A Comparative Analysis of the Copyright Law of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home of the World Trade Organization Geneva Foreword

Home of the World Trade Organization Geneva Foreword THIS BOOK ON THE HISTORY AND WORKS OF ART of the Centre William Rappard of the works, donated by countries and labour would not have been possible ten years ago. The reason for this is simple: despite unions during the ILO era, had been either the building’s rich past, illustrious occupants and proud appearance, it was a little concealed or removed. In restoring these works, antiquated and not particularly well known or even well liked. Located in a magnificent the WTO took on an identity that was not strictly park on the shore of Lake Geneva, with a spectacular view of the Alps, it has a speaking its own, but of which its staff and somewhat turbulent past. Members have become proud. AS THE FIRST BUILDING IN GENEVA built to house an international organization, THE WORKS OF ART PRESENTED IN THIS BOOK , many of which have been the Centre William Rappard, named after a leading Swiss diplomat, was originally given a new lease of life by the WTO, display a wide variety of styles and techniques. the headquarters of the International Labour Office (ILO). The ILO left the building Many of them represent labour in its various forms – an allusion, of course, to the in 1940 during the Second World War, but later moved back in 1948, only to leave activities of the ILO, the building’s original occupant. Other works, such as Eduardo for good in 1975 when the Centre William Rappard was handed over to its new Chicharro’s “Pygmalion”, are more unusual. -

Understanding the WTO

The WTO Third edition Previously published as “Trading into the Future” Location: Geneva, Switzerland Written and published by the Established: 1 January 1995 World Trade Organization Information and Media Relations Division Created by: Uruguay Round negotiations (1986–94) © WTO 1995, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007 Membership: 150 countries (since 11 January 2007) Budget: 175 million Swiss francs for 2006 An up-to-date version of this text also appears on the WTO website (http://www.wto.org, click on “the WTO”), where it is Secretariat staff: 635 regularly updated to reflect developments in the WTO. Head: Pascal Lamy (director-general) Contact the WTO Information Division rue de Lausanne 154, CH–1211 Genève 21, Switzerland Functions: Tel: (41–22) 739 5007/5190 • Fax: (41–22) 739 54 58 • Administering WTO trade agreements e-mail: [email protected] • Forum for trade negotiations Contact WTO Publications • Handling trade disputes rue de Lausanne 154, CH–1211 Genève 21, Switzerland • Monitoring national trade policies Tel: (41–22) 739 5208/5308 • Fax: (41–22) 739 5792 e-mail: [email protected] • Technical assistance and training for developing countries • Cooperation with other international organizations February 2007 — 6 000 copies Understanding the WTO 3rd edition Previously published as “Trading into the Future” September 2003, revised February 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Some of the abbreviations and acronyms used in the WTO: ITC International Trade Centre ITO International Trade Organization ACP African, Caribbean and Pacific Group MEA Multilateral -

Diagnosis: Selection at the World Trade Organization

3 Diagnosis: Selection at the World Trade Organization Conflict over leadership selection at the IMF and the World Bank did not result from flaws in the formal governance of those organizations. A combination of weighted voting and informal agreement that narrow majorities and formal votes were to be avoided enabled these organizations in the end to surmount conflict and produce new leadership. Restric- tions on selection that had been imposed by the dominant members, a product of their decision-making weight within the organization, were the principal source of conflict. Whether or not that dual monopoly—the convention—will persist is the central question for future leadership selection in these organizations. Conflict over leadership selection at the WTO in the 1990s had very different sources. Although the field of candidates in each selection might have been larger or, some would argue, more distinguished or expert, certainly there were few restrictions on the pool of candidates. Unlike the IFIs, lack of competition was not a problem at the WTO. Rather, active and open competition for the top position in the organization could not be resolved. Instead of consensus on a new director-general, the WTO found prolonged deadlock and increasingly bitter division. Conflict fi- nally produced a director-general with a shortened term in one instance (Renato Ruggiero, 1995) and in a second case, two directors-general with even shorter terms as part of a term-sharing agreement (Mike Moore and Supachai Panitchpakdi). Leadership selection is only one aspect of a broader crisis of decision making at the WTO. Solving recurrent conflict and stalemate over selection of the director-general will finally require a deeper reform of decision making at the organization. -

Wiggle Rooms: New Issues and North-South Negotiations During the Uruguay Round

Wiggle Rooms: New Issues and North-South Negotiations during the Uruguay Round J. P. Singh Communication, Culture and Technology Program Georgetown University 3520 Prospect Street, NW, Suite 311 Washington, DC 20057 Ph: 202/687-2525 Fax: 202/687-1720 E-mail: [email protected] Research support for this paper was provided through the Social Science Research Council’s Summer Fellowship Program on ‘Information Technology, International Cooperation, and Global Security’ held at Columbia University and a competitive research grant from Georgetown University. My thanks to the SSRC fellows in the summer program for their input. I am also grateful to John Odell and Susan Sell for help with this project. Previous versions of this paper were presented to the Washington Interest in Negotiations (WIN) group and the 2003 American Political Science Association, which provided important feedback. My thanks to the discussants Beth Yarborough, and William Zartman. Prepared for the conference on Developing Countries and the Trade Negotiation Process, 6 and 7 November 2003, UNCTAD, Palais des Nations, Room XXVII, Geneva COMMENTS WELCOME. Please ask author’s permission before citing. 1 Are developing countries marginalized in the formation of global rules governing new issues such as services and intellectual property rights?1 Not if they are savvy negotiators and the developed countries are not unified in their stance, suggests this study. Analysts examine the gains developing countries make in such ‘high-tech’ issue areas (Grieco 1982; Odell 1993; Singh 2002A) to note that the weak do not necessarily suffer the will of the strong. Their success with high-tech negotiations, in fact, bodes well for them in issue areas in which they are strong (for example, agriculture or textiles). -

Uruguay Round Matthias Oesch

Uruguay Round Matthias Oesch Content type: Encyclopedia entries Product: Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law [MPEPIL] Article last updated: April 2014 Subject(s): Tariffs — Developing countries — National treatment — Most-favoured-nation treatment (MFN) — Goods — Subsidies — Technical barriers to trade — Specific trade agreements Published under the auspices of the Max Planck Foundation for International Peace and the Rule of Law under the direction of Rüdiger Wolfrum. From: Oxford Public International Law (http://opil.ouplaw.com). (c) Oxford University Press, 2015. All Rights Reserved. Subscriber: UZH Hauptbibliothek / Zentralbibliothek Zurich; date: 09 August 2019 A. Negotiations 1 The Uruguay Round was the eighth post-war multilateral trade negotiation conducted under the → General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947 and 1994) (‘GATT 1947’ and ‘GATT 1994’; see also → International Economic Law). It started with a Ministerial Meeting held in Punta del Este in Uruguay on 20 September 1986. The → Final Act and the texts annexed were eventually signed in Marrakesh, Morocco, on 15 April 1994, and entered into force on 1 January 1995. This round led to the creation of the → World Trade Organization (WTO). For the first time, multilateral trade negotiations covered virtually every sector of world trade. Moreover and equally unprecedented, participation by both industrialized and → developing countries was truly global. Overall, the Uruguay Round was the largest trade negotiation ever, and it resulted in a historic quantum leap in institutionalized global economic cooperation. 1. Launch 2 One of the essential functions of the GATT 1947 framework was to host a series of major multilateral trade negotiation rounds. The first six of these rounds were concerned mainly with the reduction of tariffs (Geneva Conference 1947; Annecy Conference 1949; Torquay Conference 1950–51; Geneva Conference 1956; Geneva Conference [also known as Dillon Round] 1960–61; Kennedy Round 1964–67). -

LAW WP Template 2013 2012

LAW 2013/10 Department of Law The Establishment of a GATT Office of Legal Affairs and the Limits of ‘Public Reason’ in the GATT/WTO Dispute Settlement System Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann European University Institute Department of Law The Establishment of a GATT Office of Legal Affairs and the Limits of ‘Public Reason’ in the GATT/WTO Dispute Settlement System Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann EUI Working Paper LAW 2013/10 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1725-6739 © Ernst-Ulrich Petersmann, 2013 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract: The article offers an ‘insider story’ of the establishment of the Office of Legal Affairs in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947) in 1982/83 and of its increasing involvement in assisting GATT dispute settlement panels and the Uruguay Round negotiations on a new World Trade Organization with compulsory jurisdiction for the settlement of trade disputes (Sections I and II). The transformation, within only one decade, of the anti-legal pragmatism in GATT 1947 into the compulsory WTO dispute settlement system amounted to a ‘revolution’ in international law. But the ‘public -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Bargaining Power in Multilateral Trade Negotiations: Canada and Japan in Th

The London School of Economics and Political Science Bargaining power in multilateral trade negotiations: Canada and Japan in the Uruguay Round and Doha Development Agenda. Jens Philipp Anton Lamprecht A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, January 2014 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 95676 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Trevor G. Cooper. Signed: Jens Philipp Anton Lamprecht. 2 In memory of my grandparents, Antonette Dinnesen and Heinrich Dinnesen. To my family: My parents, my brother, my aunt, and Hans-Werner am Zehnhoff. 3 Acknowledgements Very special thanks go to my supervisors, Dr. Razeen Sally and Dr. Stephen Woolcock. I thank Razeen for his constant patience, especially at the beginning of this project, and for his great intellectual advice and feedback. -

Leaders, Artists and Spies

aCdentre WilliameRappard r arpixtr nd s e s over Brussels and other European cities as the seat of the League of Nations and the International Labour Office. He maintained that various international institutions and movements were enticed by the “splendor and charm of her [Geneva’s] natural surroundings, by her moral and intellectual traditions of freedom, and by the independence and the very insignificance of her political status”. 5 Rappard was appointed member of the Mandates Commission in the League of Nations (1920-1924), Swiss delegate to the International Taking Labour Office, and later to the United Nations Organization. During World War II, Rappard took an active part in the work of the International Committee for the Placing of Refugee Intellectuals, set up in Geneva in 1933. As professor of economic history at the University of Geneva, Centre Stage Rappard taught public finance and international relations. He was twice Rector of the University of Geneva and, with Paul Mantoux, co-founder If it is true that “the artist is not a special kind of man, but every man is a special kind of of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, where he taught from 1928 to 1955. William Rappard died on 29 April 1958 in Geneva. The artist”, 4 then numerous people who have worked at the Centre William Rappard have Centre William Rappard and the Chemin William Rappard in Bellevue, greatly contributed to the building’s rich history. This chapter opens with short biographies of a town near Geneva, were named after him. a selection of civil servants who have made a special contribution to the history of the building, including William Rappard, the ILO’s first Directors-General Albert Thomas and Harold Butler, and GATT Directors-General Eric Wyndham White, Olivier Long and Arthur Dunkel. -

40TH ANNIVERSARY, 30 OCTOBER 1987 GATT/40/1 Page 2/3

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE \CCORD GÉNÉRAL SUR LES TARIFS )UANIERS ET LE COMMERCE CENTRE WILLIAM-RAPPARD, 154, RUE DE LAUSANNE, 1211 GENÈVE 21, TEL. W? ,11 0233 022 39 51 11 GATT/40/1 GATT - THE FIRST FORTY YEARS by Arthur Dunkel, Director-General of GATT "In the first year that the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was in effect, 1948, the value of world trade amounted to some US$57 billion. In 1986, it was worth more than US$2,100 billion. Over the same period, the volume of trade in manufactured goods multiplied more than twenty times. That is a lot of trade to keep moving but, simply stated, that is exactly GATT's role. "GATT can be regarded as providing the highway rules for world trade. Traffic will only flow freely if drivers not only agree on the rules of the road but actually obey them. The rules of GATT are simple in essence. They provide for non-discrimination, fair competition, the rational settlement of disputes, trade liberalization, the use of tariffs rather than quotas and so on. When they are permitted to work, world trade can expand in a healthy manner and traders and investors can make plans and take decisions with reasonable confidence and security. And consumers benefit also. "The idea of a multilateral set of rules governing national trade policies and international trade relations was not new in the 1940s, but it was only after the great depression of the 1930s and the trauma of the MORE 87-1591 40TH ANNIVERSARY, 30 OCTOBER 1987 GATT/40/1 Page 2/3 second world war - which could be said to have had some of its roots in protectionist and nationalistic economic policies - that governments had the courage and ability to transform the idea into reality. -

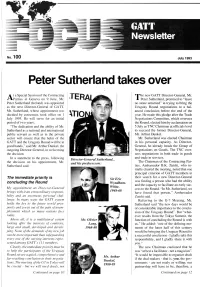

Peter Sutherland Takes Over

GATT Newsletter No 100 July 1993 Peter Sutherland takes over t a Special Session of the Contracting he new GATT Director-General, Mr. AParties in Geneva on 9 June, Mr. TER TPeter Sutherland, promised to "leave Peter Sutherland (Ireland) was appointed no stone unturned" in trying to bring the as the next Director-General of GATT. Uruguay Round negotiations to a bal Mr. Sutherland, whose appointment was anced conclusion before the end of the decided by consensus, took office on l year. He made this pledge after the Trade July 1993. He will serve for an initial Negotiations Committee, which oversees period of two years. the Round, elected him by acclamation on "The dedication and the ability of Mr. 5 July as TNC Chairman at officials level Sutherland as a national and international to succeed the former Director-General, public servant as well as in the private Mr. Arthur Dunkel. sector will ensure that the helm of the Mr. Sutherland was elected Chairman GATT and the Uruguay Round will be in in his personal capacity. As Director- good hands," said Mr. Arthur Dunkel, the General, he already heads the Group of outgoing Director-General, in welcoming Negotiations on Goods. The TNC over the decision. sees negotiations in both trade in goods and trade in services. In a statement to the press, following Director-General Sutherland., The Chairman of the Contracting Par the decision on his appointment, Mr. and his predecessors: Sutherland said: ties, Ambassador B.K. Zutshi, who in itially chaired the meeting, noted that one principal criterion of GATT members in their search for a new Director-General The immediate priority is Sir Eric concluding the Round was finding a person who had the ability Wyndham- and the capacity to facilitate an early suc My appointment a's Director-General White, cess to the Round. -

The Impact of Policy Networks in the Gatt Uruguay Round: the Case of the Us-Ec Agricultural Negotiations

THE IMPACT OF POLICY NETWORKS IN THE GATT URUGUAY ROUND: THE CASE OF THE US-EC AGRICULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS HEIDI KAREN ULLRICH LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENTS OF GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL SATISFACTION OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2002 1 UMI Number: U174118 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U174118 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 r:^ POLITICAL & AN° 4 f Zou 9fe^7o) ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the membership, activities and policy impact of three distinct groups of policy networks operating within and between the agricultural policy environments of the US and EC as well as at the multilateral level during the preparation for and negotiations of the GATT Uruguay Round between 1980 and 1993. Briefly defined, these three groups are: 1) epistemic communities - networks of professionals who share both specialized knowledge and expertise in a specific issue area; 2) advocacy coalitions - policy actors from various levels of the policy process who share common policy beliefs and work together to turn these policy beliefs into government policy; and 3) elite transnational networks - incorporating political leaders, political appointees and senior government and international institutional officials, these elite level networks are formed through regular contact in either an official or unofficial capacity.