti-kiinteistöt, Helsinki 2020 Painopaikka: Grano Oy, Jyväskylä ISBN 978-952-368-047-0 (painettu) ISBN 978-952-368-048-7 (PDF) 2 Sisällys 5 JOHDANTO 9 PANSION KYLÄ 101 LAIVASTOASEMA JA TELAKKA 9 Isotalo ja Vähätalo 1800–1899 101 Sodan ajan olosuhteissa 1945–1946 16 Huviloita ja satama-aikeita 1900–1923 106 Valmetin telakaksi 1946–1959 19 Merivoimien kaavailuja 1924–1937 114 Laivastoaseman toipumiskausi 1946–1959 23 Rakennukset vuoteen 1937 asti 122 Telakasta tehtaaksi 1960–1979 124 Uudistuksia laivaston vanavedessä 1960–1979 33 PÄÄTUKIKOHTA 134 Myöhemmät vaiheet 1980–2019 33 Pansion haltuunotto 1937–1939 36 Laivastoaseman perustaminen 1939 138 LÄHTEET JA LIITTEET 40 Suurtyön aloitus 1940 45 Uuteen sotaan 1941 47 Telakka ja työpajat 1942 54 Laaja työmaa 1943 59 Parakkeja ja viimeistelyä 1944 Kansi: Pansion esikunta- eli hallintorakennus n:o 76 vuonna 1968. SA-kuva 63 Rakennukset 1939–1944 Takakansi: Entisen tykkipajan n:o 58 pohjoisjulkisivu. Etusivu: Italialta ostettuja MAS-moottoritorpedoveneitä Pansion venevajassa n:o 72 keväällä 1944. SA-kuva Vas.: Pansion suunnittelu- ja rakennustöiden päällikkö, kommo- dori Eino Huttunen värittää Turun Laivastoaseman sijaintia ku- vaavaa karttaa toukokuussa 1944. Taustalla kohokuva laivasto- aseman alueesta. SA-kuva Yllä: Arkkitehti Risto-Veikko Luukkosen sisäperspektiivikuva to- teuttamattomasta Pansion upseerikerhosta vuodelta 1942. AM 3 PANSIO Rakennukset 1937 asti Rakennukset 1939—1944 Rakennukset 1945—1959 Rakennukset 1960—1979 Rakennukset 1980—2019 Riilahdentie KASARMIALUE KOIVULUOTO VALKAMALAHTI Laivastontie TYÖPAJA-ALUE TELAKKA-ALUE Taustailmakuva 2018 © Turun kaupungin Kaupunkiympäristötoimiala 4 Johdanto ASUNTOALUE Turussa sijaitseva Pansio on ainutlaatuinen, sotien aikana 1939–1944 raken- nettu laivastoasema. -

Contributions to the Macromycetes in the Oak Zone of Finland

Contributions to the macromycetes In the oak zone of Finland P a a v o K a l l i o and E s t e r i K a n k a i n e n Department of Botany, University of Turku Publications from the Department of Botany, University of Turku, N:o 114 The characteristics of the fungus flora the collecting operations and some of the of the oak zone of Finland have to some localities mentioned in the previous list extent been described in the papers of have been collected again. KARSTEN (1859), THESLEFF (1919), EKLUND The nomenclature follows that of SINGER (1943, 1944), and KALLIO (1963). The north (1962; Agaricales) and MosER (1963; Asco ern limit of the oak zone is one of the clear mycetes). All the specimens mentioned are est mycofloristic boundaries in northern preserved in TUR (Herbarium of the Uni Europe and some species - e.g. many bo versity of Turku).Abbreviations of persons: letes (KALLIO 1963) - are particularly good (SH) Seppo Hietavuo, (EK) Esteri Kankai indicators for this zone. nen, (PK) Paavo Kallio, (AN) Antti Nyman, In the following list, new localities of (RS) Raili Suominen. Abbreviations of pro some »southern species» are attached as vinces: A = Ahvenanmaa, V = Varsinais addenda to the list of KALLio (1963). Some Suomi, U = Uusimaa, St = Satakunta, EH new points for study have been included in = Etela-Hame, EK = Etela-Karjala. LIST OF THE SPECIES Ascomycetes Vuorentaka23. 10. 66 (AN); K a r j a I o h j a Pii pola Heponiemi 12. 9. 65 and 25. -

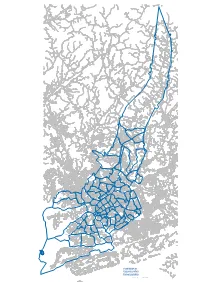

Turun Kaupunkiseudun Pyöräilyn Pääverkon Ja Laatukäytävien

Varsinais-Suomen liitto Egentliga Finlands förbund Regional Council of Southwest Finland TURUN KAUPUNKISEUDUN PYÖRÄILYN PÄÄVERKON JA LAATUKÄYTÄVIEN KEHITTÄMISSUUNNITELMA 2013 Turun kaupunkiseudun pyöräilyn pääverkon ja laatukäytävien kehittämissuunnitelma 2013 ISBN 978-952-5599-87-9 Varsinais-Suomen liitto PL 273 (Ratapihankatu 36) 20101 Turku (02) 2100 900 www.varsinais-suomi.fi Esipuhe Pyöräilyn edistäminen on yksi kestävän liikennepolitiikan kulmakivistä ja pyöräilyn suosion kasvattaminen on tavoitteena myös Turun seudun maankäytön ja liikennejärjestelmän kehittämisessä. Nyt käsillä olevan pyöräilyn pääverkon ja laatukäytävien kehittämissuunnitelman laatiminen on yksi Turun seudun rakenne‐ mallityön pohjalta kuntien ja valtion välille laaditun MAL‐sopimuksen toimenpiteistä. Samalla suunnitelma ja sen toteuttaminen ovat osa Turun kaupunkiseudun jatkuvaa liikennejärjestelmätyötä. Pyöräily on terveellinen ja ympäristöystävällinen, niin liikkujalle kuin yhteiskunnalle edullinen kulkutapa. Pyöräily ei aiheuta kasvihuonekaasupäästöjä, ilmansaasteita tai melua. Kun kaupunkirakenne on sellainen, että mahdollisimman moni matka on henkilöauton sijaan mahdollista tehdä kävellen ja pyöräillen, vie liik‐ kuminen vähemmän tilaa ja aiheuttaa vähemmän kustannuksia. Mitä suurempi osa matkoista tehdään pyö‐ rällä, sitä vähemmän on autoliikenteen ruuhkia ja sitä sujuvampaa liikenne on. Asukkaille itselleen liikunta ja sen terveyshyödyt ovat keskeinen motiivi arkimatkojen tekemiseen pyörällä. Samalla arkiliikunnan lisään‐ tyminen auttaa kuntia terveydenhoitokulujen -

ACCESS to GREEN Enhancing Urban Attractiveness in Urban Centers – the Case of Turku

Ana Maria Jones, Markku Wilenius & Suvi Niskanen ACCESS TO GREEN Enhancing Urban Attractiveness in Urban Centers – the Case of Turku FINLAND FUTURES RESEARCH CENTRE FFRC eBOOK 6/2018 2 Copyright © 2018 Writers & Finland Futures Research Centre, University of Turku Cover picture By Ana Jones Pictures in the report By Ana Jones if source not availaBle otherwise ISBN 978-952-249-517-4 (print) ISBN 978-952-249-516-7 (pdf) ISSN 1797-1322 3 PREFACE Nature is good for the city! Nature-based solutions is one of the key words in the debate on urban development today. Nature is expected – and proved – to serve many functions in our cities. Many challenges that would otherwise be hard to meet can best be solved by approaches where nature plays the key role. Climate Change is the greatest acute threat to humankind and the diverse forms of life on planet Earth. The City of Turku has responded strongly to this threat. We have already reduced a quarter of our emissions as compared to the level of 1990, and by 2029 Turku shall be a carbon-neutral area. Our Climate Plan 2029 was approved unanimously by City Council on the 11th of June this year. Nature plays an important role in both Climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate risks are significantly reduced by increasing the area of forests, greeneries and wetlands within the built city areas. At the same time, these solutions increase the daily wellbeing and health of the inhabitants. Furthermore, green corridors within the city serve as pleasant routes for walking and cycling as well as ecological corridors for animals, birds and insects. -

Turku Magazine 2020

Your Åboriginal guide, from Finland’s first city to the latest trends. 2020 In Turku PRESENTING THE BEST with INSTA-SPOTS P. 6 a camera EACH BITE OF THE MOOMIN PILGRIMAGE HUNGER IS AN PHENOMENON IN TURKU’S OPPORTUNITY They come from far and ARCHIPELAGO wide to the home of Tove St Olav’s Waterway The flavours of Jansson’s fairytale is heaven for sedate Turku’s restaurants p. 11 characters p. 24 explorers p.16 16–19 The easy explorer’s heaven Would you believe, a pilgrimage route runs across the sea and islands of Turku’s archpelago. 20 Rediscover your roots - in the trees! Luxury and nature in a tent at Ruissalo Spa. 21 TURKU INSPIRES Thousands of island stories 12 Showcasing 5 of the 40,000 islands in Turku’s archipelago. 22 From Turku to the water x 6 From the Aura to the Airisto waves and back. 23 From side to side across the sea Ride with the Vikings to Turku and Stockholm. 24–25 Moomins - the phenomenon Why is Tove Jansson so big in Japan? 26–27 Places to go with kids x 10 Childhood summer’s are never dull in Turku. 28–31 Underground Turku Dig deep into an alternative culture. 28 32–33 Galleries and museums x 12 Origins of the past and the original of today. 34 Walking & guided tours Let Visit Turku be your local guide. 35 Maps & information contents Answers to what and where. 18 2020 4 Editorial 5 TURKU INSPIRES Sounds that echo through the soul 16 Musical highlights from Turku and the archipelago. -

Matti Landvik

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS AII 341 Matti Landvik ISOLATED IN THE LAST REFUGIUM – The Identity, Ecology and Conservation of the Northernmost Occurrence of the Hermit Beetle Matti Landvik Painosalama Oy, Turku , Finland 2018 Turku Painosalama Oy, ISBN 978-951-29-7207-4 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7208-1 (PDF) TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS ISSN 0082-6979 (PRINT) | ISSN 2343-3183 (ONLINE) Sarja - ser. AII osa - tom. 341 | Biologica - Geographica - Geologica | Turku 2018 ISOLATED IN THE LAST REFUGIUM – The Identity, Ecology and Conservation of the Northernmost Occurrence of the Hermit Beetle Matti Landvik TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. A II osa - tom. 341 | Biologica - Geographica - Geologica | Turku 2018 University of Turku Faculty of Science and Engineering Biodiversity Unit Supervised by Professor Emeritus Pekka Niemelä Professor Tomas Roslin Biodiversity Unit Department of Ecology University of Turku Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Turku, Finland Uppsala, Sweden Department of Agricultural Sciences University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland Reviewed by Professor Paolo Audisio Associate Professor Andrzej Oleksa Department of Biology and Biotechnology Institute of Experimental Biology “C. Darwin” – Sapienza Rome University Kazimierz Wielki University Rome, Italy Bydgoszcz, Poland Opponent Professor Thomas Ranius Department of Ecology, Conservation Biology Unit Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala, Sweden Cover image © Matti Landvik The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-7207-4 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7208-1 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6979 (PRINT) ISSN 2343-3183 (ONLINE) Painosalama Oy - Turku, Finland 2018 “The four stages of acceptance: 1. -

Kaupunginosien Numerot Ja Ni

096 PAATTINEN 099 KOSKENNURMI 097 YLI-MAARIA 087 JÄKÄRLÄ 098 PAIMALA 086 MOISIO 095 SARAMÄKI 103 TASTO 089 LENTOKENTTÄ 088 URUSVUORI 085 RUNOSMÄKI 084 KÄRSÄMÄKI 093 METSÄMÄKI 102 HAAGA 077 MÄLIKKÄLÄ 083 KAERLA 092 ORIKETO 076 TERÄSRAUTELA 091 RÄNTÄMÄKI 073 VÄTTI 082 KASTU 094 HALINEN 075 RUOHONPÄÄ 101 KOROINEN 081 RAUNISTULA 072 KÄHÄRI 014 KOHMO 074 PITKÄMÄKI 013 KURALA 011 NUMMI 065 PERNO 071 POHJOLA 063 PAHANIEMI 064 ARTUKAINEN 006 VI 001 I 016 VARISSUO 007 VII 012 ITÄHARJU 062 ISO-HEIKKILÄ 002 II 021 KUPITTAA 008 VIII 066 PANSIO 003 III 015 PÄÄSKYVUORI 004 IV 022 KURJENMÄKI 009 IX 061 SATAMA 005 V 031 MÄNTYMÄKI 025 VAALA 023 VASARAMÄKI 026 LAUSTE 032 LUOLAVUORI 041 VÄHÄHEIKKILÄ 042 KORPPOLAISMÄKI 053 PIKISAARI 043 PUISTOMÄKI 024 HUHKOLA 044 PIHLAJANIEMI 052 LAUTTARANTA 033 PELTOLA 067 RUISSALO 034 ILPOINEN 037 SKANSSI 049 JÄNESSAARI 035 KOIVULA 046 UITTAMO 051 MOIKOINEN 154 SÄRKILAHTI 057 KUKOLA 045 ISPOINEN 036 HARITTU 153 TOIJAINEN 047 KATARIINA 056 ILLOINEN 059 KAISTARNIEMI 068 MAANPÄÄ 054 HAARLA 055 ORINIEMI 058 PAPINSAARI 048 FRISKALA 151 SATAVA 152 VEPSÄ Ympäristötoimiala Kaupunkisuunnittelu Kaavoitusyksikkö 12.9.2016, VN Mittakaava: 1:110000 001 I 001 I 002 II 002 II 003 III 003 III 004 IV 004 IV 005 V 005 V 006 VI 006 VI 007 VII 007 VII 008 VIII 008 VIII 009 IX 009 IX 064 ARTUKAINEN ARTUKAIS 011 NUMMI NUMMISBACKEN 048 FRISKALA FRISKALA 012 ITÄHARJU ÖSTERÅS 102 HAAGA HAGA 013 KURALA KURALA 054 HAARLA HARLAX 014 KOHMO KOHMO 094 HALINEN HALLIS 015 PÄÄSKYVUORI SVALBERGA 036 HARITTU HARITTU 016 VARISSUO KRÅKKÄRRET 024 HUHKOLA HUHKOLA -

Pansion Sataman Asemakaavan Ja Asemakaavanmuutoksen Selostus (58/2001)

Pansion sataman asemakaavan ja asemakaavanmuutoksen selostus (58/2001) Selostus koskee 5. päivänä lokakuuta 2004 päivättyä ja 23.11.2005 lausuntojen perusteella muutettua asemakaavakarttaa. 2 1 PERUS- JA TUNNISTETIEDOT Asemakaavanmuutos koskee: Turun kaupungin Kaupunginosa: 066 PANSIO PANSIO Korttelit: 4-14, 22 ja 29 4-14, 22 och 29 Korttelit ja tontit: 38.-3, 38.-7 ja 52.-8 38.-3, 38.-7 och 52.-8 Kadut: Ahtaajankatu Stuvaregatan Paakarlantie (osa) Bagarlavägen (del) Pansiontie (osa) Pansiovägen (del) Pernontie (osa) Pernovägen (del) Pohjoissalmenkatu Pohjoissalmigatan Siilinpolku Igelkottsbrinken Sukeltajankatu Dykarevägen Uusi Ruissalontie Nya Runsalavägen Valmetinkatu (osa) Valmetgatan (del) Öljykatu Oljegatan Virkistysalueet: Hiirenpuisto (osa) Musparken (del) Kisapuisto Lekparken Pansiontienpuisto Pansiovägparken nimettömiä puistoalueita parkområden utan namn Liikennealueet: Artukaistenlaituri Artukaiskajen Pansion liikennealue Pansio trafikområde Pansionraide Pansiospåret Pohjoissalmen liikennealue Pohjoissalmi trafikområde Öljysataman liikennealue Oljehamnens trafikområde nimetön rautatiealue järnvägsområde utan namn Vesialueet: Pohjoissalmi (osa) Norra sundet (del) Raisionjoki (osa) Reso å (del) nimetön vesialue vattenområde utan namn Kaupunginosa: 67 RUISSALO RUNSALA Katu: nimetön katualue gatuområde utan namn Vesialue: nimettömiä vesialueita vattenområden utan namn 3 Asemakaavalla ja asemakaavanmuutoksella muodostuva tilanne: Kaupunginosa: 066 PANSIO PANSIO Liikennealue: Pansion satama (osa) Pansiohamnen (del) Vesialue: Pohjoissalmi