CONCEPT of PRAJNA and UPAYA • Bhajagovinda Ghosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

A General Recommended Way of Sitting Meditation by Dogen Zenji

UPAYA ZEN CENTER WINTER ANGO DOGEN READER ON SHIKANTAZA LED BY ROSHI JOAN HALIFAX EIHEI DOGEN “POINT OF ZAZEN” “A GENERAL RECOMMENDED WAY OF SITTING” “BENDOWA” “KING OF SAMADHIS” From: Kazuaki Tanahashi The Point of Zazen Yaoshan, Great Master Hongdao, was sitting. A monk asked him, “In steadfast sitting, what do you think?” Yaoshan said, “Think not thinking.” “How do you think not thinking?” Yaoshan replied, “Beyond thinking.” Realizing these words of Yaoshan, you should investigate and receive the authentic transmission of steadfast sitting. This is the thorough study of steadfast sitting transmitted in the buddha way. Yaoshan is not the only one who spoke of thinking in steadfast sitting. His words, however, were extraordinary. Think not thinking is the skin, flesh, bones, and marrow of thinking and the skin, flesh, bones, and marrow of not thinking. The monk said, How do you think not thinking? However ancient not thinking is, still we are asked how to think it. Is there not thinking in steadfast sitting? How can going beyond steadfast sitting not be understood? One who is not shallow and foolish can ask and think about steadfast sitting. Yaoshan said, Beyond thinking. The activity of beyond thinking is crystal clear. In order to think not thinking, beyond thinking is always used. In beyond thinking, there is somebody that sustains you. Even if it is you who are sitting steadfast, you are not only thinking but are upholding steadfast sitting. When sitting steadfast, how can steadfast sitting think steadfast sitting? Thus, sitting steadfast is not buddha thought, dharma thought, enlightenment thought, or realization thought. -

Literary History of Sanskrit Buddhism : from Winternitz, Sylvain Levi

LITERARY HISTORY OF Sanskrit Buddhism (From Winternitz, Syivain Levi, Huser) Ze G. K. NARIMAN ( Author of Religion of the Iranion Proples Sranian Influence on Muslim Literature ) Second Impremion. May 1923. Bombay: INDIAN BOOK DEPOT, 55, MEADOW STREET. FORT Linotyped and Printed by Mr. lhanythoy osabhoy at The Commercial Printing Press, (of The Tata Publicity Corporation, Limited,) 11, Cowasii Patell Strect, Fort, Jombay, and published by Indian Book lepot, 55, Meadow Street, Fort, Bonibay, LITERARY HISTORY OF SANSKRIT BUDDHISM (From Winternrrz, Syivain Tkevi, Huger) (Author of Religion of the Iranian Lranian May 1923. BOMBar: INDIAN BOOK DEPOT, G8, MEADOW STREET. FORT. OFFERED AS A TRIBUTE OF APPRECIATION TO Sir RABINDRANATH TAGORE THE POET SCHOLAR OF AWAKENING ORIENT. CONTENTS. FOREWORD, Paar, Introductory aes ‘sai aoe oe we CHAPTER I. ‘The two schools of Buddhism wee Essence of Mahayana... a eee «CHAPTER IL Sanskrit Buddhist canon oo ae on on . CHAPTER IIL. Mahavastu =... oe on ae oo on i Importance of Mahavastu ... ee tae so 18 Its Jatakas aes ove oe ove rE) Mabavastu and Puranas on on is More Mahayana affinities... one . 7 Antiquity of Mahavastu oo ae we on Ww CHAPTER Iv. Lalitavistara 4. oo oe o os 19 Extravagant imagery ... ae oo ae 20 Conception and Birth of Buddha... ase 20 Sin of unbelief - ne we oo te 22 Pali and Sanskrit. go back to an oldcr source 28 The Buddha at school aes oo 28 Acts of the Buddha ... oe oy 24 Component elements of Lalitavistara et Translation into Chinese and Tibetan “ee 25 Relation to Buddhist art ae - on 28 No image in primitve Buddhism ww 26 General estimate of Lalitavistara o “ 27 CHAPTER V. -

The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’S Mentality

International Conference of Electrical, Automation and Mechanical Engineering (EAME 2015) The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’s Mentality X.H. Li School of literature and Journalism Shandong University Jinan China Abstract—In order to study the influence of Buddhism, most of A. Sukhavati: Maitreya and MiTuo the temples and document in china were investigated. The results Hui Yuan and Daolin Zhi also have faith in Sukhavati. indicated that Buddhism developed rapidly in Southern dynasty. Sukhavati is the world where Buddha live. Since there are Along with the translation of Buddhist scriptures, there were lots many Buddha, there are also kinds of Sukhavati. In Southern of theories about Buddhism at that time. The most popular Dynasty the most prevalent is maitreya pure land and MiTuo Buddhist theories were Prajna, Sukhavati and Nirvana. All those theories have important influence on Nan dynasty’s literati, pure land. especially on their mentality. They were quite different from The advocacy of maitreya pure land is Daolin Zhi while literati of former dynasties: their attitude toward death, work Hui Yuan is the supporter of MiTuo pure land. Hui Yuan’s and nature are more broad-minded. All those factors are MiTuo pure land wins for its simple practice and beautiful displayed in their poems. story. According to < Amitabha Sutra>, Sukhavati is a perfect world with wonderful flowers and music, decorated by all Keyword-the evolvement of buddhism; southern dynasty; kinds of jewelry. And it is so easy for every one to enter this literati’s mentality paradise only by chanting Amitabha’s name for seven days[2] . -

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

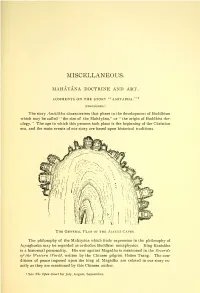

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

UPAYA BUDDHIST CHAPLAINCY TRAINING PROGRAM 2021 Information and Application

UPAYA BUDDHIST CHAPLAINCY TRAINING PROGRAM 2021 Information and Application Thank you for your interest in the Upaya Chaplaincy Training Program. Please read all the following information carefully to ensure that your application is complete and that you understand Upaya’s policies for this training program. APPLICATION PROCESS Spaces in this training program are limited; early application is advised. Applications are considered in the order they are received, up until one month before the start of the training program or until all places have been filled. Please know that not all applicants are accepted. This is a unique training program that requires a high level of commitment, and we strive to ensure that the training program is a good match for each applicant’s aspirations, experience, and goals. We prioritize applicants who have a strong background in Buddhist practice and who have studied with a Buddhist teacher. Note: If you have never been to Upaya before and never attended a retreat or workshop with Roshi Joan Halifax, we highly recommend that you consider registering for a Upaya retreat prior to applying for the program. Please visit our website, www.upaya.org, to see program offerings. If there are ethical or other concerns that arise during the application process or while enrolled in the program, Upaya Zen Center reserves the right to terminate a candidate’s participation in the Chaplaincy Training Program. If you have further questions about the training program or the application process, please contact the Program Coordinator, [email protected]. PROGRAM COST The total cost for the two-year program is $11,200, which is paid in two annual payments of $5,600 each (see below for payment and cancellation policies). -

Masi Kalpana: a Novel Dosage Form

Hussain Gazala : J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 2015; 4(3) Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation www.jpsionline.com Review Article MASI KALPANA: A NOVEL DOSAGE FORM Hussain Gazala* Associate Professor, Department of Rasashastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, SDM College of Ayurveda & Hospital, Hassan, Karnataka, India *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] DOI: 10.7897/2277-4572.04334 Received on: 15/04/15 Revised on: 08/05/15 Accepted on: 04/06/15 ABSTRACT Masi Kalpana is a therapeutic dosage form mentioned in Ayurveda Pharmaceutics. It is used for internal and external administration in various ailments. It is a medicinal form where plant and animal origin drugs are subjected to heat treatment by which it turns into a carbonized form useful in therapeutics. Its use in clinical practice is also elusive. A few research works have been carried in Pharmaceutical aspect but its therapeutic utility needs to be proved. Keywords: Masi, Pharmaceutics, Therapeutics, Carbonized form INTRODUCTION 3. Triphala Masi: Coarse powder of the drugs namely Haritaki (Terminalia chebula), Vibhitaki (Terminalia bellirica), Amalaki Masi Kalpana is a dosage form in Ayurveda Pharmaceutics where (Phyllanthus emblica) are taken and heated in an iron pan till it the drug is brought to a carbonized form by the process of turns black. It is used in Upadamsha vrana (soft chancre) with employing heat to the dry ingredients of drug. The drugs selected for madhu (Honey) for application. Masi preparation can be plant or animal origin. It is used for both internal and external use. Its usage is more as local application. Svaavida Masi4: The spines of porcupine, cut into small pieces 4. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism Keynote Papers of Sixth

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism Volume 6, Spring 2005 CONTENTS Introduction by the President Lewis R. Lancaster Editor's Note 2 Ananda W.P. Guruge IAB Honoree of the Year 2004 4 Countercurrents of Influence in East Asian Buddhism: Robert E. Buswell, Jr. The Korean Case Memorial to Dr. David Chappell 27 Ananda W.P. Guruge Proceedings of the Sixth International 28 Ananda W.P. Guruge Conference of Humanistic Buddhism KeynotePapers of SixthInternational Conference Lewis R. Lancaster 31 Buddhism and Culture James A. Santucci 40 Religion and Culture Benjamin Hubbard 55 Impact of Religion on Western Culture: A Mixed Legacy Ananda W.P. Guruge 67 Buddhism and Aesthetic Creativity J. Bruce Long 119 Jataka Tales and Ajanta Murals: 'Sacred Beauty' in Buddhist Words and Images Bhikkhu Pasadika 146 Inda-TibetanBuddhist Literature David Blundell 162 Language and Grammar of Sinhalese Aesthetics T. Dhammaratana 173 Buddhist Values and World Culture Baidyanath Labh 186 Buddhism and Cultural Adjustability in the Present World Scenario Padmal de Silva 197 Nature, Nurture and Mental Culture Richard L. Kimball 202 Buddhist Mental Culture and Western Psychology Ming Lee 219 Chinese Ch'an Buddhism and Mental Culture: Implications of the Sixth Patriarch's Platform Sutra on Counseling and Psychotherapy Otto H. Chang 229 Buddhism and Innovative Organizational Culture Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism Papers on Chinese Buddhist Culture of Sixth International Conference Dami Long 237 Understanding the Novel Xi-you-ji (Journey to the West) in the Context of Politics and Religions Wang Zhong Yao 257 The Flying Figure and Kwan-yin Bodhisattva in Dunhuang Caves Cheer Dean 269 Search for Description of the Mind: the Development of Alayavijiiiina in China Other papers on Related Subjects Ingrid Aall 282 Postmodern Buddhist Comodification: Pilgrimage and Tourism ChanjuMun 290 Wonhyo (617-686): A Critic of Sectarian Doctrinal Classifications Judith L. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Value in Tiantai Thought

SIX Value and Anti--value in Tiantai Thought The basic principles of Tiantai philosophy-the Three Truths, the mutual inherence of provisional and ultimate truth, omnicentric holism and inter subjectivity-provide important premises for Tiantai value theory, specifically the theory of value paradox. In this chapter, I first develop the value implica tions of these concepts and then discuss the texts in which Zhiyi and Zhanran explicitly treat the question of evil (Part I). Then, I consider the value theory in Zhili's version of the Tiantai tradition (Part II). This will prepare us to at tempt to apply this theory in a summary way to some concrete questions (in the Conclusion). PART I: GOOD AND EVIL IN ZHIYI AND ZHANRAN Value paradox can be derived from the basic Buddhist value of "non attachment." This ultimate value necessarily involves a value paradox since at tachment to "non-attachment," as any direct and non-paradoxical assertion of its value would entail, turns out to be an anti-value. The same can be said of attachment to the idea expressed in the previous sentence, and so on ad infi nitum. As the following discussion shows, the Tiantai tradition is very faithful to this early Buddhist notion, with non-attachment taking the form of an in tricate dialectic for overcoming all subtle forms of bias, a dialectic embodied in the Three Truths. This freedom from bias remains the ultimate value for Tiantai, but several other distinctive Tiantai notions combine to develop and Value and Anti-value in Tiantai Thought 241 intensify the value paradoxes inherent in this ultimate value.