The United States' Involvement in Haiti's Tragedy and the Resolve to Restore Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Right to Vote – Haiti 2010/2010 Elections

2010/ 2011 The Right to Vote A Report Detailing the Haitian Elections for November 28, 2010 and March, 2011 “Voting is easy and marginally useful, but it is a poor substitute for democracy, which requires direct action by concerned citizens.” – Howard Zinn Human Rights Program The Right to Vote – Haiti 2010/2011 Elections Table of Contents Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Permanent vs. Provisional .......................................................................................................................... 2 Government in Shambles ............................................................................................................................ 2 November Elections .................................................................................................................................... 3 March Elections.......................................................................................................................................... 3 Laws Governing The Elections Process ......................................................................................................... 4 Constitution ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Electoral Law ............................................................................................................................................ -

Haiti: a Case Study of the International Response and the Efficacy of Nongovernmental Organizations in the Crisis

HAITI: A CASE STUDY OF THE INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE AND THE EFFICACY OF NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS IN THE CRISIS by Leslie A. Benton* Glenn T. Ware** I. INTRODUCTION In 1990, a military coup ousted the democratically-elected president of Haiti, Jean- Bertrand Aristide. The United States led the international response to the coup, Operation Uphold Democracy, a multinational military intervention meant to restore the legitimate government of Haiti. The operation enjoyed widespread support on many levels: the United Nations provided the mandate, the Organization of American States (OAS) supported it, and many countries participated in the multinational force and the follow-on United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH). International, regional, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) worked with the multinational force and later the UNMIH to restore the elected government and to provide humanitarian assistance to the people of Haiti. This article focuses on the latter aspect of the international response–the delivery of humanitarian aid. It closely examines the methods of interorganization coordination,[1] with particular attention given to the interaction among NGOs and the United States military. An examination of that relationship indicates that the infrastructure the military used to coordinate with the NGO community–the Civil Military Operations Center (CMOC)–was critical to the success of the humanitarian mission. Because both the military and the humanitarian community will probably have to work together again in humanitarian assistance operations in response to civil strife, each community must draw on the lessons of past operations to identify problems in coordination and to find solutions to those problems. II. THE STORY A. Haiti’s History: 1462-1970[2] Modern Haitian history began in 1492 when Christopher Columbus landed on Haiti near Cape Haitien on the north coast of Hispaniola.[3] At first, the island was an important colony and the seat of Spanish government in the New World, but Spain’s interest in Hispaniola soon waned. -

January 17 – 23, 2006

HAITI NEWS ROUNDUP: JANUARY 17 – 23, 2006 Haitian presidential hopeful decries gap between rich and poor 23 January 2006 AFP PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (AFP): Haiti's elites must do more to help the poor, the frontrunner in Haiti's presidential race told AFP in an interview. "If those who have, begin to invest in the education of the weakest among us, they would be grateful," said former president Rene Preval, who leads opinion polls ahead of the February 7 election. "Children must be taken off the streets. Weapons must be taken from the hands of children and replaced with pens and books," he said late on Friday. "That is how we will harmonize relations between rich and poor." Cite Soleil, a sprawling slum in the capital that is controlled by armed groups, represents the failure of the country's elites, he said. "We must realize it," he said. "The rich are cloistered in their walled villas and the poor are crammed into slums and own nothing. The gap is too big," he said. Preval opposed a military solution to the problems posed by Cite Soleil, the source of much of Haiti's ongoing insecurity. "I am against a military solution to this problem," he said in an interview late Friday, proposing dialogue, "intelligence and firmness" instead. Preval called for judicial reform, the expansion of Haiti's 4,000-strong police force and for the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) to remain in place until Haitians can ensure stability themselves. " Those that want to create instability in the country and to continue drug trafficking will be the first to demand MINUSTAH's departure. -

Report on Haiti, 'Failed Justice Or Rule of Law?'

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser/L/V/II.123 doc.6 rev 1 26 October 2005 Original: English HAITI: FAILED JUSTICE OR THE RULE OF LAW? CHALLENGES AHEAD FOR HAITI AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY GENERAL SECRETARIAT ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES WASHINGTON D.C. 2006 2006 http://www.cidh.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Haiti: Failed Justice or the Rule of Law? Challenges Ahead for Haiti and the International Community 2005 / Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. p. ; cm. (OAS Official Records Series. OEA Ser.L/V/II.123) ISBN 0-8270-4927-7 1. Justice, Administration of--Haiti. 2. Human rights--Haiti. 3. Civil rights--Haiti. I. Title. II Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.123 (E) HAITI: FAILED JUSTICE OR THE RULE OF LAW? CHALLENGES AHEAD FOR HAITI AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. v I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................5 II. BACKGROUND ..............................................................................6 A. Events in Haiti, 2003-2005 ..................................................6 B. Sources of Information in Preparing the Report ..................... 11 C. Processing and Approval of the Report................................. 14 III. ANALYSIS OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN HAITI ............ 17 A. Context for Analysis .......................................................... 17 -

Report on the Parliamentary Field Mission

130th IPU ASSEMBLY AND RELATED MEETINGS Geneva, 16 – 20.3.2014 Standing Committee on United Nations Affairs March 2014 ADVISORY GROUP OF THE IPU COMMITTEE ON UNITED NATIONS AFFAIRS Mission by the Advisory Group of the IPU Committee on United Nations Affairs Haiti, 24-27 February 2014 Report of the Mission to Haiti The Advisory Group of the IPU Committee on United Nations Affairs undertook a field mission to Haiti from 24 to 27 February 2014. Its mandate was to examine United Nations stabilization and humanitarian efforts in the country, the manner in which efforts at the country level meet the needs and expectations of the local population, as well as the effectiveness of these operations. The mission also looked at how UN partners on the ground involve parliament, and more specifically the role parliament plays in helping secure the rule of law, as well as peace and sustainable development in the country. The visit was part of a series of missions undertaken by the Advisory Group since its establishment in 2008, designed to assess the degree to which national parliaments were aware of and involved in major UN initiatives in their respective countries, such as One UN reform to align international support to the priorities established by national authorities. These include visits to: Tanzania in 2008, Viet Nam in 2009, Ghana and Sierra Leone in 2011, Albania and Montenegro in 2012), and Côte d’Ivoire in 2013. The mission to Haiti was aimed at examining stabilization efforts in the country and the humanitarian operations led by MINUSTAH. The parliamentary delegation was led by Mr. -

Preliminary Statement Issed by the CARICOM Electoral Observer

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT OF THE CARICOM ELECTION OBSERVER MISSION (CEOM) ON THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS OF HAITI ON 25 OCTOBER 2015 The CARICOM Election Observation Mission (CEOM) comprised: Dr. Steve Surujbally, Chairman of the Guyana Elections Commission (Chief of Mission) Mr Ian Hughes, Registration Officer, Antigua & Barbuda Electoral Commission; Mr Geoffrey McPhee, Assistant to the Parliamentary Commissioner of The Bahamas; Mr Rudolph Waterman, Senior Executive Officer, Barbados Election Commission; Mr Henry George, Former Parliamentarian of Dominica; Mr Michael Flood, Commissioner, Electoral Commission of Saint Lucia; Mr Clement St Juste, Commissioner, Electoral Commission of Saint Lucia; and Ms. Neisha Ali-Harrynarine, Assistant Chief Election Officer (Ag), of Trinidad and Tobago. The staff members from the CARICOM Secretariat who provided support to the Mission were Ms Tricia Barrow and Ms Denise London. MEETINGS During the periods before, during and immediately after Elections Day, meetings were held with: H.E. Hon. Prime Minister of Haiti, Mr. Evans Paul; The Hon. Minister delegate for Electoral Affairs, Mr. Jean Fritz Jean Louis; The General Coordinator of the National Council for Electoral Observation (CNO), Mr. Patrick Labb and his colleague Mr. Gédéon Paul; Member of the National Network for the Defense of Human Rights (RNDDH), Ms. M. Jean; The President of the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP), Mr. Pierre Louis Opont; The European Union’s officers stationed in Haiti, and members of the EU Observer Team; The Chef de Mission of the OAS Team and Members of the OAS Observer Mission; The Chef de Mission of PARLAMERICAS’ Elections Observer Term, Mr. Alain Gauthier; Special Representative of the Secretary General of the United Nations (SRSG), H.E. -

Haiti Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Haiti Country Report Status Index 1-10 3.46 # 114 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.75 # 97 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 3.18 # 116 of 129 Management Index 1-10 3.44 # 109 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Haiti Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Haiti 2 Key Indicators Population M 10.6 HDI 0.471 GDP p.c., PPP $ 1731.8 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.3 HDI rank of 187 168 Gini Index 60.8 Life expectancy years 63.1 UN Education Index 0.374 Poverty3 % 71.0 Urban population % 57.4 Gender inequality2 0.599 Aid per capita $ 112.2 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Since the end of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, Haiti has lived through recurrent circles of crises and the nation’s social and political elites are trapped in a vicious circle of mistrust and zero- sum politics. -

Written Testimony of Pierre Esperance Executive Director Haitian National Human Rights Defense Network (Réseau National De Défense Des Droits Humains, RNDDH)

Written Testimony of Pierre Esperance Executive Director Haitian National Human Rights Defense Network (Réseau National de Défense des Droits Humains, RNDDH) Submitted to the Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Civilian Security, and Trade House Foreign Affairs Committee Hearing on “Haiti on the Brink: Assessing U.S. Policy Toward a Country in Crisis” December 10, 2019 Interpretation conducted by Hyppolite Pierre Chairman Sires, Ranking Member Rooney, and other distinguished Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for holding this important hearing on the ongoing situation in Haiti. My name is Pierre Esperance, the Executive Director of the Haitian National Human Rights Defense Network (RNDDH), a human rights education and monitoring organization devoted to ensuring the protection of rights and the upholding of rule of law in Haiti, and I am grateful for the opportunity to be here today. To begin, the general human rights situation in Haiti is characterized by a worrying security situation, the proliferation of armed gangs protected by the state – otherwise known as the gangsterization of the state, the dysfunction of the Haitian judiciary, impunity, corruption across all state institutions, the repression of anti-government demonstrations and the absence of any political will to find lasting solutions to the many problems facing the country. 1. On insecurity Haiti faces severe security challenges that affect all Haitians. One major cause of concern is the ongoing gangersterization of the state. Currently, from the capital to provincial cities, Haiti is full of armed gangs that enjoy the protection of the executive and legislative powers. They regularly receive money and automatic firearms, and they never run out of ammunition. -

The Bulletin

THE BULLETIN The Bulletin is a publication of the European Commission for Democracy through Law. It reports regularly on the case-law of constitutional courts and courts of equivalent jurisdiction in Europe, including the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Communities, as well as in certain other countries of the world. The Bulletin is published three times a year, each issue reporting the most important case-law during a four month period (volumes numbered 1 to 3). The three volumes of the series are published and delivered in the following year. Its aim is to allow judges and constitutional law specialists to be informed quickly about the most important judgments in this field. The exchange of information and ideas among old and new democracies in the field of judge-made law is of vital importance. Such an exchange and such cooperation, it is hoped, will not only be of benefit to the newly established constitutional courts, but will also enrich the case-law of the existing courts. The main purpose of the Bulletin on Constitutional Case-law is to foster such an exchange and to assist national judges in solving critical questions of law which often arise simultaneously in different countries. The Commission is grateful to liaison officers of constitutional and other equivalent courts, who regularly prepare the contributions reproduced in this publication. As such, the summaries of decisions and opinions published in the Bulletin do not constitute an official record of court decisions and should not be considered as offering or purporting to offer an authoritative interpretation of the law . -

Yvon Neptune V. Haiti Judgment of May 6, 2008 (Merits, Reparations and Costs)

Inter-American Court of Human Rights Case of Yvon Neptune v. Haiti Judgment of May 6, 2008 (Merits, Reparations and Costs) In the case of Yvon Neptune, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Inter-American Court” or “the Court”) composed of the following judges: Cecilia Medina Quiroga, President Diego García-Sayán, Vice President Sergio García Ramírez, Judge Manuel E. Ventura Robles, Judge Leonardo A. Franco, Judge Margarette May Macaulay, Judge, and Rhadys Abreu Blondet, Judge; also present, Pablo Saavedra Alessandri,Secretary, and Emilia Segares Rodríguez, Deputy Secretary; pursuant to Articles 62(3) and 63(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention” or “the American Convention”) and Articles 29, 31, 53(2), 55, 56 and 58 of the Court’s Rules of Procedure (hereinafter “the Rules of Procedure”), delivers this judgment. I INTRODUCTION OF THE CASE AND SUBJECT OF THE DISPUTE 1. On December 14, 2006, in accordance with the provisions of Articles 50 and 61 of the American Convention, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or “the Inter-American Commission”) submitted an application to the Court against the Republic of Haiti (hereinafter “the State” or “Haiti”) in relation to case no. 12,514. The application originated from petition No. 445/05, submitted to the Secretariat of the Commission on April 20, 2005, by Brian Concannon Jr., Mario Joseph and the Hastings Human Rights Project for Haiti. On October 12, 2005, the Commission adopted Admissibility Report No. 64/05, and on July 20, 2006 it adopted Report on Merits No. -

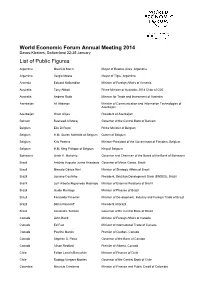

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Presidency of the Republic of Haiti

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unitlltt^^^clT1B/^d^^GExMWM3NWYzLTk0NJk- - STATEMENT ON THE ASSASSINATION OF HAITIAN PRESIDENT JOVENEL MOISE Djenny Passe (Mercury) <[email protected]> Wed 7/7/2021 10:04 AM To: Djenny Passe (Mercury) <[email protected]> Bcc: KD <[email protected]>; Craig Ferriman <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]> | 1 attachments (58 KB) STATEMENT ON THE ASSASSINATION OF HAITIAN PRESIDENT JOVENEL MOISE.pdf; Hello, Please find attached a statement from Prime Minister Claude Joseph on the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moise. Mercury. Djenny Passe Vice President 200 Varick Street Suite 600 New York, NY 10014 212.681.1380 office 516.243.4995 mobile www.mercurvllc.com Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/09/2021 11:33:56 AM 7/8/21,10:21 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/09/2021 11:33:54 AM STATEMENT ON THE ASSASSINATION OF HAITIAN PRESIDENT JOVENEL MOISE It is with deep sorrow that the Government of Haiti can confirm that President Moise has been assassinated.