Reducing Stress Via Three Different Group Counseling Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges

DANIEL NETTLE Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life D ANIEL Essays on Science, Society I love this book. I love the essays and I love the overall form. Reading these essays feels like entering into the best kind of intellectual conversati on—it makes me want and the Academic Life to write essays in reply. It makes me want to get everyone else reading it. I almost N never feel this enthusiasti c about a book. ETTLE —Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cogniti ve Science at MIT What does it mean to be a scien� st working today; specifi cally, a scien� st whose subject ma� er is human life? Scien� sts o� en overstate their claim to certainty, sor� ng the world into categorical dis� nc� ons that obstruct rather than clarify its complexi� es. In this book Daniel Ne� le urges the reader to unpick such DANIEL NETTLE dis� nc� ons—biological versus social sciences, mind versus body, and nature versus nurture—and look instead for the for puzzles and anomalies, the points of Hanging on to the Edges connec� on and overlap. These essays, converted from o� en humorous, some� mes autobiographical blog posts, form an extended medita� on on the possibili� es and frustra� ons of the life scien� fi c. Pragma� cally arguing from the intersec� on between social and biological sciences, Ne� le reappraises the virtues of policy ini� a� ves such as Universal Basic Income and income redistribu� on, highligh� ng the traps researchers and poli� cians are liable to encounter. -

The Mixtape: a Case Study in Emancipatory Journalism

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE MIXTAPE: A CASE STUDY IN EMANCIPATORY JOURNALISM Jared A. Ball, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Directed By: Dr. Katherine McAdams Associate Professor Philip Merrill College of Journalism Associate Dean, Undergraduate Studies During the 1970s the rap music mixtape developed alongside hip-hop as an underground method of mass communication. Initially created by disc-jockeys in an era prior to popular “urban” radio and video formats, these mixtapes represented an alternative, circumventing traditional mass medium. However, as hip-hop has come under increasing corporate control within a larger consolidated media ownership environment, so too has the mixtape had to face the challenge of maintaining its autonomy. This media ownership consolidation, vertically and horizontally integrated, has facilitated further colonial control over African America and has exposed as myth notions of democratizing media in an undemocratic society. Acknowledging a colonial relationship the writer created FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show where the mixtape becomes both a source of free cultural expression and an anti-colonial emancipatory journalism developed as a “Third World” response to the needs of postcolonial nation-building. This dissertation explores the contemporary colonizing effects of media consolidation, cultural industry function, and copyright ownership, concluding that the development of an underground press that recognizes the tremendous disparities in advanced technological access (the “digital divide”) appears to be the only viable alternative. The potential of the mixtape to serve as a source of emancipatory journalism is studied via a three-pronged methodological approach: 1) An explication of literature and theory related to the history of and contemporary need for resistance media, 2) an analysis of the mixtape as a potential underground mass press and 3) three focus group reactions to the mixtape as resistance media, specifically, the case study of the writer’s own FreeMix Radio: The Original Mixtape Radio Show. -

Muck Vegetable Cultivar Trial & Research Report 2010

Muck Vegetable Cultivar Trial & Research Report 2010 M.R. McDonald S. Janse L. Riches M. Tesfaendrias K. Vander Kooi Office of Research & Muck Crops Dept. of Plant Agriculture Research Station Report No. 60 Kettleby, Ontario Research and Cultivar Trial Report for 2010 University of Guelph Office of Research & Department of Plant Agriculture Muck Crops Research Station 1125 Woodchoppers Lane R.R. # 1 Kettleby, Ontario L0G 1J0 Phone (905) 775-3783 Fax: (905) 775-4546 www.uoguelph.ca/muckcrop/ INDEX Page Index .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1-3 Staff .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Co-operators ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Seed Sources – 2010 ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Legend of Seed Sources ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction and Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. -

View / Open OURJ Spring 2018 Lelkins.Pdf

Oregon Undergraduate Research Journal 13.1 (2018) ISSN: 2160-617X (online) blogs.uoregon.edu/ourj Spitting Bars and Subverting Heteronormativity: An Analysis of Frank Ocean and Tyler, the Creator’s Departures from Heteronormativity, Traditional Concepts of Masculinity, and the Gender Binary Lizzy Elkins*, International Studies and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies ABSTRACT This paper seeks to investigate an emerging movement of rap and pop artists who actively subvert structures of the gender binary and heteronormativity through their music. The main artists considered in this research are pop/rap/R&B artist Frank Ocean and rap artist Tyler, the Creator, both of whom have claimed fame relatively recently. Artists like Ocean and Tyler make intentional departures from heteronormativity and the gender binary, combat concepts such as ‘toxic masculinity’, and hint at the possibilities for normalization and destigmatization of straying from the gender binary through lyrics, metaphysical expressions, physical embodiments of gender, expression of fluid/non-heteronormative sexualities, and disregard for labels in their sexual and gendered identities. I will discuss the history and context around music as an agent for social change and address privileging of the black heterosexual cisgender man as the central voice to pop/rap/R&B in the following research. This project will draw on Beauvoirian philosophy regarding gender as well as contemporary sources of media like Genius, record sale statistics, and album lyrics. By illustrating and evaluating how these artists subvert traditional concepts of gender and sexuality, I hope to also shine a light on how their music, which reaches millions of people who are less aware of or accepting of gayness, catalyzes social change and is significant in this current political moment, which is an era of increasing public tolerance of queer ideas and less binary gender expression. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2014 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 1 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre Johnson, Memphis Theological Seminary Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University Media & Print Manager: Travis Harris https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol1/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) . FO I ITH M I ,I T R T IDIE .ORT ~ PAru<.UN~V RSllY Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) 511<, a f't.dly volunteer 3raSS-roots or3an:za6on rooted :n h;,P ho,P and transf'orMat:ve j us6c.e, advocates f'or alternat:ves to, and the end d, the :nc..arc.eration of' al I youth . -

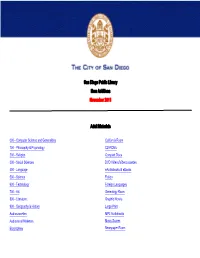

San Diego Public Library New Additions November 2011

San Diego Public Library New Additions November 2011 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes MP3 Audiobooks Audiovisual Materials Music Scores Biographies Newspaper Room Fiction Call # Author Title [MYST] FIC/BENISON Benison, C. C. Twelve drummers drumming : a mystery [MYST] FIC/BRADLEY Bradley, C. Alan I am half‐sick of shadows [MYST] FIC/CAMILLERI Camilleri, Andrea. The potter's field [MYST] FIC/CAMILLERI Camilleri, Andrea. The shape of water [MYST] FIC/CLARK Clark, Carol Higgins. Mobbed [MYST] FIC/CLEVERLY Cleverly, Barbara. Strange images of death : a Joe Sandilands murder mystery [MYST] FIC/CONNOLLY Connolly, John The burning soul : a thriller [MYST] FIC/CORBY Corby, Gary. The Ionia sanction [MYST] FIC/DOHERTY Doherty, P. C. The Templar magician [MYST] FIC/DOSS Doss, James D. Coffin man [MYST] FIC/DUNCAN Duncan, Elizabeth J. A killer's Christmas in Wales [MYST] FIC/EDWARDS Edwards, Yvvette. A cupboard full of coats [MYST] FIC/FIELDS Fields, Tricia. The territory [MYST] FIC/FINCH Finch, Charles (Charles B.) A burial at sea [MYST] FIC/GAVIN Gavin, Rick. Ranchero [MYST] FIC/GORMAN Gorman, Edward. Bad moon rising [MYST] FIC/GRABIEN Grabien, Deborah. Graceland [MYST] FIC/GRABIEN Grabien, Deborah. London calling [MYST] FIC/GRAFTON Grafton, Sue. V is for vengeance [MYST] FIC/HALL Hall, Patricia Dead beat [MYST] FIC/HEALD Heald, Tim. Death in the opening chapter [MYST] FIC/HECHTMAN Hechtman, Betty Behind the seams [MYST] FIC/HILLERMAN Hillerman, Tony. -

Sterbenz, Movement, Music, Feminism

Movement, Music, Feminism: An Analysis of Movement-Music Interactions and the Articulation of Masculinity in Tyler, the Creator’s ‘Yonkers’ Music Video Maeve Sterbenz NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: h+p:,,www.mtosmt.org,issues,mto.11.23.2,mto.01.23.2.sterben4.php 5EYWORDS: Movement, embodiment, feminist analysis, hip hop A9STRACT: Traditionally, explicit discussion of listeners’ bodies and personal experiences does not often appear in the realm of music analytical observations. One of the reasons for this omission is the masculinist bias that, prior to the 1990s, characteri4ed much of the field, and that tended to dismiss metaphorical language, overtly subjective musical descriptions, and the role of the body in musical practices all at once. A primary goal of feminist music theory has been to combat this bias by acknowledging many di>erent kinds of bodily experiences as vital to music analysis. In this paper, I suggest an analytical approach that examines interactions between human movement and music in detailed terms, in service of a feminist aim to take bodies seriously. Specifically, I aim to show how music-analytical a+ention can be productively directed towards the performing bodies that move to music in multimedia pieces by o>ering a close reading of a music video by the rapper Tyler, The Creator. My analysis focuses on the relationship between Tyler’s movement and the music and on this relationship’s role in informing ways that we might read his self-positioning and identity formation. In so doing, I hope to ?esh out a new feminist approach to analysis. -

Discovering the Theorist in Tupac: How to Engage Your Students with Popular Music

International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 2012, Volume 24, Number 2, 257-263 http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/ ISSN 1812-9129 Discovering the Theorist in Tupac: How to Engage Your Students with Popular Music Emily Lenning Fayetteville State University This paper introduces creative pedagogical techniques for exploring theory in the undergraduate classroom. Using criminal justice and criminological theories as a primary example, it describes a technique that professors from any theory-driven discipline can use to engage students through popular music, from hip-hop to musical theater in order to strengthen their grasp of the basic theoretical foundations of their field. By introducing music as a forum for understanding theory, we can both peak the interest of our students and demonstrate to them that theory is present in our everyday lives. Here we will consider the importance of integrating popular culture and technology in our classrooms, the ways pop music espouses the major assumptions of theory, and creative approaches we can use to make criminal justice, criminology, and other theory-driven disciplines even more exciting to our students. Like others, I have found that sociological theories Music as Cultural Influence in general, and criminological theories in particular, are some of the most difficult concepts for my students to Of course, even for criminal justice majors, most of grasp in a way that allows them to apply what they have their beliefs about crime and justice issues come from learned (e.g., Ahlkvist, 2001; Levy & Merestein, 2005). the media, which in and of itself speaks to the power of This is not because the material is particularly difficult mass communication. -

The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975 Directed by Göran Olsson

LeaderS: africaN americaN womeN SerieS THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE 1967–1975 DIRECTED BY gÖRAN oLSSoN educator guide engaging educators and students through film iN partNerShip with: TABLE OF CONTENTS aBout the fiLm p. 2 aBout the fiLmmaker p. 2 aBout the curricuLum writer p. 2 LessoN pLaN: aNgeLa DAViS, reVoLutioNarY poLiticS & radicaL CONNectioNS p. 3 pre-ScreeNiNg actiVitY p. 4 ViewiNg the moduLe p. 6 poSt-ScreeNiNg actiVity p. 7 aLigNmeNt to StaNdards p. 12 StudeNt haNdout a: film module Worksheet p. 13 StudeNt haNdout B: DOCUMENTARY PITCH p. 14 StudeNt haNdout c: DOCUMENTARY PITCH CHECKLIST p. 15 the film module and a Pdf of this lesson plan are available free online at itvs.org/educatorS/COLLectioNS ABOUT THE FILM The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 is a compilation of footage unearthed from the basement of a swedish television station that covers the evolution of the Black Power movement in the african american community and diaspora from 1967 to 1975. director and editor göran olsson lends an anthropological perspective to footage by overlaying contemporary audio interviews from leading african american artists, activists, musicians and scholars. ABOUT THE FILMMAKER gÖraN oLSSoN swedish born göran olsson attended stockholm university and the royal university of fine arts. a filmmaker, cinematographer and editor, he also developed the super-16 a-cam. he is the founder of the short documentary tV program Ikon (sVt) and is a member of the editorial board of ikon south africa. as editor of The Black Power Mixtape, he culled together hours of unreleased footage to reshape and retell the story of the civil rights. -

06/18 Vol. 5 Freestyle

06/18 Vol. 5 Freestyle memoirmixtapes.com Memoir Mixtapes Vol. 5: Freestyle June 15, 2018 Created by Samantha Lamph/Len Curated and edited by Samantha Lamph/Len and Kevin D. Woodall Visual identity design by J. S. Robson Cover stock photography courtesy of Vanessa Ives, publically available on Unsplash.com Special thanks to our reader, Benjamin Selesnick Letters from the Editors Welcome to Memoir Mixtapes Vol. 5: Freestyle. Hello again, everyone. (And “hey” to new readers!) Whether you’ve been reading MM since Vol.1, or this is your first time visiting our site, we’re so happy you’re This Volume is a little different from our usual here. publications. As Sam already mentioned, we hear “I have something I want to write for Memoir Mixtapes, Since we started Memoir Mixtapes, one of the most but it doesn’t fit the prompt!” pretty regularly. common questions we’ve been asked—volume after volume—came from readers who were eager to be a Like, a lot. part of the project. These potential contributors had a musically-inspired story to share, but it didn’t quite fit And so, after hearing those words enough we decided the current theme. We didn’t want to miss out on that we’d OPEN THE FUCKING PIT UP lol. those pieces, so this time around, we decided to put our themed issues on hold to give those writers their Our contributors, free of a prompt, were able to spread chance to bring those stories to the world. their wings wider this time, and the result is some truly unique work that, once again, I’m incredibly While it was quite a bit more challenging here on our proud to publish. -

Dancing Our Way to Freedom by Rabbi Rebecca Richman

Volume 28, Issue No. 4 Adar 5781 / March 2021 Dancing Our Way tO FreeDOm by Rabbi Rebecca Richman At the end of this month, we The Torah does not record any speech from the Israelites as they will begin our celebration cross. Moses’ outstretched arm and the Israelites’ ongoing of Passover. Our Passover march between the sea walls is the only choreography noted in preparations, the seder itself, and this moment of crossing. So, in the unwritten spaces, we the rituals we hold throughout imagine what the Israelites uttered and how they marched. Passover commemorate not only the Israelites’ departure For the past six months, I have been holding steady to a teaching from Egypt, but also their determination to dance their way from Rabbi Steven Nathan. In writing about the Israelites’ through the unknown. In our time, as we face our own abyss of crossing, he writes, “I wonder if they needed to sing while unknown, we have much to learn from the echoes of our crossing the Sea: not knowing if they would make it to the other ancestors’ hopeful song. side, but reaching for the strength within them to praise God while still not certain of what God had in store for them. Perhaps In parashat B’shalah, the Israelites come to face the Sea of their fear and their hope were too much to express in mere Reeds (also known as the Red Sea). The pillar of cloud that had words, and so they burst forth in song—perhaps first tenuously, led the way shifted to guard them from behind.