E Pakihi Hakinga A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Waiata, a Song for the Sacred Mountains and Tribes of Whangārei

Members of the Hātea Kapa Haka group sing a waiata (song) during the unveiling of the Waka and Wave sculpture at the end of the Hīhīaua Peninsular. He waiata, a song for the sacred mountains and tribes of Whangārei Tēnei au ka piki ngā paringa pā tūwatawata, pā maioro o Maunga Parihaka, kia kite atu ngā hapū me ngā maunga tapu e Ka huri whakaterāwhiti ko taku aro ki te kapua hōkaia ki rūnga Maunga Rangitihi Tērā ko Ngāti Pūkenga me Te Tāwera e Ka rere atu au ki te kohu tatao ana i ngā kōhatu teitei o Maunga Manaia, ko Ngai Tāhūhū te iwi e Ka whakarērea te pou o te whare kia tau iho rā ki runga Maunga Rangiora Ko Takahiwai te papakāinga, ko Patuharakeke te hapū e Ka huri whakauta au kia rere atu ki runga Otaika ka tau ki Te Toetoe ko Pā-Te Aroha te marae e Ka hoki whakatehauāuru ki Maunga Tangihua, ki Maunga Whatitiri, ki aku huānga Te Uriroroi me Te Parawhau e Ka huri whakararo taku titiro ki a Ngāti Kahu, ngā uri a Torongare, ko Hurupaki, ko Ngārārātunua, ko Parikiore ngā maunga e Ka haere whakaterāwhiti ki Maunga Maruata me Maunga Pukepoto, kia tau iho ki roto o Ngāti Hau e Tēnei ka hoki ki Maunga Parihaka, kātahi au ka tau iho e Here I climb the embankments of the great fortress Mt. Parihaka that I may see my tribal kinfolk and their sacred mountains Eastward does my gaze turn to the clouds pierced by Mt. Rangitihi, there are Ngāti Pūkenga and Te Tāwera Now I fly onwards to the mists suspended above the lofty peaks of Mt. -

Indicative Coverage of Tourism Locations Under the Mobile Black Spot Fund

Indicative coverage of tourism locations under the Mobile Black Spot Fund Tourism location Region Cape Reinga Northland Glinks Gully Northland Kaeo Northland Maunganui Bluff Northland Ninety Mile Beach Northland Omamari Northland Spirits Bay Northland Takahue Northland Tane Mahuta - Waipoua Forest Northland Urupukapuka Island Northland Utakura: Twin Coast Cycle Trail Northland Wairere Boulders Northland Waitiki Landing Northland Bethells Beach Auckland Aotea Waikato Coromandel Coastal Walkway Waikato Entrances/exits to Pureora Forest Waikato Glen Murray Waikato Marokopa Waikato Mokau Waikato Nikau Cave Waikato Port Charles Waikato Waingaro Waikato Waitawheta Track Waikato Adrenalin Forest Bay of Plenty Bay of Plenty Kaingaroa Forest Bay of Plenty Lake Tarawera Bay of Plenty Maraehako Retreat/Maraehako Bay Bay of Plenty Te Kaha Bay of Plenty Te Wairoa (Buried Village) Bay of Plenty TECT Park (Adrenalin Forest) Bay of Plenty Waitangi (Rotorua) Bay of Plenty Whanarua Bay Bay of Plenty Strathmore Taranaki Tongaporutu Taranaki Blackhead Hawke's Bay Kairakau Beach Hawke's Bay Tutira Hawke's Bay Waihua Hawke's Bay Waipatiki Beach Hawke's Bay Entrances/exits to The Timber Trail Manawatu-Wanganui Owhango Manawatu-Wanganui Pongaroa Manawatu-Wanganui Raurimu Manawatu-Wanganui Cape Palliser Wellington Makara Wellington Cable Bay Nelson Page 1 of 3 Kenepuru Head Marlborough Okiwi Bay Marlborough Blue Lake/ Lake Rotoroa Tasman Cape Farewell Tasman Entrances/exits to Heaphy Track Tasman Lake Rotoroa Tasman Maruia Falls Tasman Totaranui Beach and campsite -

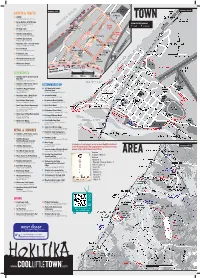

Hokitika Maps

St Mary’s Numbers 32-44 Numbers 1-31 Playground School Oxidation Artists & Crafts Ponds St Mary’s 22 Giſt NZ Public Dumping STAFFORD ST Station 23 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 7448 TOWN Oxidation To Kumara & 2 1 Ponds 48 Gorge Gallery at MZ Design BEACH ST 3 Greymouth 1301 Kaniere Kowhitirangi Rd. TOWN CENTRE PARKING Hokitika Beach Walk Walker (03) 755 7800 Public Dumping PH: HOKITIKA BEACH BEACH ACCESS 4 Health P120 P All Day Park Centre Station 11 Heritage Jade To Kumara & Driſt wood TANCRED ST 86 Revell St. PH: (03) 755 6514 REVELL ST Greymouth Sign 5 Medical 19 Hokitika Craſt Gallery 6 Walker N 25 Tancred St. (03) 755 8802 10 7 Centre PH: 8 11 13 Pioneer Statue Park 6 24 SEWELL ST 13 Hokitika Glass Studio 12 14 WELD ST 16 15 25 Police 9 Weld St. PH: (03) 755 7775 17 Post18 Offi ce Westland District Railway Line 21 Mountain Jade - Tancred Street 9 19 20 Council W E 30 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8009 22 21 Town Clock 30 SEAVIEW HILL ROAD N 23 26TASMAN SEA 32 16 The Gold Room 28 30 33 HAMILTON ST 27 29 6 37 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8362 CAMPCarnegie ST Building Swimming Glow-worm FITZHERBERT ST RICHARDS DR kiosk S Pool Dell 31 Traditional Jade Library 34 Historic Lighthouse 2 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 5233 Railway Line BEACH ST REVELL ST 24hr 0 250 m 500 m 20 Westland Greenstone Ltd 31 Seddon SPENCER ST W E 34 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8713 6 1864 WHARF ST Memorial SEAVIEW HILL ROAD Monument GIBSON QUAY Hokitika 18 Wilderness Gallery Custom House Cemetery 29 Tancred St. -

Tauira Handbook Ngā Hua O Roto Contents

Tauira Handbook Ngā hua o roto Contents He Kupu Whakataki nā Te Taiurungi – welcome from Te Taiurungi ..........................2 Whakatauki – proverbs ...................................................................................................4 Mahere-ā-tau 2019 – important dates ............................................................................5 First connection Mission, Vision, Values ..................................................................................................6 Kaupapa Wānanga ..........................................................................................................7 Pre-enrolment Programme entry criteria / eligibility .............................................................................8 Programme delivery methods ........................................................................................8 Enrolment Acceptance of regulations ............................................................................................10 Privacy of information ..................................................................................................10 Proof of identity .............................................................................................................10 Certified copies of documents .....................................................................................11 Under 18 years of age .................................................................................................. 11 Change of enrolment, late enrolment, withdrawals Change -

Hans Bay Settlement, Lake Kaniere Application for Subdivision and Land Use Consent Lake Kaniere Development Limited

Hans Bay Settlement, Lake Kaniere Application for Subdivision and Land use Consent Lake Kaniere Development Limited Section 88 Resource Management Act 1991 To: Westland District Council PO Box 704 Hokitika 7842 From: Lake Kaniere Development Limited Sunny Bight Road Lake Kaniere Hokitika 7811 See address for service below. 1. Lake Kaniere Development Limited is applying for the following resource consents: RMA Activity Period Sought Section s.11 The subdivision of Lot 2 DP 416269 and unlimited Lot 2 DP 416832 into 51 allotments including allotments to vest as legal road and local purpose reserves. s.9(3) The use of Lot 2 DP 416269 and Lot 2 DP unlimited 416832 and that portion of the unformed legal road heading north from Stuart Street bounded by the boundary of the Small Settlement Zone for the purposes of; construction and formation of legal road as part of Stage 1; clearance of native vegetation and formation of roading, accessway and drainage as part of Stage 2; and the clearance of native vegetation and formation of roading, accessway, drainage and earthbund with cut drain as part of Stage 3 of the development. 2. A description of the activity to which the application relates is: Lake Kaniere Development Limited propose to subdivide two fee simple titles at Hans Bay settlement, Lake Kaniere into a total of 51 allotments. The proposed subdivision comprises 47 residential allotments; two allotments proposed to be vested as local purpose reserves; and two road allotment proposed to be vested in the Westland District Council. Land use consent is also proposed for works associated with the subdivision including vegetation clearance, roading construction and extension to an existing earthbund and cut drain channel. -

Tauira Māori Prospectus 2019 Information for Māori Students and Their Whānau, Schools and Communities Contents

Tauira Māori Prospectus 2019 Information for Māori students and their whānau, schools and communities Contents Nau mai, hāere mai ki Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau We are here to help you 4 The Equity Office – Te Ara Tautika 5-6 How do I get in? 7 The basics 7–8 What is a conjoint degree? 8 Undergraduate Targeted Admission Schemes (UTAS) 10–11 Honouring our Māori alumni 12 Māori student groups 13 Other pathways to study 14 UniBound – Academic Enrichment Programme 14 Foundation programmes 14 Options for Manukau Institute of Technology (MIT) students 14 Scholarships and financial assistance 15 How will the University support me? 17–18 Celebrating Our Village, Our Kāinga 21 2018 Equity events for Māori students 22 It’s time to apply 23 Closing dates for applications Nau mai, hāere mai ki Te Whare for admission in 2018 23 Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau Tū ake i te kei o te waka mātauranga. Tū ake nei i Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau. Nau mai, hāere mai. Welcome to the University of Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand’s world-ranked University.* The University of Auckland offers you a world of This is your opportunity to achieve your goals! opportunities in learning and research. Ko te manu e kai ana i te miro, nōna te ngahere. The University has a strong reputation for Ko te manu e kai ana i te mātauranga, nōna te teaching and research excellence, with national Ao. and international partnerships. As an undergraduate student, you are able to The bird who feeds on miro has the forest. -

Te Kāhui Amokura Tauira Māori Initiatives – Sharing Good Practice in New Zealand Universities

Te Kāhui Amokura Tauira Māori Initiatives – Sharing good practice in New Zealand universities Within all the New Zealand universities there are over 300 This paper looks at four initiatives: initiatives for tauira Māori operating and achieving outstanding results. The drive to ensure tauira Māori are 1. Transition, Academic and Learning Support: Māori successful at university is much deeper than just Health Workforce Development Unit – Tū Kahika improving organisational achievement and retention and Te Whakapuāwai statistics, but rather a genuine commitment to support 2. Māori in STEM: Pūhoro STEM Academy tauira to make a real difference in their life, for their 3. A University Wide Initiative: Tuākana Learning whānau and their wider community. Community 4. Targeted Admission Scheme: Māori and Pasifika In 2016, 16,755 tauira Māori were enrolled within New Admission Scheme (MAPAS) Zealand universities 11% of all domestic students. This is an increase of 19% since 2008. Of those tauira 12,610 These programmes have evidence of success, have a are EFTS (full-time), an increase of 26% since 2008. We strong focus on transition factors and are targeted at first also know that 48% of Māori graduates are the first in year university and secondary school students. their family to attend university, a third are parents and There are useful common findings from these 1 over 70% are female. We acknowledge this progress programmes to be considered for any future initiative within our universities, but always more can be done. development or reviews. -

The Whare-Oohia: Traditional Maori Education for a Contemporary World

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. TE WHARE-OOHIA: TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY WORLD A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Education at Massey University, Palmerston North, Aotearoa New Zealand Na Taiarahia Melbourne 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS He Mihi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 The Research Question…………………………………….. 5 1.2 The Thesis Structure……………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER 2: HISTORY OF TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 9 2.1 The Origins of Traditional Maaori Education…………….. 9 2.2 The Whare as an Educational Institute……………………. 10 2.3 Education as a Purposeful Engagement…………………… 13 2.4 Whakapapa (Genealogy) in Education…………………….. 14 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW 16 3.1 Western Authors: Percy Smith;...……………………………………………… 16 Elsdon Best;..……………………………………………… 22 Bronwyn Elsmore; ……………………………………….. 24 3.2 Maaori Authors: Pei Te Hurinui Jones;..…………………………………….. 25 Samuel Robinson…………………………………………... 30 CHAPTER 4: RESEARCHING TRADITIONAL MAAORI EDUCATION 33 4.1 Cultural Safety…………………………………………….. 33 4.2 Maaori Research Frameworks…………………………….. 35 4.3 The Research Process……………………………………… 38 CHAPTER 5: KURA - AN ANCIENT SCHOOL OF MAAORI EDUCATION 42 5.1 The Education of Te Kura-i-awaawa;……………………… 43 Whatumanawa - Of Enlightenment..……………………… 46 5.2 Rangi, Papa and their Children, the Atua:…………………. 48 Nga Atua Taane - The Male Atua…………………………. 49 Nga Atua Waahine - The Female Atua…………………….. 52 5.3 Pedagogy of Te Kura-i-awaawa…………………………… 53 CHAPTER 6: TE WHARE-WAANANGA - OF PHILOSOPHICAL EDUCATION 55 6.1 Whare-maire of Tuhoe, and Tupapakurau: Tupapakurau;...……………………………………………. -

2019 September Newsletter.Pdf (PDF, 1MB)

West Coast Regional Council SEPTEMBER 2019 Local government elections are Te Tai o Poutini Plan coming soon! On 21 June, the Local Government Reorganisation Scheme Order was gazetted, and the first official Te Tai O Poutini Plan (TTPP) The West Coast region is made up of Committee meeting took place. Recruitment is progressing to three constituencies, represented by seven regional councilors; two from engage a very experienced principal planner as well as for a senior Buller, three from Grey and two from planner to work out of the Regional Council. Westland. By voting you can make a The first task will be undertaking a gap analysis to understand the current district real difference and give your support to plans and what is needed to bring these in to line to meet central government and those candidates who have the values regional policy requirements. This process will also identify what research is required and policies to strengthen our regional to support a robust plan. economy and revitalise our communities. We encourage you to vote as soon as Meetings with lots of stakeholders have been happening over the past few months possible after receiving your voting and a TTPP web page will soon be available on all West Coast Council sites. The web papers in the post so you don’t lose them page will track the progress of the project, and outline and identify opportunities for or run out of time. public engagement throughout the plan’s development. Public meetings will also be held throughout the region as the work gets underway. -

To Be a Forum for the Nation to Present, Explore, and Preserve the Heritage

G.12 ANNUAL REPORT 2008/09 TONGAREWA PAPA TE ZEALAND NEW OF MUSEUM To be a forum for the nation to present, explore, and preserve the heritage of its cultures and knowledge of the natural environment in order to better understand and treasure the past, enrich the present, and meet the challenges of the future… Directory TE RÄRANGI INGOA MUSEUM OF NEW ZEALAND TE PAPA TONGAREWA Cable Street PO Box 467 Wellington 6140 New Zealand TORY STREET RESEARCH AND COLLECTION STORAGE FACILITY 169 Tory Street Wellington 6011 Telephone + 64 4 381 7000 Facsimile + 64 4 381 7070 Email [email protected] Website http://www.tepapa.govt.nz Auditors Audit New Zealand, Wellington, on behalf of the Auditor-General Bankers Westpac Banking Corporation Photography by Te Papa staff photographers, unless otherwise credited ISSN: 1179 – 0024 1 MUSEUM OF NEW OF MUSEUM Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Annual Report 2008/09 Te Pürongo ä-Tau 2008/09 In accordance with section 44 of the Public Finance Act 1989, this annual report of the Museum of TONGAREWA PAPA TE ZEALAND New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa for 2008/09 is presented to the House of Representatives. Contents Ngä Ihirangi ANNUAL Part one Overview Statements Ngä Tauäki Tirohanga Whänui 3 Chairman’s Statement 4 REPORT Acting Chief Executive/Kaihautü Statement 6 Tribute to the late Dr Seddon Bennington (1947–2009) 7 2008/09 Performance at a Glance He Tirohanga ki ngä Whakatutukitanga 8 Part two Operating Framework Te Anga Whakahaere 12 Concept 12 Corporate Principles 12 Functions and Alignment with Government -

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1. CULTURAL HERITAGE THEMES DEVELOPMENT • Foundation Māori Settlement Heritage Theme – Pounamu: To be developed by Poutini Ngāi Tahu with Te Ara Pounamu Project • Foundation Pākehā Settlement Heritage Theme – West Coast Rain Forest Wilderness Gold Rush • Hokitika - Gold Rush Port, Emporium and Administrative Capital actually on the goldfields • Ross – New Zealand’s most diverse goldfield in terms of types of gold deposits and mining methods • Cultural Themes – Artisans, Food, Products, Recreation derived from untamed, natural wilderness 2. TOWN ENVIRONMENT ENHANCEMENTS 2.1 Hokitika Revitalisation • Cultural Heritage Precincts, Walkways, Interpretation, Public Art and Tohu Whenua Site • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 2.2 Ross Enhancement • Enhancement and Experience Plan Development • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 3. COMMERCIAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT • Go Wild Hokitika and other businesses at TRENZ 2020 • Chinese Visitor Business Cluster • Mahinapua Natural and Cultural Heritage Iconic Attraction 4. COMMUNITY OWNED BUSINESSES AND ACTIVITIES • Westland Industrial Heritage Park Experience Development • Ross Goldfields Heritage Centre and Area Experience Development 5. MARKETING • April 2020 KUMARA JUNCTION to GREYMOUTH Taramakau 73 River Kapitea Creek Overview of the Westland CulturalCHESTERFIELD Heritage 6 KUMARA AWATUNA Londonderry West Coast Rock Tourism Development Plan Wilderness Trail German Gully -

Culture and the Place of Haka in Commemoration at Gallipoli

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2015 Me Haka I te Haka a Tānerore?: Māori 'Post-War' Culture and the Place of Haka in Commemoration at Gallipoli Hemopereki Simon University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Simon, Hemopereki, "Me Haka I te Haka a Tānerore?: Māori 'Post-War' Culture and the Place of Haka in Commemoration at Gallipoli" (2015). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 2971. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/2971 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Me Haka I te Haka a Tānerore?: Māori 'Post-War' Culture and the Place of Haka in Commemoration at Gallipoli Abstract This article is an extensive discussion from a Maori perspective into issues around the use of Maori cultural terms, in particular haka, to commemorate the fallen in WWI. Embedded in the article are key theories of cultural memory, 'war culture' and 'post-war culture'. The research outlines the differences between European and Indigenous war and post war cultural practices focusing on Maori. It seeks to understand the reluctance of Turkish officials to see haka being performed when it was apparently banned from ceremonies in 2005. It outlines the media reporting on the issue and the subsequent reintroduction of haka in August 2015 at the centenary of the Chunuk Bair battle.