A Riot of Our Own: a Reflection on Agency Carol Tulloch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

English Beat: in Concert at the Royal Festival Hall DVD Reviewed on Audiovideorevolution.Com

English Beat: In Concert at the Royal Festival Hall DVD Reviewed on AudioVideoRevolution.com title: English Beat: In Concert at the Royal Festival Hall studio: Secret Films MPAA rating: Not Rated starring: English Beat DVD release 2005 year: film rating: Three Stars sound/picture: Three Stars reviewed by: Dan MacIntosh When you break it right down, there’s nothing particularly English about The English Beat. You may recall how the group was once lumped in with the whole ska movement back in the ‘80s, mainly because it was on the 2 Tone Records label, along with The Specials and The Selector. But if you listen closely, you hear very little actual ska (which is not exactly a British export in the first place) in the group’s songs. For instance, the only horn player in this outfit is the ancient Saxa, who would much rather play mellow jazz than skanking beats anyhow. Furthermore, the group’s repertoire contains a bounteous supply of reggae – both fast and slow – as well as other dance grooves. But no matter the style, all of these elements support this act’s punkish political attitude, which is possibly its lone true English attribute. This show, which was filmed at The Royal Festival Hall in London, England, features quite a few of the band’s original members. These players include the two front people, Ranking Roger and Dave Wakeling, as well as Saxa and drummer Everett Morton. And except for Saxa, of course, all of these musicians still look incredibly young. Better yet, they also sound great. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Catalogue 1949-1987

Penguin Specials 1949-1987 for his political activities and first became M.P. for West Fife in 1935. S156-S383 Penguin Specials. Before the war, when books could be produced quickly, we used to publish S156 1949 The case for Communism. volumes of topical interest as Penguin Specials. William Gallacher We are now able to resume this policy of Specially written for and first published in stimulating public interest in current problems Penguin Books February 1949 and controversies, and from time to time we pp. [vi], [7], 8-208. Inside front cover: About this shall issue books which, like this one, state the Book. Inside rear cover: note about Penguin case for some contemporary point of view. Other Specials [see below] volumes pleading a special cause or advocating a Printers: The Philips Park Press, C.Nicholls and particular solution of political, social and Co. Ltd, London, Manchester, Reading religious dilemmas will appear at intervals in this Price: 1/6d. new series of post-war Penguin Specials ... Front cover: New Series Number One. ... As publishers we have no politics. Some time ago S157 1949 I choose peace. K. Zilliacus we invited a Labour M.P. and a Conservative Specially written for and first published in M.P. to affirm the faith and policy of the two Penguin Books October 1949 principal parties and they did so in two books - pp. [x], [11], 12-509, [510] blank + [2]pp. ‘Labour Marches On’, by John Parker M.P., and adverts. for Penguin Books. Inside front cover ‘The Case for Conservatism’, by Quintin Hogg, [About this Book]. -

Ghost Gig: Redskins Programme

13th December 2019 marks slick, The Redskins were Chris Dean was not keen the anniversary of the highly your band’ and lead singer on broader pop and politics politically charged band Chris Dean once claimed allegiances. Discussing Red Redskins playing our New that his ambition was to Wedge, the Labour Party SETLIST Cavendish Street site. The have his band ‘sing like affiliated movement, he noted original concert took place the Supremes and walk that ‘if the Labour Party are in 1985, only a week after like the clash’ (from NWNM organising a tour, the one thing Lean on Me (second single on CNT, 1982)* 6.15 New Order played the same reissue sleevenotes). Their you can be sure about is that Reds strike the blues* 4.34 venue, and were the subject first single Lev Bronstein it’ll sell out’. He in fact talked Hold on!* 3.18 of a ghost gig last year. As (Trotsky’s real name) was about setting up a Redder Unionise (b side of Lean on Me) 4.53 we noted then, 1985 was a released in 1982, followed by Wedge. Certainly they would Kick over the statues! (single, Decca/London 1985)* 2.27 curious and eclectic musical Lean on Me (‘a love song to have not been interested in decade. For Redskins though workers’ solidarity’ said the the Live Aid event that took Ninety nine and a half won’t do (reissue NWNM) 4.20 1985 would have been seen NME) before the band signed place earlier that summer. Take no heroes!* 5.33 as the year of the SDP/ for Decca/London Records. -

Kiff Aarau We Keep You in the Loop

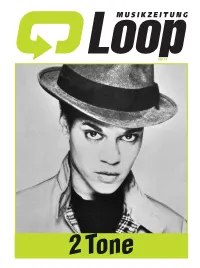

SEP.19 2 Tone EINSCHLAUFEN Betrifft: Unangefochten nach Hause tanzen Impressum Nº 07.19 Die Telefone bleiben stumm, die hastig durch Wipkingen ebenso souverän besteigen wie das DER MUSIKZEITUNG LOOP 22. JAHRGANG den Raum gebrüllten Regieanweisungen sind Nachtboot nach Kairo. Und in lockerer Fuss- verklungen, es ist niemand mehr da. Wilson- bekleidung tanzt man auch unangefochten P.S./LOOP Verlag Pickett-Zeit, Schichtende. Der Kugelschrei- nach Hause, getragen von den Ska-Klängen Hohlstrasse 216, 8004 Zürich ber wird zurück in die Hemdtasche gesteckt, aus den ganz frühen Achtzigerjahren, die uns Tel. 044 240 44 25 der Rechner heruntergefahren, der Schreib- auf den folgenden Seiten begleiten. Eine mu- www.loopzeitung.ch tisch verlassen. Stummen Schrittes durchs sikalische Energiequelle, politisch ummantelt Treppenhaus, zwei Stockwerke, danach vor- und von nachwachsenden Generationen im- bei an der stillgelegten Stempeluhr und raus mer wieder befeuert. Und womöglich erneut Verlag, Layout: Thierry Frochaux in die Sommernacht. «Guido has left the aktuell, wenn Grossbritannien Ende Oktober [email protected] building.» Ein Satz, der jede Nacht kurz in den EU-Austritt umsetzen muss. Denn spä- meinem Kopf aufflackert, gefolgt von einem testens dann wird «You’re Wondering Now» Administration, Inserate: Manfred Müller Blick hoch zum Himmel. von The Specials eine neue Facette erhalten. [email protected] Um diese Uhrzeit ist der Verkehrslärm in un- Ganz zu schweigen von «Ghost Town». serer kleinen grossen Stadt bereits angenehm Noch bleiben also knapp zwei Monate bis Redaktion: Philippe Amrein (amp), gedrosselt, allerdings nicht so stark, dass man zur grossen Abrechnung respektive dem Ab- Benedikt Sartorius (bs), Koni Löpfe sich bloss noch von atmender Stille umgeben schied von Grossbritannien, wie wir es ken- wähnen würde. -

Spring 2018 Picks of the Lists

Spring 2018 Picks of the Lists Boydell & Brewer The Art of Swordsmanship By Hans Medievalism: In A Song Lecküchner of Ice And Fire And Lecküchner, Hans Game Of Thrones Boydell & Brewer/Boydell Carroll, Shiloh Press Boydell & Brewer/D. S. 9781783272914 Brewer Translated by Jeffrey L. 9781843844846 Forgeng. 443 b/w 192 pages illustrations hardcover 488 pages $39.95 paperback Publish Date: 3/1/2018 $25.95 catalog page: 2 Publish Date: 3/1/2018 catalog page: 4 Game of Thrones is famously inspired by the Middle Ages - but how NEW IN PAPERBACK. A vivid modern translation of authentic is the world it presents? a medieval sword fighting manual. This book explores George R. R. Martin’s and HBO’s Completed in 1482, Johannes Lecküchner’s Art of approaches to and beliefs about the Middle Ages Combat with the Langes Messer is among the most and how those beliefs fall into traditional important documents on the combat arts of the medievalist and fantastic literary patterns. It Middle Ages. The Messer was a single-edged, one- analyzes how the drive for historical realism affects handed utility sword peculiar to central Europe, the books’ and show’s treatment of men, women, but Lecküchner’s techniques apply to cut-and- people of colour, sexuality, and imperialism. And thrust swords in general. Not only is this treatise how it has in turn come to define the ‘real’ Middle the single most substantial work on the use of one- Ages for many of its readers and viewers. handed swords to survive from this period, but it is also the most detailed explanation of the SHILOH CARROLL teaches in foundational two-handed sword techniques of the the writing centre at great fourteenth-century master Johannes Tennessee State University. -

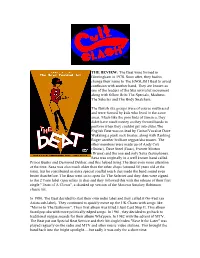

THE REVIEW: the Beat Were Formed in Birmingham in 1978. Soon After, They Had to Change Their Name to the ENGLISH Beat to Avoid Confusion with Another Band

THE REVIEW: The Beat were formed in Birmingham in 1978. Soon after, they had to change their name to The ENGLISH Beat to avoid confusion with another band. They are known as one of the leaders of the Ska revivalist movement along with fellow Brits The Specials, Madness, The Selecter and The Body Snatchers. The British ska groups were of course multiracial and were formed by kids who lived in the same areas. Much like the poor kids of Jamaica, they didnt have much money so they formed bands to perform when they couldnt get into clubs.The English Beat was co-lead by Guitar/Vocalist Dave Wakeling a punk rock toaster, along with Ranking Roger another brilliant reggae/ska toaster. The other members were made up of Andy Cox (Guitar), Dave Steel (Bass), Everett Morton (Drums) and the one and only Saxa (Saxophone). Saxa was originally in a well known band called Prince Buster and Desmond Dekker, and this helped bring The Beat even more attention at the time. Saxa was also much older than the other chaps (around 50 years old at the time), but he contributed an extra special soulful touch that made the band sound even better than before. The Beat went on to open for The Selecter and they then were signed to the 2 Tone label (specialists in ska) and they followed this with the release of their first single "Tears of A Clown", a skanked up version of the Motown Smokey Robinson classic hit. In 1980, The Beat decided to start their own indie label and they called it Go-Feet (an Arista sub-label). -

Warwickshire Cover Online.Qxp Birmingham Cover 24/11/2016 10:32 Page 1

Warwickshire Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 24/11/2016 10:32 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 372 DECEMBER 2016 Warwickshire ’ ONKATHERINE JENKINS WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On warwickshirewhatson.co.uk IN THE MIDLANDS inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide The Belgrade’s annual alternative pantomime p02 (IFC) Warks.qxp_Layout 1 21/11/2016 10:10 Page 1 JAN - FEB 2017 HIGHLIGHTS www.bridgehousetheatre.co.uk 13 JAN, 7.30PM, 25 JAN, 7.30PM, 14 JAN, 2PM FRANKENSTEIN &7.30PM, A brand new adaptation of THE JUNGLE BOOK Mary Shelley’s Gothic horror masterpiece fusing ensemble Rudyard Kipling’s “The storytelling, live music, Jungle Book” is getting the puppetry and stunning Oddsocks treatment! Enjoy theatricality the comical adventures of Calling Wolf-cubs Mowgli the man cub as he everywhere, battles to survive and become the leader of the pack. 29 JAN, 11AM & 2PM, 1 FEB, 7.30PM, THE BOY WHO BIT POLICE COPS PICASSO THE PRETEND MEN’s critically With storytelling, music and acclaimed, multi lots of chances to make your award-winning comedy own art, this hands-on and blockbuster delivers an hilarious family show intro- action packed hour of adren- duces one of the 20th century’s aline most fuelled physical comedy, influential artists through the cinematic style and eyes of a young boy. uncompromising facial hair 16 -17 FEB, 7.30PM, 25 FEB, 12PM & 3PM, MOTIONHOUSE - LAND OF THE SCATTERED DRAGON - This astonishing production ‘GWLAD Y explores our relationship DDRAIG’ with water, a fundamental force in our lives. -

Benny's Babbies

2 1 3 11 12 8 14 13 4 5 28 29 31 9 10 27 7 6 50 51 19 24 93 37 21 22 23 30 36 38 39 52 16 25 26 32 35 49 54 55 56 18 102 20 42 43 73 53 57 62 15 33 86 34 40 46 66 64 95 94 90 89 88 83 82 47 72 65 85 84 81 79 48 58 17 44 74 69 63 101 99 41 45 61 97 92 80 75 71 103 96 78 77 68 100 87 70 98 76 115 67 60 91 120 121 109 59 107 110 114 106 117 118 108 112 105 116 111 113 122 119 104 The Birmingham figures shown in the image are: 1 Steel Pulse (band) 33 Laura Rollins (actress) 65 Lee Child (author) 97 Adrian Lester (actor) 2 Black Sabbath (band) 34 Steve Winwood (musician) 66 Kate Ashfield (actress) 98 Gillian Wearing (artist) 3 Paul Henry (actor) 35 Jeff Rawle (actor) 67 Natalie Haynes (writer/comedian) 99 Duran Duran (band) 4 Cold War Steve (ahem… artist) 36 Jacob Banks (singer) 68 Maizie Williams (model/singer) 100 John Oliver (comedian/TV host) 5 Jemmy (the Rockman) 37 Samuel Anderson (actor) 69 Hard Kaur (rapper) 101 Shefali Chowdhury (actress) 6 James and Oliver Phelps (actors) 38 Alice Amter (actress) 70 Julie Walters (actress) 102 Joe Dixon (actor) 7 Broadcast (band) 39 Hunt Emerson (cartoonist) 71 Donnaleigh Bailey (actress) 103 David Harewood (actor) 8 Apache Indian (rapper) 40 Mr Hudson (musician) 72 Jude Bellingham (footballer) 104 Musical Youth (band) 9 ROMderful (DJ) 41 Jonathan Coe (author) 73 Jack Grealish (footballer) 105 Mist (rapper/grime) 10 The Move (band) 42 Susan Fletcher (author) 74 Anna Brewster (actress) 106 Joe Lycett (comedian) 11 Mike Skinner (musician, rapper, producer) 43 Dr Pogus Caesar (photographer, artist, -

Mmt17 Programme.Pdf

HERTFORD MUSIC FESTIVAL PRESENTS, IN ASSOCIATION WITH Hertford Planning Service Musical Mystery Tour MMT 2 17 Rock’n Stroll... lunchtime to bedtime Sunday 27th Aug at 36 venues all round Hertford town. Programme HERTFORD MUSIC FESTIVAL PRESENTS, IN ASSOCIATION WITH HERTFORD MUSICHertford FESTIVAL PRESENTS, Planning IN ASSOCIATION Service WITH THE HERTFORD MUSIC FESTIVAL HertfordPRESENTS, INHERTFORD ASSOCIATION WITH Planning MUSIC FESTIVAL Service HERTFORD MUSIC FESTIVALPRESENTS, IN ASSOCIATION WITH THEPRESENTS, IN ASSOCIATION WITH Hertford PlanningHertfordTHE Service Planning Service Hertford Planning ServiceTHE HERTFORD MUSIC FESTIVALTHE HERTFORDPRESENTS, MUSIC IN ASSOCIATION FESTIVALWITH HertfordPRESENTS, Planning IN ASSOCIATION WITH Service THE Hertford Planninghardly a venue Service in town that doesn’t take part. What’s THE more, we’re very chuffed to see quite a few veterans Welc me of the MMT (if people well under thirty can be called .com To the 12th Musical Mystery Tour veterans) appearing at major festivals around the world and others becoming bona fide global stars! (You know Eleven years on from our first bash at this way back who you are!). in 2006, we can be pretty confident that the Musical As mentioned on the cover, this programme’s as Mystery Tour is Hertford’s biggest and best musical accurate as possible when going to print a week event by far – going by the numbers of people before the event... But with this numberBank of acts, it’s Holiday Sunday 27th August attending and the fact that these days hotels get almost inevitable that things will change so check the booked up months in advance by people from way website (www.