Michael Richards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

197 F.3D 1284 United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. George

197 F.3d 1284 United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. George WENDT, an individual; John Ratzenberger, an individual, Plaintiffs- Appellants, v. HOST INTERNATIONAL, INC., a Delaware corporation, Defendant-Appellee, and Paramount Pictures, Corporation, a Delaware corporation, Defendant-Intervenor. No. 96-55243. Dec. 28, 1999. Before: FLETCHER and TROTT, Circuit Judges, and JENKINS, [FN1] District Judge. FN1. Honorable Bruce S. Jenkins, Senior United States District Judge for the District of Utah, sitting by designation. Order; Dissent by Judge KOZINSKI. Prior Report: 125 F.3d 806 ORDER The panel has voted to deny the petition for rehearing. Judge Trott voted to reject the petition for rehearing en banc and Judges B. Fletcher and Jenkins so recommend. The full court was advised of the petition for rehearing en banc. An active Judge requested a vote on whether to rehear the matter en banc. The matter failed to receive a majority of the votes in favor of en banc consideration. Fed. R.App. P. 35. The petition for rehearing is denied and the petition for rehearing en banc is rejected. *1285 KOZINSKI, Circuit Judge, with whom Judges KLEINFELD and TASHIMA join, dissenting from the order rejecting the suggestion for rehearing en banc: Robots again. In White v. Samsung Elecs. Am., Inc., 971 F.2d 1395, 1399 (9th Cir.1992), we held that the right of publicity extends not just to the name, likeness, voice and signature of a famous person, but to anything at all that evokes that person's identity. The plaintiff there was Vanna White, Wheel of Fortune letter-turner extraordinaire; the offending robot stood next to a letter board, decked out in a blonde wig, Vanna-style gown and garish jewelry. -

SHAY CUNLIFFE Costume Designer

(4/19/21) SHAY CUNLIFFE Costume Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES CAST “PEACEMAKER” James Gunn HBO Max John Cena (Series) The Safran Company Lochlyn Munro Warner Bros TV Robert Patrick “WESTWORLD” Jonathan Nolan HBO Evan Rachel Wood (Season 3) Amanda Marsalis, et al. Bad Robot Aaron Paul Winner: Costume Designers Guild (CDG) Award Thandie Newton Nomination: Emmy Award for Outstanding Fantasy/Sci-Fi Costumes “GONE BABY GONE” Phillip Noyce 20th Century Fox TV Peyton List (Pilot) Miramax Joseph Morgan “BOOK CLUB” Bill Holderman June Pictures Diane Keaton Jane Fonda Candice Bergen Mary Steenburgen “50 SHADES FREED” James Foley Universal Pictures Dakota Johnson Jamie Dornan “50 SHADES DARKER” James Foley Universal Pictures Dakota Johnson Jamie Dornan “A DOG’S PURPOSE” Lasse Hallström Amblin Entertainment Dennis Quaid Walden Media Britt Robertson Pariah “THE SECRET IN THEIR EYES” Billy Ray Gran Via Productions Nicole Kidman IM Global Julia Roberts Chiwetel Ejiofor “GET HARD” Etan Cohen Warner Brothers Will Ferrell Gary Sanchez Kevin Hart Alison Brie “SELF/LESS” Tarsem Singh Ram Bergman Prods. Ryan Reynolds Endgame Ent. Ben Kingsley “THE FIFTH ESTATE” Bill Condon DreamWorks Benedict Cumberbatch Participant Media Laura Linney “WE’RE THE MILLERS” Rawson Thurber New Line Cinema Jennifer Aniston Ed Helms Jason Sudeikis “THE BOURNE LEGACY” Tony Gilroy Universal Pictures Jeremy Renner Rachel Weisz Edward Norton “BIG MIRACLE” Ken Kwapis Universal Pictures Drew Barrymore Working Title Films John Krasinski Anonymous Content Kristen Bell “MONTE -

Donors' Report

Exeter College Donors’ Report 2012 EXETER COLLEGE DONORS’ REPORT | 12 EXETER COLLEGE DONORS’ REPORT | 12 From the Rector Our Annual Fund success owes much to to endow one of our History posts and It has been an astonishing year. Never before in the history the tireless work of Emily Watson (2003, an English post respectively. And a large of the College have so many of our Old Members made a Lit Hum), our Development Officer, and anonymous gift will help to endow the donation to the Annual Fund. And never has the College had the whole Development team, together cost of bursaries, which the College will with our students, who participated in support to help students from poor homes such a remarkable year of large gifts and pledges. three telethons last year (and loved the with the huge increase in tuition fees. reminiscences you shared with them). The Annual Fund raised £675,308 in Even more impressive than the overall Now we have to do even better in the It’s moving to see such affection and 2012, by far the largest amount it has ever sum is the number of alumni who coming year. After all, it would be great to support for the College, especially received and a staggering £145,000 more contributed. We are now the top College get from 29th into the World’s Top Ten, during tough economic times. We are than it raised last year. This will help us in Oxford in terms of participation with and if anyone can do it, it’s Exonians. -

Jason Alexander Set to Guest Star in Tv Land's New Sitcom “Kirstie” Alongside Series Regular and Fellow “Seinfeld” Alum Michael Richards

JASON ALEXANDER SET TO GUEST STAR IN TV LAND'S NEW SITCOM “KIRSTIE” ALONGSIDE SERIES REGULAR AND FELLOW “SEINFELD” ALUM MICHAEL RICHARDS New York, NY – June 13, 2013 – Jason Alexander has officially moved on from Vandalay Industries – now he’s got a new job as Broadway star Maddie Banks’ (Kirstie Alley) agent in TV Land’s new sitcom “Kirstie” in a guest starring role. Set to shoot later this month, the show reunites Alexander with his former “Seinfeld” co-star Michael Richards who plays Alley’s eccentric driver in the new comedy. Alexander shared, "It is a strange and wonderful thing to be working on a brand new show yet surrounded by familiar faces and friends. I'm looking forward to a fun and fabulous time." The show centers around Broadway star Madison Banks (Kirstie Alley) whose life turns upside down when Arlo (Eric Petersen), the son she gave up at birth, suddenly appears, hoping to connect after his adoptive parents have died. Rhea Perlman (“Cheers”) stars as Maddie’s assistant and best friend alongside Richards (“Seinfeld”) as Maddie’s outlandish driver. “Kirstie” is written and executive produced by Marco Pennette and is also executive produced by Kirstie Alley and Jason Weinberg. Larry W. Jones and Keith Cox serve as executive producers for TV Land. Please log onto www.tvlandpress.com for up-to-the-minute information, press releases and photos. About TV Land TV Land is the programming destination featuring the best in entertainment on all platforms for consumers in their 40s and 50s. Consisting of original programming, classic and contemporary television series acquisitions, hit movies and a full-service Web site, TV Land is now seen in over 98 million U.S. -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

On Richards, Race, and Empathy

Lanita Jacobs, Ph.D. Word Count: 5318 Anthropology Department University of Southern California 3601 Watt Way, GFS 120 Los Angeles, CA 90089-1692 Office: (213) 740-1909 Email: [email protected] On Richards, Race, and Empathy It has been well over a month since Richards blasted four Black males at the Laugh Factory, one of several clubs I frequent in my research on Black comedy. To be frank, I care less about Richards’ words, the news coverage, and the televised apologies. I sit, poised to write, and find myself in a weary place. Actually, I am weary of race … of what happens when a white man of notoriety goes off about “niggers” and makes a veiled reference to lynching. “So what?” as comic Chris Spencer told me wearily, “Not all white people think that way.” Lest you think I want to engage in one of the safest possible ways of discussing race, let me tell you why I am weary. It is safe to say that Richards lost it. Onstage. And somebody recorded it with their cell phone. And that is, in large part, why you and I are even having this conversation. Having watched comics closely over the past five years, I can appreciate (though not excuse) his tirade as indicative of what happens when a comic’s stage time is threatened. Comics work hard to perform in Los Angeles. The self-described “world-renown” Laugh Factory can rightly boast its title. It’s a great place for a comic to play and those who grace its stage often have to endure the careful scrutiny of club owner and former-comic Jamie Masada. -

Tv Land Greenlights Original Sitcom “Kirstie’S New Show” Starring Kirstie Alley

TV LAND GREENLIGHTS ORIGINAL SITCOM “KIRSTIE’S NEW SHOW” STARRING KIRSTIE ALLEY Rhea Perlman, Michael Richards And Eric Petersen Also Star In Series Premiering Fall 2013 New York, NY – February 15, 2013 – Multiple Emmy® Award-winner Kirstie Alley is lighting up the stage on TV Land as the network picks up “Kirstie’s New Show,” a new sitcom revolving around Alley as Broadway star Madison Banks. The sitcom reunites the actress with longtime friend and former “Cheers” co-star Rhea Perlman and pairs them with famed “Seinfeld” actor Michael Richards, both of whom have won multiple Emmy® Awards as well. “Kirstie’s New Show” also stars Eric Petersen (“Shrek: The Musical”) and will premiere in Fall 2013 with 12 episodes. Alley took to Twitter today to announce the series and celebrate the good news (see her video announcement here). “This cast is a TV Land dream team of stars. Seeing them all together is truly mind-blowing,” said TV Land President Larry W. Jones. “This series pick-up reaffirms our commitment to making broadcast quality original programming for a network whose brand stands for timeless entertainment.” “We’ve been after Kirstie for two years, and now we found the perfect show for her and the perfect writer in Marco Pennette,” added Keith Cox, Executive Vice President, Development and Original Programming. “We are so excited to give a home to Kirstie and this amazing cast with a show that TV Land fans will love.” -more- Page 2 – TV Land Greenlights Original Sitcom “Kirstie’s New Show” Starring Kirstie Alley “Kirstie’s New Show” revolves around Madison “Maddie” Banks, a renowned Broadway star who finds her life turned upside down when Arlo (Petersen), the son she gave up at birth, suddenly appears hoping to connect after his adoptive parents have died. -

Viacom Acquires Exclusive Cable Rights to Seinfeld from Sony Pictures Television

Hello, Jerry! Viacom Acquires Exclusive Cable Rights to Seinfeld From Sony Pictures Television September 22, 2019 Viacom’s Entertainment Brands to Begin Airing Seinfeld in 2021 ... Yada Yada Yada ... Select Episodes Will Also be Available to Stream on Authenticated Viacom Websites and Apps NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 21, 2019-- Viacom (NASDAQ: VIAB, VIA) today announced the acquisition of Seinfeld from Sony Pictures Television, in a deal that features the exclusive cable rights for all 180 episodes of the iconic series. Beginning in October 2021, the full library of Seinfeld episodes will air amongst Viacom’s entertainment brands, including Comedy Central, Paramount Network and TV Land. Additionally, catch-up episodes will be available through Viacom brands via authenticated video on demand, websites and apps. The deal was closed by Barbara Zaneri, EVP, Viacom Global Program Acquisitions, and Flory Bramnick, EVP, US Distribution, for an undisclosed sum and a loaf of marble rye after a spirited Festivus feats of strength competition. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190921005015/en/ “We’re extremely proud to bring this little-known series to our viewers. With the right programming and promotion, we believe we’ll finally get Seinfeld the recognition it truly deserves, as merely the greatest sitcom of all-time,” said Kent Alterman, President of Comedy Central, Paramount Network, TV Land and Vandelay Industries. John Weiser, President, First Run Television for Sony Pictures Television said, “Seinfeld airing on Comedy Central and the Viacom networks brings together the greatest comedy of all time, with the best brands in cable. -

The Opposite Free

FREE THE OPPOSITE PDF Tom MacRae,Elena Odriozola | 24 pages | 30 Sep 2006 | Peachtree Publishers | 9781561453719 | English | United States Opposite Synonyms, Opposite Antonyms | These example sentences are selected automatically from various online news sources to reflect current usage of the word 'opposite. Send us feedback. See more words from the same century Dictionary Entries The Opposite opposite opposed opposeless opposing train opposite opposite lady opposite-leaved opposite number. Accessed 21 Oct. Keep scrolling for more More Definitions for opposite opposite. Entry 1 of 4 : located at the other end, side, or corner The Opposite something : located across from something : completely different opposite. Entry 1 of 4 1 : being at the other end, side, or corner We live on opposite sides of the street. Keep scrolling for more More from Merriam- Webster on opposite Thesaurus: All The Opposite and antonyms for opposite Nglish: Translation of opposite for Spanish Speakers Britannica English: Translation of opposite for Arabic Speakers Comments on opposite What made you want to look up opposite? Please tell us where you read or heard it including the quote, if possible. Test Your Knowledge - and learn some interesting things along the way. Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free! You can never have too much storage. What Does 'Eighty-Six' Mean? We're intent on clearing it up 'Nip it in the butt' or 'Nip it in the bud'? We're gonna The Opposite you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe Is Singular 'They' a Better Choice? Name that government! Or something like that. -

Falange, Autarky and Crisis: the Barcelona General Strike of 1951

Articles 29/4 1/9/99 3:27 pm Page 543 Michael Richards Falange, Autarky and Crisis: The Barcelona General Strike of 1951 ‘Salta la liebre donde menos se piensa’1 Barcelona, in February and March 1951, saw the most signifi- cant wave of popular protest since the heyday of the city’s revolu- tion during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939. Thousands of people from various social groups and of diverse political back- grounds or affiliation united in an escalating three-week series of protests against the exploitation and violence that had been imposed for eleven years by the Franco dictatorship. Initiated by a boycott of the city tram system, the movement culminated in a general strike in which some 300,000 workers took part, paralysing the city and shutting down production in the industrial centres.2 Within months of the Barcelona protests further strikes took place, both again in Barcelona and in other regions of Spain, principally, the urban centres. These events provide a glimpse of pent-up frustrations and suppressed identities under the dictator- ship: class consciousness, progressive Catalanism, civic soli- darity.3 Not until the mass demonstrations of 1976 which heralded the arrival of democracy in Spain, after forty years of Francoism, would popular unrest reach the level of 1951.4 It is unlikely that Franco’s regime was put in real danger. The massive apparatus of armed public control, which was, for reasons explored in this article, only briefly glimpsed in 1951, could not be more than inconvenienced by such a protest.5 Moreover, Francoism’s militant anti-communism meant that the regime was becoming a significant asset in the West’s Cold War struggle against the Soviet bloc, and was therefore supported and maintained particularly by the United States government.6 European History Quarterly Copyright © 1999 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Program Guide Report

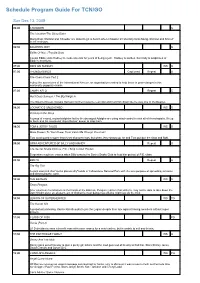

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Dec 13, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Vacation/The Sleep Eater Mung Daal, Shnitzel and Chowder are about to go to beach when Chowder accidentally locks Mung, Shnitzel and himself in the restroom. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G Eddie Or Not.../Trouble Date Cousin Eddie visits Rodney to make amends for years of being a jerk. Rodney is smitten, but Andy is suspicious of Eddie's intentions. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G The Cham Cham Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Hard Days Samson / The Big Weigh In The Squirrel Scouts mistake Samson for their favourite teen idol and hunt him down like he was one of the Beatles. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G A Creep in the Deep A group of crazed, mutant dolphins led by the deranged Adolpho are using mind-control to sink all of Acmetropolis. It's up to Duck and his newfound "Aqua Dense" power to stop them. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G More Powers To You/ Power Tom/ Catch Me Though You Can't Tom must guard a super team's set of power rings, but when Jerry shows up, he and Tom put don the rings and fight. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G The Secret Snake Club vs. P.E. / King Tooten Pooten Serpentine mayhem ensues when Billy turns to the Secret Snake Club to help him get out of P.E.