This Volume Is Published Thanks to the Support of the Directorate General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincia Di Bergamo

COMUNE DI GANDINO Provincia di Bergamo Piano di Emergenza Comunale ALLEGATI OPERATIVI E GLOSSARIO 14_022 PEC DEFINITIVA - D 0 Giugno 2015 Prima emissione 1 - - 2 - - 3 - - Dott. Geol. SERGIO GHILARDI iscritto all' O.R.G. della Lombardia n° 258 Studio G.E.A. 24020 RANICA (Bergamo) Via La Patta, 30/d Telefono e Fax: 035.340112 E - Mail: [email protected] Dott. Ing. FRANCESCO GHILARDI iscritto Ord. Ing. Prov. BG n. 3057 Prat. 14_022 Comune di Gandino (Bergamo) SOMMARIO 1 MODULISTICA DI EMERGENZA ................................................................................................... 2 2 ELENCHI E RISORSE DEL TERRITORIO A SUPPORTO DEL PIANO ....................................... 3 2.1 Dati generali .......................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Elenco frazioni e località abitate principali ........................................................................ 4 2.3 Risorse Idriche ...................................................................................................................... 5 2.4 Distributori di carburante e impianti similari ..................................................................... 7 2.5 Personale sanitario residente / operante sul territorio o nei comuni limitrofi ............... 8 2.5.1 Medici e ambulatori .......................................................................................................... 8 2.5.2 Veterinari .......................................................................................................................... -

Ordinato Per Nominativo)

ELENCO DEL PERSONALE CON CONTRATTO A TEMPO DETERMINATO AMMESSO AD USUFRUIRE DEI PERMESSI DIRITTO ALLO STUDIO ANNO 2019 (ORDINATO PER NOMINATIVO) Tipologia del I.C./I.S. DI SERVIZIO corso SETT. INIZIO TERMINE COGNOME NOME ORDINE SCUOLA DATA NOMINA DATA NOMINA ORARIO CATT.7SERV. GIORNI DI SERVIZIO MESI RICONOSCIUTI ORE SPETTANTI Primaria ACQUAROLI CRISTIAN 12/09/2018 30/01/2019 24 141 5 LAUREA I.C. DI BREMBATE SOTTO 31 Sec.2° grado ACQUAVIVA FRANCESCO 05/11/2018 08/06/2019 12 216 7 24 CFU I.S. "G. NATTA" DI BERGAMO 29 Primaria AGAZZI ANDREA DIPL. ACC. I.C. DI BORGO DI TERZO 05/11/2018 31/03/2019 24 147 5 2° LIV 31 Primaria AIOLFI IRENE 05/11/2018 28/03/2019 24 144 5 LAUREA I.C. "I MILLE" DI BERGAMO 31 Sec.2° grado AMRANI HAMZA LAUREA I.S. "PALEOCAPA" DI BERGAMO 14/01/2019 15/04/2019 18 92 3 19 Sec.2° grado ANANIA CARMINE 15/10/2018 22/02/2019 18 131 4 LAUREA IPIA "C.PESENTI" DI BERGAMO 25 Primaria BARDELLA VERA LAUREA I.C. "FRATELLI D'ITALIA" DI 17/12/2018 26/02/2019 24 72 2 COSTA VOLPINO 13 Primaria BARONI FRANCESCA 07/01/2019 17/04/2019 24 101 3 LAUREA I.C. DI SAN GIOVANNI BIANCO 19 Sec.1° grado BIANCO FLAVIA 07/01/2019 01/03/2019 18 54 2 LAUREA I.C. DI CLUSONE 13 Primaria BONATI CHIARA 09/11/2018 22/03/2019 10 134 4 LAUREA I.C. DI PONTE SAN PIETRO 10 Primaria BRIONI LAURA 17/09/2018 30/01/2019 20 136 5 LAUREA I.C. -

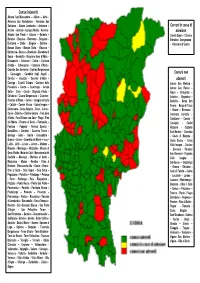

ALLEGATO 4: CARTOGRAFIA DI INQUADRAMENTO (Fonte: Sistema Informativo Territoriale – SITER - Della Provincia Di Bergamo)

ALLEGATO 4: CARTOGRAFIA DI INQUADRAMENTO (fonte: Sistema Informativo TERritoriale – SITER - della Provincia di Bergamo) VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO CERETE ROVETTA COSTA VOLPINO BOSSICO SOVERE GANDINO LOVERE 1:50.000 Confine comunale Industriale Raffreddamento Scarico di emergenza privato Scarico depurato pubblico Terminale pubblica fognatura bianche Scarico di emergenza (Staz. sol. / bypass) Sfioratore Sfioratore/scarico staz. sollevamento Reticolo idrografico Carta degli scarichi autorizzati in corpo d'acqua superficiale VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO CERETE ROVETTA COSTA VOLPINO BOSSICO SOVERE GANDINO LOVERE 1:50.000 Confine comunale Sorgenti / Fontanili Derivazioni superficiali Pozzi Potabile Potabile Potabile Antincendio Antincendio Antincendio Igienico Igienico Igienico Industriale Industriale Industriale Produzione Energia Produzione Energia Produzione Energia Piscicoltura Piscicoltura Piscicoltura Zootecnico Zootecnico Irriguo Zootecnico Irriguo Uso Domestico Irriguo Uso Domestico Altro uso Uso Domestico Altro uso Altro uso Carta delle piccole derivazioni di acqua VILMINORE DI SCALVE VALGOGLIO GROMO COLERE ´ OLTRESSENDA ALTA ARDESIO ANGOLO TERME CASTIONE DELLA PRESOLANA FINO DEL MONTE VILLA D`OGNA PARRE PIARIO ONORE CLUSONE ROGNO SONGAVAZZO -

Ambito Territoriale Valle Seriana

AMBITO TERRITORIALE VALLE SERIANA Comuni di Albino, Alzano L.do, Aviatico, Casnigo, Cazzano, Cene, Colzate, Fiorano al Serio, Gandino, Gazzaniga, Leffe, Nembro, Peia, Pradalunga, Ranica, Selvino, Vertova, Villa di Serio Comunità Montana Valle Seriana PIANO DI ZONA LEGGE 328/00 TRIENNIO 2018-2020 RELAZIONE DI RENDICONTAZIONE ATTIVITA’ SVOLTE ANNO 2019 Relazione a cura della SERVIZI SOCIOSANITARI VALSERIANA s.r.l. Viale Stazione 26/a Albino (BG) - CF e P.I 03228150169 – REA di Bg 360161 e-mail: [email protected], per info: www.ssvalseriana.org Presentazione in assemblea dei Soci: 01.07.2020 Relazione di rendicontazione attività svolte Anno 2019 2 Relazione di rendicontazione attività svolte Anno 2019 Egregi Sindaci, Il bilancio consuntivo per il 2019 ha segnato ancora una volta un risultato positivo sia in termini economici che di cura e attenzione al nostro territorio. L’evidenza di quanto detto la possiamo facilmente riscontrare nei documenti in allegato ed in particolare nella consueta relazione delle attività intraprese durante l’anno che hanno visto tutta la struttura societaria impegnata nel raggiungimento degli obiettivi indicati dalla Direzione. A tal riguardo il CDA ringrazia il Direttore dott. Marino Maffeis e tutto il personale, interno ed esterno, per l’intenso e proficuo lavoro svolto. Continua il lavoro di miglioramento della nostra società nel comparto normativo e di controllo della gestione attraverso l’assunzione di una risorsa a tempo pieno nell’area amministrativa ed in particolare si è conclusa la ricerca di un nuovo Direttore Generale considerata la quiescenza del dott. Marino Maffeis e la necessità di dotare la Società di una figura con un diverso profilo, più adeguato alle mutate condizioni di conduzione e di programmazione delle iniziative della Società. -

PDF Dei Turni

TURNI FARMACIE BERGAMO E PROVINCIA mercoledì 1 settembre 2021 Zona Località Ragione Sociale Indirizzo Da A Da A Alta Valle Seriana Rovetta Re Via Tosi 6 9:00 9:00 Bg citta Bergamo Borgo Palazzo Bialetti Via Borgo Palazzo 83 9:00 12:30 15:00 20:00 Cinque Vie dr. Rolla G.P. & C. Via G. B. Moroni 2 9:00 9:00 Hinterland Curno Invernizzi dr. Invernizzi G.& C Snc Via Bergamo 4 9:00 9:00 Stezzano S.Giovanni Srl Via Dante 1 9:00 0:00 Imagna Capizzone Valle Imagna Snc Corso Italia 17 9:00 9:00 Isola Almè Visini Del dr. Giovanni Visini & C. Snc Via Italia 2 9:00 9:00 Carvico Pellegrini dr. Reggiani Via Don Pedinelli 16 9:00 0:00 Romano Ghisalba Pizzetti Sas Via Provinciale 48/B 9:00 9:00 Seriate Grumello Chiuduno Farmacia S. Michele Srl Via C. Battisti 34 9:00 0:00 Gorle Pagliarini dr. Dario Via Mazzini 2 9:00 9:00 Treviglio Canonica d'Adda Peschiulli Sas Via Bergamo 1 9:00 20:00 Caravaggio Antonioli & C. Sas Via Matteotti 14 9:00 20:00 Treviglio Comunale N.3 Treviglio Az. Sp. Farm. Viale Piave 43 20:00 9:00 Valle Brembana Oltre il Colle Farmacia Viganò Di Passera dr.ssa Francesca Via Roma 272 9:00 9:00 San Pellegrino Terme Della Fonte Snc Viale Papa Giovanni 12 9:00 9:00 Valle Cavallina Alto e BassoBerzo San Sebino Fermo Scarpellini Via Europa Unita 14 9:00 9:00 Trescore Albarotto Srl Via Volta 26 9:00 9:00 Valle Seriana Leffe Pancheri Sas Via Mosconi 10 9:00 9:00 Pradalunga Strauch dr. -

Dott. Asperti Giorgio Curriculum Vitale

Dott. Asperti Giorgio Via XXV Aprile n. 9 24055 Cologno al Serio (BG) C.F. SPRGRG67R24C894F Iscrizione Albo Architetti – Pianificatori Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Bergamo Sezione A - n. 2165 Curriculum vitale Pag. 1 a 31 Dott. Asperti Giorgio Via XXV Aprile n. 9 24055 Cologno al Serio (BG) C.F. SPRGRG67R24C894F Iscrizione Albo Architetti – Pianificatori Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Bergamo Sezione A - n. 2165 SOMMARIO Informazioni personali .......................................................................................................... 3 Istruzione e formazione......................................................................................................... 3 Principali Aggiornamenti Professionali – Corsi di Formazione - ................................... 5 Esperienza lavorativa .......................................................................................................... 10 Principali Collaborazioni e Consulenze Tecniche e di Supporto al RUP saltuarie ed occasionali rispetto all’attività svolta al datore di lavoro principale ............................ 12 Capacità e competenze personali ...................................................................................... 14 Scheda A - REFERENZE RESPONSABILE UNICO DEL PROCEDIMENTO O SUPPORTO AL R.U.P. ........................................................................................................ 15 Scheda B - REFERENZE PIU’ SIGNIFICATIVE COMMISSARIO DI GARA METODO “ECONOMICAMENTE PIU’ VANTAGGIOSA” – APPALTI DI SERVIZI e/o FINANZA DI PROGETTO -

Il Paesaggio Tra Natura, Filosofia E Arte

PERCORSI FILOSOFICI Martinengo Con il patrocinio dei comuni di: Il Filandone IN ANTICHE DIMORE Per distinguerlo dagli opi- fici più piccoli, il Filandone viene costruito tra il 1873 e il 1876 dalla famiglia Dai- na. Nell’asta del 1934 la proprietà passa a Lucia Ca- lori in Allegreni. Nel 1956, a seguito dell’invenzione di nuovi sistemi automatici di filatura dei bozzoli, anche a Martinengo si installa una nuova filanda sperimentale, i cui macchinari sono inseriti in un nuovo capannone costruito attorno al 1950 attigui alla facciata prin- un ringraziamento particolare a: cipale nord. Successivamente l’intero complesso viene abbandonato, con cessione al Ministero del Tesoro, fino all’acquisizione finale da parte del Comune di Martinengo nel 1982. Nel 1976 il regista Ermanno Olmi vi girò alcune scene del film “L’albero degli zoccoli”.La fabbrica si presenta in stile neogotico lombardo, di cui riprende non solo lo stile, ma anche i materiali. Zanica Biblioteca di Martinengo stampato su carta 100% riciclata Villa Municipale Il Municipio di Zanica è si- tuato nell’ex Villa Spasciani, Cav. Claudio d’Isanto edificio risalente agli ini- agenzia di Martinengo via Allegreni 35 zi del ‘900 fatto edificare dall’omonima famiglia di origini milanesi. L’edificio, pur in un quadro di riferi- menti variegato, reca alcuni di San Pellegrino Terme caratteri ascrivibili al gusto liberty. L’ampio ambiente di ingresso è carat- terizzato da una doppia altezza ed è illuminato da un lucernario.La villa è circondata da un parco all’inglese, creato con la villa stessa, che ha sostanzialmente mantenuto il disegno originario, conservando anche il Visite guidate di Martinengo sistema di rogge - tuttora funzionante - pensate per l’irrigazione degli a cura della Pro loco di Martinengo ampi parterre a prato. -

Mappatura Soste a Pagamento Per Rifugi-1

ELENCO SOSTE A PAGAMENTO NEI PUNTI DI PARTENZA DI SENTIERI E ITINERARI ESCURSIONISTICI VALSERIANA E VAL DI SCALVE DURATA PERIODO DI SOSTA COMUNE PARCHEGGIO PUNTI DI ACQUISTO IMPORTO TIPOLOGIA ECCEZIONI E GRATUITÀ MASSIMA NOTE VALIDITÀ PLURIGIORNALIERA SOSTA ALBINO Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri ALZANO LOMBARDO Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri Esclusi i residenti e i proprietari di immobili nel territorio Area Laghetto di Valcanale e In caso di esaurimento posti servizio di bus navetta con di Ardesio, previa richiesta pass annuo presso uffici Polizia sentiero per Rifugio Alpe Corte (2 Massimo una partenza dal parcheggio "Gronde" a 1km dal Laghetto al locale o biblioteca (ogni famiglia può avere un permesso ARDESIO parcheggi, tot. 150 posti) + strada Parchimetro in loco 3€ per 24 ore Parchimetro Tutto l'anno Una settimana settimana al costo di costo di 5€ andata e ritorno nei seguenti periodi: dal per un solo automezzo, indicando la targa). Sono esclusi di accesso al sentiero (ulteriori 80 20€ 15.07.20 al 23.08.20 solo la domenica, dal 10.08.20 al anche i disabili, con esposizione sul mezzo di apposito posti) 16.08.20 tutti i giorni. contrassegno. AVIATICO Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri AZZONE Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri CASNIGO Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri CASTIONE DELLA Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri PRESOLANA CAZZANO S. ANDREA Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso ai sentieri CENE Nessuna sosta a pagamento per accesso -

Variante CDA 14.10.2020.Pdf

NUOVA PROPOSTA PDI 2020 - 2023 Consuntivo invetsimenti 2018 - 2019 Programma degli Interventi 2018 - 2023 Variante CDA dell'Ufficio d'Ambito 14.10.2020 Delibera N° 18 CONSUNTIVO 2018 TEMPISTICA COMUNI SEGMENTO AREA ID INTERVENTO DENOMINAZIONE INTERVENTO (RIVISTO COME DA PDI CONSUNTIVO 2019 Pianificato 2020 Pianificato 2021 Pianificato 2022 Pianificato 2023 CHIUSURA INTERESSATI IDRICO TRASMESSO AD ARERA) INTERVENTO Estensione acquedotto per collegamento con nuova fonte di INGEGNERIA Bianzano Acquedotto UNIA1AC020L01 0 0 0 0 0 200.304 2023 approvvigionamento INGEGNERIA Castelli Calepio Acquedotto UNIA1AC024L01 Potenziamento del rifornimento idrico dei Comuni della Val Calepio 0 0 0 0 0 350.000 2023 INGEGNERIA Ghisalba Acquedotto UNIA1AC053L01 Realizzazione nuovo pozzo 0 0 0 0 0 234.000 2023 Captazione Sorgente San Carlo (galleria) con realizzazione di stazione di INGEGNERIA Costa Volpino Acquedotto UNIA1AC164L01 pompaggio e connessione a rete di distrubuzione Acquedotto Intercomunale 0 0 0 0 0 150.000 2023 Alto Sebino INGEGNERIA Bottanuco Acquedotto UNIA1AC170L01 Realizzazione nuovo pozzo 0 0 100.000 200.000 0 0 2021 INGEGNERIA Clusone Acquedotto UNIA3AA032L01 Rifacimento rete adduzione da sorgente Nasolino a serbatoio Chiesa - 1° LOTTO 0 0 0 0 0 600.000 2023 INGEGNERIA Endine Gaiano Acquedotto UNIA3AA041L01 Spostamento Acquedotto dei Laghi in località Cantamesse 0 13.296 0 483.000 200.000 0 2022 INGEGNERIA Fonteno Acquedotto UNIA3AA046L01 Rifacimento rete di adduzione da sorgente Grioni a serbatoio Ponte - 1° LOTTO 0 0 0 0 0 350.000 2023 -

Trasf Docenti Sec I Gr 13-14.Pdf

********************************************************************************** * SI-13-SM-PDO2B * * * * SISTEMA INFORMATIVO MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE * * * * * * SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI PRIMO GRADO * * * * * * UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA LOMBARDIA * * * * * * UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE : BERGAMO * * * * * * ELENCO DEI TRASFERIMENTI E PASSAGGI DEL PERSONALE DOCENTE DI RUOLO * * * * * * ANNO SCOLASTICO 2013/2014 * * * * * * ATTENZIONE: PER EFFETTO DELLA LEGGE SULLA PRIVACY QUESTA STAMPA NON * * CONTIENE ALCUNI DATI PERSONALI E SENSIBILI CHE CONCORRONO ALLA * * COSTITUZIONE DELLA STESSA. AGLI STESSI DATI GLI INTERESSATI O I * * CONTROINTERESSATI POTRANNO EVENTUALMENTE ACCEDERE SECONDO LE MODALITA' * * PREVISTE DALLA LEGGE SULLA TRASPARENZA DEGLI ATTI AMMINISTRATIVI. * * * * * ********************************************************************************** POSTI DI SOSTEGNO PER MINORATI PSICO-FISICI ***** TRASFERIMENTI NELL'AMBITO DEL COMUNE 1. FORNAZAR GIUSEPPE . 10/11/71 (EE) TIT. SU POSTI DI SOSTEGNO (MIN. PSICO-FIS.) DA : BGMM818024 - S.M.S. ABBAZIA ( ALBINO ) A : BGMM818013 - S.M.S."G.SOLARI" ALBINO ( ALBINO ) PUNTI 69 ***** TRASFERIMENTI NELL'AMBITO DELLA PROVINCIA 1. ALBANESE EMANUELE . 10/10/79 (RC) TIT. SU POSTI DI SOSTEGNO (MIN. PSICO-FIS.) DA : BGMM83103G - S.M.S."F.LLI TERZI" PALOSCO ( PALOSCO ) A : BGMM863033 - S.M.S. SCANZOROSCIATE ( SCANZOROSCIATE ) PUNTI 50 2. AMERISE MARILENA . 1/ 7/78 (CS) TIT. SU POSTI DI SOSTEGNO (MIN. PSICO-FIS.) DA : BGMM000VQ6 - PROVINCIA DI BERGAMO A : BGMM842021 - S.M.S. BOLTIERE -

Comuni Aderenti: Comuni in Corso Di Adesione

Comuni aderenti: Albano Sant'Alessandro – Albino – Almè - Almenno San Bartolomeo - Almenno San Salvatore - Alzano Lombardo – Ambivere – Comuni in corso di Arcene – Ardesio - Arzago d'Adda – Averara - adesione: Azzano San Paolo – Azzone – Barbata – Cenate Sopra – Clusone Bariano – Barzana – Berbenno – Bergamo – Entratico - Songavazzo Bianzano – Blello - Bolgare – Boltiere - – Vilminore di Scalve Bonate Sopra - Bonate Sotto – Bossico – Bottanuco – Bracca – Brembate - Brembate di Sopra – Brembilla - Brignano Gera d'Adda – Brusaporto – Calcinate – Calcio – Caluisco d’Adda - Calvenzano - Canonica d'Adda - Capriate San Gervasio – Caprino Bergamasco – Caravaggio - Carobbio degli Angeli – Comuni non Carvico – Casazza - Casirate d'Adda – aderenti: Casnigo - Castelli Calepio - Castione della Adrara San Martino - Presolana – Castro – Cavernago - Cenate Adrara San Rocco – Sotto - Cene – Cerete - Chignolo d'Isola – Algua – Antegnate – Chiuduno - Cisano Bergamasco – Ciserano - Aviatico - Bagnatica – Cividate al Piano – Colere - Cologno al Serio Bedulita - Berzo San – Colzate - Comun Nuovo - Corna Imagna – Fermo – Borgo di Terzo Cortenuova - Costa Volpino – Covo – Curno – – Branzi – Brumano - Cusio – Dalmine – Endine Gaiano - Fara Gera Camerata Cornello – d'Adda - Fara Olivana con Sola – Filago - Fino Capizzone - Carona - del Monte - Fiorano al Serio – Fontanella – Cassiglio - Castel Fonteno – Foppolo - Foresto Sparso – Rozzone - Cazzano Gandellino – Gandino - Gaverina Terme – Sant'Andrea – Cornalba Gorlago – Gorle - Gorno – Grassobbio – - Costa di -

CALENDARI UFFICIALI Federazione Italiana

Federazione Italiana Pallavolo CALENDARI UFFICIALI Comitato Provinciale di BERGAMO Stagione 2008/09 II^ Divisione Femminile Girone A Pagina: 1 1 Giornata 565 ME 29/10/08 21.15 PALAGORLE GORLE PALLAVOLO GORLE A.S. MARTINENGO VOLLEY 566 ME 29/10/08 21.00 PALESTRA SCUOLE MEDIE "SAVOIA" BERGAMO FOPPAPEDRETTI HAPPY IDEA CAZZANO 567 ME 29/10/08 21.00 PALESTRA SCUOLE MEDIE "A.MORO" URGNANO G.S. IRIDE URGNANO RAVELPHONE GRUMELLO 568 ME 29/10/08 21.15 PALESTRA SCUOLE ELEM. NEMBRO VOLLEY NEMBRO SCANZO PALLAVOLO GAVARNO 569 ME 29/10/08 21.00 PALESTRA COMUNALE MORNICO AL SERIO POLISP.VOLLEY MORNICO U.S.O. ALZANESE 570 ME 29/10/08 21.00 PALESTRA SCUOLE MEDIE CIVIDATE AL PIANO CAPRONI ASSICURAZIONI A.D. CAROBBIO VOLLEY 571 ME 29/10/08 20.45 PALESTRA LOCALITA' TRELLO LOVERE PALL. VALLECAMONICA SEBINO ASD VOLLEY TRESCORE BALNEARIO 2 Giornata 572 ME 05/11/08 20.30 PALESTRA SCUOLE ELEMENTARI MARTINENGO A.S. MARTINENGO VOLLEY CAPRONI ASSICURAZIONI 573 ME 05/11/08 21.00 PALESTRA SCUOLA MEDIA LEFFE HAPPY IDEA CAZZANO PALL. VALLECAMONICA SEBINO 574 ME 05/11/08 21.00 PALESTRA SCUOLE MEDIE "SIGNORELLI GRUMELLO DEL MONTE RAVELPHONE GRUMELLO FOPPAPEDRETTI 575 ME 05/11/08 21.00 PALESTRA SC. ELEMENTARI NEMBRO PALLAVOLO GAVARNO PALLAVOLO GORLE 576 GI 06/11/08 21.15 PALAZZETTO DELLO SPORT ALZANO LOMBARDO U.S.O. ALZANESE VOLLEY NEMBRO SCANZO 577 ME 05/11/08 21.00 PALAZZETTO DELLO SPORT CAROBBIO DEGLI ANGELI A.D. CAROBBIO VOLLEY G.S. IRIDE URGNANO 578 ME 05/11/08 20.30 PALESTRA SC.