Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER JANAZAH: an Investigation Into Violence, Homicide and Somali-Canadian Youth in Ontario

ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER JANAZAH: An Investigation into Violence, Homicide and Somali-Canadian Youth in Ontario April 25th, 2018 Dedicated to the memory of: Ali Mohamud Ali Son, brother and friend. Contents Preface . 2 About Youth LEAPS . 3 Acknowledgements . 3 Executive Summary . 4 Introduction: The Somali Youth Research Initiative . 6 Methodology: Collecting and Analyzing Data on Somali Youth Homicides . 8 Demographic Data Collection . 9 Literature Review . 9 Focus Group Discussions . 9 Survey . 10 JANAZAH: ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER The Homicide Data Base . 11 Limitations . 12 Demographic Profile: Legacy of Precarity . 14 Literature Review: Mapping Out Youth Violence . 17 Key Findings . 20 Toronto Homicide Victims . 20 Homicide Victim Profile . 23 Personal belonging and Connection to violence . 26 in Ontario Youth Homicide and Somali-Canadian Violence, into An Investigation Call to Action: Sharpening the Focus . 30 Recommendations . 32 References . 34 Tables . 36 Table 1 . Homicide Incidence Rate (annual)-Toronto . 36 Table 2 . Disproportionality index-Somali Homicides in Toronto . 37 Table 3 . Homicide Database N=40 (Toronto) . 37 Table 4: Perception of safety post-violent crime . 38 Table 5: Perceptions and Experiences of Violence Among Somali youth in Ontario . 39 Table 6: Somali community leadership impact on violence prevention . 40 Table 7: Institutional impact on homicide reduction (ranked) . 40 Table 8: Stakeholder responsibility in reducing youth violence (ranked) . 40 Table 9: Prioritizing youth community engagement (ranked) . 41 Table 10: Community level of responsibility around violence prevention and reduction . 41 Table 11 . Socio-demographic characteristics of participants citing ‘homicides’ in experiences of violence . 42 Preface Phone rings. Liban: Hey, what’s up? How are you? Friend: Not much . -

Thesis Draft

! ! ! ! ! The Mobile Citizen: Canada’s Treatment of Mobility in Immigration, Citizenship, and Foreign Policy ! Alex M. Johnston ! ! Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science ! ! School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Science University of Ottawa ! ! © Alex M. Johnston, Ottawa, Canada, 2017. The Mobile Citizen ii Abstract ! Mobility, as the ability among newcomers and citizens to move temporarily and circularly across international borders and between states, has become a pervasive norm for a significant portion of Canada’s population. Despite its pervasive nature and the growing public interest, however, current research has been limited in how Canadian policies are reacting to the ability of citizens and newcomers to move. This thesis seeks to fill that gap by analyzing Canada’s treatment of mobility within and across policies of immigration, citizenship and foreign affairs. An analytical mobility framework is developed to incorporate interdisciplinary work on human migration and these policy domains. Using this framework, an examination of policy developments in each domain in the last decade reveals that they diverge in isolation and from a whole-of-government perspective around the treatment of mobility. In some instances policy accommodates or even embraces mobility, and in others it restricts it. The Mobile Citizen iii Table of Contents Abstract i Table of Contents and List of Table and Figures ii Introduction -

Rethinking the Canadian Diaspora by Kenny Zhang* Executive Summary

September 2007 www.asiapacifi c.ca Number 46 “Mission Invisible” – Rethinking the Canadian Diaspora By Kenny Zhang* Executive Summary The evacuation of tens of thousands of Canadians Th e size of the Canadian diaspora is remarkable from Lebanon in 2006, a pending review of dual relative to the resident national population, even when citizenship and a formal diplomatic protest to compared with other countries that are well-known China over the jailing of a Canadian citizen for for their widely dispersed overseas communities. Th e alleged terrorist activities are examples of the new survey shows that the Canadian diaspora does complex and extensive range of policy issues raised not exist as scattered individuals, but as an interactive by the growing number of Canadian citizens living community with various organizations associated abroad. It has also shown the need for Canada to with Canada. Th e study also suggests that living think strategically about the issue of the Canadian abroad does not make the Canadian diaspora less diaspora, rather than deal with the problems raised “Canadian,” although it is a heterogeneous group. Th e on a case-by-case basis. majority of overseas Canadians still call Canada home and have a desire to return to Canada. Many keep An earlier report (Commentary No. 41) by the close ties with the country by working for a Canadian Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) entity and visiting families, friends, business clients or discussed the concept of the Canadian diaspora partners, and various other counterparts in Canada. and estimated the size of this community at 2.7 million. -

CIC Diversity Colume 6:2 Spring 2008

VOLUME 6:2 SPRING 2008 Guest Editor The Experiences of Audrey Kobayashi, Second Generation Queen’s University Canadians Support was also provided by the Multiculturalism and Human Rights Program at Canadian Heritage. Spring / printemps 2008 Vol. 6, No. 2 3 INTRODUCTION 69 Perceived Discrimination by Children of A Research and Policy Agenda for Immigrant Parents: Responses and Resiliency Second Generation Canadians N. Arthur, A. Chaves, D. Este, J. Frideres and N. Hrycak Audrey Kobayashi 75 Imagining Canada, Negotiating Belonging: 7 Who Is the Second Generation? Understanding the Experiences of Racism of A Description of their Ethnic Origins Second Generation Canadians of Colour and Visible Minority Composition by Age Meghan Brooks Lorna Jantzen 79 Parents and Teens in Immigrant Families: 13 Divergent Pathways to Mobility and Assimilation Cultural Influences and Material Pressures in the New Second Generation Vappu Tyyskä Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee 84 Visualizing Canada, Identity and Belonging 17 The Second Generation in Europe among Second Generation Youth in Winnipeg Maurice Crul Lori Wilkinson 20 Variations in Socioeconomic Outcomes of Second Generation Young Adults 87 Second Generation Youth in Toronto Are Monica Boyd We All Multicultural? Mehrunnisa Ali 25 The Rise of the Unmeltable Canadians? Ethnic and National Belonging in Canada’s 90 On the Edges of the Mosaic Second Generation Michele Byers and Evangelia Tastsoglou Jack Jedwab 94 Friendship as Respect among Second 35 Bridging the Common Divide: The Importance Generation Youth of Both “Cohesion” and “Inclusion” Yvonne Hébert and Ernie Alama Mark McDonald and Carsten Quell 99 The Experience of the Second Generation of 39 Defining the “Best” Analytical Framework Haitian Origin in Quebec for Immigrant Families in Canada Maryse Potvin Anupriya Sethi 104 Creating a Genuine Islam: Second Generation 42 Who Lives at Home? Ethnic Variations among Muslims Growing Up in Canada Second Generation Young Adults Rubina Ramji Monica Boyd and Stella Y. -

Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-5-2012 12:00 AM Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present Melissa Stachel The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Randa Farah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Melissa Stachel 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Stachel, Melissa, "Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 983. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/983 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOMALI CHILDREN AND YOUTH’S EXPERIENCES IN EDUCATIONAL SPACES IN NORTH AMERICA: RECONSTRUCTING IDENTITIES AND NEGOTIATING THE PAST IN THE PRESENT (Spine title: Somali Children and Youth’s Experiences in North America) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Melissa Stachel Graduate Program in Anthropology Collaborative Program in Migration and Ethnic Relations A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Melissa Stachel 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-Operative Sector

International Journal of CO-OPERATIVE ACCOUNTING AND MANAGEMENT, 2020 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 DOI: 10.36830/IJCAM.202014 Locating the Contributions of the African Diaspora in the Canadian Co-operative Sector Caroline Shenaz Hossein, Associate Professor of Business & Society, York University, Canada Abstract: Despite Canada’s legacy of co-operativism, Eurocentrism dominates thinking in the Canadian co- op movement. This has resulted in the exclusion of racialized Canadians. Building on Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s (2014) exposure of the historical fact of African Americans’ alienation from their own cooperativism as well as the mainstream coop movement, I argue that Canadian co-operative studies are limited in their scope and fail to include the contributions of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC). I also argue that the discourses of the Anglo and Francophone experiences dominate the literature, with mainly white people narrating the Indigenous experience. Finally, I hold that the definition of co-operatives that we use in Canada should include informal as well as formal co-operatives. Guyanese economist C.Y. Thomas’ (1974) work has influenced how Canadians engage in co-operative community economies. However, the preoccupation with formally registered co-operatives excludes many BIPOC Canadians. By only recounting stories about how Black people have failed to make co-operatives “successful” financially, the Canadian Movement has missed many stories of informal co-operatives that have been effective in what they set out to do. Expanding what we mean by co-operatives for the Canadian context will better capture the impact of co-operatives among BIPOC Canadians. Caroline Shenaz Hossein is Associate Professor of Business & Society in the Department of Social Science at York University in Toronto, Canada. -

Culture, Context and Mental Health of Somali Refugees

Culture, context and mental health of Somali refugees A primer for staff working in mental health and psychosocial support programmes I © UNHCR, 2016. All rights reserved Reproduction and dissemination for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, or translation for any purpose, is prohibited without the written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Public Health Section of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) at [email protected] This document is commissioned by UNHCR and posted on the UNHCR website. However, the views expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of UNHCR or other institutions that the authors serve. The editors and authors have taken all reasonable precautions to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees be liable for damages arising from its use. Suggested citation: Cavallera, V, Reggi, M., Abdi, S., Jinnah, Z., Kivelenge, J., Warsame, A.M., Yusuf, A.M., Ventevogel, P. (2016). Culture, context and mental health of Somali refugees: a primer for staff working in mental health and psychosocial support programmes. Geneva, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Cover photo: Dollo Ado, South East Ethiopia / Refugees are waiting for non-food items like plastic sheets and jerry cans. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

Citizenship RevoCation in the MainstReaM pRess: a Case of Re-ethni- Cization? elke WinteR ivana pRevisiC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-5-2012 12:00 AM Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present Melissa Stachel The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Randa Farah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Melissa Stachel 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Stachel, Melissa, "Somali Children and Youth's Experiences in Educational Spaces in North America: Reconstructing Identities and Negotiating the Past in the Present" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 983. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/983 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOMALI CHILDREN AND YOUTH’S EXPERIENCES IN EDUCATIONAL SPACES IN NORTH AMERICA: RECONSTRUCTING IDENTITIES AND NEGOTIATING THE PAST IN THE PRESENT (Spine title: Somali Children and Youth’s Experiences in North America) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Melissa Stachel Graduate Program in Anthropology Collaborative Program in Migration and Ethnic Relations A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Melissa Stachel 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

Somali Parents' Beliefs and Strategies for Raising Bilingual Children

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 6-2018 Somali-English Bilingualism: Somali Parents’ Beliefs and Strategies for Raising Bilingual Children Abdirahman Ikar St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Ikar, Abdirahman, "Somali-English Bilingualism: Somali Parents’ Beliefs and Strategies for Raising Bilingual Children" (2018). Culminating Projects in English. 137. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/137 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Somali-English Bilingualism: Somali Parents’ Beliefs and Strategies for Raising Bilingual Children by Abdirahman Ikar A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts in English: Teaching English as a Second Language June, 2018 Thesis Committee: James Robinson, Chairperson Choonkyong Kim Rami Amiri 2 Abstract The American Midwest is home to a large number of refugees from Somalia. Numerous studies have explored immigrant communities’ beliefs and strategies for bilingual development of their children. However, there has only been one study (Abikar, 2013) that explored this topic from the perspective of Somali parents. The aim of this qualitative study was to look at first- generation Somali parents’ beliefs and strategies for bilingual development of their children. 10 first-generation Somali parents were interviewed using semi-structured interview questions. -

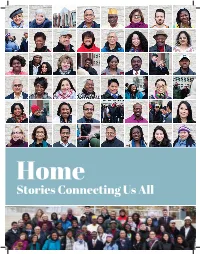

Stories Connecting Us All

Home Stories Connecting Us All Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 1 Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 2 Home Stories Connecting Us All Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 3 Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 4 Home Stories Connecting Us All Edited by Tololwa M. Mollel Assisted by Scott Sabo Book design and cover photography by Stephanie Simpson Edmonton, Alberta Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 5 © 2017 Authors All rights reserved. No work in this book can be reproduced without written permission from the respective author. ISBN: in process Home: Stories Connecting Us All | 6 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................13 ASSIST Community Services Centre: Bridging People & Communities ...............45 Letter from the Prime Minister ..................17 by the Board and Staff of ASSIST Community Services Centre War and Peace ...................................................19 To the Far North .............................................. 48 by Hussein Abdulahi by Nathaniel Bimba The International and Heritage Embracing Our Differences ..........................51 Languages Association’s Contributions to by Mila Bongco-Philipzig Multiculturalism and Multilingualism- 40 Years of Service .................................................22 Lado Luala ...........................................................54 by Trudie Aberdeen, PhD by Barizomdu Elect Lebe Boogbaa Finding a Job in Alberta .................................25 My Amazing Race ............................................ 56 by A.E.M. -

The Somali Diaspora in Greater Boston

Trotter Review Volume 22 Article 6 Issue 1 Appreciating Difference 7-21-2014 The omS ali Diaspora in Greater Boston Paul R. Camacho University of Massachusetts Boston Abdi Dirshe Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Federal Government of Somalia Mohamoud Hiray National Grid Mohamed J. Farah Bunker Hill Community College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review Part of the African American Studies Commons, African Studies Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Camacho, Paul R.; Dirshe, Abdi; Hiray, Mohamoud; and Farah, Mohamed J. (2014) "The omS ali Diaspora in Greater Boston," Trotter Review: Vol. 22: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol22/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trotter Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TROTTER REVIEW The Somali Diaspora in Greater Boston Paul R. Camacho, Abdi Dirshe, Mohamoud Hiray, and Mohamed J. Farah East Africans as America’s Newest Immigrants Our nation was founded on and thrives on immigration. One of the newest immigrant groups in the Boston area are Somalis. They are among the largest of the new populations of African immigrants. While precise numbers are very difficult to determine, there are approximately 8,000 in the Greater Boston area and another 2,000 estimated across the rest of Massachusetts. Very few studies have examined Somalis in the United States, and no studies exist on the community in Boston or Massachusetts.